How can you avoid being an entrepreneurial failure? Most startups don’t achieve success, but author and entrepreneur Gabriel Weinberg has decoded the pattern followed by the most successful startups.

How can you avoid being an entrepreneurial failure? Most startups don’t achieve success, but author and entrepreneur Gabriel Weinberg has decoded the pattern followed by the most successful startups.

Gabriel is a successful entrepreneur in his own right. He’s the founder of the DuckDuckGo search engine, notable for the fact that it doesn’t track its users. He had the chutzpah to take on Google and Microsoft in this hotly contested space and has seen traffic grow exponentially.

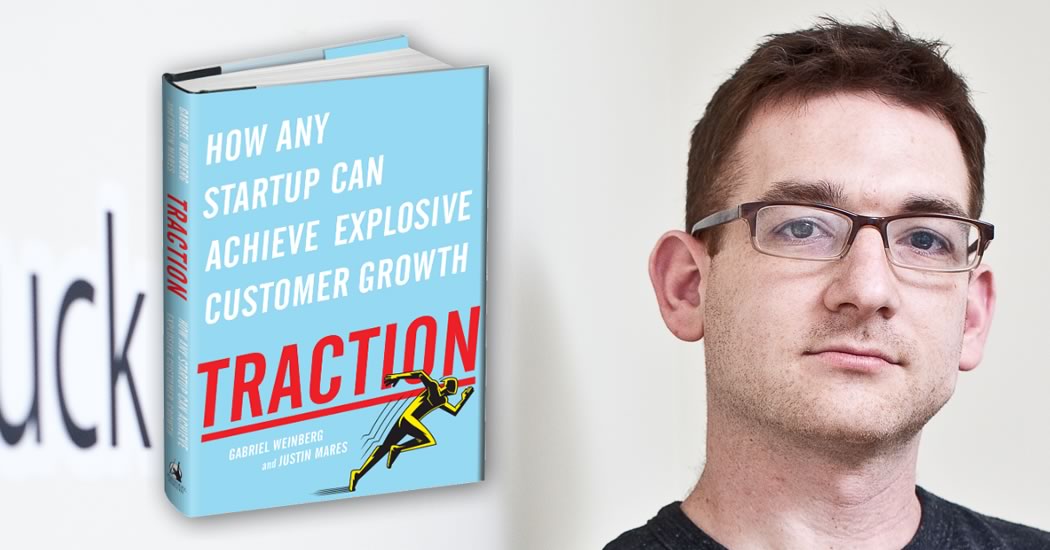

In the midst of starting a high-growth search business, Gabriel found time to write a book focused on why a few startups succeed and why so many fail. Based on his experience with DuckDuckGo and other ventures, and after interviewing many other entrepreneurs, Gabriel co-authored Traction: How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast, and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why Gabriel decided to start a search engine.

- How his multiple side projects merged into DuckDuckGo.

- The key differentiator between DuckDuckGo and Google.

- Why privacy can improve your search experience.

- The concept behind the nineteen traction channels.

Key Resources:

- Connect with Gabriel: DuckDuckGo | Traction | Twitter

- Amazon.com: Traction: How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth

by Gabriel Weinberg

- Kindle Version: Traction: How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth

by Gabriel Weinberg

- Amazon: Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal

- Brainfluence Ep #83: Today’s Hottest Lead Gen and Subscription Techniques

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. I’m super excited to have today’s guest with us and I know you will be too. He’s a successful entrepreneur that has been building a business that competes directly with one of the most powerful companies in the digital world. He’s also an accomplished author who self-published a book that sold so well it’s now been picked up by a major publishing house. And, he’s got a couple degrees from MIT.

Enough of the teases, I’ll tell you we’re speaking with the founder of DuckDuckGo, the upstart search engine that is experiencing tremendous growth despite the fact that Google is the dominant force in that space and that Microsoft is a distance second. He’s the coauthor of the best-selling book, Traction: How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth.

Welcome to the show, Gabriel Weinberg.

Gabriel Weinberg: Hi, my pleasure to be here.

Roger Dooley: Well it’s great to have you here, Gabe. I think probably few of my listeners know that my entry into the digital space was actually via search a long time ago. This was back in the late 90s before Google was even around. In those days, AltaVista, Excite, and Lycos were the dominant players. I had a partner in another business who launched an ecommerce site that was struggling to get traffic so I sort of learned SEO from scratch by experimentation and by networking with other people in the space.

