You’re probably familiar with the thrill of stepping outside your comfort zone and meeting success; perhaps in business, a tricky conversation with a loved one, or speaking in front of a crowd. But you’re probably even more familiar with staying firmly planted in that comfort zone, avoiding the discomfort and risk that come along with stretching your capabilities.

You’re probably familiar with the thrill of stepping outside your comfort zone and meeting success; perhaps in business, a tricky conversation with a loved one, or speaking in front of a crowd. But you’re probably even more familiar with staying firmly planted in that comfort zone, avoiding the discomfort and risk that come along with stretching your capabilities.

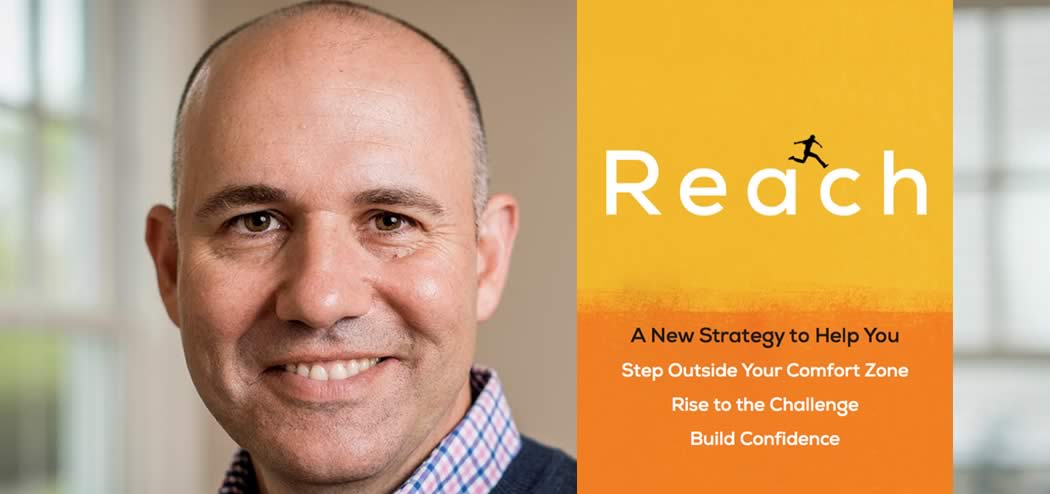

Today we’re sitting down with Andy Molinsky to talk about his new book Reach: A New Strategy to Help You Step Outside Your Comfort Zone. Andy has conducted research on entrepreneurs, doctors, salespeople, and countless others to examine how we both construct and break out of our comfort zones.

Andy begins by talking about why so many people find traditional networking to be uncomfortable or downright off-putting. He also discusses the five categories of comfort zones he’s identified through his research, including procrastination. We also talk about beating impostor syndrome and knowing how to follow your own moral compass.

Andy Molinsky is a Professor of Organizational Behavior at Brandeis University’s International Business School, specializing in behavior change and cross-cultural interaction in business settings. He has degrees from Brown, Columbia, and Harvard, and writes for the Harvard Business Review regularly.

Andy has surveyed people from all walks of life about comfort zones and how to break free of them – so listen in and draw on their techniques to reach your goals this upcoming year.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why many of us find networking to be so painfully awkward, and how to reframe the experience so it’s more positive.

- Suggestions for beating impostor syndrome.

- Why it’s important to discern if you’re avoiding something because it makes you uncomfortable, or if it’s because you have no interest in it.

- How to do “psychological accounting” of the tasks you may be avoiding and determine why you’re doing so.

- Andy’s advice for pushing your limits in the new year.

Key Resources for Andy Molinsky:

- Connect with Andy: Website | Twitter

- Amazon: Reach: A New Strategy to Help You Step Outside Your Comfort Zone

- Kindle: Reach: A New Strategy to Help You Step Outside Your Comfort Zone

- Amazon: Global Dexterity

- Kindle: Global Dexterity

- Natalie Portman‘s Harvard Commencement Speech

- Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is an expert in behavior in the business world. He’s a professor of organizational behavior at Brandeis University’s international business school. He specializes in behavior change and cross-cultural interaction and business settings. He has degrees from Brown, Columbia and Harvard, and writes for the Harvard Business Review on a regular basis.

