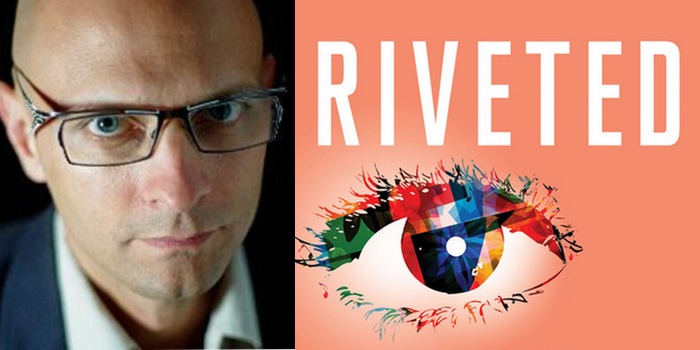

When reading a book or listening to a story, have you ever pictured that scene in your mind; how the scene would play out and what it would look like? This is using your imagination, and that is exactly what our guest this week on The Brainfluence Podcast studies. Jim Davies is an associate professor at the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University, director of The Science of Imagination Laboratory and author of the book, Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe.

When reading a book or listening to a story, have you ever pictured that scene in your mind; how the scene would play out and what it would look like? This is using your imagination, and that is exactly what our guest this week on The Brainfluence Podcast studies. Jim Davies is an associate professor at the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University, director of The Science of Imagination Laboratory and author of the book, Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe.

Using computer software, Jim and his associates are recreating the visual scenes formed by our minds in response to stimulus. By doing this, his team is attempting to understand how the mind creates these scenes and what is happening in the brain while imagination is being used. Jim’s work explains why visual thinking is a powerful problem-solving technique and how the mind visually constructs situations and even different worlds.

Jim’s Book, Riveted, breaks down the similarities between what attracts people to art, religion, sports, books, and gossip. The goal of Riveted is to find what ties all of these things in our world together, why certain pieces of art compel us, or why a book can hold our attention for hours. In his book, Jim strives to help readers to be open to new information and stimulus. Listen in as Jim explains how to become more compelling in both your brand and your business to capture the imagination of your customers.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast, and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Jim’s foundations of “compellingness.”

- What makes something compelling to our minds.

- Why incongruity and a longing for understanding are driving factors.

- How telling a story can make any piece of art or sports event more compelling.

- Why scientists need to find ways to incorporate stories into scientific explanations.

Key Resources:

The Science of Imagination Laboratory

Jim Davies: The Blog

Jim Davies on Twitter: @DrJimDavies

Book Website: Riveted by Jim Davies

Amazon: Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe by Jim Davies

Kindle Version: Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe by Jim Davies

Jim’s Psychology Today Blog: The Science of Imagination

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. This is Roger Dooley and today, we have Jim Davies with us. He’s an associate professor at Carleton University’s Institute of Cognitive Science, and the director of The Science of Imagination Laboratory. Jim is also the author of the brand new book, Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe. Jim, to start off, why don’t you tell us a little bit about what you do at Carleton?

Jim Davies: At Carleton University, I’m the primary investigator for the Science of Imagination Laboratory, and what we’re trying to do there is to understand human imagination. By that, I mean how people picture scenes in their heads, so if they’re reading a book or they hear a story, or they’re just lying and daydreaming, or fantasizing. How does their mind decide what things go in that picture and where do they go?

The way we approach that is with computer modeling. We’re trying to make computer software that comes up with visual scenes the same way that people do. If you ask the computer program to imagine a mouse, for example a scene with a mouse in it, it’ll try to pick other things that go with mouse like a mouse hole or a cat, or something like that and try to put them in the right place. By doing that, we’re trying to understand how people’s minds create these scenes that they see in their mind’s eye.

Roger Dooley: First of all, let me ask about the laboratory itself. I hear about The Science of Imagination Laboratory. Does it look pretty much like every other lab or is it something like a Disney movie set?

Jim Davies: I’m pretty sure it looked more like a Disney movie set. It’s really a bunch of people with computers. We’re making software and we’re using photo databases as the input for the software. We don’t have a really big, great looking laboratory yet but I do have dreams someday of having it look like it deserves the main of The Science of Imagination Laboratory.

Roger Dooley: I guess I let my imagination carry me away.

Jim Davies: That’s part of what we study. If you hear about The Science of Imagination Laboratory, we want to know what happens in your mind that brings to the fore the scene that you made in your head.

