This week, we’re switching gears at The Brainfluence Podcast… no guest, just me (Roger)… What we’re going to do is talk about The Persuasion Slide™ model.

I first presented it at last year’s Conversion SUMMIT in Frankfurt, Germany – an amazing conference run by conversion expert Andre Morys. (The speaker lineup was amazing, I felt privileged to be included in that group of really savvy experts.)

As you know, or will figure out if you read my writing, I focus a lot on non-conscious effects on the behavior of consumers and web visitors. But, there are a lot of those effects!

Robert Cialdini introduced his six principles of persuasion, but there are many other factors that don’t fit neatly into those categories. Sensory factors, the weird way our brains process numbers, and many, many other factors all play a role.

In addition, conscious factors like features, benefits, and price are usually a key part of any decision process. And, of course, there’s the minefield of customer/user experience.

In addition, conscious factors like features, benefits, and price are usually a key part of any decision process. And, of course, there’s the minefield of customer/user experience.

I wanted to integrate these areas and more into a practical and actionable business model.

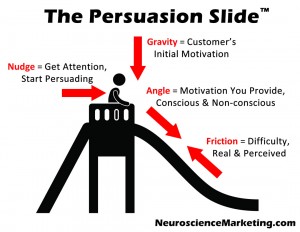

The Persuasion Slide is a framework for understanding persuasion, using the analogy of a playground staple – the slide. Think of it not as a theory in itself, but as a container into which theories fit.

I expect to revert to our normal guest interview format next week, but please let me know what you think of this episode in a comment below, in particular whether you loved it or hated it. (If you hated it, don’t worry – I don’t expect this to happen often.)

If you enjoyed it, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast, and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to understand The Persuasion Slide model.

- Why no single theory of persuasion or motivation completely explains behavior.

- Conscious Motivation vs Non-conscious Motivation.

- How to reduce the effect of the two components of friction on your slide.

- How you can save HUGE amounts of money by focusing on non-conscious factors!

Key Resources:

Introduction to The Persuasion Slide (article)

Amazon: Webs of Influence: The Psychology of Online Persuasion

by Nathalie Nahai

Amazon: Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini

Amazon: The Psychology of Price: How to use price to increase demand, profit and customer satisfaction by Leigh Caldwell

Amazon: Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions by Dan Ariely

Amazon: Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Amazon: Brainfluence: 100 Ways to Persuade and Convince Consumers with Neuromarketing

Amazon Kindle Edition: Brainfluence: 100 Ways to Persuade and Convince Consumers with Neuromarketing

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: This is the Brainfluence Podcast and I am Roger Dooley. This week we’re going to change things up a bit. So far in the Brainfluence podcast, we’ve had quite a few great guests. We started off with Nathalie Nahai, the web psychologist, and most recently had Chris Brogan and John Jantsch. This week, we’re going to do things a little bit differently. We’re not going to have a guest. You’re going to be stuck with me, just me, and I’m going to talk about the Persuasion Slide.

This is a model for persuasion that I first debuted at the ConversionSUMMIT with my friend Andre Morris in Frankfurt, Germany last year. After the conference, I wrote a blog post about it, which has been one of my most viewed and shared posts in a long time. What I thought I would do is try and paint a word picture of that for my audio listeners.

It is a visual topic, so if you are near a computer or have access to some kind of a screen, I encourage you to check out the show notes at RogerDooley.com or just Google “The Persuasion Slide” and you should find both, a picture and illustration of it as well as my blog post about it. If not, don’t worry. I think even an audio only we’ll be able to do just a fine job of presenting it.

The first thing that I want to talk about is that it is not a theory of persuasion such as those that might be created by academics. It’s not a mechanism for persuasion either, but the Persuasion Slide is a model. It’s a container into which other theories can fit. The origin of it was I was looking for a way to integrate different theories of persuasion into a practical business model. There are all kinds of theories out there.

