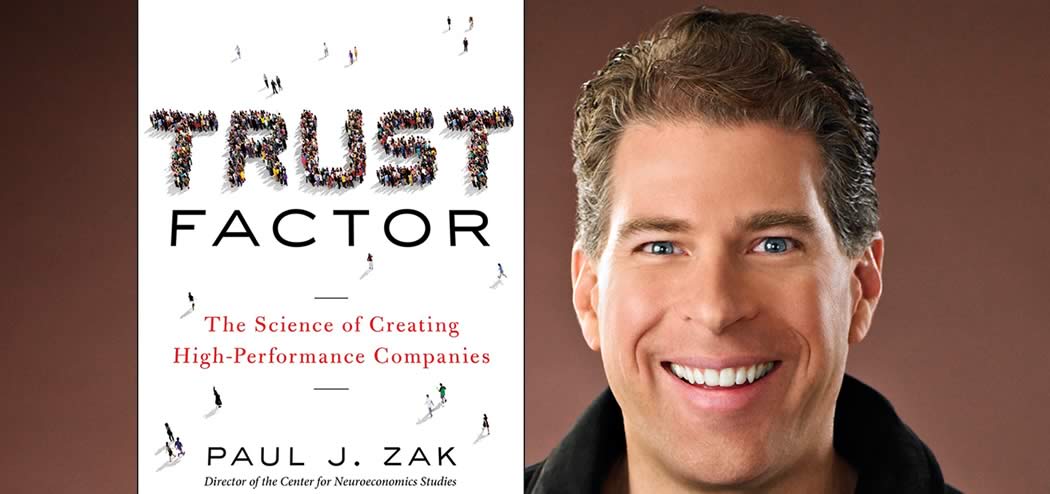

Today we’re speaking with Paul Zak, a field-defining thinker in neuroscience and repeat guest on the show. Paul has created waves throughout his career, first with his fascinating research on oxytocin and its effects on the relationships, trust, and morality that make us human. His latest book, Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High Performance Companies, uses neuroscience and practical actions to help you measure and manage your organizational culture to inspire teamwork and accelerate business outcomes.

Today we’re speaking with Paul Zak, a field-defining thinker in neuroscience and repeat guest on the show. Paul has created waves throughout his career, first with his fascinating research on oxytocin and its effects on the relationships, trust, and morality that make us human. His latest book, Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High Performance Companies, uses neuroscience and practical actions to help you measure and manage your organizational culture to inspire teamwork and accelerate business outcomes.

Paul is the founding Director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies and Professor of Economics, Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. He has degrees in mathematics and economics from San Diego State University, a Ph.D. in economics from University of Pennsylvania, and post-doctoral training in neuroimaging from Harvard. Paul’s research on oxytocin and relationships has also earned him the nickname “Dr. Love.”

Paul and I discuss the deceptively simple question underlying his new research: why do people show up at work? Paul shares how his research has revealed the importance of trust in productive organizational cultures, and how he’s applied his findings to help companies become more innovative and collaborative.

Paul is an outstanding researcher and communicator of ideas, and his work could really transform your organization from the inside out. Don’t miss this!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Whether your dog or cat loves you more, and how oxytocin affects our bonds with animals and humans alike.

- Why high-performing companies have high levels of trust embedded in company culture.

- The positive professional and personal effects of a high-trust work environment.

- Why you should change your company culture incrementally rather than attempt to overhaul it overnight.

- The two types of reactions companies often have when being told they need to improve trust within their organization.

Key Resources for Paul Zak:

- Connect with Paul: Website | Twitter | ZestXLabs

- Amazon: Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High Performance Companies

- Kindle: Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High Performance Companies

- Paperback: The Moral Molecule

- Kindle: The Moral Molecule

- How bringing your dog to the office could BOOST productivity

- Dogs Love Their Owners 5 Times More Than Cats Do, Study Reveals

- Video: Cat Friend vs. Dog Friend: If Humans Were Pets

- Claremont Graduate University

- Peter F. Drucker

- John Helliwell

- Tony Hsieh of Zappos

- Chris Roofer of Morning Star

- Goldman Sachs University

- McKinsey&Company

- TED Talk: “Trust, morality — and oxytocin?” From TED Global 2011

- Wendy Hoffman

- Jonathan Rubin, PhD

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week will likely be known to many of our audience members both because he’s a repeat guest and because his ground-breaking neuroscience and neurochemistry research has made him a celebrity in the neuro space. You’ll be excited to know that we’re going to learn whether your dog or cat loves you more with the neuroscience to back it up, but that’s not really our primary focus today.