Roger Dooley: I’m visualizing a lab that’s throwing big, colorful foam balls at each other and things. Now, imagination and photos are kind of different things. You mentioned that you worked with image databases and whatnot. How does that work when people are imagining a mouse, a computer can certainly retrieve pictures of mice that are stored in the database labeled as mouse pictures like Google does finds on its own and figures out that it’s probably as mouse. That isn’t quite like our own imagination it seems.

Jim Davies: That’s right, that’s right. You’re getting on something that is well known and that’s our mind does not remember things like photographs. It doesn’t store them like a photograph. What we’re doing with the pictures is not saying so much that our imaginations are like photographs. But, that photographs are a substitute for human visual experience. What we’re trying to do is create realistic scenes. If I said, “Oh, in kitchen today, I had bacon and eggs.” If you picture that, you’re presumably drawing on your visual memory of having seen bacon, eggs, kitchens and you’re going to put things in that visual image according to what you’ve seen before.

The great thing about a photo database and we’ve a labeled photo database, we know what objects are in the images is that we can mind that for regularities. If there are eggs in the image, what other things are likely to also be in that image? That’s the reason we’re using a photo database. The final output of the system that looks like a surrealist collage at this point in the research isn’t as important as choosing what goes where, and the photo database gives us information about the world that presumably matches to what they’ve seen.

Roger Dooley: How does imagination relate to creativity? They aren’t exactly the same thing, right?

Jim Davies: No, they’re not. Imagination is often used to mean creativity in certain contexts and of course, in my laboratory, we’re focusing on imagination and the visualization of scenes. But certainly, the imagination is used in many creative acts although not all. There’s a famous story that Mozart could imagine his entire symphony before he wrote it down, and that’s audio imagination rather than visual imagination but it’s still a sensory kind of imagination.

But then, there are novelists who we might say have a really great imagination but they’re thinking in words and they might be particularly visual people. They might have vivid images of their characters and the scenes, and everything that happens in their book but they might not. Creativity in word play, in problem solving can be imaginative but it need not be. Imagination is a tool that can be used in creativity but not always.

Roger Dooley: Does your lab actually look at any creative applications of imagination or it’s still focused more on the mechanics of imagination?

Jim Davies: Yeah, well, we are in that if you can get a computer program to imagine realistic but novel scenes like scenes that resemble reality but actually never been seen before which is kind of our goal with the laboratory, then there are applications down the road for generating, let’s say three-dimensional environments for virtual reality or for training, or for video games, or for computer-generated movies, these kinds of things. There’s a lot of effort that it takes to create these environments and if we can get computers to help out the artists, then they can just create a lot more.

Roger Dooley: Let’s move on to your new book Riveted.

Jim Davies: Sure.

Roger Dooley: It has an impressively long subtitle by the way. I was joking with my friend and also fellow podcast guest here, Chris Goward a few weeks ago about his book subtitle which was quite long and actually had sort of an A and B version incorporated into it. But yours could probably give him a run for his money in terms of word building but …

Jim Davies: It’s a long title but it was tough. We went back and forth a lot on the title because the book is trying to cover so much. Actually, I talked about in the book how titles have gotten shorter over the years. If you look on Wikipedia, the original title for Robinson Crusoe or The Mutiny on the Bounty. They’re hilariously long. They’re like, five lines long. I like the short Riveted but I acknowledge that there’s a long time.

Roger Dooley: Right, right. I think the combination of a single word and then sort of an explanatory subtitle makes a lot of sense. It works for Malcolm Gladwell anyway. You’re covering a lot of ground there; jokes, movies, religion. Why don’t you give us just sort of a sense of what the overall thrust is. You’re really trying to come up with sort of a unified theory of imagination, aren’t you?

Jim Davies: I’m trying to come up with a scientific description of why we find things compelling, why we pay attention to things, why certain things we find riveting? And that’s where the title comes from. That’s what ties together sports, and gossip, and art, and religion, and all these things is because they move us. They make us feel something very deep inside that makes us want to attend to it, and that is the essential mystery that my book is trying to crack.

It’s really broad because as far as my reading anyway, I’ve never seen anyone try to tackle compelling across all of these different fields. There are books about art, there are books are religion but nothing that shows that these things actually have similarities and that we are attracted to art, in religion for examples, and sports for very similar reasons.

Roger Dooley: I think riveted is probably a better single word than compellingness for a title, but I think compellingness really is an explanatory word. Is there really common thread here or is it simply that these things are compelling in very different ways to people or can you … Have you sort of found a common element that says, okay, this is why religion is like a movie, for example?

