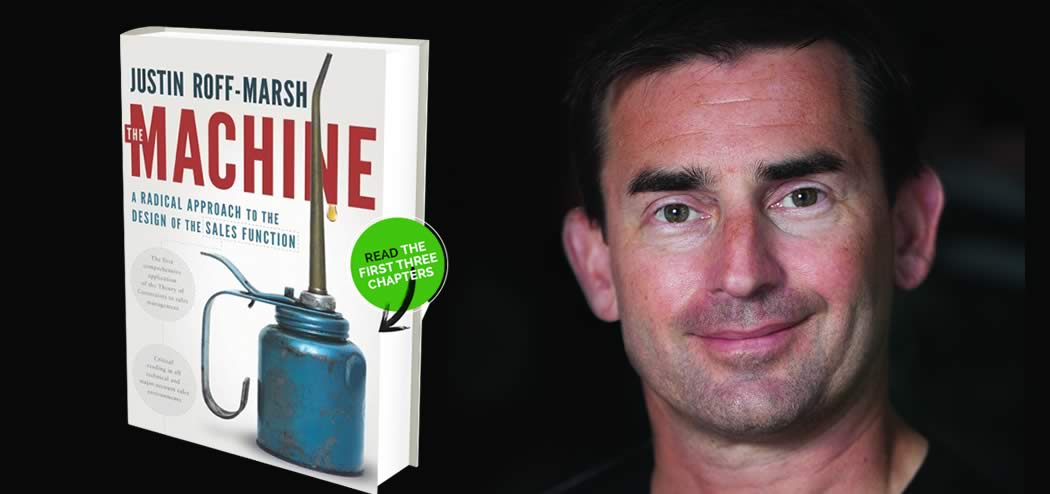

This week on Brainfluence Podcast, I am joined by Justin Roff-Marsh. Justin is the founder and President of Ballistix and author of the new book, The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function.

This week on Brainfluence Podcast, I am joined by Justin Roff-Marsh. Justin is the founder and President of Ballistix and author of the new book, The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function.

Justin is a thought leader in the field of Sales Process Engineering, a radical new approach to the management of the sales function. He is also the editor of the popular Sales Process Engineering blog.

Over the past decade, Justin has presented Sales Process Engineering at events to tens of thousands of executives around the world. He has been a guest speaker at many industry events, conferences, and association meetings, and has facilitated Solution Design Workshops for hundreds of companies in a variety of industries throughout North America and Australia.

Justin joins me today to share his incredible journey that led him to become a sales guru, founder, and an author. Listen in as Justin talks about his predictions in the world of sales and shares his tips for creating a powerful sales team. So turn up the volume and get ready to take notes, because you are not going to want to miss Justin’s strategies for building a sales machine that will ensure your company’s success for years to come.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why Justin made the leap from engineering to ballet to sales.

- The real reason that customers stay loyal.

- Justin’s prediction on the future of sales careers.

- The perils of pushing your sales people into becoming thought leaders.

- The 2016 sales team model.

Key Resources:

- Amazon: The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function

by Justin Roff-Marsh

- Kindle Version: The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function

by Justin Roff-Marsh

- Connect with Justin: Sales Process Engineering | Ballistix | Justin Roff-Marsh | LinkedIn | Twitter

- The Machine by Justin Roff-Mar (First Four Chapters)

- Duct Tape Marketing

- Amazon: The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement by Eliyahu Goldratt and Jeff Cox

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week has a unique background. He’s a self-described lifetime science nut and he turned down engineering school to study of all things, ballet, in college.

Among other things, he spent seven years in direct marketing. He’s an expert in a discipline called the Theory of Constraints. He’s a thought leader in organizing the sales function in a scientific way, SPE, short for Sales Process Engineering.

He’s the founder of Ballistix, a firm that’s been around for 13 years that builds and supervises sales operations for clients. His newest book is The Machine: A Radical Approach to the Design of the Sales Function. Welcome to the show, Justin Roff-Marsh.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Hey, Roger. Nice to be here. Thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley: Great. You don’t sound like you’re from around here. What’s your origin, Justin?

Justin Roff-Marsh: I was born in the UK. I grew up in Australia. So from the age of seven to the age of—I don’t know—forty I guess, in Australia. Then I moved to Los Angeles about eight years ago.