Bob Cialdini has this famous Six Principles that you’ve all heard of, things like social proof and reciprocity. Stanford’s BJ Fogg has his Behavior Model that’s a pseudo-equation that explains how and when persuasion can occur. Totally different approach comes from evolutionary psychologists like Jeffrey Miller who believed that much of our behavior, including purchasing behavior, is driven by those same programs that were coded 50,000 or more years ago in our hunter/gatherer days.

Then there’s still other theorists like Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize winner who has this System 1, System 2 thinking and focuses on the fact that people will almost always choose the fast, intuitive, emotional approach to decision making when they can and will only resort to actual logical, rational analysis if they’re forced to. Then there are all kinds of ad hoc findings from behavior scientists. People like Dan Ariely, Adam Alter, and many others are finding really interesting insights into human behavior that in many cases can be applied to the persuasion and the conversion process.

The objective is to put these and other elements, including things that are perhaps not psychological, but more practical things like price, features, benefits, user experience, and put this all into one model that makes sense and that can be used to analyze any given business persuasion situation. With that said, let’s talk a little bit about the Persuasion Slide.

It’s based on the common playground apparatus, the children’s slide. We’ve all seen that. If there are any physicists among our listeners, they would call that an inclined plane. An inclined plane is a sloped surface and you place a block on it and the block will tend to slide down the plane. Its motion is driven by gravity, of course.

The other key factor on whether that block will slide and how fast it slides is the angle of the plane. You could imagine if the angle of the slide is very flat. Someone will get on it and nothing would happen. If the angle is steep enough though, of course, the slide works. The block slides down the plane. The enemy, as physicists would say, of that sliding motion is friction.

Friction is a force that operates in direct opposition to gravity on an inclined plane and it pushes back against the force of gravity. If there’s enough friction, of course, the sliding effect doesn’t happen. You’ve probably all seen a young child slide in the playground and get about halfway down and get stuck because the slide is rusty or poorly maintained. That’s the effect of friction.

The final piece isn’t necessarily a part of most physicist’s model of an inclined plane, but that’s the nudge. That’s if you’ve seen a little kid get up on a slide at the top, often they need a nudge from mom or dad, or if mom or dad isn’t there, they’ll use their arms to propel them self off of the horizontal ledge and into the sloped part of the slide to get going. What we want to do here today is talk a little bit about the science of persuasion and how that is integrated.

Now, I mentioned we have Robert Cialdini’s six factors. These are things like social proof, in which if you see somebody else doing something or many people doing it, you’re more likely to be persuaded to do it yourself. It’s the old trucks outside the diner thing. Reciprocity; if I do something for you, you are more likely to do something for me in return. These other factors are authority, liking, commitment and consistency, and scarcity. These are the basics of persuasion psychology, and are perhaps not the only factors, but certainly explain an awful lot of the persuasion process.

As I also mentioned, we’ve got people like Fogg, with his Behavior Model, Jeffrey Miller in evolutionary psychology. The one area that I didn’t mention is that today we’ve got some really interesting findings coming out of brain imaging. Today, scientists can put subjects in fMRI machine and actually see in real time what’s going on inside their brain as they’re presented with information, and even as they’re making decisions.

The point is that no single theory completely explains all behavior. You can’t just say, “I’ve got Cialdini’s Six Principles, I’m done.” Or “I’ve really got Fogg’s Behavior Model.” I think that as business people, we need to integrate those concepts and many others and use them as appropriate for our particular persuasion situation, which could be very different. If we’re in an in-person sales process, if we’re looking at web conversion on a lead generation site, you may find that very different approaches are required.

Let’s look at first at the force of gravity on that slide. In our model, gravity represents the customer. I’m going to say customer even though perhaps it could be a lead prospect or something else. It’s their initial motivation; their needs, their wants, their goals. That’s what they’re coming to you with, not what you are giving them. That’s their starting point.

When you try and persuade people by saying, “Do this for me” or “Do this,” you are fighting gravity. What you want to do is work with gravity. Show how you can help them achieve their goals, meet their needs, and so on. That will make you far more successful. If you look at a typical, say, newsletter sign-up process on a website, you’ve got some folks who have messages like “Sign Up Now.” That is working against gravity.

