Is there a hidden persuasion industry? Do you think people (or even yourself) can be persuaded or nudged into a direction they otherwise would not have taken, good or bad? In the past, while you created your marketing plans, have you ever wondered how to maximize revenue but at the same time avoid sales that buyers later regret?

Is there a hidden persuasion industry? Do you think people (or even yourself) can be persuaded or nudged into a direction they otherwise would not have taken, good or bad? In the past, while you created your marketing plans, have you ever wondered how to maximize revenue but at the same time avoid sales that buyers later regret?

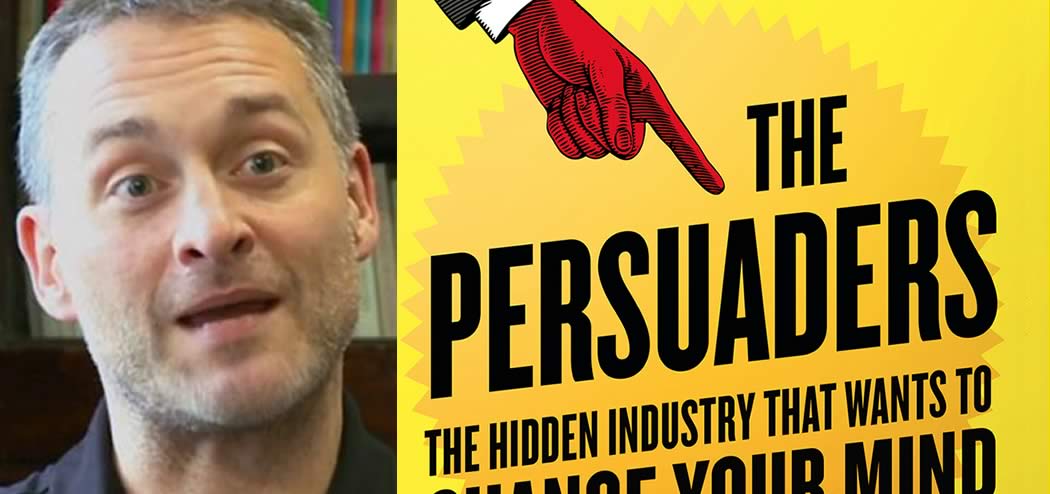

This week, my special guest is a first on The Brainfluence Podcast and you’ll enjoy hearing his different take on persuasion and neuromarketing. James Garvey has a Ph.D. in philosophy, he’s an officer of the Royal Institute of Philosophy and the editor of The Philosophers’ Magazine.

James is the author of several philosophy books, The Great Philosophers, The Story of Philosophy, and The Ethics of Climate Change. His work has been featured in The Guardian, The Times Literary Supplement, The Huffington Post, The New Statesman, and the Times Higher Education.

James’s latest book, The Persuaders: The Hidden Industry that Wants to Change Your Mind, is one that merits a serious look. As most of The Brainfluence Podcast listeners are engaged in persuasion in one way or another, this interview is one you shouldn’t miss. Listen in as James brings his sometimes skeptical but well-informed look at the world of marketing, ethics and persuasion.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why James became a philosopher.

- How The Persuaders is not your typical book about marketing.

- James’s goal when writing The Persuaders.

- Why you need to understand the ethics of neuromarketing before you employ it.

- James’s ethical concerns about the government using nudging.

Key Resources:

- Connect with James: James Garvey | Books | The Philosophers’ Magazine

- Amazon: The Persuaders: The Hidden Industry That Wants to Change Your Mind

by James Garvey

- Kindle Version: The Persuaders: The Hidden Industry That Wants to Change Your Mind

by James Garvey

- Amazon: The Great Philosophers by Jeremy Stangroom & James Garvey

- Amazon: The Story of Philosophy: A History of Western Thought by Jeremy Stangroom and James Garvey

- Amazon: The Twenty Greatest Philosophy Books by James Garvey

- Amazon: The Ethics of Climate Change: Right and Wrong in a Warming World (Think Now) by James Garvey

- Amazon: The Continuum Companion to Philosophy of Mind (Continuum Companions) by James Garvey

- Amazon: The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard

- Amazon: Predictably Irrational, Revised and Expanded Edition: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions by Dan Ariely

- Marco Rubio

- Robert Cialdini

- Zig Ziglar

- The Royal Institute of Philosophy

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is a philosopher and has a PhD from University College London to prove it. If you didn’t think being a philosopher was a real job, he’s an officer of the Royal Philosophy Society and editor of The Philosophers’ Magazine.