I’ve invited him back to the show because he’s compiled a vast amount of research in a new book, Trust Factor, that makes a unique claim. Trust Factor is focused on how trust factors, as you might expect, are the most important drivers in high-performing organizations. He has identified eight of these that he says explain 100% of the trust differences in organizations. I read a lot of business books, and Trust Factor is one of the rare ones that I immediately wanted to send to some select colleagues who I thought could benefit from powerful insights in the book. By now you may have guessed that we’re speaking with Dr. Paul Zak, also known as “The Love Doctor,” and the director of the Love Lab. Welcome to the show, Paul.

Paul Zak: Thank you, Roger. Great to be back on with you.

Roger: Great. I have to say, I really enjoyed Trust Factor, Paul, and I want to spend most of our time on the ideas in that book, but before we get down to the serious business, let’s talk about pets. While I was reading your book, sitting on my sofa, my dog, who at 80 pounds isn’t exactly tiny, jumped up next to me, sprawled across my lap, and leaned up against me. It’s about as close to a hug as he can managed, although sometimes he does try and put his front paws around me.

I paused the reading for a minute and found this big, lovable mutt snuggling up to me. It was really kind of calming. Did he change my neurochemistry, and also, did his change?

Paul Zak: It’s a great question. We a couple years ago published some research wondering about whether dogs in the office actually matter or not, so we ran a dog versus cat study. We had people play with a dog or a cat, not their own, to see if it caused their oxytocin to increase, this chemical that I was first to show makes us trust people and makes us more empathic.

Secondly we want to know if the dog or cat causes your oxytocin release, which would be nectar to the humans, and the short answer there is that dogs are effective oxytocin stimulants, but only if you’re a pet owner. If you’re not a pet owner, you’re kind of dog-naïve, it doesn’t work. Cats don’t work at all.

Roger: Even for the humans?

Paul Zak: Yeah. They don’t really stimulate … Someone else’s cat, just a regular old cat for most people do not cause oxytocin release, and it turns out if you have a dog in your dog in your life or you interact with a dog, you actually are nicer to the humans in tangible ways, or share more money with them. You get along with them, and then about a year after we published that, the BBC asked me if we could ask the question in reverse: Do our dogs or cats really love us?

We write a study for them which played in the UK actually. I don’t think it’s come to BBC America, but we actually ran a full study in which we measured, took blood samples to measure oxytocin from dogs and cats before and after they played with their owners. Dogs had this huge increase of oxytocin when they interacted with their owners, and cats, not so much, a little bit, but not so much, so I think you’re right.

We created dogs to be kind of the perfect humans. They always love us. They don’t bring us down. They’re always there for us. Cats have resisted that domestication as much as dogs have apparently.

Roger: It seems almost kind of intuitive if you look at sort of the stereotypical personalities of dogs and cats. There have even been some really amusing videos, one I recall that had humans playing a dog and cat and mimicked their various behaviors and sort of exaggerated them. That’s exactly what you’d expect. The cat treats you with disdain and pays attention to you when you’re going to feed it, but dogs are very lovable. That’s great.

Paul Zak: That’s a perfect segue into the book, if I can, if I can interrupt you because-

Roger: By all means. Let’s talk about Trust Factor.

Paul Zak: Why are dogs and cats so different? It’s why people and cats are so different. Dogs are social creatures, and cats are loners. They hunt alone. They tend to live alone. Animals, like social creatures, like dogs and humans, like to work in teams. We actively effectively work in teams, and we have an underlying brain structure, neurochemistry that motivates us to work in teams, and so when we started working on this book about eight years ago we started running experiments measuring brain activity while people worked to ask why are some teams and some individuals more effective, more productive, more engaged with work, and why are other people less engaged and less productive? Is it just the people or could there be some underlying cultural environmental component?

That was the Genesis of the book, and I should be honest with you and the listeners: It wasn’t my idea. I had some business people come and knock on my lab door and say, “We think trust is kind of important in our organization. You’re supposed to be some kind of trust expert, so tell us what to do.” I didn’t really have good advice for them, so I had to start running experiments to figure out if trust mattered at all at work.