Roger Dooley: I still have a couple of continents left to cover I guess. I have to ask you about your ballet and background and the transition to the world of business. Here’s an opportunity, Justin, where you can insert some bad jokes like keeping people on their toes and being fast on your feet and so on. How did that work out?

Justin Roff-Marsh: Well, I’m an Aussie so none of my jokes are show appropriate.

Roger Dooley: Aw, well. Okay.

Justin Roff-Marsh: I guess the ballet story was I was an electronics nut all the way through high school. I think by the time I got accepted into engineering school, I was pretty much done with sitting in front of a soldering iron.

At school, I’d been developing an increasing interest in sport, which was probably driven to some extent by a desire to be more socially adept and in particular to be able to pick up girls. So I think that the attraction to ballet was that it appeared to me to be the most difficult of all sports. I always approached it as a sport. And that’s one of the reasons why I quit, apart from the fact that you can’t make any money and it’s a terrible lifestyle.

I think that the best dancers don’t actually approach ballet as a sport. They approach it as an artistic endeavor. I was a pretty good, what’s referred to as a technical dancer. In ballet, it’s almost an insult to say someone’s a technical dancer. Because it means they can spin fast and jump high but they’re not a good actor.

Roger Dooley: It’s sort of like calling a football player, “He’s a really good athlete,” implying that the higher-level skills aren’t necessarily there but he’s fast or strong.

Justin Roff-Marsh: They’re a mindless brute. So that was the story there. I think that by the time I decided to quit the ballet—so I danced at school I guess, a couple of different schools full time for almost four years. Then when I quit, I didn’t really have a skill. So I went into sales. That’s how the sales things happened.

I started off selling insurance. I was initially a terrible salesperson because I really didn’t have fantastic people skills. But the thing about people skills is that people aren’t that difficult. Or at least the people skills aren’t that difficult to master.

I think a lot of people who are introverted are not interested in developing people skills. For me, I kind of approached it like learning calculus. Compared to calculus, people are simple creatures. Certainly at the superficial level.

Roger Dooley: Some might disagree with that, but the basics perhaps aren’t that difficult to master.

Justin Roff-Marsh: I mean if you’re a salesperson, I was selling insurance, you interact with people at a fairly superficial level. So at that level, it was relatively easy.

What I discovered is that with skills in sales, you can progress incredibly quickly because most people don’t have skills. They maybe have some natural talent but very few people develop skills. So I think I went from being a beginning salesperson to earning a lot of money.

Then I took a step backwards income-wise by getting into management. Before long, I was running a team of 100 salespeople in the insurance industry. At that point, I realized I liked this business thing. I liked the capitalism thing. But running a team of 100 salespeople in that industry was not a good career.

To give you some idea, in my last year working where I worked, we recruited about 450 people to maintain a team of 100. So it really was a boiler room environment and I was…

Roger Dooley: Tough to manage with that kind of turnover.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Exactly, exactly. Really, in that industry being the top salesperson really means you end up being a recruiter because that’s the ultimate sales challenge, which is a sad indictment on the industry.

Roger Dooley: I’m also reminded of the companies that take their top salesperson and make them the manager. Then he or she proves to be not only a fairly inept manager but they killed off their best salesperson.

Let me ask you, Justin, is sales a dying profession? These days, there’s so much emphasis on digital interaction and automated systems and self-service and so on. Is there a future in sales?

Justin Roff-Marsh: It depends what you mean by sales. Sales to the extent that most salespeople do it is absolutely a dying profession. As I travel around and meet with organizations in a whole range of different countries, what I end up discovering, and it’s pretty easy to see, is most salespeople spend most of their time managing transactions, not actually selling.

So most salespeople spend a good percentage of their time processing transactions that probably would have come in if they were on vacation, performing customer service, and so on. If you define sales as somebody who rings a cash register, then absolutely, sales is a dying profession. Amazon and the like will kill it.

The reality is I think for most of us who live in the western world, if we want to buy something and we want it delivered quickly and we want to be confident that it will be priced well, delivered fast, without errors, then Amazon is our first choice. I mean, I think most people will even pay a slight premium to buy from Amazon because of the level of confidence we have in them, both their delivery ability and the customer service they offer if something goes wrong, which it rarely does.