He’s the author of multiple books including The Great Philosophers and The Ethics of Climate Change. Before you check your player to see if you’ve accidentally tuned into the wrong podcast, let me explain why I thought you’d enjoy today’s session.

Our guest’s newest book is The Persuaders: The Hidden Industry That Wants to Change Your Mind. Many of our listeners are part of that industry in one sense or another so I thought it’d be interesting to get a different perspective. Welcome to the show, James Garvey.

James Garvey: Thank you very much and thank you for taking the risk.

Roger Dooley: Oh well, perhaps you’re the one taking the risk, but I think we’ll find it fairly risk-free but hopefully an interesting discussion.

So, James, at what point did you decide to become a philosopher? That’s not the most popular career path these days.

James Garvey: No, no, it’s not. I suppose I was at university and I intended to be a lawyer. I found that what interested me was the arguments. So philosophy is the land of argument and I just got drawn into that as a result of reading Plato I think it was.

Roger Dooley: Hmm, very good. I think there’s some pretty good overlap between law and philosophy. So it’s not that big of a jump except perhaps in the outsized paychecks that some lawyers make.

[Laughter]James Garvey: You don’t go into philosophy for the cash.

Roger Dooley: Right. Darn, if only all those philosophy grads knew that to begin with. I don’t know if the quote made it across the pond or not but Marco Rubio, one of the presidential primary candidates here in the states, said specifically the US needs more welders and fewer philosophers. Listening to that quote, it sort of brings to mind an image of thousands of philosophers standing in bread lines because they can’t use a welding torch. Did you hear about that?

James Garvey: It certainly reverberated throughout the philosophical world, even in the United Kingdom, yes.

Roger Dooley: So perhaps, well you can always take up welding if this philosophy thing doesn’t work out.

James Garvey: I’d love to.

Roger Dooley: But I think he probably could have chosen a more representative example. But, in any case, it was amusing.

So I think philosophy is underrated, James, not necessarily as a career but as something that everyone should be exposed to. I’m not sure how it is in the UK but today a student can graduate from just about any US university without having been exposed at all to history’s great thinkers and their thinking. I think only Columbia University and a few others really demand that all of their students read both philosophy and literature. To me, that’s a loss. Is that true across the pond as well?

James Garvey: I think philosophy and the liberal arts generally are under a lot of pressure, especially as budgets tighten. There’s a lot of reason to think that having a philosophical background not only as you say makes you a member of the Western civilization but it also enables you to think critically and carefully and see through fallacies. And that’s a very valuable skill in a democracy, having a public that’s able to see through demagoguery for example.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and unfortunately demagoguery seems to be on the rise.

James Garvey: Yes, it does.

Roger Dooley: And the minds seem evermore closed. I think the one thing that reading philosophy does is it at least opens your mind somewhat to other ways of thinking. Today the trend is to dismiss other ways of thinking sadly.

James Garvey: You sound like Bertrand Russell in a way because he said that the value of philosophy had to do with the fact that it forces you to question the kind of beliefs that are just handed to you by your culture. If you don’t question those beliefs and you don’t make up your own mind, it’s not your life you’re living because those aren’t your beliefs you have.

Roger Dooley: Right. You know, in the US, one of my other interests is higher ed. Not my primary interest but I’ve been affiliated with the field for a long time. There actually seems to be a movement afoot to prevent people, particularly students, from being exposed to ideas they’re not comfortable with.

To me, that’s the worst possible thing that could happen. I mean, that’s to me part of what a college education is about which is to be exposed to some things that perhaps make you uncomfortable. Then ultimately arrive at your own conclusions. But now people will skip classes, not read readings, because there might be something offensive in it.