Roger: That’s great. Really the underlying theme in the book is that high-performing organizations are built on trust. That’s appealing, but sometimes we may be able to imagine companies that seem to thrive on internal competition or even sort of a dictatorial rule situation. What’s the evidence that trust really is important in businesses?

Paul Zak: The book marshals lots of evidence from specific companies I’ve worked with in which we’ve implemented these neuroscience-inspired notions to change the underlying culture, to improve trust. There’s before and after evidence. We also have evidence from other laboratories that have shown that components that we’ve identified as well as being the building blocks of trust actually have an effect on teamwork, on productivity, and lastly we collected in February 2016 a sample of over 1,000 U.S.-working adults and assessed the trust within their organization and asked them a lot of questions about their work lives, their family lives, their health, their weight.

Using all these measures we find that people who work in high trust cultures are substantially more engaged at work. They are more productive. They have more energy. They enjoy their jobs substantially more, and they also are healthier and happier outside of work. One thing we found in low-trust cultures is that individuals who are not happy at work are being micromanaged, and we can talk about why micromanaging, what that does neurologically. They’re heavier, and they’re sick more. They’re just not flourishing in life. If you’re heavy or sad and having fights with your spouse at night when you get home, how can you come to work the next day and be engaged, and excited, and happy?

We’ve tried to look at multiple streams of evidence to really make a business case that trust matters a lot. Again, it may make you feel good to think, “Oh, I’m going to create a culture where people are empowered to make decisions, and they can fail and not get punished for it,” and all that, but there’s got to be a real business case. The returns on creating a high-trust culture are substantial, again, in multiple dimensions.

Roger: Boy, after reading, after getting through the first third of the book even, I was convinced that we don’t really think about trust enough in our design of organizations, in our management structures, in the way we set up employee relationships and so on. One thing I found kind of remarkable, and maybe you can explain this, you identify eight trust factors which very conveniently can be labeled into the letters in the word “oxytocin,” but these factors you found explain 100% of the variation and the differences in trust between different organizations. Some of the eight factors alone explain upwards of 80%. Without going really deeply into the math, can you sort of unpack what you mean by those statements?

Paul Zak: In the book, to remind readers about the impact of each of these factors on organizational trust, I start each chapter by relating within our national representative sample of working adults, how much each of those factors relates to organizational trust. For statistics folks out there, I relate the r-squared. All these factors, as you said, run from about 45%, explain the variation of trust, to around 80%, so they’re all highly related to organizational trust. If you change one of them, you’re going to get a significant impact.

If it’s only 3%, then I can’t get so excited about it. Even if it’s statistically related, it’s not very meaningful, but each of those factors is not statistically independent, so they add up to more than one. There’s two ways to think about this, and if I put them all in a giant soup, like a linear regression, then there’s no more explained variation.

We span the entire set of possible policies that managers can use to influence trust with those eight factors. That’s good. In terms of application, I think those numbers are important for two reasons. One is that when we look at the effect of each individual factor on multiple performance metrics that work, we find essentially a concave effect.

The first part is called “ovation,” which is our word for recognizing people who are high achievers. If your ovation is already at the 85th percentile and you want to push that up to the 90th percentile, you’ll get a small increase in productivity and engagement by employees, but if you take ovation at the 35th percentile and push it to the 50th, you’re going to get a bigger effect.

I think those explain variation numbers are there to guide individuals on which factors to begin pushing on first. You can either push on the ones that are lowest, or you can push on the ones that have the largest effect on trust. Again, while there’s a bit of science in the book, as you said in your intro, it really tries to be extraordinarily practical so that individuals who are reading the book can implement this immediately. We do two things to make that happen. One is as you know after the end of the first chapter, there’s a URL, so you can actually get a snapshot of trust in your organization from your perspective.

Of course if you’re going to do an intervention, you’d like to get as many employees as possible to get feedback from them, but at least you’re getting a sense from your perspective of, what I should focus on first among these eight factors? The second thing we do is at the end of each chapter give you five things to do today. As you know, Roger, I was on the faculty with Peter Drucker for about 10 years at Claremont before he passed away.