His first book was Global Dexterity which focused on a key new skill for the 21st century, the ability for an individual to function effectively in different cultures while staying authentic and grounded. His new book is Reach: A New Strategy to Help You Step Outside Your Comfort Zone, Rise to the Challenge and Build Confidence. Welcome to this show, Andy Molinsky.

Andy: Thank you so much, Roger. I’m really happy to be here.

Roger: Great. I think Reach is really a timely book. Andy, I think most of us are limited by our comfort zones. We avoid things that make us uncomfortable even when those things would allow us to grow personally or help our careers or our businesses. One of the topics you mentioned, it’s both on the cover and of course in the book itself is networking.

We all know networking is important, but many of us fail at it. I go to a lot of conferences and there’s always the obligatory networking social hour. You walk into the room and a third of the people are around the periphery staring at their phones in solitary mode. Probably, the majority of the little clusters of people talking are people who are from the same company or who already know each other and there’s probably very little new contact making going on.

I’m sure nobody sets out with that purpose in mind either. Nobody says, “I got to go down to that mixer because I really want to check my email while I’m holding a glass of wine.” That ends up happening in so many cases. Why is that?

Andy: By that way, I should also add, you’ve got people pretending to go to the bathroom three or four times or people checking out things on the wall. It’s amazing, the different ways that we avoid having conversation networking events. I’ve talked with a lot of different people about networking and I have to admit that as it’s true with many other things in the book, I too have experienced the challenges in these situations.

Networking as we know, it can be awkward for a lot of reasons. A lot of us feel uncomfortable approaching people, making small talk for various reasons. Some of us are shy, some of us are introverted, some of us feel small talk is pointless, let’s say. We might not even know what to say. Then when you get into the networking event, many people feel very uncomfortable pitching or promoting themselves. I know a lot of consultants whose job it is in these situations to pitch and promote themselves who feel deeply uncomfortable about doing it.

Roger: You can’t really do it quite that blatantly. You don’t want to be the insurance person at the Christmas party who’s handing out a business card. Hopefully, what you are doing is making human contact with people, getting to know them, finding out what you have in common and then at some point you can then discuss business with them, but even just that human contact that’s the barrier there. I mean, I think once that’s made then discussing what you do or what they do is a lot easier.

Andy: I think that’s true. I think even though logically, people understand what you said. I think psychologically, often times people still feel deeply uncomfortable in these networking situations. I know that there’s been some psychological research about how people when they’re networking in this way feel dirty, like they psychologically feel dirty. On different tests where they have to fill in the blank questions, they often fill them in with words that have to do with cleanliness and dirty.

I think that psychologically deep down even in our unconscious, it feels very uncomfortable. For a lot of people, it actually just helps to reframe the networking event just like you did as a way to make connections, as a way to potentially have authentic discussions. Sometimes it’s helpful for people to set goals.

In other words, my goal is to have a genuine conversation with one or two people and if I really make a connection then I can maybe set up a future conversation in a context that’s more comfortable for me one on one over coffee and so on.

I think networking events are rife for feelings of uncomfortableness, people feel inauthentic, people feel incompetent, people sometimes feel embarrassed. They worry that they’ll be liked or seen as too slimy and so on. It actually can be a very uncomfortable situation for a lot of us.

Roger: I think the typical networking event is a microcosm of a lot of this stuff you talked about in your book. It’s not just one thing, it’s many of those things. What are some of the other types of activities that you found make people really uncomfortable?

Andy: Public speaking is a big one. Speaking up at a meeting, being assertive, speaking your voice, I found that that’s something that’s very difficult for a lot of people to stand up and be assertive whether it’s in a meeting or to their boss or colleagues. Sales, I think a lot of people who aren’t sales people struggle with sales, pitching and promoting their products.