On the other hand, if you look at sites that perhaps are offering information on how to make money, they will often say, “Click here” or “Put your email address here to learn how to make a thousand dollars a month or $5,000 a month,” or whatever they’re promising. What they’re doing is they’re aligning their call to action with gravity.

Now, we talked about the nudge at the top of the slide. In our model, that represents a couple of things. First, it’s getting the attention of the prospect or the visitor. You have to; before you can even begin the persuasion process, have their attention focused on you. That nudge could be an email. It could be a pop-up on a website. It could be a phone call, a banner head. It could be a search ad. Somebody’s looking for something and see a search ad such as Google AdWords at the top, that could be a nudge. An in-person sales call could be a nudge. They take all different forms but they all serve to get the customer’s attention and begin that motivation process.

On websites, you see dramatically different approaches to nudging. If we again continue the discussion of websites, sign ups, or newsletter sign ups on websites, some websites have the tiniest possible nudge, a little icon shaped like an envelope, or a little tiny subscribe button way off in the margin where it’s hard to see.

In contrast that with other websites, when you first go there, perhaps the entire first screen that you see is a suggestion to subscribe, showing you how you can benefit from that, or if not the whole page, at least a portion of it that’s very visible, and also often taking the form of, say, a pop-up or a slide-in or something of that nature where not only do you have a very prominent call to action, but there’s movement. There’s something that changes which definitely catches the attention of the visitor.

One thing that I like that LinkedIn does is sometimes they put your picture in an ad. One thing that advertising folks talk a lot about is the phenomenon of banner blindness in which people see ads but don’t really pay any attention ultimately. They mentally tune them out. The way LinkedIn breaks through that to make their nudges a little bit more effective is to put the picture of the visitor, whom is a logged in member, and they have the picture from their profile. They put that right in the ad, it makes it far more difficult to ignore.

In short, the nudge has to be seen and it has to start the process. It has to get their attention and also hopefully provide at least a little bit of initial motivation to get going down the slide in the same way that when mom or dad gives their kid a little shove at the top. It gets them off dead center and it gives them a little bit of momentum going into the slide itself.

Let’s talk about what happens next. The angle of the slide corresponds to the motivation that you provide. A nudge without motivation be like pushing a little kid onto a slide that was horizontal or almost horizontal, you can give them a nudge but nothing happens. There’s two kinds of motivators that we’re going to talk about. There are conscious motivators and non-conscious motivators.

Conscious motivators are what we usually think of as selling points. Things like features, benefits, discounts, specifications, those kinds of things that are all very appropriate to the rational part of our brains. Non-conscious motivators, on the other hand, are things that have an emotional appeal, that employ psychology, and perhaps even occasionally, exploit what some people call brain bugs, little quirks of the way we think that don’t always makes sense, but are simply a fact of human nature and human wiring.

The reason non-conscious motivators are so important is because that scientist estimate that only 5% of our decision-making processes are conscious, the rest are non-conscious. If we’re focused exclusively on those features and benefits, we’re overlooking the opportunity to sell to the other 95% of what’s going on in people’s brains. To be successful, you need to include both conscious and non-conscious motivators. Some examples of conscious motivators will be things like, “Oh, a typical customer saves 25%,” “Our product has twice the power,” “We have a money-back guarantee,” all very good benefits that appeal to people.

Gifts and discounts are particularly important in many situations, particularly e-commerce situations where they may offer you free shipping or 20% off until midnight. Gifts are great too. Many subscription sites offer, for instance, an eBook or access to some videos that are exclusive and so on. If you’re doing surveys, you may have to do something like a bribe in the form of, say, a $10 Starbucks card or something because otherwise, there’s simply not enough motivation to complete your survey.

The problem with conscious motivators is that they are often very expensive. If you have to offer free shipping, if you have to give big discounts, offer buy one get one free deals, or even build an additional features into your product, all of these cost money and it can really hurt the profitability. Sure, you can always increase conversion rate if you offer an ever better deal, but you may not make any money.