Peter really had a big influence on me. He was such a humble, thoughtful human being, was a great listener, and was an amazing management guru for sure, but he was a very practical guy, which I liked a lot, so I thought, “We should in honor of Peter Drucker do the same thing.” Peter pretty much just said, “Don’t tell me what a great meeting you had; tell me what you’re doing different on Monday.” At the end of each chapter we have this thing called “Monday Morning Lists” in homage of Peter Drucker. The idea there is to read that chapter and then do something. Just try it. It doesn’t have to be perfect. I make that statement many times in the book. If you’re a leader, you can run experiments as long as you’re transparent about you’re going to try something: “Hey, I’m reading this book. It suggests that if we do this thing a little differently, it’s going to be great for the employees, and it will be great for the organization, so we’re going to try this for six months or three months and just see what happens. You guys can give me feedback.”

“Experiment” is such a nice word because it just says, “We’re going to try it.” Who knows? Sometimes the stuff in the book for whatever reason within an individual’s organization is not going to work because who knows, stuff that you can’t forecast. As you know, there are lots of examples and case studies, so you can copy what other high-performing organizations have done as a guide.

I really want people to do things, not just read and go, “That sounds great,” but really make an impact. To cap that off for the companies I’ve worked with to improve trust, when you walk in there, and you from a low energy, unhappy, non-excitable company to six months or a year later, and people are popping, and there’s open office space, and people are walking fast, and clients are happy, you think, “Okay, yeah, we did something kind of useful here.” The whole feeling of the place just changed because we empowered the people doing the work to be effective.

Roger: I do like the fact that every chapter does have a bunch of little anecdotes and examples of companies employing the various techniques that you describe so that, first of all, it makes it more readable. Stories always are much more readable, but also it make it easy to understand the implications of what you’re talking about.

One study that you site said that this study found a 10% increase in employee trust, and the company’s leaders had the same impact on life satisfaction as the 36% increase in salary. How would you even measure this? I think that’s an impressive statistic if it’s true, and I presume that it has merit, but that seems like kind of a hard thing to proof. You can’t quite put people on a brain scanner and come up with a, I don’t think, come up with that answer. Can you or can you?

Paul Zak: Yeah. That data was generated by John Helliwell, a well-known Canadian economist based on surveys. I’m with you, Roger. I’m always skeptical of people self-reporting things, particularly kind of feeling states, “How do you feel?” You know this, and your audience certainly does too. If you change the wording of that question a teeny bit, all of a sudden the answers are different, so I sort of came into this work asking the most naïve question, which is, why do people ever show up at work?

Everyone is a volunteer from a real functional perspective. You get paid, but we know pay is a very weak motivator, so besides pay, why else do you actually show up? Why do you put your heart and soul into this project? How do we understand that? We really started by running experiments while people worked first at my laboratory, then at a number of businesses, and a couple of them giving me permission to actually use their data, including Zappos, Herman Miller, so really well-run companies said, “Yeah, you can take blood from our employees. You can have them wear an EEG cap. You can have them do group tasks.” They were really cool to let me do that.

Roger: Those were really great partners.

Paul Zak: Gosh, they were wonderful, and we learned a ton, and a bunch of companies that we suppressed the name, but once we had enough data, then we turned those findings, those neurological findings, into a survey tool, and that’s the one that the book gives you a license to use, so that we wouldn’t have to take blood from so many people, first of all, which most companies won’t let you do, but also so that we could work at scale, so I can get 1,000 people at Zappos to actually take this survey. That’s actually what we did; we had almost 1,000 people at Zappos take the survey. Gosh, I’ve taken in three or four times at least, and a subset of those guys we actually took blood from as well.

We’re really trying to confirm that the factors we’re finding on these self reports correlate with what’s really happening in these businesses. Really when I started, I wanted to be naïve. I would get opportunities to speak at these different companies, and I would say … And say, “We’ll pay you something.” I said, “Don’t pay me. Just let me poke around. Let me come early and poke around and talk to employees.” They’re like, “Okay.” I would just sit and talk to employees: “What’s it like to work here? What do you do? How much time do you spend talking to colleagues? Do you feel like you’re supported? Does anyone care if you’re hear or not?”