Those were the days when on-page factors were about the only factors. You could rank number one if you just knew the right formula for … Gee, repeat a keyword twice in the title.

Gabriel Weinberg: Keyword stuffing.

Roger Dooley: While not so much stuffing. This was like stuffing was still used but it was slightly post-stuffing, where they said, “Oh boy, people are stuffing keywords.” When I was doing well you had to know how many times to repeat it in the title and the body, get it in the right place, the right position, and so on. If you had that formula, you could rank number one for anything in like 48 hours.

Of course, those days are gone and that’s probably a good thing because not everyone would use that power for good. Actually, of course, Google came along and reshaped that market. I guess I was lucky because I was working on links before they were popular. So when Google began taking share, my stuff continued to do reasonably well.

I’m curious, what made you think it was a good idea to launch a search engine when even big-budget efforts like Microsoft really couldn’t make headway against Google?

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, so the real answer is I wasn’t necessarily trying to launch a search engine [laughs]. I had sold my previous company and was really trying to figure out what to do next. One of the things I learned in that whole experience was I wanted to do something that I could work on for about a decade or more because that’s kind of how long startup success takes. So I wanted something that I was really fundamentally interested in.

I spent a year or two just starting side projects and discovering really what I was passionate about, and a bunch of those were search related. So not setting out to build a search engine, I set out because I was frustrated with my own Google results in 2007. Namely, they had a lot of spam and content farms in them. I don’t know if you remember those days.

Roger Dooley: Oh, yeah.

Gabriel Weinberg: Basically, there was a resurgence of that kind of stuff around the mid-2000s.

Roger Dooley: Oh, right. I mean, between the scrapers and the content spinners and everything else. It was really terrible.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, it was all over the place. Not only that, it was kind of very identifiable as a person. So I figured you could identify it as a computer pretty easily. So I built a side project doing that. Then also I realized that I kept going to the same sites over and over again to get answers, like IMBD or Yelp, when they were coming on, and eventually YouTube. And said, these really should be instant answers. I really shouldn’t have to go these sites.

So those two projects—and there were a couple other ones I was messing with—and realized I’m really excited about this area and if I combine a few of these, they could be maybe a more compelling search experience. And for various reasons, Google wasn’t doing much in these areas. That was really the crux of it. So it was really personal interest and I launched it just to see if there was interest, and there was interest.

People were frustrated in similar ways that I was and were also just, I think, Google had been already dominate for six or seven years and there were these kind of rumblings of interest in other things. That’s, I’m sure, one reason why Microsoft jumped in. So the short answer is: I didn’t set out to build to take over search or anything. I really just set out to improve my own experience and then I kind of backed myself into the business.

Roger Dooley: Ultimately, privacy became sort of the key differentiator with DuckDuckGo. How did that come about?

Gabriel Weinberg: It came about initially from talking to users. I had just started it, like I said, as a side project and launched it with these instant answers and spam in mind and also finding better links.

Then almost immediately, I got questions around search privacy and I really had my ear toward the ground in terms of traction and figuring out what I could do. Because as you said, Google is dominant and I really wanted to know what would motivate people to switch search engines and so I was trying all sorts of things.

My thesis for the company was more like, let’s do things that make a better search experience, that Google won’t do easily for non-technical reasons, but maybe for other reasons. So I got these questions around search privacy. I hadn’t thought about it before. I do have a degree, like you mentioned, in technology and policy. So it’s not like I was new to these issues but just hadn’t approached them with regards to search privacy.

So I did my own investigation. Found that if you think about it, it’s really the most personal data on the internet. You kind of think about what you post to social media, I hope [laughs]. But, you do not think about what you type into your search engine.

So you type in your medical, financial problems, without really thinking about it. And increasingly, this information was getting handed over to governments and marketers. Now, like years later, these things follow you around the web for months, you know? Which is both creepy and annoying.

But what I realized was you don’t need to track people to make money in web search because the money is made just by typing in a keyword and getting an ad against that keyword. So if you type in “car,” you get a car ad. So really it’s the better search experience not to track people. Let alone you get all the privacy benefits, but it’s just better for people.