Similarly, if you’re trying to get leads, if you offer ever more bonuses, you’ll be able to step up the leads, but even creating content you’re going to give away for free has a cost associated with it and it may also reduce your future sales opportunities. That’s why we like to focus on non-conscious motivators which are usually free or mostly free. Often they’re just involved copy changes, design changes and that sort of thing, and they can be very effective and even more powerful than any conscious motivators.

There are probably thousands or maybe even more kinds of non-conscious motivators and we’re not going to take the time to look at many of them here today. There are certainly lots of great books you can read on this topic, but let’s just take one example: the Concept of Liking, which is one of Cialdini’s Six Principles.

One company that makes a great job with that in their website is PetSmart. If you navigate to their About Us page and look at their executive photos, you’ll find that every one of them is holding a pet of some kind. Typically, big fluffy pets, cats, dogs, large dogs, and they all look really happy about it, which is great because what they’re doing with these photos is showing that they have something in common with their customers. That is a key principle of liking. If you can show shared attributes, then your potential customers will like you more and be more likely to buy from you.

What these photos are saying to their customers is that we are pet owners just like you. We love our pets and you can trust us to do a good job. Probably the only criticism I have of PetSmart is that that particular page is very hard to find. I had to click on a footer link and click a couple more times in order to find it. If you want to use this yourself on your website, you need to put these liking cues and these potential shared attributes that you have with your customers front and center. Put them on a home page, on the landing page, where people are actually going to see them when they’re in that decision making process.

Another non-conscious motivator is the concept of free. Actually, of course, that’s a conscious motivator as well. If you see that you get a free product, your brain’s going to say: “Well, it sounds like a good deal.” Dan Ariely has shown that free has a special place and it is not the same as very cheap. Clearly, if you offer free stuff it may cost you money, but oftentimes I see websites and retail stores and other entities that offer deals like “Buy one get one for 1 penny” or “Buy one pair of these, get another one for just $1.”

Now, those may represent incredible deals, but they are not the same as free. Ariely conducted a classic experiment involving chocolate Kisses and truffles and conclusively demonstrated that even a penny made a big difference in people’s decision making, even though logically it didn’t make any sense. The point of that is if you are going to offer some kind of a very inexpensive deal to induce people to buy, don’t attach a very low price to it. Make it free and that will be far more appealing to the customer’s subconscious than even your very cheap offer.

One of Cialdini’s other Six Principles is the concept of scarcity. The classic experiment that showed scarcity was important is about chocolate chip cookies, in which cookies that were in a jar that contained two cookies were perceived to be tastier and more desirable than the identical type of cookie in a jar that contained ten. You see websites exploit the concept of scarcity very effectively.

Travel sites often are brilliant at this. They constantly show you there’s only one ticket left at this price, there’s only four rooms left. Sometimes they’ll even exploit another kind of scarcity which is decreasing quantity or increasing scarcity, which is an even more powerful motivator. You’ll see things like, “We’ve just sold two of these rooms today and there’s only one left.”

These are very, very powerful motivators. Obviously, certain kinds of products you have that inherent scarcity. Airplane seats are in limited supply and when they’re gone, they’re gone typically. You can create your own scarcity. You can, for instance, say, “Only so many of these will be available,” “Only so many will be sold at this price.” You can add your own scarcity to these things.

Now, I could go on and on with all different kinds of examples of non-conscious motivators, but I encourage you to read some of the great books on the topic. You’ve got Cialdini’s “Influence: Psychology of Persuasion” is a classic in the field. Nathalie Nahai, who was my first guest on the Brainfluence Podcast, has a great book called “Webs of Influence” that goes a lot into this psychology of web design. Another friend of mine, Leigh Caldwell, wrote an entire book on “Psychology of Price.”

