We would all love to do less and get more done, but the question is: how? Morten T. Hansen is here to give us the answer based on his extensive research.

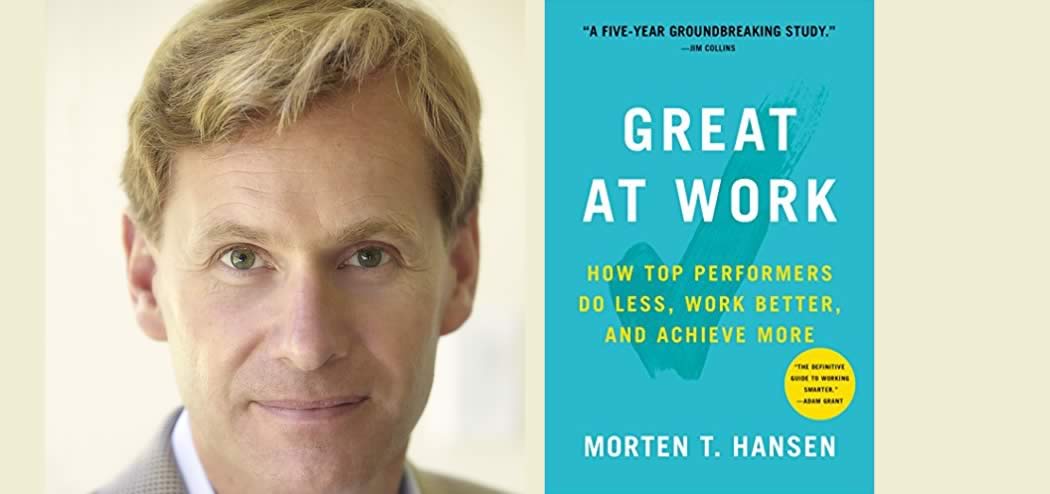

A management professor at University of California, Berkeley, Morten is the coauthor of the New York Times bestseller Great by Choice, and the author of the highly acclaimed Collaboration and Great at Work. His research has won several prestigious awards, and he is ranked one of the world’s most influential management thinkers by Thinkers50.

In this episode, Morten shares key behaviors that stand out among top performers, as well as tips for changing your habits to improve your own productivity. Listen in to learn how to make the most of your time, what to avoid in the workplace, and more.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The crucial skill you need to master if you want to be a top performer.

- What good performers focus on.

- Why trying to do everything to please customers is actually harmful.

- How to avoid making bad decisions.

- Why most meetings are a waste of time.

- What you can do to find purpose and passion in your work without changing jobs entirely.

- The most effective way to change habits.

Key Resources for Morten T. Hansen:

-

- Connect with Morten T. Hansen: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: Great at Work: How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More

- Kindle: Great at Work: How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More

- Audible: Great at Work: How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More

- Amazon: Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck—Why Some Thrive Despite Them All

- Amazon: Collaboration: How Leaders Avoid the Traps, Build Common Ground, and Reap Big Results

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. If you’re a regular listener you know that we like our guests to offer advice that’s based on evidence, not just their personal experience or common wisdom. This weeks guest is ready to do just that. Morten Hansen is a management professor at the University of California Berkeley. He’s a veteran of the Boston Consulting Group and among other accolades Morten was ranked one of the worlds most influential management thinkers by Thinkers50. He’s the co-author of the New York Times best seller Great by Choice, and his new book is Great at Work: How Top Performers do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More. Welcome to the show Morten.

Morten Hansen: Thank you very much Roger, glad to be here.

Roger Dooley: Great, well doing less and getting more done is something we’d all like to experience Morten, but before you tell us how to do that, set the stage by describing the research that underpins Great at Work.

Morten Hansen: Yes, I was interested in the question why do some people perform better than others at work, and if you look around there’s no shortage of advice, there are probably thousands and thousands of books and hundreds of pieces of advice. I wanted to do something different, I wanted to base it in evidence. I said, “Okay, as an academic how do I research that?”

What I did is that I collected a sample of 5,000 people, and it was a five year research project where we did a statistical analysis linking work habits to performance and we also did in depth case studies of 120 people to understand at a more detail level what they actually did. This sample has avoided the sample selection problem we have, which is that you only study successful people. We didn’t do that at all. We studied successful, medium success, and also poor performance, and we wanted to see what differentiates the top performers from the rest.

Roger Dooley: How did you conduct this research? That’s a nice big sample size and it’s great because so many books are written purely based on opinion or hey this stuff worked for me so it’s bound to work for you, so it’s good to get one that has some scientific underpinnings, but how did you conduct this research with such a large sample size?

Morten Hansen: At first we started out with some hypothesis, you got to start somewhere and turn out that a number of them were incomplete or even inaccurate but you’ve got to start somewhere. Then we decide a pilot of 300 people and we tested these hypothesis on this pilot sample, and that was a survey instrument that we had developed about 100 questions that was administered to these people. Instead of just doing self-report we also had bosses and subordinate of the sample, so we’re not relying on self-report only here because that would bias the sample.

Then after the pilot we decided, okay now we can tweak and add some more accurate hypothesis. Then we decide another survey instrument and then we administer that for 5,000 people. You can’t follow 5,000 people around in the office for several years, that’s practically impossible, but you could administer this survey instrument to them or to their bosses and subordinates, and then on that basis we got back information and then we spent two years basically running statistical analysis on that data set. In addition we did this deep dive into use and that’s where we formulate the essence of it.