Roger Dooley: So are you able to deliver retargeted ads if you don’t track yourself? Because it seems like retargeting is a fairly lucrative area for firms that deliver advertising and certainly for Google. Will people see retargeted ads from a third party or basically would that compromise their privacy at DuckDuckGo?

Gabriel Weinberg: It compromises your privacy.

Roger Dooley: Right, okay.

Gabriel Weinberg: You will not see retargeted ads. But the beauty is on the search engine, it doesn’t matter because you type in “car” and you get a car ad and the retargeting is just less relevant.

The reason Google does that is because they run ad networks all around the web, as you know. So when you go to millions of other sites, people don’t realize, but they’re often seeing Google ads. So you get that retargeting effect where these ads follow you around the internet. But if we just run a web search, we don’t need to do that.

Roger Dooley: Right. Your most relevant ads would probably be … the place where retargeting might improve your monetization would be if people were doing searches that were hard to monetize or had just very poor monetization prospects. In those cases, maybe a retargeted ad would have a little bit higher revenue but that’s great.

I think these very targeted ads are one of those things that on the one hand it’s a plus. Like if you read a magazine, like a camera magazine, it’s full of camera ads, which you don’t mind because you’re interested in cameras and you want to see these ads. But at the same time, when you look today at a briefcase online and for the next three months you’re seeing pictures of that briefcase even though you bought a different one, that really drives you crazy.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah. It drives people nuts. That’s just one kind of harm. There are deeper harms that people don’t realize are going on, besides the government surveillance. Generally on retailers now and increasingly so, you’re getting charged individual prices based on what they think you’ll offer or could pay.

So you can be sitting next to someone and go to the same website, look at the same product, and see a different price. I think that fundamentally rubs people the wrong way. Then even more subtly, they may show you different related products and other products based on what they think you may be more likely to purchase. I think once people start to realize that, they want to reduce their footprint.

Roger Dooley: Right. That makes a lot of sense, particularly if for some reason vendors have you pegged as a high spender or somebody who is not too concerned about price. That would be certainly a negative to everywhere you go hit the high end of the price range. Although, it seems like at some point you’d run afoul of price discrimination laws, but I guess that’s yet to be tested.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, there’s two responses to that. One, kind of funnily, the first-order effect of this was companies just charging all Mac users more prices. Orbitz was originally found to do that. Then Staples was charging just people in different zip codes different prices. So that’s already just lumping whole large groups of people into the wrong buckets which is kind of interesting.

Roger Dooley: I recognize that your objection isn’t to knock off Google as the number one search engine, at least not in the next year or two, but it seems like the biggest thing that they have working for them is the power of habit.

My friend Nir Eyal wrote the book, Hooked, which is about building habit-forming products. He uses Google as a prime example of a company where the habit is so ingrained that it’s very difficult for competitors to make headway, and that is part of Microsoft’s problem. Even if Microsoft has effectively solved the search quality issue and their results are comparable, people still keep using Google. If you’re going to check somebody out, you don’t “Bing” them, you Google them.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, there’s two aspects to that. One, it’s ingrained as a word, which can’t go away, like Kleenex kind of thing.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure Google has mixed feelings about that. On the one hand, their IP attorneys probably are sending out cease and desist letters. On the other hand, the marketing folks probably like being the default word.

Gabriel Weinberg: Exactly. But to your deeper point, there was no real pain point with people. Some of the habit is they’re satisfied with the Google experience, so another search engine, to get people to switch to you, you really have to differentiate in some way. So privacy is one way that we differentiate and that really resonates with a large percentage of the population.

But there are other ways that we also try to differentiate in. For example, design. Just the experience on DuckDuckGo is kind of more fun. People who connect with it feel like they’re part of something a little more that is less businesslike than say Google is. So there are other aspects to differentiate.

But other companies have struggled in this space by either trying to differentiate too much, where it’s hard for people to actually switch because there’s too much of switching costs, so just mentally figuring out how to use it. Or, they’re not differentiated enough, where they look such like Google that there’s no incentive for them to switch.

Roger Dooley: Yeah and certainly some aspects of being a rather Google-like, at least the results pages have been at times.