A lot of entrepreneurs who are product people have to really grow in to a lot of different roles, sales and management. They might not be comfortable with entrepreneurs pitching their ideas to venture capitalists especially young entrepreneurs like in a shark tank situation. Delivering bad news, it goes on, and on, and on.

Roger: You’ve classified the barriers that make it difficult to do those things and these cut across those activities. I probably put in things like performance reviews in that really uncomfortable thing. I know that as a manager, that was something that the only thing worse than going through your own performance review is having to deliver someone else’s performance review particularly if it’s not necessarily the best one. That makes it tough, but what are the categories of barriers that make it difficult for people to do these things?

Andy: I found that there are five different barriers across different professions and it’s not the case that in every situation we’re going to experience all these barriers but I found time and time again, these are the barriers people face. One is authenticity. We hinted at it earlier, the idea that this doesn’t feel like me. This really doesn’t feel like me and I don’t like to behave in a situation that feels like I’m a fish out of water that’s not me.

For instance, I hinted at before pretending to put on your grown up voice when pitching to venture capitalist. A lot of young entrepreneurs felt very inauthentic stepping into that business person role when they didn’t feel that way. Likability is another one. That’s a second one to authenticity, likability. Worrying someone might hate you if you act really assertively. Certainly delivering bad news, as you just said. Likability, I think people, again, logically understand it’s their job to deliver bad news but psychologically deep down, worry that the other person will hate them, especially if you’re a people pleaser, let’s say, as many of us are.

Competence is another one. We worry that we’ll look like a fool giving a public speech. We worry that we’ll look like a fool really doing anything outside our comfort zone. It’s like writing with your left hand, being a fish out of water and you can worry inside that you’ll feel incompetent. Also worry that that’s visible to other people.

Resentment is a fourth one. It’s interesting. Again, people logically understand when in Rome act like the Romans. I’m in a performance review situation. I got to do that performance review, but psychologically they sometimes resent the fact that they have to do it. Maybe not in terms of a performance review, but I found that with small talk for instance.

A lot of people feel resentful that small talk and some of the soft skills are so important when their qualifications are really what should matter to get that promotion or get that job, right?

Roger: Right. My product is so great, why should have I to sell it?

Andy: Exactly. I’ve talked with a lot of people who feel that way especially about small talk. For years, I actually have studied not only people stepping outside their comfort zones and everyday life, but my previous book which is called Global Dexterity was about people stepping outside their cultural comfort zones. People from other cultures especially coming to the United States are often quite resentful about how important chitchat and small talk is.

I know people who would interview for jobs who had tremendous qualifications, but they just couldn’t talk about the weather or they’re commuting to the office and that wasn’t getting them the job. They were very deeply resentful about it. I’d say that’s a fourth one.

Roger: I find that quite surprising, actually, Andy because it seems like Americans have had their reputation for being all business and get straight to the point where in other cultures there’s a much more a elaborate socialization process, but are you saying in some cases, that’s not the case and that other cultures are even more direct than we are?

Andy: Definitely. I think there’s a range. I mean, I think that when you’re in Germany, for instance, small talk is just not part of their repertoire in a lot of professional situations, whereas if you go to Latin America, you might engage in a ton of small talk before getting down to business. I think the US in some ways is in the middle let’s say on that continuum, but I think that there is something about small talk in creating that sense of rapport, that a lot of people from outside the United States find very superficial.

I think it is hard for people and I think sometimes people do feel resentful about how important it ultimately ends up being for various reasons to create that quick sense of trust.

Roger: You’re probably seeing the research on that, but there’s some fascinating work done using the ultimatum game that usually it’s where one person divides, say, a small amount of money, say, $10 between himself or herself, and another person, and a second person can accept or reject it. Those deals often end in failure because the first person is seen as too greedy and the second person rejects the offer even though it’s causing them $2 or $3. They still reject it. Merely socializing for 10 minutes before playing the game, reduce the failure rate from 33% to 5%.