I’d ask them all these kind of weird questions that our laboratory research suggested mattered to a affect productivity in the lab, but I wanted to see if it worked in the field. The first couple years was running these experiments with employees and then sitting and talking to people and just listening across all fields. One of our most interesting clients has been Morning Star Tomato, which was written up in HBR a couple years ago in an article by Gary Hamel called “First, Let’s Fire All the Managers.”

Morning Star is the largest producer of tomato products in the U.S., and they have no job titles. People have to self-organize. They hire individuals who can manage themselves, and this is heavy industry. This is planting tomatoes. This is harvesting tomatoes, running big machines, processing tons and tons and tons of tomatoes 24/7 for about six months during the harvesting season.

If it works in heavy industry creating a culture of trust, of engagement of self-management, which is one of the components that we find in trusting cultures, it can work in so-called knowledge worker industries as well. We really wanted to make sure it worked everywhere. Before you put all the stuff in a book and before you talk to clients and have them want to work with you, we really want to know that this stuff works. Everywhere would be impossible to know, but almost everywhere, everywhere that we’ve tried out of the US, in Asia and Europe. Anyway, lots of those stories in the book, and lots of data, but I’m with you. I think everyone should be skeptical, and that’s why I like the word “experiment.”

Even if it works at Zappos and it works at Herman Miller, and my book explains how to implement it, there are always slippage. There’s always an opportunity to not have this implement well. That’s why one of the key light motifs of the book is that culture should be thought of as any other business process. It’s an asset, and you should constantly measure and manage that asset for high performance, so just continually running these little interventions to improve work life for the individuals doing all the work, and then measure the outcome and measure.

If some of those don’t work, hey, you can go back to the status quo. No harm done. As long as you’re open about, “Hey, we’re going to try this. We think it’s going to be great for the people around us. If it’s not we can roll it back.”

Roger: I think the concept of this sort of experimentation will really resonate. It resonates with me and also will with our audience because many of our listeners are in the digital marketing space where AB testing and other kinds of testing have become very easy and very powerful tools. Something that I constantly emphasize if I’m giving a speech or offering any kind of advice is, “Okay, this worked in most other places,” or, “This has been 100% demonstrated as accurate in the lab, but you need to test it in your organization because you might be the exception.” He might be the one case out of 20 where it doesn’t work.

At least in digital marketing it’s pretty easy to run these kinds of tests. In organization design it’s a little bit more difficult, but having that kind of mindset that, “We think this is going to work. We’re going to try it and see if it does work, and if it doesn’t work, then we’re going to do it another way,” really makes a lot of sense.

You really don’t hear enough about that. Usually you see these organizational interventions as in, “Okay, starting Monday we’re going to have a new culture. Here’s what it’s going to look like.” That is probably almost doomed to failure when it’s completely designed in one fell swoop from the beginning.

Paul Zak: It is because people are used to the culture they’re in, and culture just really is their norms of behaviors that people have picked up. I think one of the key take-homes is that culture is not static, and you’re not stuck with whatever culture you have, but you’re right, Roger. You can’t do a culture reboot overnight. It just doesn’t work that way, but you can nudge people towards particular behaviors that we show will induce oxytocin release in others, improve teamwork, and just little by little.

The inspiration, just to be honest with you, the inspiration for this management experiment system that I outlined in the book is the Toyota Production System. Just like that system is set to just incrementally improve the efficiency of the production process, we should do the same thing for culture. The thing about culture is if you don’t manage it, it will manage you because the humans around you are going to start doing things that seem to suit them and may not suit the goals of the organization. I think once you have a measurement tool, then you’re going to be an effective manager and guide to that culture.

Roger: I think in a larger organization too, you don’t necessarily have to change everything all at once. You could pilot something. If you say, “Okay, we’re going to try this self-organizing team approach,” you could do it perhaps in one area of the business or even one department, and if it works there, then you can roll it out.

Obviously there’s some difficulties of saying, “Okay, we’re going to have some people doing one thing and other people doing something else,” but that would be a way to both demonstrate it and then also convince skeptics that, “Okay, this can actually work.”

Paul Zak: That’s exactly right, and that’s what most clients I’ve worked with will do, which is you can find the exemplars and the laggards within these eight building blocks of trust. Then first off all just copy, and copy the ones that are doing well, and then intervene in the ones that are not doing well. I’ll give you a concrete example. The big recession, 2008, 2009 I was working with a pretty large financial services company in New York that had, like everybody else, taken big hits. They were facing layoffs.