James Garvey: I mean, we’ve had the Enlightenment, right? So if you disagree with something that someone says, I mean, the obvious thing to do is to have some arguments about it rather than running away from it. If I encounter something that I find offensive, I question it. I point at it. You know, if I hear something racist, I talk to the person who said it. I wouldn’t want to close my ears and head in the other direction. But I’m old fashioned like that.

Roger Dooley: Right. So, James, I think probably the first advertising book I ever read when I was rather young was Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders. Do you think your book The Persuaders is an heir to that legacy in some way?

James Garvey: If only, I love that book. I found it fascinating and I read it again when I was working on this book. In fact, Packard appears quite a few times and so does his nemesis Dichter, the man behind all of those psychological studies of things like cheese and raisins and chickens. He was an amazing man and his descriptions of those things are astonishing. But I absolutely would love to be in that tradition.

Roger Dooley: I should mention to our listeners since we brought up your book that it is really very readable when I saw that it was a book written by a philosopher I was just envisioning like long passages from Thomas Hume and such.

But there are a few quotes in there and I think the last chapter gets a wee bit philosophical but there is a lot of very readable discussion of if you want to call it psychological manipulation or other persuasion techniques. Not necessarily from a how-to standpoint because that’s not your thing but it’s really I thought a fun read and provides a different perspective assuming that your mind isn’t totally closed yet.

James Garvey: Yeah, that’s nice of you to say. I think that one of the aims in writing was to make it readable. I know, like you know, that simple words and stories are far more effective than complicated philosophical treatises when it comes to persuading someone of something.

So part of the aim for me anyway was to find the stories behind the history of persuasion. Examine what it is—what made public relations what it is? Who are the characters? What were they up to? What’s behind political messaging? What stories are there? What can we learn from what happened with Bush and Kerry say. How does branding work? But not just what are the techniques but how do these things come about? How were these theories formulated?

Those stories were far more interesting to me, so that’s the kind of book I’d want to read. So that’s the kind of book I’d want to write I suppose.

Roger Dooley: Right. And of course, neuroscience will tell you that stories are indeed a powerful way to reach people’s brains. Even if you’re trying to persuade, stories are an effective tool.

James Garvey: Well our forbearers didn’t sit around the campfire with PowerPoint presentations. They told stories and there’s a good reason for that I suppose.

Roger Dooley: Little did they know what they were missing. So one thing that might be heartening to you James is that I speak at a lot of conferences and very very frequently one question that comes up is, “Is what you’re talking about ethical?”

There is a lot of concern I think among people who are in the marketing business, advertising business, PR, and so on that they want to create effective messaging for whatever their cause is, whether it’s selling soap or a politician. But a lot of them are indeed concerned about doing it in an ethical manner.

Also I think if you listen to the top persuasion experts, whether it’s Bob Cialdini or maybe other folks, when they write or when they speak, they really do emphasize that this stuff needs to be used in an ethical way. If you’re going to use social proof, you want to be sure that it is accurate. You don’t invent your social proof and so on. And that you have the best interests of your target, your listener, viewer, whatever at heart.

So I think there is perhaps some hope from the industry in that respect and I think that your message would be well received by these folks because it gives them a way of thinking about that concept and resolving whatever inner conflicts they may have.

So early on you relayed a story about how you were listening to a speaker and then presented a devastating argument that clearly showed factually that your viewpoint was correct. But the speaker then proceeded merrily along without changing viewpoint or even sort of acknowledging that you had made an effective point. Then you used that to basically say that this led to sort of an epiphany of yours that people can be extraordinarily irrational.

I’m not a student of philosophy but I would have thought that would have been an ongoing theme because certainly the philosophers through the ages recognized that possibility before behavior scientists started doing their research and Dan Ariely wrote Predictably Irrational.

James Garvey: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Is that not true, or?

James Garvey: The thing is that in the philosophical world we’re surrounded by arguments. That’s all we do. We listen to arguments, we critique arguments, we give counter arguments. Our hero in all of this is Socrates. He’s the man who followed the argument wherever it led. If the premises lined up in a certain way, the conclusion had to be true. That’s what he believed.

