As you all probably already know, neuromarketing is the application of newly discovered truths of neuroscience to the art of marketing, which can be used to effectively persuade your target audience; that is if you understand the language of the “lizard,” or the non-conscious part of our brain. Some call it the reptilian brain.

As you all probably already know, neuromarketing is the application of newly discovered truths of neuroscience to the art of marketing, which can be used to effectively persuade your target audience; that is if you understand the language of the “lizard,” or the non-conscious part of our brain. Some call it the reptilian brain.

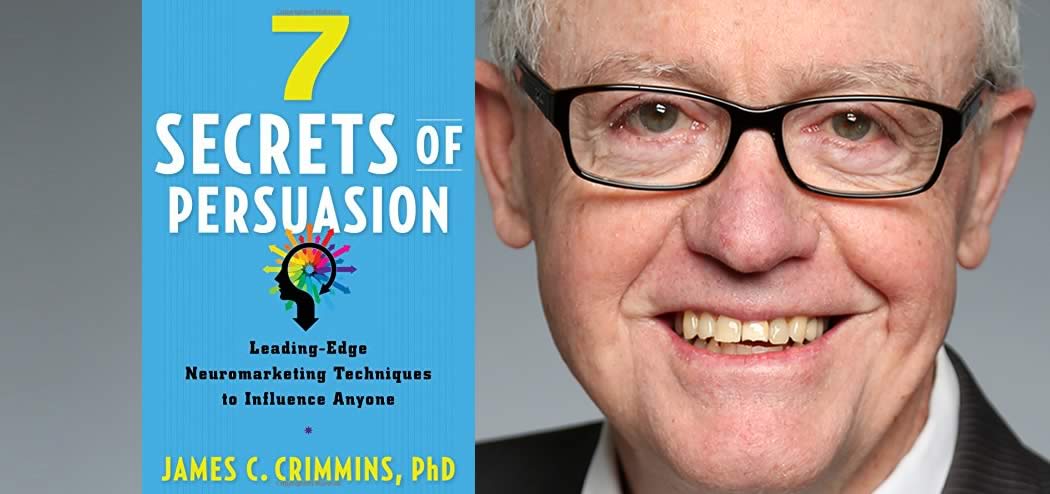

Our guest today is Jim Crimmins, author of 7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence. Jim is a professional persuader and has an impressive background of academic and real-world credentials.

We discuss the principles of persuasion and how small businesses or entrepreneurs can leverage these principles to target behavior changes on par with professional marketing agencies. Persuasion is done best when people persuade themselves. Jim illustrates simple ways to target behavior rather than attitudes in order to establish long-lasting shifts in brand awareness, and explains how emotion can trump logic.

Jim Crimmins has been a professional persuader for 27 years. He has worked as the chief strategic officer of DDB Chicago and as a worldwide brand planning director for clients such as Budweiser, McDonald’s, State Farm, and Betty Crocker.

Jim has a PhD in sociology and a master’s degree in statistics and has taught integrated marketing communication at Northwestern University’s Medill School. He combines his scientific, professional, and academic background to explain how the revolution in mind science changes the conventional wisdom of influence and can make anyone a more successful persuader.

In 2014, he launched PersuadeTheLizard, a site that is no longer active but that ranked advertisements, PSAs and political ads on their ability to persuade. The site has been featured on AgencySpy, AdCouncil, and on radio stations across the country.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Five aspects of the power of language in the non-conscious part of our brain.

- Why changing behavior is easier than changing attitudes.

- How to determine the leverage points when attempting to change attitudes and impact preferences.

- An example of why targeting irrational choices will have no impact on behavior.

- Why the Energizer Bunny has had a lasting impact on our collective consciousness.

Key Resources for Jim Crimmins:

- Connect with Jim: Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: 7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence

- Kindle: 7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence

- Audible: 7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week is a persuasion expert who brings an impressive combination of academic and real-world credentials to the show. He was a professional persuader for 27 at DDB Chicago including the position of chief strategic officer. He was a worldwide brand planning director with clients like Budweiser, McDonald’s, State Farm, and Betty Crocker. He has PhD in sociology and a master’s degree in statistics from the University of Chicago, and he’s taught integrated marketing communications at Northwestern. His new book is 7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence Anyone. Welcome to the show Jim Crimmins.