One of their divisions in the Midwest had even before the recession had annual turnover of 100% employees, so every years they were replacing everybody on average. It was entry-level division, and they would hire people right out of college who were energetic and fresh-faced and excited. After a year they just were burnt out.

Their problem objective there was employee turnover was too high. We were using the financial crisis as an opportunity to do culture change, and this company survived and turned around quite nicely, but I’m a big believer in not letting any crisis go to waste, so one of the pain points in this particular division was employee turnover.

We collected data, and we found that one of these eight components that builds a high-trust culture, which I call “invest,” which is spending resources to improve personal and professional development, it was just non-existent. I talked to the VP there, a big Texan guy who a little bit scary, I think, for some of the employees, but anyway, he said, “We don’t invest in our employees because they leave.” I said, “Okay, the causation could be reversed. Why don’t we just test it? Why don’t we take a very humble approach and just collect some data and see if it work?

“We know investment is low. Here’s some things we can do: You can hire a part-time career coach to work with incoming employees. You can develop a career ladder so people know where they are expected to go. You could talk about their career development within this division, across divisions of this pretty large company. How do you get to the New York office, the headquarters? How do people do that? You can invest in more professional development so they’re not just stuck with the three weeks of training they got, and then they’re working the phones. Give them more training during the course that year and try to invest in keeping them. You can set them up for health and wellness programs. Think of the whole person development.”

A number of these were actually implemented, and sure enough retention went up. Employee engagement went up. Not everyone wants to stay, and that’s fine for an entry level job, but it really makes significant difference, and then they started developing their own internal talent, so lots of companies I talk about in the book have done this. Goldman Sachs started recently, Goldman Sachs University, to do the same things, and McKinsey has a program where they focus on internal promotions first. Before they look outside for someone, they look for someone inside, and see if they, “Hey, in six months we need a new VP in this division. Who could get some extra training and take that spot?”

I think there’s good reasons to first look at the people that you have around you, and there’s a war on talent, and this book is all about winning that war on talent. As you know, the book starts with some pretty grim statistics on how hard it’s going to be in Western Europe, how hard it is now in Western Europe to find talented individuals, and very soon that will start binding in the US.

I want the best people working with me. I know you do too, so how do I engage those people? I don’t micromanage them. I want to give them the trust they deserve once they’re trained to do what they’re going to do, surely hold them accountable and mentor them and develop them, but let them run. From a leadership perspective, it means I’m spending less time micromanaging every aspect, and I can spend more time thinking about where we’re going, what new markets do we want to go in, what’s our new strategic plan? What partners should I be developing, as opposed to getting involved in people’s day-to-day work lives.

Roger: Paul, do you get respect when you talk to companies? One other major underlying theme that really starts the the book off is that trust begets trust in that if you want people to trust you, you can actually accomplish that by trusting them, but I’m guessing that when you talk about trust to a company, some folks are going to say that, “That may work at X company. That might work at Zappos, but in my company, we don’t have the kind of employees that you really can trust.”

I know for years I owned a direct marking business, and I had a chance to visit some really large, successful direct marketing businesses too to see their systems and whatnot. In some of these places, they had warehouses where they had metal detectors as people left to make sure that the warehouse employees weren’t pocketing anything on their way home, at least nothing that a metal detector would find.

This was really clearly a low-trust situation where the employee cannot leave the building without going through a metal detector, but I would guess that their experience was that when they did not have that in place, there was pilferage going on. I know I experienced in our business. We had a pretty high trust situation until we found that some of our expensive electronic components were going missing, and we had to not do anything as serious as metal detectors, but we did start doing a lot more lock and key stuff with access to those really expensive components. Is it the people in that case or is it … Can you actually change people’s attitudes by your attitude? What if you are experiencing problems where you’re trying to trust your employees, but it’s not working out?

Paul Zak: That’s a great question, and the book has a number of examples of how to do that. The first is that the companies I’ve worked with directly often are under pressure for some reason, and it’s usually one of two types. One is that they’re facing some kind of crisis where they know they’ve got to make change, and that’s almost, as a consultant that’s the best situation to be in because they really want to make change. With the mandate you can really push changes through.