And I think a lot of philosophers have the view that if they’re persuaded by an argument, that’s what they will have to believe. When we’re in the seminar room, that’s the kind of view that we push on our students. I think as a—I maybe naively thought that that’s also what we do in the public square sometimes. You know, people come together, they have arguments, and whoever has the best arguments, we go forward together. We believe that person and move forward together.

I know that human beings are irrational and I know that all sorts of things are going on and philosophers have gone on about that. You know, the heart has reasons that reason doesn’t know. Philosophers have known that for a long time. But I did think that arguments were more powerful than in fact I think they are now. That other forces are behind the conclusions that we arrive at.

This instance that you described, when I won the argument but no one noticed, when I talk to friends about this in the pub they had similar experiences. They had the same sort of thing that happened when talking about politics. So that’s what got me interested in trying to work out what it is that’s really behind our conclusions. If it’s not good reasons, what is it?

That’s led me skirting into this world, having to do with the mechanisms of persuasion. But as you say, the thing that—I think you and others know far more about this stuff than I do—but the thing that I can maybe bring to it is trying to work out what the meaning of it is. And as you say, the ethical discussions I think are fascinating and I’d love to deepen those and to expand on those. And to try to understand how ethics are understood maybe in the world of neuromarketing.

You mentioned you wouldn’t want to use social proof that isn’t there. I suppose something like buying Amazon reviews would be a morally wrong this to do. But there are other moral—I guess, does ethics enter into it in other ways to you?

Roger Dooley: I think when this issue comes up, I think that we all have to see the question as sort of a continuum of things that are clearly bad and improper and immoral and perhaps even illegal to things that are arguably quite good.

If you can persuade somebody to save more money for retirement as opposed to ending up at retirement age penniless, that’s probably a universally good thing. And few people would argue with the concept that, wow, if you can use some persuasion psychology to help nudge them in that direction, then that’s great.

But I get back to a quote that I stole from Zig Ziglar who’s perhaps the most famous, best-known salesperson of all time, wrote lots of books on the topic. His topics could be in some ways manipulative. In other words, he wrote one book about all the different ways to close a sale. In other words, you’ve got a customer that you are in the room with or in contact with and here are some ways that you can get them to move off the dime and sign the deal.

In one sense, those techniques are manipulative but his comment was that your most important persuasion tool is your own integrity which is kind of a hard-to-interpret statement. But the way I interpret it is that if you are helping—and he did expand kind of in this direction in other places—that if you are helping the customer get to a better place in some way, then helping them make that decision is fine.

Obviously if you are going to give them a product that they don’t need, that they’re going to be unhappy with and have regret after buying the product, then that’s not a good thing. I think that Ziglar always tried to, even when he was making a sale, ensure that the customer was going to feel better after the sale than before.

He even gave an example of what sounded like a manipulative sale to me, that sold a woman who did not have a lot of money an expensive set of pots and pans which was a sort of big thing in direct sales some decades ago where you had door-to-door salespeople would who sell these expensive cooking sets. At first glance, say that well that woman did not need an expensive cooking set. She was fine with what she had currently.

She could have gone to a store and bought an inexpensive sauce pan if she needed one and so on. But in this case, for that woman, tears came to her eyes when she saw the pans in her cabinet and she knew that now she could show her friends—it made her feel really good about herself in what perhaps might have been a grim existence. In that way, she was in a better place.

Now you could argue back whether that was the best possible use of those funds. But at least for Ziglar, in his case, he did get her to a better place even though it wasn’t necessarily the most logical of purchases. So I guess that’s been my approach.

James Garvey: There’s a thought in the—I think it’s Ernest Dichter—it’s talking about making people happy by creating desire. His view was that if you’re someone who gets close to fulfilling the desire but never quite gets it, that’s the secret to happiness. It’s always sort of striving for something but never quite getting there. He thought that creating desire in other people’s minds for various products that they might buy was the way to bring about I guess happiness in their lives.