Roger Dooley: Right, that’s absolutely true. I know in Texas a year or two ago we had in essence what was an eight percent price increase by Amazon because they began collecting sales tax. I found that my shopping patterns really didn’t change very much because of that even though now they were somewhat higher than other competitors who did not have that particular issue. You’re right, it’s the certainty and the smoothness of the transactions.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Yeah, that’s loyalty that we’ll pay a premium for. If you look at the loyalty that salespeople typically claim that they have engendered I guess in their customers, that’s the kind of loyalty that customers expect a discount for.

In other words, a typical salesperson who says, “My customer’s transact with me because we have a personal relationship.” When you dig beneath the surface you’ll discover that what that actually means is those customers are actually using the existence of a personal relationship to demand a discount.

Now if you change the definition of sales to mean actually selling something, in other words, convincing somebody to purchase something that they wouldn’t have otherwise purchased that we have to presume is in their better interests, then that will never die. Of course, the idea that a machine could do that is preposterous. At least in the next probably 50 years or so.

So what’s happening I think in sales is a bifurcation with the transactional stuff disappearing altogether but with the importance of true salesmanship probably becoming elevated.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I know I started off my career as a sales engineer in a remote office, just a couple of people. We spent all of our time—well, a mix of making some cold calls, writing complicated proposals because it was a large capital equipment type sale. A lot of our time acting as production expediters and just sort of an interface between sort of unfriendly home office and the customer. We even might have had to help collect a receivable every now and then if the accounting department wasn’t able to do that.

If I look back at the time, we were probably only spending just a few percent of our time on actual productive customer contact. I was surprised at one of the statistics in your book was that even today the salespeople average about ten percent of their time selling. I was really surprised that things have changed so little over the years.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Oh, well if you have business listeners listening right now they will be nodding their heads at your description of what it’s like to be a sales engineer because in most environments nothing has changed. It’s exactly the same today.

Now I think what has changed in most environments, there’s an increasing awareness of the fact that change is necessary. So I’m hoping that The Machine comes at a good time.

Roger Dooley: One different perspective on sales comes from John Jantsch of Duct Tape Marketing. He was on the show some months ago. He argued that the role of the salespeople had really become almost more of a marketing role where the salesperson would be more of a product expert, almost sort of like a mini thought leader in a very small space. And would help the customer with applications and would have their own personal reputation that they might build using social media or content creation and so on.

His argument is that in the past salespeople were mainly sort of product experts where they knew more about the product than the customer did. The customer would ask the salesperson and the salesperson would give them product information, specifications, answer questions.

But today, those same customers are getting that information online. They’re able to look at the specifications, download product sheets, and so on. So the informational role of the salesperson is largely done, at least if the customer has half a brain. Therefore, they have to move up the hierarchy of needs and fill a more valuable role. Do you agree with that or would you take a different perspective on that?

Justin Roff-Marsh: I think in certain contexts, in certain environments, that’s probably a reasonable defensive strategy for salespeople. So if I was giving salespeople advice, maybe I would give them that advice. But we advise organizations, not salespeople.

And I would absolutely disagree that it makes sense to build a sales environment where you have salespeople pretending to be marketers because marketing has become so much more specialized today. There’s a requirement for so much more technology. And marketing, like say software development and other fields, has exploded into a whole bunch of disciplines with not a huge amount of intersection between the two.

So the idea that the salesperson can be a marketer particularly in a larger, in a more complex, not larger, but in a more complex environment is just not workable. If you’re working in a very small business selling something very simple, maybe, but why would you want your salesperson to try and—I went to an inside selling conference in Chicago last year. There were a number of people advocating that your salespeople should—and HubSpot did too—that salespeople should be thought leaders and have their own blogs and tweet and so on.

In the environments that our clients build, the general expectation is that salespeople will be salespeople. If you’re employing people and paying $100,000 or $150,000 or $250,000 for them, what will you really want them for? It’s not their blogging ability. Because the reality is they’re probably not good at that.

What we want them for is their ability to sell. Their ability to stand at a whiteboard in a boardroom with a fist full of markers and sell a skeptical audience a radically new concept. That’s the really difficult skill that organizations are and should be prepared to pay a premium for. Not blogging.

Now if I was going to have somebody in my organization blogging, I would want somebody who truly was a thought leader. That person would probably not be a good salesperson.