Jim: Hello, Roger. Happy to be here.

Roger: Great. I enjoyed your book, Jim. It’s very practical in its organization and it focuses on the science underlying its recommendations which our listeners always appreciate. To begin, why don’t explain what you mean by neuromarketing in the book’s title?

Jim: Neuroscience is the study of the brain and in the study of the brain great leaps have been made in the last few decades and neuromarketing is simply the application of those newly discovered truths of neuroscience to the art of marketing.

Roger: Right now, I guess, I would distinguish different kinds … I guess I’ve been probably, at least, partly responsible for corrupting the term neuromarketing because originally new people used it to refer to very specific neuroscience-based techniques like FMRI or EEG to evaluate advertising. I’ve always been in favor of a somewhat broader interpretation of the word that really bring in a variety of neuroscience and behavior science to help our marketing and advertising efforts. I take it you’re sort of in a ladder camp too, right?

Jim: I am in very similar and very similar place as you, Roger.

Roger: Good. Start off by in your first chapter, you title it getting to know the lizard. I’m sure that at least some of our listeners are familiar with the trying brain theory, but why don’t you explain who the lizard is?

Jim: The lizard is a term I use and that actually was used first by [inaudible] to refer to that part of our brain that we are not conscious of, the non-conscious brain which is over 90% of our brain’s power. The lizard has it’s on way of speaking, has it’s own language and in order to persuade, we need to understand and be able to use the lizard’s language.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What is the lizard’s language?

Jim: The lizard’s language has, as I’ve laid it out in the book, 5 separate aspects. First of which is mental ability. Whatever pops in the mind first. We are all biased toward whatever comes to mind most quickly. We have the most confidence in it and we are most likely to choose it. Secondly, association. Simply the pairing of one object with another. Whenever any idea enters our brain, many other ideas are dragged along with it, that have been associated with it. Association is very powerful force but it is also a force that can be influenced. Thirdly, action. Lizard the non-conscious mind pays close attention to what we do and ignores why we do it. Psychologists, as you know, refer to this as fundamental attribution error. People pay close attention to action and ignore motivation. Fourthly, emotion. The non-conscious mind uses the language of emotion to communicate with the rest of the mind suggesting we approach and avoid certain things who are … emotional reaction to it and the non-conscious mind responds to emotion. It doesn’t speak the language of logic and information, it’s the logic of the conscious mind, the reflective mind. The non-conscious, lizard inside mind responds to emotion.

Lastly, the preferences of others. We all pay a great deal of attention to what other people are doing. None of us has the skill, or the ability to evaluate all objects in the around the choice we have to make fairly. Even experts struggle to determine which investment might be best or which automobile might be best, or even which beer might be best. We pay close attention to what other people are doing and take our cues from that. The preferences of others guide our action and inform us of the quality of the options under consideration.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative), so that’s really what drives a lot of the social proof, things that people use in terms of how many customers we have, how many buyers, how many subscribers, and so on. Jim, you came from a big agency environment, I’ve always kind of assumed that the big agencies were keyed into emotion-driven appeals, or non-conscious appeals long before anybody was talking about neuromarketing or doing brain scans on people. Was that now true? Do you think that despite the fact that I guess some campaigns were definitely emotion driven that big agencies and big consumer brands missed the boat fairly often?

Jim: In some respects big agencies led by creative geniuses like Bill Bernbach had an intuitive understanding of how persuasion really worked. However, there are many agencies and many companies that test advertising that have a very different understanding of the way advertising works. They feel it works through information guiding attitude, attitude guiding behavior when in fact the process is often the reverse. The emotional value of an ad was something pursued very heavily in some agencies on some accounts, and not nearly so much in other agencies on other accounts, that emphasized a more traditional flow of advertising or influence from learning, to feeling, to doing as opposed to doing, to feeling, to learning.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I want to come back to that in a second, but I think one kind of amusing example of a brand that was striving for an emotional impact with our ads was “Schlitz Beer” which probably dates beer that we are familiar with Schlitz Beer. They ran an ad that really ended up with an unexpected emotional impact right? Or a serious campaign.