I’m sympathetic to that but I think there’s also maybe some evidence, or some reason for thinking that in fact there’s too much of this in our lives. That a lot of desire is created for things that we think are essential and that we think we need, but in fact we don’t. That even happiness might be better served if we’re pointed in other directions, maybe away from thinking of our happiness as consisting in owning stuffing.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well if there was just one pitch that said, “Wow, if you own this item, that you’ll feel a lot better about yourself.” And then that desire could be fulfilled, that would probably be okay. But if you get a thousand messages saying, “Own this thing and you’ll feel better.” Then clearly you can’t go out and buy all those thousand things so you’ll end up having a sort of missing-out feeling that, “Gee, I got these five things and they’re nice. But wow, there’s all those other things that I didn’t get.”

James Garvey: Exactly. To some extent, that’s the world that a lot of us inherited.

Roger Dooley: So, James, you talk a lot about, at least to some degree about neuromarketing and some of the more technical tools used. Not in detail on the technology but on sort of the ethics of using them.

I’ve been following that field and writing about it practically since its inception and I’ve seen two schools of thought that have been critical both from outside the industry. Because within the industry, you have a lot of companies that are promoting their techniques as being effective and helpful to advertisers and so on.

But the two criticisms are almost in direct opposition. Where one school of thought is that this stuff doesn’t really work and that all the purveyors of neuromarketing services are charlatans and they’d be better off just to be ignored. The other school of thought is diametrically opposed saying that these tools are so powerful that they present really a clear and present danger to human free will.

I’m curious where on that spectrum do you fall after having looked at the industry from the outside a little bit?

James Garvey: I mean, I bumped into both of those views. It seemed to me that there was a kind of—I kind of thought that neuromarketing can’t be right because on the one hand as you say because it’s a mistake to think that brain events are conscious events or the interpretation of these signals was far too difficult. And I did bump into that briefly.

That it is, as you say, that there are charlatans categorically sponsoring some study that showed that chocolate was better than kissing or something like that. It did seem to be just public relations or advertising dressed up. But I think the interesting stuff, the action, has got to be at the other end or near the other end. Where there are questions about as our theories approach correctness.

As we get better and better at understanding what’s going on in the brain and how that relates to desire and pleasure and pain and all those things. As we get better and better and better at that, at what point do we begin to wonder whether we’re just treating people as a kind of a means to be manipulated rather than a kind of person who should be thought of as a free agent in the world?

There I think that’s where the interesting questions are. Just short of thinking that neuromarketing can open up the key to, I don’t know, pressing buttons and making people buy things, just short of that because I think that’s probably a bit silly too. But I mean, if you want to go philosophical just for a second, there’s a lot of moral theories out there. One of them is owed to Immanuel Kant who tells us that we should almost treat a person as an end into themselves, never simply a means to our ends.

What he means by that is that people have goals and agendas and responsibilities, a kind of dignity that objects don’t have. We might use an object however we like, but a person deserved respect. So if you begin to see a person as an object, an object that’s sort of emitting signals that you can key into and use in certain ways, then you’re getting into some sort of moral danger from the point of view of Kant. You’re beginning to treat a person without respect or dignity.

I think those questions ought to be asked and addressed and thought about carefully because I think the moral questions are the hardest ones and the ones that ought to be asked.

Roger Dooley: We’ve been talking about using behavior science and neuromarketing techniques for sort of crass commercial purposes but what about government use? One kind of amusing anecdote—perhaps not that amusing for some of the people involved—was the debating societies in London that sprang up in the 18th century where these were basically places where people could argue. They could disagree. They could have rational discussions.

And really apparently somehow the government found this threatening and sent armed thugs into break up these societies. That really doesn’t happen that much in developed Western countries these days. It probably still happens in some places where free thought is potentially dangerous to the status quo. But now what we see are governments setting up these nudge units that are actually exploiting people’s irrationality to accomplish what are presumably desirable objectives but sometimes desirability is in the eyes of the beholder.

I mentioned before, getting people to save more for retirement. That’s probably almost a universal good. Few people could argue with the desirability of that goal but certainly government could nudge you in different ways. Perhaps to agree with more controversial policies of theirs or to promote their particular political beliefs and so on. What do you think about the government using these techniques?