That’s something that I actually incorporate in a lot of my sessions is emphasizing that it’s important not to get down to business right away and what’s probably happening there is you’re finding some areas of common interest where you’re generating what Cialdini would call liking effect or even a unity effect, but that little bit of getting to know the person really does positively affect outcomes. I totally agree with you, that’s really important.

Andy: I think that’s really interesting and that study is interesting. I think it’s important as well, but I do think that’s it’s also critical to understand that for some people, it’s actually really hard to do that. For those of us who are uncomfortable making small talk, we don’t know what to say. We don’t know how to engage someone. We don’t know how to start a conversation and we don’t know how to continue it after the first few questions.

I have an Indian MBA student this semester. I teach a course. I teach MBA’s. I teach a course where I force them to step outside their comfort zones. We learn about the process while doing it. She was telling me the other day how her situation was trying to make small talk because for her, coming from India, it’s very uncomfortable to make small talk with strangers in the way we’re talking about.

She was talking about getting her hair cut and how in the United States the person cutting your hair will chitchat with you and so on. She felt like she was trapped because she did not know what to say. Imagine how uncomfortable it is to sit there and to feel like so deeply anxious, and embarrassed, and uncomfortable, and not knowing what to say. She’s a very nice, lovely woman. Then of course on top of it, someone has got a scissors to your head.

Roger: You can’t move so you’re literally trapped.

Andy: Exactly.

Roger: Interesting. Competence is one of the things you mentioned. I assume that’s where the impostor syndrome comes in that seems to affect so many of us?

Andy: Absolutely. I found that time and time again. You find it with people that you wouldn’t even suspect to have the impostor syndrome. In the book, I talk about how Natalie Portman of Star Wars fame, and Black Swan, and various other movies. She was an undergraduate of Harvard and she revealed after the fact many years later how incredibly uncomfortable she felt at Harvard feeling like such an impostor like, “Who am I to be here? Everyone must look at me and think of me as a dumb actress. Why am I in this role?”

She actually came back and delivered a really stirring commencement speech many years later revealing her feelings. It’s funny how many people I talk with who the outside seem so confident and on the inside really feel like an impostor. I site in a book, a recent survey talking about how the number one fear among executives, CEOs is the impostor syndrome.

Roger: Probably the more responsibility you have or have been given the more likely it is to kick in because the importance of the decisions you’re making. I think when you think about being, say, an undergrad student at Harvard, I would think that probably you’ve got two classes of people. Those people who feel like, “Wow. How did I get in here with all these other people? I really don’t belong here.” Then perhaps some narcissist who think, “Of course I’m here because I’m the best.”

Andy: You’re probably right. You probably want to end up somewhere in between, right?

Roger: Ideally. Is there a cure for the impostor syndrome?

Andy: I think that one of the critical aspects that’s a cure for any of this is to develop what I talked about a sense of clarity. An even-handed perspective on the difficulties and challenges you face in any situation outside your comfort zone. Also an even-handed perspective on the good side as well, on how good you could possibly be.

I think that people often are doomsday predictors when they step in to situations that are anxiety provoking that, “I’m going to be the worst. I’m awful. I’ll never be able to handle this promotion. I’ll never be able to handle this new responsibility,” and so on or they’ll go to the other extreme and say, “I better be the absolute best. I better be a prodigy. I better be unbelievable.”

I think that when we’re in an anxious anxiety provoking situation, we can sway pretty quickly to either side and I think it’s key to have that psychological anchor in the middle to keep yourself grounded, to have that realistic sense that, “Yeah. I’m a novice here. I’m learning. I have a learning orientation. I’m going to make mistakes, but I’m probably also going to have some successes and maybe the fact I’m a novice actually is a benefit because maybe I’ll see things in a way that people who aren’t novices wouldn’t have seen.” I think that that is really critical in terms of curing the impostor syndrome or stepping outside your comfort zone in any situation.