Now, my own book, “Brainfluence,” has 100 different short chapters that give examples of how to employ some of these non-conscious motivators, both on the web and in other situations. There are a lot of books. Dan Ariely’s “Predictably Irrational” isn’t a business book per se, but it really will give you some keen insights into why focusing on some of these non-conscious factors is important.

With having said that, let’s move on to the element of the slide that is friction. Friction has two components, perhaps much like the motivation component. There’s real friction, which is difficulty in completing the process of persuasion or being persuaded, and perceived difficulty. Both are really important. Friction on the web can take many forms.

If you look at the number of steps in a checkout process for e-commerce, every time you have more steps, that increases friction. Form fields are friction. More fields always reduce conversion. Lengthy instructions, customer confusion are a common source of friction. When a customer gets to a particular point in the conversion process, and if it isn’t absolutely clear what they’re supposed to do next, there is a chance that they will bailout without completing the conversion process. Just about anything in the conversion sequence can be friction. As a result, you want to eliminate anything that’s not essential and hence reduce friction.

Not too long ago, I clicked on an email link to read an article. The email said, “Hey, read this interesting article.” It was on a relevant topic so I clicked through and I did not get the article. Instead, what I got was a form with about twelve spaces to fill out in it before I could read the article. Not only were there a lot of fields, but some of them had really confusing questions. Things like “Do you currently have a solution?” I don’t even know what the solution was for, how to know if I had it. Things like whether I plan to buy solution within the next six months, things like that. What I did, and I imagine many other people did, was they took one look at that form and immediately hit the back button. That’s a great example of how friction can kill conversion.

I’ve looked at the e-commerce checkout process. One of the phenomenal statistics is that a $1.8 trillion worth of merchandise is left in e-commerce shopping carts every year. That represents a tremendous amount of waste where customers were induced to visit the website. They shopped. They actually decided to buy something, but somehow probably due to friction in many cases, they did not complete the checkout process.

A great example that I’ve seen is the Staples checkout form which occupies probably about five screens on a typical PC monitor resolution. It’s just a very, very long form that has even some little paragraphs of instructions on how to complete it. I’m sure that many people who wanted to buy some simple product, an ink cartridge, would get to that point and say, “Oh gee, this looks like it’s going to take too long. I could jump in the car and drive to OfficeMax in the time it would take me to complete this process and I’ll have the product right away.” Those are examples of friction.

On the other hand, take a look at what Amazon does with its Prime customers. They have figured out how to virtually eliminate friction in their ordering process. They have a little box that appears if you’re logged in Prime customer. On every product page, it shows you when you’ll get the product. For instance, you’ll get it for free on Wednesday. It shows you where it’ll ship it. It’ll ship it to your home. If you’ve setup an office address, there’s a simple little dropdown to change that. Then there’s a “Buy Now” with one click button.

When somebody presses that, there is no chance that that is going to be abandoned in a shopping cart later. That transaction is complete when they push that button and they make the decision to buy. Amazon, as I say, has essentially eliminated friction from that particular process and does not suffer from the abandoned merchandise problem that virtually all other folks do.

Another kind of friction is what’s called choice architecture. If you look at organ donation rates of all things in European countries, there’s huge disparities where some countries like Denmark and Germany have very low rates, like in the 4% and 12% range of organ donation where many other countries like Belgium and France are up in the 99% range. Now, it’s not because some people are nicer people than others in the different countries, but it’s because of the way the choice is structured.

In the countries with very high donation rates, and most of the European countries are up in the very high 90’s, it’s because it is the default choice if you register your vehicle or register to vote or get a driver’s license. The default choice is to be an organ donor. You have to opt out. Where in the countries with very low donation rates, it’s the reverse. You have to opt in, and probably the very low rate countries such as Denmark … it’s only 4% donation rate … make the opt-in process rather difficult and onerous. The message there is that if you can make what you want your customers to do the default choice, that is the minimum friction path and your conversion rate will go up.

Now, let’s talk a little bit about perceived difficulty. That’s different. I mean if you’ve got a million form fields to fill out, that’s real difficulty. There are certain factors that make things appear to be difficult even if they’re not.