Jim Davies: Right. There’s no one thing that makes something compelling. It had to be a whole book because it’s not something simple. But just to give you a preview, we will sometimes read religion of the past as fiction. If you look at a lot of the Greek myths for example, we make movies about them, we’ve got all kinds of … We’ve been reusing those Greek myths because they’re great stories. They’re just great stories. We read stuff that people really used to believe in their hearts and souls actually happened as fiction now.

Anyway who has … even a cursory familiarity with the stories in the Bible for example can attest to that they’re really good stories. My point is that religion would not have been successful if the stories were boring, if the stories didn’t move us in some way, if the stories weren’t good in the same way that literature is good; then, they wouldn’t have been successful. What I do is in each of the chapters, I talk about a different foundation of compelling, so I call them foundations. I’ll talk about one for example.

Incongruity is one of the chapters. Incongruity is when you look at something and it’s not quite right or you don’t understand it, but there’s kind of a promise that you can understand it. A mystery story is a great example. In the beginning of the mystery story, there’s this incongruity. What happened? This doesn’t make sense. What’s going on? Many, many television shows are based on this kind of thing. Art works that show bizarre situations and even music videos that have these incongruous things. They draw us in and they make our mind wrestle with it.

You can look at the longing for understanding as a driving factor. In sports, we don’t know the outcome of the game, and a game is much more boring if we know who’s going to win, for example. The incongruity in understanding religious scripture is a big deal, so people can read religious scripture and it’s not exactly clear what it means and people will read it to try to find something relevant to their own life.

In artwork, we know that having too simple of an image, one that’s too symmetrical or the patterns are too obvious, we might find it pretty but we’ll rapidly get bored of it. The great works of art are ones that keep giving. They are endlessly fascinating for people who choose to keep looking and trying to find new mysteries and how the work of art solves it. That’s why I think that they deserve the same treatment. I might be wrong. This is my book and readers can decide for themselves if I’m on to something.

Roger Dooley: Right. One common thing that you brought out too is stories. To me, that’s something I’ll write and speak about often. You know, the power of stories in communicating and some of what I talk about it based on evolutionary psychology where some would say that these stories were big, evolutionary advantage and that’s why we still pay attention to them in a special way because one member of a community could communicate to the rest of the community where the danger was, where the new food sources were, even more complex and that was a great advantage over other species that had to learn more less experientially. Obviously, things like art aren’t necessarily story based but is story a common them across some of these compelling topics?

Jim Davies: The presence of a story is usually really good for something to be compelling, I’ll put it that way. But there are plenty of exceptions. It’s hard to describe a basketball game as a story in any kind of meaningful sense. It has characters and it has conflict but it’s not really a sensible story, and a lot of music isn’t a story particularly baroque music. It’s not intended to tell a story.

Roger Dooley: Although it’s interesting that when something like the Olympics are being broadcast, often stories are inserted to make the sport more interesting.

Jim Davies: That’s right.

Roger Dooley: In other words, it’s not just 10 archers that you never heard of instead folks and a few of them talk about their life history and how some crises they overcame and great obstacle they overcame, and that story makes the athletic contest more compelling.

Jim Davies: Oh, yeah absolutely. We want to, “Oh, this person is the underdog and they came from this tough background. The competition between two athletes has been going on for years and they broke into a fist fight, or … ” you know, things like that make things more compelling. Also with music and art. People tend to be a little bit more interested in the art if there’s a story about the artist, right? It’s not really changing the art itself in any way. It’s not changing the pain on the canvass or it’s not changing the notes in the music or the sound file.

But, yeah, stories are incredibly important and in fact, one of the reasons that scientific explanations sometimes have trouble competing with religious explanation of the same phenomena, say the origin of the Earth or evolution is that the scientific explanation often isn’t any story in any meaningful recognizable way. It doesn’t have characters. It doesn’t have desires and obstacles toward their goals. Because stories are so compelling to us, competing explanations that do feature stories, that do feature characters have a kind of advantage.

Roger Dooley: Interesting. There might be some good advice there for what scientists are trying to communicate, to say about the importance of vaccines against a small number of folks who believe that they cause autism. I think the way it characterized it, it’s right. You’ve got scientists putting data and charts up, and then a mother is saying, “Well, my kid has autism and it appeared two weeks after he was vaccinated.” It’s no proof of cause and effect relationship but this story is far more compelling than a bunch of charts.

Jim Davies: That’s right. Anecdotes are stories in the way that charts are not. In fact, if a lot of science teachers will use … How do I put it? They will scientific explanations into stories to make them more digestible for the human mind. They might say, “When the water flows down, it tries to find common level,” or something like that. Now, this is a scaffold, right? The waters don’t want anything. It’s just following its natural path. It’s not an agent that has preferences and desires.