Roger: I’ve encountered it myself occasionally. I was at a conference where I was probably like the only speaker who wasn’t PhD and didn’t have really impressing academic credentials. At first like, “Good grief, what am I doing here?” Much less an opening keynote role, but then I had to reframe it in my mind, “What perspective am I bringing that these folks don’t have and why didn’t they invite me here to do this?”

Once I wrapped my head around that, it also helped me with planning what I was going to say but also say, “Okay. I do have a role to fill here. It may be different than some of these other folks’ roles but I have one.”

Andy: I think that’s true when you don’t have the same professional qualification or background. It could be the case when you’re not the same age. I think nowadays in the workplace, you’ve got a lot of millennials who are in positions of authority. I mean all sorts of situations where people feel that they’re outside their comfort zone and I think that is key in your story is a really good one.

Roger: Now, some of these barriers seem like they cut both ways like a morality barrier. How do you know if something doesn’t feel right to you from a moral standpoint or there’s an internal moral conflict going on? How do you know when you should be following your interior moral compassing, “Okay. This really isn’t something I should be doing and I shouldn’t be trying to get comfortable with it,” versus something is saying, “Well, yes. I can sense this moral conflict, but it’s okay for me to try and bridge this chasm and do whatever it is I’m being ask to do”?

Andy: I think it’s a really good question. I think we all have lines. I think companies have lines. I’ll tell you a story. It’s in the book but just for the listeners, one of the people I interviewed for the book was a booker on a national TV show and her job was to book guests, try to be the very first to book guests especially during situations like a big national tragedy.

Let’s say, there was a plane crash and the networks wanted to cover it and she had to be the first to be able to get to the family and get them on the radio and compete against the other networks. She would call these people and they would be sobbing and crying and just in horrible situation, but she somehow had to push through because it was her job.

Obviously, not all of us are in situations like this, but you can have other situations where you have to I begin the story in the book about a woman who had to fire her very best friend from her startup. We’re often in situations like this and I think that it is a question of balancing our own morals against our perception of the necessity and the validity and the legitimacy of what we’re doing.

In her case, ultimately overtime, it was just too much. It burnt her out. She said it sucked her soul. She couldn’t do it anymore and she moved on to a different career. In the case of a woman who had to fire her best friend, she was thinking about the importance for her investors. For the other employees, who had given up their jobs to be able to join her and her company and how this woman, her best friend was actually bringing the company down. It was a very small company.

I think it is really a balance and it’s very personal and you’re balancing many different things. It’s idiosyncratic in some ways. I don’t know if there’s a blank statement.

Roger: Right. I think it perhaps weighing the greater good in the case of the person having to fire her friend. The greater good was perhaps the survival of the company and the success for its investors even though the action itself presents a moral dilemma. I think in the book, you’ve got another good example of an addiction counselor at a rehab facility who would sometimes have to kick a patient out of the rehab facility because they weren’t following the rules.

That creates a conflict because you know that they’re much more likely to relapse into their addictive behavior if you kick them out. In essence, you might be condemning them to this really terrible faith of relapsing and going through the whole cycle again, but at the same time permitting the rule violations in the facility would undermine perhaps all of the work at the facility not to mention not necessarily helping that individual properly.

Andy: I agree. I think that we face situations often at work where we have to think to ourselves what is our perception of the greater good? I think in layoffs, it’s a big issue. Companies often times try to help those who are in charge of conducting the layoffs or firing the good companies with real deep understanding of the legitimacy of their actions because otherwise it can be real emotional turmoil.

As part of my work, I have interviewed over 50 managers and executives about their experience performing layoffs and understanding that greater good in a real authentic legitimate way is so essential to have that psychological grounding when you’re stepping into a situation where you in that case have to cause real pain to someone.