You mentioned delivering more information than search results. It seems like that’s definitely the direction that Google is headed in. A few years ago, if I searched for “college football schedule,” which I frequently do on a Saturday morning just to see who’s playing when. A few years ago, I would have gotten a link to ESPN or perhaps some kind of college sports site.

Now, Google delivers me a list that I can expand of all the games that are being played. They’ve basically eliminated the need to leave their page to find out that information. You mentioned DuckDuckGo doing that, do you think that’s really the future of search? Being more of an information provider than a search results provider?

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, I do. I call it “answers.” When people are searching, they’re really looking for answers. They’re not looking to click on a webpage. To the extent that the search engine can kind of broker those answers, I think they’re going to be better positioned.

Especially if you think on mobile, where it’s more annoying to go to sites, and answers can be more effective on that smaller real estate. Now our approach has been to differentiate, has been an open approach to answers, where we really have open sourced the entire thing.

Really any DuckDuckGo user can suggest answer sources and even code them and put them on the site, as opposed to the closed approach other engines like Google have taken where they’re buying data and doing it all algorithmically in house. But, yes, I think overall, answers is the future.

Roger Dooley: That can lead us into our discussion of Traction because if you’re highly dependent on SEO and organic search traffic as your traction channel, perhaps a few years down the road that may not be a very viable strategy.

First of all, congrats on the Portfolio Penguin deal, Gabe. It certainly validates the concept. Although, I think the sales of the self-published version probably validated the concept pretty nicely too. Did you have publishers beating down your door after the first version took off?

Gabriel Weinberg: Thank you, first of all. Yeah, so essentially the whole publishing industry is super interesting and in flux at this point but I don’t think they necessarily know unless you talk about it. So I eventually put out a post about how we got traction for the book, explaining how we used basically the framework of the book. I mean, exactly we used the framework from the book to get traction for Traction and how we did it and how many copies we sold and all that kind of stuff.

At that point, the eventual editor that we went with from Portfolio Penguin did reach out and that’s how we actually met. At the same point, we were also seeking publishers just to float to see if that was going to be a next step for the book. So it all happened kind of at the same time. But yeah, people reached out to us.

Roger Dooley: Right. That’s great. I noticed that you publish quite a bit at Medium. Do you like Medium as a medium?

Gabriel Weinberg: Well interestingly, I had my own blog on Movable Type actually [laughs], an old …

Roger Dooley: I’ve used that. Not in some years but yeah, I was a Movable Type user for a while. Really, for its time, it was pretty good.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, right. So I kind of got onto them, maybe 2003. Then in 2006, I established my own personal blog again, under my own domain on Movable Type and I used it really up until this year. I decided in this next round of trying to publish the book that I would recast that and try some new things. So just this year I moved to Medium and really started testing there.

I also tested posting on LinkedIn a bunch, or a bit, and I’ve really enjoyed the Medium experience honestly. I think the idea that the publishing platform has a built-in network is a good one because I found over time that publishing my own blog, you know, people stopped using RSS, right? And they stopped coming back to your site directly and people had spent more and more time on platforms. So you really have to go to those platforms with your content.

Roger Dooley: That makes a lot of sense. So back to Traction. You’d think you’d have your hands full with a startup but I guess I’ve already suggested maybe you were crazy to start up a search engine in the face of Google. Isn’t it kind of crazy to decide to write a business book while you are in the middle of, really, a significant startup? [Laughs]

Gabriel Weinberg: Probably [laughs]. It did take me many years to get it out the door. So I started working on it in 2009. What happened really was I sold my last startup like I mentioned, and then I ended up doing DuckDuckGo. Then I tried to get traction for DuckDuckGo in the same ways I did my last startup and it just did not work. I was not finding success that way.

So I went out to figure out if there was a framework to get traction and I found that there was not. Then I literally started researching and interviewing and jumped into figuring out how other people were doing it and hit upon the framework that we use in the book called Bullseye. Then was like, “Oh, wow, this is really a need here.” I advise startups, I do angel investing, and everyone struggles with getting traction. Then my startup took off. It started taking off because I applied the framework and it worked.

And I didn’t have any time to write the book and it got shelved for like two years. Then eventually I found a coauthor to help me do it. Then it literally took us another two years to get out the door. So, yeah, it was crazy but also, I took a very long time because I didn’t have a lot of time to work on it.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, you validated the concept though by the success of DuckDuckGo. That gave you your built-in credibility and example right there.