However, thinking about the water wanting to do something or a thermostat wanting something is a way to not only help people understand it but help them believe it.

Roger Dooley: Sure. Right, that makes sense. Thermostats calling for heat as if this thermostat is saying, “Hey, I’m too cold.”

Jim Davies: That’s right. That’s right, yes, exactly.

Roger Dooley: Which of course, it’s a little bio metallic strip going click in there but it’s more anthropomorphizing it really makes a difference.

Jim Davies: Yeah, and it really does help people understand it. It’s actually easier to understand a thermostat in terms of desires. Like the thermostat wants it to be this temperature so it turns on the heat or it turns on the cold depending on the actual temperature. It’s easy to remember. It’s easy to recall. It’s easy to make sense of, and that’s because we are human beings who love stories.

Roger Dooley: You talked about religion and superstition in the book. You just mentioned the importance of religious stories and so on. Why do some societies seem much less compelled by religion in thinking of, let’s say a modern day hero but it’s almost completely secular now it seems where other societies are just totally driven by it?

Jim Davies: I think that the secularism that we see in Europe, much of it there’s less church attendance in this kind of thing, still a very decent size … A decent proportion of the population believes in God so in some sense, they are still religious people. The outward trappings of religion are not quite as common but it’s still there. In terms of why some societies are more religious than others, that is mysterious. I’m not going to pretend I know the answer to that but I will say that there are some suggestive findings in psychology and in anthropology.

One is that people will get more religious when they’re frightened or threatened, and if they feel out of control or they feel that their world is chaotic. They will search around for … If there are religious ideas around, they will grasp on to them. They also are more likely to form superstitions. This was found experimentally even with pigeons, and B.F. Skinner a long time ago he said that, “If you give pigeons food randomly in a room, they will superstitiously think that bowing their head or turning around, or whatever they happen to be doing at the time cause the food to come out, and so you get 10 pigeons there all doing different superstitious behaviors trying to get the food.” People are the same way.

You find for example, for the fishermen, if there’s a group of fishermen that fish sometimes in the ocean, sometimes in the bay, this is an anthropological finding. Fishing in the ocean is much more chaotic. It’s less reliable, and a lot of the superstitions that this society has and religious beliefs are based on the ocean and not on the bay. Baseball players, similarly, the batters and the pitchers have all kinds of superstitions. You can see them do all these strange pigeon-like behaviors right before they do their thing but you don’t see that with fielders, outfielders. You don’t see left fielder touching his hat and wiping his hand as the balls are coming out because it isn’t much less … or it’s a much more predictable environment.

Roger Dooley: That’s pretty interesting. Do people really read People Magazine to find out what’s changing the social structure? To me, the people who are pictured in People really don’t seem to relate to my social structure very much, and they’re probably not most of the readers or is this just still of an evolutionary psychology, a throwbacks sort of thing?

Jim Davies: Right. Why are people so interested in celebrities that they don’t know and who frankly have nothing to do with their lives? The answer that I offer is that most of our minds when we’re consuming these stories and seeing these pictures, most of our minds don’t know that that person is not really right in front of us. Now, if you look at our evolutionary history, the vast, vast majority of it up until very recently, we had no images at all really. There were very few instances where we would see something that wasn’t actually real, an image being a representation, a photograph, a painting. Even paintings were very rare up until recently. People didn’t see that kind of stuff.

Our minds really didn’t have any evolutionary pressure to distinguish really strongly from fiction and reality. When we see someone on television or we see them in a magazine, part of our mind thinks that they are members of our community and it’s important to know about what they’re doing particularly if they’re high status. The high status people don’t need to pay attention to low status people because the low status people don’t matter. But the low status people pay very close attention to high status people. They want to befriend them, they want to mate with them, or whatever and this bleeds over into celebrity interest.

Roger Dooley: One point that you make is that people can’t really predict what they like, and explain that a little bit because that’s a point that I make an awful lot in talking about on your marketing techniques but explain them, your perspective on that.

Jim Davies: The reason people are not really great at predicting what they like is in part because most of their minds are really unknown to them. What you’ve conscious access to is just the icing on a very large cake, and things happen in the cake that your conscious mind and your deliberative processing can only theorize about. It doesn’t always feel like theorizing. That’s the hard part of being a human being is that you get these feelings and you try to make sense of them, and your explanations feel just as real as the feelings but they might not be, so you might predict things about yourself that end up not being true.