Even those cases, in the book I talk about working with a large Southern US business services company, and working with the executive team for a couple days, and working in strategic plan for these culture changes, and I’m going to take some, sorry to my friends in Texas, another whack at them. It was was another Texan actually in the room who before I started said, “This stuff is all hooey. I don’t care anyway.” Turns out it all worked beautifully, and a year later that guy wasn’t with the company anymore.

Part of it is that you ought to be part of the team. You want to be part of the new program, and you’ve got to fully support it. If you’re not time to jump off the bus or be pushed off the bus. The second kind of company that generally worries about culture that I’ve seen is companies that are rapidly growing. These are the Zappos who have started small with a really cool, interesting culture, and they’re concerned that as they continue to grow, that culture will get degraded somehow.

When you sit down there, and Tony Hsieh who started Zappos has become a pretty good friend, or Chris Rufer who started Morning Star Tomato, when you sit with these business owners who basically brought this baby to life, this is their baby, and they invested time, sweat, and tears, and blood to make it happen, and you say, “This is how your culture is working. This is where it’s not working so well.” It’s like their heads explode because they’ve never had that kind of data. They’ve had impressionistic data from going to different divisions or different locations.

It really gives you something concrete to talk about. Yeah, there’s going to be naysayers, but that’s how I think, as you said, the process should be started slowly. It’s not like we have an off-site, and we’re all going to decide to change what we do every day. It just doesn’t work that way. I think it’s taking a couple whacks at it and then just continuing.

One thing about culture is if you’re changing it, it’s got to be alive. As you know, the brain is a very lazy organ. We accept these default pathways, and that’s the way we want to behave. It takes energy. It takes effort to change those defaults. If you’re going to go from zero to 100, good luck. If you’ve ever been married or had children, you know you can’t change people very much, a little bit but not too much, but you can change the environment that you put people in. When you change that environment, and if you do it in a thoughtful, transparent way, and if you give people feedback on how well they’re doing, there’s a reason for that.

Those building blocks, as you remember, Roger, are ordered in a way, so there’s a place to start. I don’t want listeners to think, “Oh my gosh, this is climbing Mount Everest. It’s just going to be impossible.” Just start small. The nice thing is neuroscience really gives you very precise predictions about how to take those steps to get biggest impact on brain and behavior. It’s baby steps all the way, but as long as that baby continues to walk for a long period of time, it will start to walk, and it will start to jog. It will start to pick up speed, and what I’ve seen is within a year with a committed senior leadership, really transformative leaders, you can have a substantial change in the way people feel at work. You can feel it immediately.

One of the chapters, I’ve forgotten now which one, but it starts with me walking through I think it was this Southern Business Services company with an empty building with cobwebs like, “Oh, let’s go through this building. It’s a shortcut to the meeting where our meeting is.” Like, “Oh, that’s depressing.” There’s an empty building on this big, beautiful campus, and it’s a company that was really a wonderful company, and now actually a … This wonderful transformative leader whose name I’m just going to suppress, but if he’s listening, he knows who he is, really turned this place around.

You walk in now, and you feel energy, and you feel excitement, and you feel like something is happening. I was out there just about six months ago, and the whole place is different. It just has a different vibe to it. It would be okay if we were, I don’t know, we had some kind of ESP and we could measure that vibe, but I’m a boring, practical person. I just need to have numbers. I want to measure what that vibe is. If I get enough information, I’ll find these little pockets of excellence, and I’ll find places that aren’t doing so well, and as you say, just copy the places the places that are doing well and intervene in the places that aren’t doing so well step by step.

Roger: Your empty building there reminded me of some other little sort of tangential reference in the book about the effect of physical spaces on humans and perhaps their neurochemistry. I think it was maybe some work that we were doing with Herman Miller, and more than I bet it’s probably 10 or 12 years ago I wrote a blog post on neuroarchitecture and that that was going to be a coming thing. Either I was totally wrong or was still way too far ahead of my time because it hasn’t happened yet. What’s your take on the sort of intersection of architecture and the way our brains work?

Paul Zak: That’s a great question. That was a study we did with Herman Miller. It brings us back to dogs, so we’re coming full circle. I have a six-month-old German Shepherd puppy, and I can’t believe he hasn’t started barking, so if you hear barking, that’s this dog. He’s going to bark because he’s in the back yard, and he is away from his troop. He’s away from his tribe, his pack.