Roger: I think I’ve certainly seen many of those situations in corporations where the person has not been well-trained or well-grounded, and by identifying with the person that they’re laying-off and saying, “Yeah. This doesn’t make any sense to me either. I’m probably going to be next. Be glad you’re getting out now. Be tough for later.” It’s not really serving the purpose of the corporation very well.

Andy: Or by the way, it’s not serving the benefit of the person being laid off either, frankly, in that situation.

Roger: That’s true too because often … Of course it depends on the circumstance, but often if it’s more of a termination due to the fact that if it isn’t that good then you may be well doing that person a favor by getting them into a situation where they can perform at a high level when they’re not performing and probably not capable of performing in whatever they’re doing now. It’s hard to really put it in a totally positive context if you’re firing somebody, but often that transition will help them in the long run.

Andy: Speaking of firing, one of the stories in the book that just always has stuck with me and this about how even if you understand the greater good, firing someone or letting someone go or stepping into a situation like this can just be so hard even for those of us who are fairly experienced. I don’t know if you remember this story where there was this very, very senior manager at a Fortune 500 company and he had to layoff someone who he had hired a couple years earlier, knew this person well, had been to their house for barbecues and so on.

He felt very confident. Perhaps probably overconfident about his ability to pull it off. An HR manager had suggested that he work on the script that the company had developed, but he said, “No. I don’t need it.” He took it on his hand, but he said, “I don’t need it.” The person being laid off walks in the room and the senior executive looks at him and in that moment he just freezes.

He realizes that the guy walking in the room knows what’s happening. He then knows what’s happening. He starts to become flooded with emotions. He hadn’t prepared. He was overconfident, and he freezes, and he clutches that script in his hand almost crumpling it. You hear the paper and then he just robotically opens it up and reads from the script and literally reads. Looks down and reads, doesn’t make eye contact with the guy being laid off.

I mean, talk about undignifying in a way, but really as a result of how unbelievably, emotionally overcome that senior executive was and how he didn’t anticipate the difficulty of doing this. That’s an extreme example, but that’s an example of stepping outside your comfort zone for sure.

Roger: What are some of the techniques that we humans use to avoid getting outside of our comfort zone?

Andy: We’re really good at it. We do it in a lot of different ways. The obvious one is just to say no to it, to rationalize it away. “Oh, that speech I was asked to give. No, I can’t do that. It’s not that important for my job or my career to give speeches.” We might only do part of the task like delivering feedback. We’ll deliver a part of it but not the whole thing which makes us feel a little bit more comfortable. We might pass the buck.

As a small business owner, I’m awkward, I’m uncomfortable at networking events, making chitchat like we talked about earlier. You know what, I’m going to have my assistant go instead of me. Even though it should be me representing the business, I’ll let her go instead. I’ll let him go instead, whatever it is. I found this a lot with entrepreneurs, they’ll tinker and avoid and procrastinate.

They’ll try to perfect, and perfect, and perfect what they’re doing until not put it out there in the world because how fearful it is to put that incomplete thing into the world when in fact that’s what you need to do to get the early feedback and in the meantime other people with more confidence and more courage put theirs out in the world and they get a head start. I mean, there’s a range of different ways we avoid, but if you do a thorough, honest, psychological accounting of yourself, you’ll probably come up with a lot more.

Roger: I think procrastination is huge because it’s so easy to do. You’re not saying, “I’ve got to make this difficult phone call.” Instead of just saying, “Well, I’m not going to make the phone call,” which would then create some kind of conflict that, “Well, I know I’ve got to make it.” You can always put it off, “Gee, it’s almost the weekend. I’ll wait until Monday and then, oh, they’re probably busy because it’s Monday.”

Andy: Exactly.

Roger: You can go on forever like that.

Andy: Exactly. We’re good at rationalizing too. We’re great at coming up with explanations for why we should procrastinate, why it’s perfectly legitimate as you said.

Roger: You talked about this cycle of avoidance that the more we avoid something, that just simply amps up our desire to avoid it more. Explain how that works.