Jim: They certainly did. They ran a campaign that became famously known as “Drink Schlitz, or I’ll kill you”. That isn’t of course literally what they said, but that was the impression consumers got out of it. They would feature rugged, very macho characters. It could be a boxer, or it could be some other character that is potentially threatening and the announcer off-camera would ask this person of they could have their Schlitz, and the threatening person would respond very menacingly. Under no circumstances allow them to have their Schlitz. The desire of course was to communicate how fiercely loyal these people are to Schlitz, but the net effect was they did generate emotion but they had generated the emotion of fright. The impression was that people who drink Schlitz are frightening, and not necessarily the sort of people I want to be with, or be around. It was many marketing mistakes that lead to the downfall of Schlitz.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). You know, sort of the Marlboro man on steroids, or Marlboro man’s evil twin perhaps. I suppose that’s one brand that could have benefited from some actual hardcore neuromarketing. Put folks in a FRMI machine and see their medullas light up. They might say “Okay, maybe we’re not doing the right thing in these ads here”.

Jim: Maybe we’ve taken it just a little too far, yes.

Roger: Yup.

Jim: The Marlboro Man is a very interesting character in his own right, in that many people don’t realize that Marlboro was, for many years a women’s cigarette. It was introduced as a cigarette for women and at one point had red at the end of it to mask lipstick marks, it also for a while had ivory tipped cigarettes (not genuine ivory of course), and used to use lines like “Mile as May”, but in the fifties the brand changed its personality completely and this is a great example of the use of action to speak to the non-conscious mind. When the brand acted macho with initially people with tattoos on their hands, and eventually focusing in on cowboys, and the music to Magnificent Seven, the brand acted very masculine and became perceived as very masculine. The motive was profit, people ignored the motive. They went by how the brand acted and they inferred that the brand was very masculine because it acted so masculine.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). That’s interesting. I wonder why they did that instead of simply launching a new brand. It would seem to be a tougher almost to take a women’s brand and turn it into a men’s brand. Unless there was enough name recognition in the marketplace and they had distribution, and so on. That there were benefits to just refocusing the brand.

Jim: They realized they had only less than half of one share point. Beginning with this brand they didn’t have a tremendous ocean liner to turn around. They had a very small share brand and it was something they could work with.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative), interesting. You talk about aiming for the act, not the attitude and that you’re not … the act is affecting the attitude as opposed to the marketer trying to change consumers attitudes. How does that work? It seems like changing that act is something that would be quite difficult to do.

Jim: One of the surprising things is that it is often easier to change people’s behavior than it is to change people’s feeling. If we think about cheese, for example, a rather mundane example, we did a lot of analysis of why some people eat a lot of cheese, and some people don’t eat much cheese. What we found is that it was not a difference in perception of the taste of cheese, it wasn’t a difference in perception of the price of cheese, it wasn’t a difference in the perception of the nutritional value positive or negative cheese. What it was simply was that some people had in their repertoire all sorts of easy ways to use cheese, and other people had in their repertoire very few ways to use cheese. We found that if we gave people relatively simple easy ways to use cheese, they would use it. What was holding people back was not their attitude towards cheese, what was holding people was the mental availability of many easy ways to use cheese. Once we provided those, use of cheese blossomed. It is often easier, as I say, to change the behavior than the attitude. Everything we do is based on our attitude and circumstance.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Jim: Attitude is resistant to change, circumstance is often much more malleable.

Roger: Interesting. Of course, the probably most obvious approach to advertising to increase cheese consumption to focus on how tasty it is, or how nutritious it is or something like that, but you’re saying the deep dive research showed those weren’t the real issues in question, it was just knowing how to use it properly. Once you could provide that then people could act on it and they felt fine about cheese.

Jim: Yes. The recipes were amazingly simple. They were put a little cheddar cheese on peas and transform them into [inaudible], melt a little cheddar cheese on broccoli and watch the broccoli disappear. Very simple recipe ideas but it worked to move the cheese in a way it wouldn’t if we tried to change attitude because attitude wasn’t the problem. People who ate cheese frequently, and people who ate cheese infrequently agreed that cheese tastes great. That was not our problem, that’s one of the important things in marketing as you know is to make sure you have the right problem figured out because you could end up spending a lot of money and effort trying to fix the wrong problem.

Roger: Right. What if the attitude wasn’t all that good to begin with? Is there a way of dealing with that kind of problem to, other than just hammering away at trying to change that attitude?