James Garvey: I think that there’s a spectrum, since we’re talking about spectrums today. There’s a spectrum. So it’s true that nudging is becoming increasingly popular. I read a study, something like hundreds of policies all over the world, I mean a huge number of different countries are either informed by or in some sense influenced behavioral economics and nudging.

The United States had a nudger-in-chief in Cass Sunstein was involved in passing regulations and in that regulatory capacity, he applied nudge theory. In the UK, we have the nudge unit which was set up in Downing Street to advise government. It had a lot of effects. As you said, it did some good things. It got people to pay taxes by letting them know that other people were paying taxes. That social proof move increased revenues.

It did another good thing, which it increased organ donation with a number of trials. They used things like social proof and scarcity and reciprocity and cognitive dissonance to try to beef up the messages that people ought to donate organs.

Then it did some questionable things. So it was involved in what’s maybe on the, instead of a soft nudge, maybe on the hard shove end of the spectrum where it tried to help job seekers—I say help with scare quotes around it. It tried to help people who were looking for work. It tried to help them get back into work.

Among the things it did was it gave them a kind of bogus psychological test that was meant to identify their strengths. No matter who takes it, the strengths are all pretty similar. I took the exam. It was still online. It’s gone now. It gave me a whole raft of amazing skills and strengths that I never knew I had primarily because I never did.

That I think was meant to give people a kind of hope and a push and a self-belief to get them back into work. But it’s dubious because it was a lie for one thing. It’s probably not true that giving people a false conception of their strengths is a good way to get them back at work.

So the nudge unit over here got into some trouble and the newspapers kind of turned on it. The way I think of it when it comes to whether a nudge is right or wrong, morally right or wrong, you can think of it in terms of the consequences which I think you do when you said that who would object to getting people to save more. I think that’s right.

But you can also wonder whether or not a nudge affects the means someone might choose to get to their own goals that they’ve chosen. Right? Or whether or not the goals are set up by the nudger. So if you’re being nudged into goals that aren’t really your own, I think that’s morally problematic. But if you can choose your own ends but the nudge concerns the means, you’re given a better means. So I might want to retire comfortably and the means I’m giving is a nudge in that direction, then that’s perhaps less problematic.

But another objection to nudging has to do with whether or not we really want our governments to get good at this kind of thing. Do we really trust them enough to nudge us in good directions? I suppose one final—I’m on a roll—a final objection has to do with freedom.

There’s a philosopher called Isaiah Berlin and he had a concept of freedom that was roughly, “When I act freely,” he said, “I’m conscious of myself as a thinking, willing, active being. I’m responsible for my own choices.” And this is the kicker. He said, “And able to explain them by references to my own ideas and purposes.”

So when I’m nudged, it’s true that I choose. You know, I choose the fresh fruit and not the chocolate cake but I really don’t understand and I really can’t explain why I’ve made that choice because I don’t know whose ideas and purposes are really behind my choice. So there’s a sense in which it compromises freedom and maybe that’s a word for the nudgers out there.

Roger Dooley: Another interesting experiment that you mentioned that probably many of our listeners are familiar with is the famous, or infamous, Facebook experiment.

James Garvey: Yes.

Roger Dooley: In adjusting people’s newsfeeds to change their emotional state or behavior. What do you think about that?

James Garvey: I think that’s fascinating and also, I mean obviously, a concern. There’s a sense in which manipulating people’s emotions by messing with their technology first of all undermines any credibility you might have in the company that’s doing it. So Facebook allows that to happen. Their reputation is damaged in some way.

But the possibilities for future kinds of persuasive techniques that that opens up is I think very interesting. So imagine you’ve got a world in which everyone is connected maybe in new ways. So not just by their phones but something like Google Glass or maybe a generation beyond that. They’re getting a lot of messages that might be sort of tuned directly to them. Maybe not just their newsfeeds, maybe something more extravagant than that.

I think that the future of persuasion, things like moodvertising that I’ve read a little bit about it, messing with empathy, and not only empathizing, like a mobile device empathizing with you. But then also matching your mood and changing it in some way I think it’s fascinating. And obviously worrying if it’s used in unpleasant ways.