We often do the same thing with people at work. We put them in these little, teeny cages called corrals or “offices,” partition spaces, and that’s not what social creatures do. We want to congregate. What we do with Herman Miller’s we looked at less versus more open spaces. We didn’t look at closed space with no windows. We looked at half walls versus no walls, and measured brain activity, took blood, and we videotaped people working. It’s a ton of work.

We found that in these open spaces where there is more movement, there is more noise, people actually are more innovative. We measured innovation by having people do new tasks together as a group. They recovered from the stress and worked faster. They were more relaxed during work. They were happier. I think it’s getting back to our evolutionary roots. We like to be in sort of open plains, not too open. A wall or two is not bad to keep out the weather.

I think congregating is fine. In fact, we talk in the book about something a lot of companies including Zappos has done which is create nooks for people to hang out. Have a little corner where you’ve got, I don’t know, sodas and coffee and some healthy snacks, and have wireless in the office. If you want to work on the couch, great, and you might bump into some folks. Put in a ping pong table.

I was meeting with Zappos about a year ago with a guy who runs their culture team. I don’t know about you, but I have a lot of energy, and so I can’t sit still for that long. An hour is a long time because I’m always busy and doing things. I saw this ping pong table, and I’m like, “Hey, can we play ping pong while we keep talking?” He’s like, “Yeah.” We sat there for an hour and talked and played ping pong. It’s not the ping pong; it’s just an opportunity to stand up, to move, to do these things that we are really built for. We’re not built to sit on our butts for hours and hours.

I think it stimulates thoughts, and it also brings us kind of joy to the workplace where we did some cool stuff, and we played ping pong for an hour, but it’s all good because things got done.

Roger: That’s great. Maybe there’s the topic for your next book, new architecture. Hey, Paul, we’re getting close on time here. Let me ask you one last question. Is it true that you had a voice acting role in The Amazing Spiderman?

Paul Zak: That is a true story, and I’ll tell you how it came about. As you remember, I spoke at TEDGlobal in 2011 in Edinburgh, Scotland. This is a little plug for TED: Nice thing that TED conference does is they have an app, and they match you to 10 people you should meet while you’re at TED, 10 other attendees. It was a total life-changing experience to be on the big TED stage and speak.

Anyway, one of the people I met become a wonderful friend named Wendy Hoffman, and Wendy is a professional who creates the background voicing for movies. When they film movies, only the actors are actually speaking when they film it, and the people in the background are actually just moving their mouths, and they’re not making sound because you want to get really good sound.

They go in the studio afterwards, and they fill in all that background voicing, and the next thing is the people like Wendy who do this, you want to actually create authentic background voices. You should know what city you’re talking about. There was a couple of scenes in The Amazing Spiderman where they’re in a neuroscience lab, and so myself and another neuroscientist named John Rubin basically we’re on a sound stage in Century City, California, and we were making up dialog as we’re walking along, as if the background characters are walking along, the same way from microphone A to microphone B.

Anyway, that one, and I did the 10-Year Engagement, which I think was kind of a flop movie. Also there was another neuroscience scene. It’s a really weird thing to be in a room full of professional voice actors who can do every voice on the planet, teenage girl from New York to old black guy playing jazz in New Orleans. I can only do one thing. I can just talk, so I just feel bizarre. Anyway, it was a real weird pleasure. Actually I did that on my 50th birthday, and it was the best birthday gift I ever got, so thank you to Wendy Hoffman.

Roger: That sounds really cool. Amazing attention to detail to some real neuroscientists to do neuroscience dialog as opposed to just giving it to whoever happens to be standing around saying, “Here, read these lines into the microphone.” That’s great. Let me remind our audience that we’re speaking with Paul Zak, neuroscientist, oxytocin expert, and the author of the new book Trust Factor: The Science of Creating High Performance Companies. If you want to build a high performance organization, Trust Factor is your blueprint for culture development. Paul, how can our listeners find you online?

Paul Zak: They can find out more about me at pauljzak.com. You can follow me on Twitter @pauljzak. Lots of free resources about the culture tools, and you can try our survey at ofactor.com. Poke around and download all the free stuff, and help yourself.

Roger: Great. We’ll have a link to those places along with any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. Paul, thanks for being on the show, and hope we get to talk again soon.

Paul Zak: You’re the best, Roger. Thank you so much.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.