Jim: There often a way to deal with that attitude. One of the important things is to figure out where the leverage points are. Let’s take for example, hotels. Looking at hotels, and the attitudes people have towards hotels is all sorts of attitudes we can look at, and figure out where we might be able to make a change and affect people’s hotel preference. We might think about the softness of the beds, we might think about the responsiveness of the service, the cleanliness of the hotel, we might think about the other …, whether the bar is pleasant, or the food in the restaurant is good. Assuming these are all hotels that are roughly comparable in price and accessibility to where we’re going. We found that the attitude that really had the leverage was a perception of the sort of people who stayed there. We found that if we could communicate that sophisticated travelers stayed at this hotel we could make a big difference.

Communication about sophisticated travelers was interesting in that it has broad implications. It communicates that the beds are soft, it communicates the service is good, it communicates the food is great, it communicates the bar is fun. It has broad implications, so by changing the perception of the people that stay at the hotel we could have an impact on many other qualities of the hotel. Whereas if we had simply focused in on something very specific and informational, like the softness of the beds, it would have said nothing about how good the service is, or how good the food is and so forth.

The changing of the perception of the sort of people who do, the user image of the product has wider implications and changing perceptions of some much more specific rational objective attribute.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I would guess too it depends on the segments that you’re dealing with because I think that one of the brands, I’m trying to think if it was Westin or somebody else actually did focus on sleep. Their research uncovered that there was a pretty large segment of travelers that had difficulty sleeping in hotels so they both changed their product in a way to give people a variety of pillow choices and other sort of sleep amenities dealing with issues like noise, and basically anything that could prevent a good night’s sleep they attempted to deal with first, at the product level, and then also then communicate that this is what differentiated them from their competition. I guess it just depends on the segment that you’re after, particularly in something diverse like hotels, because I would guess that there are quite a few different segments of travelers when it comes to whether somebody’s going to stay in a Motel 6 or a Four Seasons.

Jim: Yes, absolutely. There’s radically different segments, as you say. There’s the people who are obviously have a lot of money, or travelling on an expense account and they’re looking at a certain range of hotels than other people who are not as fortunate financially and travelling on their own dime, they’re looking at completely different set of hotel.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). One of the things in talking about the lizard brain, that you point out that when New York City introduced calorie counts on restaurant menus. This was expected to have at least some impact on consumer behavior once people knew what they were actually consuming, and it actually didn’t. Why is that, you think?

Jim: I think the … It was a very interesting piece of information we were able to collect. I was participating on a national institute of health committee at the time about how to communicate health in products there was a lot of discussion of the use of information. Information about nutritional calories, and other nutritional qualities in food and it was enlightening to find out that when New York did this massive experiment where any restaurant that had I think it was more than 10 or 20 outlets had to communicate calories as prominently as price. The net effect however, as you say was zero. People ordered just as many calories after this as they did before, and it was because the choice in food at a restaurant, at a fast food restaurant in particular is not a rational choice. We pick what feels good, what we’re hungry for, what we’re interested in and we then rationalize, we gather the … the information together that will support our choice. People simply picked what they wanted to pick and did not … If a decision is not made rationally, it’s very hard for rational to influence it. The decision of what to order when you’re standing in line at McDonald’s is often not made rationally, so it is difficult for rational information to influence that choice.

Roger: Yeah, there was even a study that showed that adding a salad to the menu increased french fry consumption. Somehow that salad said “Oh, this restaurant has healthy choices so it’s okay for me to have some fries”. I’m pretty sure that fits your definition of an irrational decision.

Jim: I think it sounds like it, yes.

Roger: Yup. Jim, tell us the story of the Energizer Bunny.

Jim: Okay. We spend a lot of time working for Energizer. This was in the days before the birth of the Energizer Bunny. They, of course, are locked in a fierce combat with Duracell, and Duracell has very successfully locked up the notion of long lasting. We were thinking “Okay, we need to find something else.” We and the client all decided that we need to find some other aspect of batteries that we can associate with Energizer to move ourselves ahead in the marketplace. We looked for a long time, we failed to find anything that anybody cared about that was in fact something that we could talk about in advertising. If we could have said “Sound quality is better”, that would have been great, but it wasn’t. It was simply wasn’t true so we couldn’t say that long-lasting was the attribute we needed to competed on.