Andy: It’s like a snake. You’re afraid of snakes. You avoid snakes. By the way, there’s an upside to avoidance which is that’s temporary relief. You don’t have to actually confront the snake or I mean, it’s a metaphor. Let’s say the snake is networking or delivering bad news or whatever it might be, but the thing is that overtime that snake whatever that thing is that you fear, it doesn’t diminish in its power or in its fear.

It increases the more you avoid and so that creates a vicious cycle. The more you avoid, the more the thing that you’re avoiding becomes worthy of avoiding that much more. It’s a very difficult cycle and we all get into it.

Roger: It seems like avoidance is, again, one of those things that has a dual nature. Any number of books by management experts or life coaches tell you that if you don’t like something or you aren’t comfortable with it, then you should eliminate it, you should outsource it, you should delegate it. How do you determine when that strategy of saying, “Okay. Yeah, I’m really not comfortable with this so I’m not going to force myself to do it. I’m going to find some other way of getting rid of it by giving it to somebody else,” or saying, “Yes. I’m simply not going to do it,” or when you should actually say, “Okay. Yes, this is outside my comfort zone but I really need to do that”?

Andy: That’s a good question. I think there’s a lot of … I mean there could be reasons for you in your own personal and professional development or there could be reasons for the company as well and sometimes you need to balance both. There’s a story in the book for instance of a small business owner who was terrible at sales.

He was uncomfortable at sales and terrible at sales. It turned out that there was a lot of time pressure in his industry. He had to start selling quick and he could have tried to embark on this process of stepping outside his comfort zone, but he realized that for time’s sake and for the importance of his business, he actually ended up hiring someone as you said.

I think in a lot of other cases that ends up being an excuse for us not to actually grow personally and professionally. One question that I often ask people when I’m working with them or when I’m teaching them or when we’re talking about stepping outside your comfort zone is if you can imagine the situation you’re talking about, imagine that you could somehow magically erase the anxiety that you experience.

Imagine it went away. Is that thing that we’re talking about something that you actually would want to be able to do? Sometimes we simply don’t have interest. It’s not something that’s important to us. It’s not important to our personal or professional development. In that case, maybe it is something you outsourced or maybe something you get a partner to work on, but in a lot of cases, when people answer that question for themselves, they think to themselves, “Hey, you know what, if I’m really being honest with myself, this is something that would actually help me.” I think that’s where you start to have the courage to embark on the change.

Roger: It sounds like the criteria, one, would be is this something that would be personally good for you to “fix.” If you hate accounting and your business partner is really good at accounting, then maybe it’s fine to say, “Okay. I want my business partner handle that part of the business and I work on sales,” but if you stand back and say, “Okay. Look, I really need to understand the financial picture of myself. I have to work on this and put aside those fears,” but then the other thing is whether it’s going to be effective like, “You’re part of a university and these days the job of the university president is fundraising.” That’s a primary job.

It seems like anyway at many institutions. If they were put in that position, and really didn’t like asking people for money, they could delegate it to the chancellor for development or whatever the university has as their head fundraising position, but they simply wouldn’t be as effective. The hedge fund billionaire is probably not going to return a call from the development director where they might return a call from the university president.

Andy: Exactly.

Roger: In that case, they need to get out of their comfort zone and do it or find a different job.

Andy: For sure. If you’re a university president, find a different job. I think in that particular case, that’s an issue of fit too. I think that there are … Whether it’s a university president or a dean, fundraising is critical and if you’re not doing a proper job search, if you’re not searching for the right candidate and hiring the right candidate, that’s a mistake actually if the people are doing the hiring as well.

I think that in a lot of cases, it’s not as clear cut. They talk about this, VUCA world. Volatile, uncertain, chaotic and … I forgot what the A is actually. Do you know what the A is?

Roger: I don’t recall. I’ve heard that though.