You know what I really like about the book, Gabe, is how practical it is. It isn’t a lecture on the theory of startups. It’s really more like a hand-to-hand combat guide for entrepreneurs. Let me summarize what I think the key premise is: Just about every startup has a product and probably in a lot of cases, the product is filling some kind of need in the marketplace. But what most startups lack, or at least many startups, are customers.

If they can’t build their customer base quickly enough, then the product itself doesn’t really matter. It’s going to die because they’ll run out of money or they’ll lose interest or lose people or whatever. If you want to succeed as a startup, you should be spending as much time in those early days in developing your customers, figuring out your channels, and so on, as you spend on the product itself. Is that pretty close?

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, that’s an excellent summary. Thank you.

Roger Dooley: Well you list nineteen traction channels. We don’t have to go through all nineteen, but explain the concept of the traction channels.

Gabriel Weinberg: These are really all the ways companies are out there getting traction and it’s really meant to be an exhaustive list. So we mentioned search engine optimization at the beginning, that’s one of the nineteen channels, along with things like trade shows or search engine marketing or offline ads, like billboards. So we literally went through and identified every single way.

We found that really companies of all kinds and phases, so consumer or business, or online or offline, were using each of these channels to get success. The other thing we learned was that in each growth phase … so if you identify a goal, like an inflection point for your company or project and you achieve that goal, or we saw startups achieving those goals, there was usually one dominant channel that was driving the growth there. So you end up with this universe of nineteen and one thing is successful.

And the third kind of key learning was it was often an underutilized channel for that industry. So everyone in the industry is using search engine marketing or SEO, it’s very competitive and hard to get success there. But if you go in another direction, then you figure out how to use, like speaking engagements, to get traction. You have an open field there as a startup.

So the game or the practical piece really becomes narrowing down that nineteen and to find that one channel that’s going to get you to grow. That’s why we use this bullseye metaphor, because you’re really trying to hit the center of the target. The bullseye, which is that one channel.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I guess probably a lot of entrepreneurs try too many channels at once or they just use sort of a scattershot approach. Your bullseye concept sort of narrows the field down to the one or two that are actually going to work by sort of a simple process of winnowing. Why don’t you explain how that works from the outer circle down to the bullseye.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, it’s really just a three-step process and it is a very simple process but people mess it up, including myself [laughs]. Because it’s a tricky process. The first step is really to brainstorm. The three steps are to brainstorm all the channels, run a few tests in parallel, and then try to focus on the one that’s working.

The way this kind of gets messed up—in a couple ways. The first is people don’t necessarily setup goals. So really step zero is to set that hard number you’re trying to reach. I messed this up starting DuckDuckGo. Then the reason you want to set that number is all your marketing activities, all these tests your running on these channels, are measured against that goal.

So if your goal is 100 customers but you really figure out that SEO is only going to scale you to ten customers in the best case, you really shouldn’t waste time there. Because you’re never going to reach your goal, which is literally the mistake I made with DuckDuckGo. So you end up brainstorming tests that you can run in each of these channels.

These are supposed to be cheap and fast tests, like no more than a month, no more than $1,000. You’re trying to discover a couple things. You’re discovering, how scalable is that channel? Can it reach that goal? How costly is it? How much does it cost to acquire a customer? And also really, are they the right customers? Are they converting and sticking around in the way you like?

Then if you think about tests in that way, you’re thinking about, “Okay, if I’m going to go to a trade show, what is the best trade show I should go to?” If I’m going to go speak in front of an audience, what is that best audience? I’m going to advertise on a search engine, what keywords would I use? In that brainstorming, you then look across all your tests and you say, “Okay, well, these three are the most exciting tests that I think could validate whether that channel could reach my goal.” Then you go run them in parallel.

Hopefully one of them actually proves out your assumptions were valid and that you do think if you double down on it, it could reach your goal. Then you really focus on it. You’re still testing at that point but you’re testing for strategies and tactics within that channel that you think will again be underutilized and kind of really make your growth explosive.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think it’s important to question your assumptions about what’s going to work. I know my own experience includes, strangely enough, more than one failure.