Roger Dooley: You mentioned another study with Google with search engine rankings where people were asked to search various topics and were given slanted search results geared toward I think it was—were they political candidates? Then people’s attitudes towards those candidates were measured. The way they saw the search results presented did in fact change their opinion of the candidates.

So I think in some ways these entities like Facebook and Google are potentially more powerful and more insidious—not that they intend to abuse this power. And I think that probably there would be a strong effort to prevent them from abusing it but more so than traditional news outlets because at least if you are listening to a particular news network, you probably have some idea if they’re biased in one direction or another.

If you’re a rational actor, which you may or may not be it seems. But you can probably discount some of the bias so you know that if they’re reporting on a particular candidate that they’re likely to be for or against that candidate and you may discount some of what they’re saying. But when you see something coming up in a search engine or in a social media feed, you don’t really have any sense at all if the entity is biased.

James Garvey: Yes. And in fact, the authors of the study mentioned said that Google might change its algorithms and support one candidate rather than another. And because those algorithms are secret, we wouldn’t know. And we wouldn’t be able to tell that that was going on.

They also say that these people in the study because they came to their own conclusions, having read the different articles that they searched for, even though they didn’t know that those articles were slanted in one direction or another, they thought that it was their own conclusion they were arriving at so they believed it in a way, in a sense, more deeply.

So if your Googling around and you’re not aware that the algorithms have been changed and you come to what you think is your own conclusion, as you say, no one knows that it happened. Then there’s no sense in which your guard is up because you’re listening to what you know to be a biased source. So it’s fascinating in lots of ways I think.

Roger Dooley: Are there any fairly recent egregious examples of manipulation that you can share?

James Garvey: Well my eyes are very much on the nominations in the states. My eyes are also very much on the recently announced referendum in the UK. So the people in the United Kingdom are being offered the choice to stay in or leave the European Union. And obviously there was much discussion about how that referendum was worded. As you might imagine, the wording of the referendum makes a huge difference. They found a neutral way of wording it or anyway of an acceptable way of wording it.

But now the persuasion starts and already it’s degenerated into kind of a personality contest. So one side, those who want the UK to leave are attacking the prime minister, not for any substantive reasons I might add, but because they think he negotiated badly.

On the other side, those who want to go, they’re being attacked because it’s again, not for good reasons, not that it’s in the interest of the country but because Boris Johnson is doing this for his own careerist reasons. That’s what’s going on. So I’m very much interested in watching how this country is persuaded and manipulated by those two forces.

And then I’m also very interested to see what goes on in the United States as the nominations proceed.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well I think the exiting the EU issue is particularly interesting because the government may have an opinion on that and hence could use its resources in a nudging way to try and guide things. Now obviously, I would think that their ability to do that would be somewhat circumscribed by the opposition but still that’s an example of I think a place where a government nudge might not really be appropriate.

James Garvey: No. What they will be doing though and what they’ve started to do, is play on fear and emotion. Part of what interests me in how persuasion has changed over the years is that we seem to no longer argue with one another. We don’t give each other reasons as much as we used to do. I think that’s changing a lot in the world.

But one of the things it’s changing is political discourse. In this country, I’ve already heard the government is in favor of leaving the EU, or at least the prime minister is. He’s begun to say that we will get a lot of immigrants into the country, we’ll get a lot of people here that they’re trying to keep out. We’ll be more susceptible to terrorism. And these are playing on fears I think. I don’t it’s anything more than that.

Roger Dooley: Not that dissimilar to what’s happening in the presidential contest in the states.

Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with James Garvey, philosopher and the author of The Persuaders: The Hidden Industry That Wants to Change Your Mind. Even if you’re a part of that hidden industry, or aspire to be, I think you’ll find James’ book to be well researched and thought provoking. It also has plenty of references to research about persuasion science if you want to dig deeper. If you do get any ideas from James’ extensive research, please use them for good, not evil.

James, how can people find you and your content online?

James Garvey: If you just Google the Royal Institute of Philosophy you’ll find me there.

Roger Dooley: Great. Okay, we will have links to that place, James’ book, and anything else we discussed on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/Podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. James, thanks for being on the show.

James Garvey: Well thank you very much for inviting me.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.