Andy: You get what I’m saying. There’s a lot of change. There’s constant change. All sorts of kinds of change, and that individuals, and organizations have to develop all the time so the jobs that you have today, aren’t necessarily going to be the jobs that your people are going to have in two years from now. People are moving up. They’re moving in different positions, different roles, different tasks, different responsibilities.

That’s really a question of personal growth, personal and professional growth. You’re not going to be able to hire someone for a new job immediately as that job develops and changes. You’re going to have to take the human capital of people that you have and help them learn to grow and develop and that’s where acting outside your comfort zone is so critical.

Roger: If we’ve gotten past the first hurdles, we’ve identified that we are avoiding something that we really should be working on, are there some simple things that we can do to change our behavior?

Andy: Yeah. That’s the whole core of the book is about. It’s about giving people the tools, the skills but also the courage to be able to do it. I found across all these professions and all the people that I work with and these were managers, entrepreneurs, doctors, teachers, lawyers, baristas, actors, goat farmers, all sorts of people and all sorts of professions.

I found that it all boils down to three things. The first was conviction. We could talk about these or I could delve in where you want me to. The second one was customization and then the third was clarity. Conviction is basically finding a way to say yes when every bone in your body is saying no. It’s having that deep sense of purpose.

Almost like giving yourself psychological permission to fight through that tendency to avoid. It’s the antidote to avoidance and it’s very personal. What’s going to give me conviction to give it a go is different from what’s going to give you conviction. In some cases, you realize this is the right thing for you to do or it’s a necessary thing for you to do.

Maybe you realize that overtime this will make you feel good about yourself if you do this. I interviewed rabbis and priest and in some cases, people used the idea that this is my calling as their source of conviction to fight through discomfort, and there’s some really amazing stories in the book about that too. That’s conviction. That is critical. That’s the wind behind your back to actually give it a go.

Roger: Let me jump to one last question, Andy. We’re at the beginning of a new year and I’m sure many of our listeners have some kind of a plan to do things differently or accomplish more in that new year. It’s what you’re supposed to do. What advice would you give them?

Andy: My advice would be-

Roger: Other than buy your book which would be a great starting point.

Andy: Call me, email me. I think to come up with a plan and a reasonable plan. I think that plan should entail things like, for instance, to do an honest psychological accounting, sort of as we talked about before about what the challenges really are for you and your situation, and how, and maybe why you think that you’re avoiding. I think it’s important to also do a psychological accounting of where your source of conviction is. Why for you this particular thing that you like to work on is critically important for you?

Really own that and understand it. Then I think the other thing would be to develop a plan in terms of creating just right situations for you to ramp up to learning how to do this. If you’re afraid of public speaking, and if you decide that you know what, I’m going to start speaking in front of 7,500 people. You’re probably going to go into avoidance overdrive.

For those of you who are parents out there, you’re probably familiar with the idea of just right book for your kid. It’s just right there. It’s what they need. A little bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. That’s what you need to do figure out steps along the way, opportunities to practice that you can hone your skills, develop that sense of confidence and self-efficacy which can then propel you forward.

I mean, that’s my basic advice and the other thing I’d say is that acting outside your comfort zone, it’s not rocket science. It’s not rocket science, but it’s also sometimes not as easy as it’s portrayed on the internet. Just take a leap, go for it. Of course that’s important, but I think it really does take more than just taking a leap, it takes effort, it takes some planning, it takes some courage. That’s really the purpose of my book is to really give people concrete tools and insights to be able to make it work.

Roger: That’s great advice. Let me remind our listeners, we’re speaking with Andy Molinsky, author of the new book, Reach: A New Strategy to Help You Step Outside Your Comfort Zone, Rise to the Challenge and Build Confidence. Andy, where can audience members find you and your content online?

Andy: My website which is www.andymolinsky.com. Feel free to connect with me there on social media and the book is available everywhere books are sold.

Roger: Great. We will link to your books at Amazon and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast and we’ll have a handy PDF text version of our conversation there as well. Andy, thanks so much for being on the show.

Andy: Thank you. I really enjoy it, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.