If you ask people for example who live in the Midwest, would you be happier living in California? What they tend to do is they focus on the most salient difference in their minds between where they are and where they might go. The sun, so they think, “Oh, it’s sunny days all the time. Yes, I’d be so happy.” It’s silly, right? Most of your happiness is or I would say, a very small part of your happiness is based on the weather. But if you’re only focusing on one little thing, you can make these really bad predictions.

If I were to give advice to people, it’s to, you know, I think it’s good to know thyself and to reflect on what you like and don’t like based on what you’ve experienced but it’s always good to be open to new forms of art and new kinds of people because you are not an infallible expert on your own preferences, and you might surprise yourself.

Roger Dooley: Right. I just wrote a piece a couple of weeks ago on Forbes about a Gallup poll that got a tremendous amount of press coverage particularly in the digital space. They found that 62% of all social media users said that social media had no influence on their purchases. This of course was trumpeted by a lot of people saying “you see, the wall on Facebook really doesn’t work,” isn’t good for two-thirds of the people. They don’t even pay attention to recommendations, their friends, and whatever else that you see there. Of course, it’s totally bogus as a poll because people can’t explain why they made a purchase. They can’t tell you that it had not effect because there are probably 20 things that affected that purchase that they not even aware of.

Jim Davies: Right, yeah.

Roger Dooley: When you’re talking about compellingness, I like that word, is there a way for individuals to be more compelling, to be more interesting to those people around them? I think something like that will be a useful personal skill whether for business or personal life.

Jim Davies: Yes. I have my own personal tricks that I sometimes try to use but these are not really scientific findings. But in terms of the incongruity for example, I really don’t want to be boring. I’m a professor. I can talk for hours about anything, but I don’t want to bore people. What I’ll sometimes do is, if something comes up, I will say a little something and then leave kind of a teaser, and then wait for them to ask about it, right?

If someone says something about, “Oh, I find the color blue really relaxing.” I might say something like, “Oh, they’ve done some studies of the color blue about how calming it actually is,” and might just leave it at that. If the person’s not interested in hearing about scientific studies which of course many people are not, I just let it go. But what I’m doing is implanting a seed and if they want to water it, I will continue talking. I feel like that’s part of being a good conversationalist for example. I think people like you more if you don’t talk their ear off about things they don’t want to hear and let them ask for what you want.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think it’s certainly good advice that probably not all of us pay attention to as often as we should. What about businesses? Is it possible to be more compelling as a brand or to have more compelling products?

Jim Davies: Yes, absolutely. I think that a lot of what I say in my book is not going to be news to people particularly in the creative, in advertising, or in the arts or something like this. What I’m trying to show … I’ll give you an example. I have a book on stage directing for theater directors. One of the things it says is that motion from left to right on the stage and from the audience’s point of view is more powerful than motion in the other direction. This is a bit of folk wisdom in the theater community. It turns out to be true. Now, we’ve done experiments and we found out that it’s actually because of the direction that we read.

People who primarily work in Arabic or Hebrew for example, they actually like direction going the other way, and even referees will call more fouls on people who are moving opposite to the way they normally read. What my book is trying to do is to show why these things work. An artist or an advertiser might know that this is good and this is going to grab people’s attention. My book is there to try to help that person understand the underlying psychology of how that whole thing works.

For example, the presence of people is almost ubiquitous in art. I did a survey of paintings, famous paintings and other artworks and found that people vastly outnumber other animal for example, and they vastly outnumber paintings that don’t have any people depicted in them because we are so interested in social connections. I would say for a company who wanted to be compelling, having this human side, being relatable as a kind of a … in personal way could be very valuable.

Roger Dooley: That’s certainly good advice too, Jim. We’re just about out of time so let me remind our audience that Jim Davies is the author of The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One With the Universe. Jim, how can listeners find your stuff online and connect with you if they want to?

Jim Davies: The book Riveted can be found on Amazon and in bookstores across the continent. If they want to read more about, they can go to jimdavies.org or jimdavies.org/riveted and they can read book reviews, and I have some other kind of information and mailing list for related features. I have a blog on Psychology Today on the Science of Imagination where I will be posting related things.

One of the fun things on writing a book is I had to cut a lot of things, and the great thing about the modern age is that those can be blog posts. If you like the book and you want to hear more, then I will be putting another third of a book worth of material out on the blog over the next year or two.

Roger Dooley: Great. Our listeners will find links to your book, you website, your Psychology Today blog, and so on on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com. Jim, thanks very much for being with us today.

Jim Davies: My pleasure.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.