Roger Dooley: Right. I guess there’s a tension too between what’s best for the individual and what’s best for the company because as an individual salesperson establishing a personal reputation that extends beyond even the company itself can be a good thing. But that’s not necessarily what the company is looking for with having a bunch of lone wolf salespeople out there who are all establishing reputations themselves.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Yeah, but even my selfish perspective as a salesperson, if my personal reputation outshone the reputation of an organization that I was considering working for, then why the hell would I work for that organization in the first place? Why wouldn’t I go into competition for them? So if I was considering, not that I ever would, going and working for somebody else, I would want to work for an organization that was cleverer than I was.

Roger Dooley: That makes sense.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Yeah, I mean if I had a choice between working for Google where I’d be a nobody or working for some organization where I would be a shining luminary, a bright light. Then I would absolutely go work for Google or Mackenzie or whatever the case is.

I think in the short term there’s probably an upside with that approach for salespeople. But in the long term what’s best for the organization tends to be also what’s best for the team members.

Roger Dooley: So you refer to the Theory of Constraints quite a bit. Can you explain what that is and how it applies to the sales process?

Justin Roff-Marsh: About twenty years ago an Israeli physicist, Eliyahu Goldratt, wrote a book called The Goal. It’s pretty hard to find anyone in a manufacturing environment, certainly in the U.S. who hasn’t read that book. It had a profound effect on manufacturing and also to a lesser extent on project management and a couple of other disciplines.

So Goldratt was a physicist. He made an observation that was relatively obvious, or at least that’s what he claims to a physicist, about how production environments are planned. I think he had a brother-in-law who had a chicken coop manufacturing business. He recognized that a conspiracy between dependency and variability in production environments lead very easily to environments becoming chaotic.

In order to eliminate this chaos and make production environments more manageable, what one has to do is to understand the interplay between variability and dependency.

To give you an example of what I’m talking about here, in the U.S. if you in the morning or in the late afternoon are merging onto a freeway, your progress will be impeded by a set of traffic lights there to regulate the on flow of vehicles onto the on ramps, because traffic engineers know that if you have more than a certain number of cars on the freeway then you end up with bottlenecks appearing almost at—well, not almost—literally at random.

So the purpose of those lights is to limit the flow of cars to just below the point where bottlenecks start spontaneously appearing. The Theory of Constraints takes that same understanding and applies it to production environments. So it’s an approach to planning or scheduling to use a technical term, the plant. And a way of managing flow to maximize output.

Interestingly, in the TOC world we view bottlenecks as a positive thing. So lean people for example will look at a plant and say, “We have to de-bottleneck the plant.” I think the difference with TOC people is we will look at a plant and say, “Well, unless we expect output to go to infinity, we must accept that there will be a constraint somewhere.” So given that, we want to choose which resource will be the constraint. Then we want to use the existence of the constraint as a source of management intelligence and a way of controlling the performance of the plant.

The first step when it comes to controlling is to ensure that it doesn’t become chaotic which brings us back to the traffic example. Now the book was a book that explains a relatively complex story as a fictional tale. It’s kind of like the business equivalent of Atlas Shrugged. It is probably the bestselling business book of all time and continues to be today.

I was lucky enough to meet Eliyahu on a number of occasions and speak at conferences. I actually sent him a paper maybe ten years ago theorizing about how TOC could be applied to what we’re doing to sales processes. He was impressed with it so I ended up becoming I guess a part of the TOC community which is a whole bunch of engineers. So I’m probably one of the few non-engineers who’s kind of accepted as part of the TOC community.

Roger Dooley: Part of your theory of improving the sales process is an almost manufacturing-like division of labor, right? Where rather than having individual craftspeople building products, it’s much more efficient to have people specialize in various kinds of activities and bring their work together as a team. In essence, you’re saying we should do that with the sales process. Describe how that works.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Yeah, I think most organizations are evolving towards division of labor already in sales. I mean, most organizations we go into there’s a customer service team where that is meant to be processing orders and generating quotes and handling issues but you have competition between sales and the customer service team. Or there’s a marketing team that’s meant to be generating sales opportunities to salespeople but there’s competition. Salespeople are doing it too.

I think in most organizations there’s a general understanding that division of labor is the pathway to increased productivity but I think that sales departments don’t have an understanding of—they probably don’t have a theoretical understanding of what they’re doing and they don’t have a game plan to apply division of labor properly. And they don’t understand that it’s an all or nothing proposition. You either have division of labor or you don’t.

I think that if you want to have division of labor there are some fundamental changes that you need to make to sales. You have to get rid of commissions. You have to get rid of this idea that salespeople own accounts. And you have to centralize planning or scheduling.