We introduced a character in our ads, a bunny, that hit a base drum, a cymbal, and marched around while other battery operated devices failed, and this bunny was the Energizer Bunny. After the first ad or two, that featured the Energizer Bunny we were tasked to come up with more ideas, and we came up with a variety of ideas for what to do in the future for Energizer. For the most part did not feature the Energizer Bunny. And other agency at the same time, it was eager to pick up the Energizer business figured out that they could use the Energizer Bunny in a variety of ways. They devised a whole raft of pseudo commercials that were interrupted by the Energizer Buddy. They happened to come through, it could have been a movie, it could’ve been another commercial, it could’ve been anything but all suddenly and unexpectedly the Energizer Bunny would appear because the Energizer Bunny just keeps going, and going.

The client decided that even though we had come up with the Energizer Bunny, the Energizer Bunny of course really belonged to them, not to us and they wanted to use it this other way with the commercial suggested by the other agency and Energizer has gone on to do wonders with the Energizer Bunny and has come to be identified with the battery that just keeps going and going, which is exactly we had originally set out to do.

Roger: Right. That’s about the one performance characteristic a battery has. As long as it fits in your device and it doesn’t end up exploding in your device, or something then what’s left, other than long life? You’re aggravated if it burns out too soon, or dies too soon, and you feel good if it lasts a long time. What do you think it was about the Energizer Bunny that made it such a powerful meme that embeds itself into people’s minds?

Jim: I think it was a variety of things. One of which was, first of all, it’s inherently cute. It’s just fun to see on the screen. Secondly, the bunny I think was brilliant. We placed by shy a day in another advertising agency in commercials where it was a total surprise. You would be watching a commercial you would assume possibly was a fragrance commercial or some other sort of a commercial and you were jolted by the fact that suddenly here comes this Energizer Bunny. I think that element of surprise was enormously useful. Another was they didn’t need to beat the audience over the head with the message. The message was there in the commercial, the audience could figure out the message for themselves. Persuasion is actually something that everyone really does for themselves. The role of marketing and advertising, and persuasion in general is to help people persuade themselves, and I think the Energizer Bunny helped a lot of people persuade themselves.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). One of the nice things to is that it doesn’t involve direct performance, claims. In other words, it would have been very hard to say that “Our battery lasts 30% longer” because that wouldn’t be true, but in this case it established that long lasting brand characteristic without any specific kind of performance data simply because that imagery was so affective.

Jim: Absolutely right. The performance data … In order to be successful in performance data when batteries attempt to do that they always compare themselves to their own earlier stages because they’ve made improvements and they can accurately establish that they perform now a little better than they used to, but the competitor is always neck and neck, so they typically perform exactly like their competitor does.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Jim, a lot of your stories are from big brands. How can smaller companies, and entrepreneurial firms use some of your concepts?

Jim: I think the principles are relatively universal. In fact, the concept of persuasion can be used even in situations that are not commercial law. It could be non-commercial or could be simply persuading someone else in your family. For example, take somebody who’s trying to lose weight. The principle of mental availability applies very strongly. Brian [inaudible] has found that women who have soft drinks visible anywhere in their kitchen weigh roughly 25 pounds more than the neighbor who doesn’t, and women who have fruit visible anywhere in the kitchen weight approximately 13 pounds less than a neighbor who doesn’t. There’s a lot of reasons that causation goes back and forth, but nonetheless, the simple act of changing the circumstance, making the soft drinks less available mentally and physically, and the fruit more available mentally and physically have a dramatic effect on behavior. The [inaudible] the act, not the attitude in changing mental availability are things that can be used even in something as simple as trying to lose weight or help someone else lose weight.

Roger: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Great. That’s probably a good place to wrap up, Jim.

Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Jim Crimmins, author of the new book “7 Secrets of Persuasion: Leading-Edge Neuromarketing Techniques to Influence Anyone”. Jim, how can people find you and your content online?

Jim: The easiest place to go is to my website which goes by the unusual name of Persuadethelizard (No spaces) dot.com. Persuadethelizard.com.

Roger: Great. We’ll link there and to your book, Jim and any other resources we talked about on the show notes pages at RogerDooley.com/Podcast and we’ll have a handy PDF text version of our conversation there, too.

Jim, thanks for being on the show.

Jim: My pleasure, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.