Years ago, I started a magazine called Electronic House, which is, and fortunately, it’s still be published, although I haven’t been involved in the ownership of it for most of its life. But when we created this concept, we said, “Okay, well how do magazines promote themselves?” Well, they used direct mail, this was pre-digital, pre-internet marking channels, and so on. You know, if you’re Condé Nast or somebody, you do direct mail.

So we followed that model and it was incredibly expensive and incredibly ineffective for what we were doing, which used up a lot of the money that we’d allocated to getting it going. We used PR and we got a mention in Time magazine and some other great publications, and this was the holy grail for us. Like we were sorting of waiting for all the inquiries and subscriptions to start rolling in [laughs] and that never happened.

What did work was John Dvorack, who was then a tech columnist at InfoWorld, mentioned the magazine in an offhand manner in one of his columns and that produced like a thousand or two thousand inquiries. So had we applied, we obviously didn’t have the same nineteen channels back then pre-internet, but had we applied the logic that you describe in Traction of doing some small tests, seeing what works and what doesn’t, and focusing on those things, we probably would have had a much more successful start.

As it was, we ran with it for a few years and then eventually sold it to somebody who was more focused on the publishing industry and they’ve done a nice job with it since. And of course that market, we were kind of early for the market too, which has developed over the years. But I can definitely see how applying the principles in Traction would have probably saved us a lot of money and perhaps made that a more successful venture for us.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yeah, in retrospect, me too [laughs].

Roger Dooley: Yeah, hindsight is great, isn’t it?

Gabriel Weinberg: I didn’t realize this until later in my career too. So I wish I had thought of some of this stuff beforehand.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well, it’s out there now for all the entrepreneurs and would-be entrepreneurs in the audience so they can profit from your mistakes and my mistakes.

So last week’s guest here was Poornima Vijayashanker, who was the lead developer at Mint, and you used Mint as an example in your book. My friend, Noah Kagan, who’s here in Austin was their marketing person. What was the channel he eventually found traction in for Mint?

Gabriel Weinberg: Mint was really a great example and one of the early interviews we did. We actually talked to them multiple times, it really helped validate and formulate this process. They did, and Noah particularly, did a great job of setting that initial goal. They initially wanted to launch at 100,000 customers in the first six months. He was very quantitative, built a spreadsheet, and ran tests in a bunch of channels, to really validate if they could reach that goal.

They ended up focusing initially on targeting blogs, very similar to what you mentioned just now and success. Just trying to get some of these financial bloggers … Mint, as your listeners heard from last week, is this financial tool and there were a lot of financial bloggers who are very personal bloggers who didn’t actually have any advertising on their site. So one tactic they kind of uncovered in this quest for underutilized tactics is to go sponsor blogs that didn’t even have ads. They paid them small amounts of money to put this Mint badge on their website and got tremendous success that way.

They also creatively developed this process, which is now more common for startups, it’s kind of like a velvet rope strategy, where they would give people who would share about Mint kind of to jump the line in the beta and get access to Mint first before it came out. They got I think about half of their goal, about 40,000 pre-launch signups just with focusing on targeting blogs.

Then once they launched, they had a good story and they really switched. They did another ad test but they switched channels to PR and that’s really another story in the book and one I’ve learned at DuckDuckGo, is that unfortunately, channel strategies saturate and you have to switch and basically run this process again with a new goal in mind.

Roger Dooley: Right. Probably the one key takeaway is that if you think of this strategy as being the right one because your competition is doing it, then it’s probably not the right one.

Gabriel Weinberg: Yes. You want to kind of zig while they zag, if you will.

Roger Dooley: So let me remind our audience, we’re talking with Gabriel Weinberg, founder of the DuckDuckGo search engine and coauthor of a book that I highly recommend to all entrepreneurs, Traction: How Any Startup Can Achieve Explosive Customer Growth. How can our listeners connect with you and your content online?

Gabriel Weinberg: You can check out the book at TractionBook.com. I’m best reached at Yegg, which is on Twitter, @Yegg.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will have links to that and any other resources we mentioned on the show notes pages for this episode at RogerDooley.com/Podcast. We’ll also have a text version of our conversation there as well. Gabe, thanks for being on the show.

Gabriel Weinberg: Thank you, it’s been my pleasure.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.