The same applies in production or project environments, but I think in sales environments organizations are at this strange kind of transitional point where they recognize that division of labor is the direction of the solution but they’re reluctant to say goodbye to some of the precepts that are almost axiomatic, like salespeople should earn commission and salespeople should own accounts and so on.

Roger Dooley: That sounds like heresy.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Exactly it sounds like heresy. That’s probably why it hasn’t happened. But what I try and do in The Machine is to layout the reasoning so that people understand look this is the direction we’re going in anyway. If you want to do it properly, then here’s how to do it.

Roger Dooley: So what would the functions be in a typical sales organization? I agree that most places probably have outside salespeople, maybe an inside sales or customer service desk to handle the phone calls and maybe order expediting and that sort of thing and separate marketing, but what would a sales team for 2016 look like?

Justin Roff-Marsh: The first thing we would do if we go into an organization is we would look at these sort of nascent customer service and marketing departments and say, “Before we touch sales, the first thing we have to do is fix these.” So customer service has to have the capability and the capacity to handle 100 percent of order processing, quote generation, and issue resolution. 100 percent.

Marketing has to have the capacity to generate 100 percent, or more than 100 percent of the opportunities that salespeople are going to be working on. They are the two preconditions to change sales. So the first thing we have to do is fix that. Until we can stop salespeople from being involved in customer service and until we can remove the requirement for them to generate their own sales opportunities, there’s not much we can do with sales.

But once we’re in a position where salespeople have more people to talk to than they have time, and once all those customer service tasks have been taken away from salespeople and they have no involvement in them, and that includes engineering and project management and all that as well. Then of course, salespeople have just an absolute explosion in their available capacity by virtue of the ten percent problem that you were talking about at the beginning of the interview here.

Of course, the quality of work that salespeople end up performing goes up significantly. Because if you’re a salesperson who joined the profession because you wanted to actually stand in boardrooms and convince people of things, then you find yourself doing that 100 percent of the time. And that’s exactly the point that we encourage organizations to get to.

If you have inside salespeople they should be on the phone with headsets on having 20 to 30 meaningful selling conversations a day. If you have field salespeople, they should be doing nothing other than sitting with customers, negotiating transactions, which means four meetings a day, five days a week. Nothing else.

Roger Dooley: It sounds like that’s in one sense a prescription for a much smaller number of salespeople or at least traditional field salespeople just because unless a company increases its business tenfold, if they make these people who were previously selling ten percent of the time suddenly almost 100 percent efficient, which is a goal, I’m sure it doesn’t quite get to 100 but if that’s the direction, then you would need fewer of them.

Justin Roff-Marsh: You would. So the good salespeople get to earn more and get to be busy and even more valuable to the organization than they were previously. And if you were a salesperson who wasn’t a good salesperson who was trying to live under the radar, staying busy with customer service work, then it’s probably not good for you. You’re probably going to get moved somewhere else.

Now the good news is in practice is that when we work with organizations or even when I watch organizations do this themselves after reading The Machine, we don’t tend to see mass layoffs. We do see salespeople who see the writing on the wall and quit. But what tends to happen is that if we can focus good salespeople on selling, what ends up happening is the organization grows.

If we can build inside sales teams consisting of people who have 20 or 30 proper selling conversations a day, that results in a ten times increase in activity levels, probably going to result in an eight times increase in a request for quotes, which is probably going to result in a two or three times increase in the long run on a per capita basis in sales.

So a lot of organizations go down this path, find that the firm grows reasonably quickly and can absorb those people who get displaced from sales roles. A lot of our clients will turn those people into what we call field specialists who are like general purpose fixers out there in the field performing tasks in support of the inside sales team.

So, yes, absolutely salespeople get displaced. We expect that to happen. We want that to happen. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that people get displaced from the organization. Generally, well I think pretty much always, people who go down this path, the head count remains the same.

Roger Dooley: It seems like at the same time that you might be reducing the number of designated field salespeople, you’re also upgrading some of these other functions because in the past that inside sales or customer service function may have been almost a clerical type position that didn’t require a lot of skill and anything difficult was turned over to the salesperson to handle. Seems like those people could be increasing both in number and quality at the same time.

Justin Roff-Marsh: Absolutely. Typically, the size of the field force might go down to maybe 20