Adam Alter did a great analysis with his grad students of a confession site to change from a fluent design. Fluency is a key concept. Fluency is how difficult something is for our brains to process. It went from a white type on a black background which is pretty hard to read and that would be a disfluent design to a very easy to read normal white background with black type. What Alter and his grad students found was that on the more fluent site, the easier to read site, people were much more revealing in their confessions. The mere fluency effect caused them to be more likely to be persuaded to give up some of their rather embarrassing confessions.

In another case, and this is from Which Test Won, a site I highly recommend. It’s whichtestwon.com. They, every week, have an A/B test often with surprising results. They showed an order form with two guarantees. One, very simple, you may cancel at anytime. The other was personalized. For instance, “John, your satisfaction is fully-guaranteed. If we’re not what you had in mind, feel free to cancel. Blah, blah, blah. We’re here to serve you.”

It was a very reassuring text, a combined personalization which we know usually increases response and some additional reassurances. In fact, what they found was that the short version, a very simple guarantee convert about 15% better. I’m quite sure that was a fluency effect. It was simply easier for people to process that short line of text than to read the perhaps a more reassuring but longer version.

Then the classic example of fluency is the experiment done at the University of Minnesota where people were asked to read two sentences that describe an exercise program and estimate how long it would take to do these short exercises. The text was something like, “Tuck your chin into your chest and then lift your chin upward and do six to ten repetitions.” The text was the same for two groups except one saw it in Arial which is an easy to read sans-serif font and the other saw it in brushy which is a hard to read font.

Amazingly, the people that read that in Arial said that it will take about eight minutes to do and the people that read it in the brushy font … again, the exact same text … estimated it would take almost 15 minutes. You can maximize your conversion and minimize perceived friction by using simple fonts, short text, and easy to read design.

Now, there are lots of things that can add friction to a site. Any kind of bad user experience certainly does that. Things like CAPTCHAs are friction, especially those that are almost impossible to read and decipher; things like super strong password requirements that people are likely to forget; not allowing passwords to be saved on your website. We really don’t have time to go into all the details. Just if you design for good user experience, you will be eliminating friction as you do that. That’s friction.

In closing, let’s look at the key elements again of the persuasion slide. First, you want to align your offer with gravity. That is align your offer with what the customer’s motivation is. If the customer is looking to lose weight, be sure that you’re describing whatever you have in terms of how it’s going to help the customer lose weight or make money or achieve business success, whatever their motivation is. You want to be talking about their needs, not your needs.

Then you have to start with a nudge. You have to get their attention whether it’s a prominent call to action, a pop-up, an email. Somehow you’ve got to start that process and that nudge should include some motivation factor in it. In other words, it should get them moving down that slide a little bit by showing how you will benefit what they want or what they need.

Then you want to maximize the angle of your slide which is you want to maximize the motivation that you’re providing the customer. Those are both conscious motivators, things like features, benefits, prices, and so on and non-conscious motivators which we talked about at some length. The steeper the slide, the more motivation you can provide, the more likely they are to get to the bottom of it and become a completed conversion. Also, remember that non-conscious motivators almost always cost less than conscious motivators.

Lastly, we want to minimize friction in the process. Minimizing friction is usually the cheapest way of all to maximize your conversion rate and persuasion success. It’s almost always cheaper to just simply eliminate barriers to the process than to try an increase motivation in any way.

With that, we have done our very quick summary of the persuasion slide. I encourage you to check it out in more detail. Probably the best starting point would be RogerDooley.com where you can find links to my Neuromarketing blog, my Brainy Marketing blog at Forbes.com. Also, if you check the show notes for this podcast, you’ll find some specific links to Persuasion Slide content and explanatory graphic that shows the different components of the Persuasion Slide.

That’s it for now. Thank you so much for listening to this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. By all means, if you haven’t done so, please take a moment to rate us at iTunes, Stitcher, or the player of your choice. That helps us be discovered by other potential listeners. Thanks again. This is Roger Dooley, closing out this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.