Where I started out, some kind of ideas I had, conventions you could call them about what it means to work well were really overturned, and I personally learned a lot in the process.

Roger Dooley: That’s great, we want to hear what your biggest surprise was but I wanted you to explain a little bit what went into this because I have a lot of respect for podcasters like Tim Ferriss that talk to high performing individuals and dig into their habits and so on, the way they approach problems, but sometimes it’s hard to see if that advice really scales to a bigger audience. Something worked for a top Navy Seal but that may not be the same approach that works for you or me, and often people too misattribute what is important to them. They may say well I start everyday by meditating for 15 minutes and that keeps me focused for the rest of the day. Maybe it doesn’t or even if it does, again that might not work for somebody else, so it’s great to see this kind of statistical base underlying your work.

Morten Hansen: I should add that we looked at wide samples, so it wasn’t concentrated in high tech industry only or in certain professions. We looked across industries and we looked across roles in companies because you could do the study on salespeople only but then really you only have advice for salespeople. We wanted to broaden the sample and that was one of the goals, hence you needed 5,000 people, you couldn’t just study a couple hundred.

Roger Dooley: One question I do have about the data, could there be bias in it’s sort of a halo effect? In other words say I’m a supervisor rating an employee, I’ve got this employee that I really like, I consider them to be my highest performing employee, could my answers on some of the questions about their work habits and so on, where they score on this various criteria that you had, could that be influenced by that? Same thing if I have somebody who I don’t think is very good I’m going to rate their work characteristics more poorly rather than purely objectively?

Morten Hansen: Yes, that’s always the problem, we got to look out for that. That depends on how well you design your study, so for example, we would ask in the survey instrument you kind of have to design the questions cleverly. First of all you ask multiple questions to tap into one dimension, and then you ask negative questions. If I ask a question about focus, I also want to ask a question about lack of focus or spread too thin, that is a neutral question so that you don’t bias the answers. Then you look at the responses and if there is a halo effect you get inconsistent responses, so it’s really about designing it according to the best survey instrument design that we know. That’s one way.

One way you can check for the halo effect is if everything is positive you probably have a halo effect. We got a lot of negative relationships in the data set, which means that they weren’t really responding only to halo effect. There’s also when you look for information you’re going to try to get information and data and not opinions. The question has to be asking, so is this person working in such and such a way as opposed to do you think the person is focused, that’s a very subjective answer.

Roger Dooley: Right, and I’ll leave the methodology for now but for those readers who want to dig into it there is an appendix to the book, a lot of detail about how the survey was conducted, even the exact questions that were asked and so on so that you can dig as deep as you want in that.

Morten Hansen: Can I just say one thing Roger before we move on from that, and we call the survey instrument is collecting the data, but a survey in and of itself doesn’t provide any answers. It is as a research when you start looking for relationships and hidden relationships in the data. Because what I’m after is get some data on work habits, and then I’m trying to correlate or relate that to their performance scores, and that’s where you get the interesting insight because I’m not asking the person in the data, the respondent to do that, I do that myself. That’s why we spent basically two years statistically analyzing. We found some really interesting correlations or relationships that we hadn’t expected.

Roger Dooley: Great, so Morten early in the book you say there are seven work smart practices, as you call them, and graph individual scores. This is a graph with thousands of dots on it against performance ratings, and what it shows is pretty remarkable. You’ve got a line, well I mean there’s a lot of scatter in the data of course, but it’s a very consistent sort of scatter that you can show that there’s really a huge amount of correlation between these practices that you identified and how people’s performance was rated by those around them. Were you surprised, I guess to some degree, the data’s compelling because you teased out these relationships as part of the study, but were you still pretty surprised by how the graph turned out to be such a clear indicator?

Morten Hansen: Yes I was because basically seven practices, seven key practices, explain about two-third of the difference in performance among these 5,000 people so it explains a lot. That means that one-third we’re not able to explain and that’s always the case. This doesn’t explain everything. Talent and luck and maybe other factors play a role here of course, but it’s interesting to note that a few key practices explain a lot of why some people are just better performers. We don’t need to follow 200 pieces of advice, we really only need a few.

Roger Dooley: I found it really fascinating, the first one is “do less then obsess,” and of course that’s something that the do less part I’m sure a lot of people would say, “Okay, well I can manage that.” Explain how that one works.

Morten Hansen: Yes, actually I think it is in straight forward principle very hard to practice. I’m struggling myself too to implement it. The “do less then obsess” principle has the follow ingredients. First, do less means the top performers are focusing or choosing to focus on a tiny set of priorities, and once they have done that they then obsess, they go all in and apply all their intense targeted effort at those few things. That’s a principle. Now to do that right there are a couple of things you need to do. First of all it’s the question what should you focus on? The answer is that they focus on what I call value creation. In other words they look at their job and say how can I create the most value for my organization, for customers, suppliers, and other people in this job? It may not just be your job description as it’s given to you, it might be other things or tweaks into your role, so you need to start changing how you do your work in order to create more value.

Once you answer that and you actually on down this road of focusing on those few valuable activities and applying a lot of effort, what usually happens then is that somebody, maybe your boss, maybe your colleagues would come to you and say, “Hey, could you do so and so in addition?” In other words they’re asking you to do more, and that’s when you have to say no. Stay disciplined on the course because it’s so easy to take on more things and then you’re unfocused again. These are a set of things you have to do, and those top performers who do this this is the principle that matters the most. They rank 25 points higher in the performance ranking than those who cannot do this principle. In other words, let’s say you are in the 70% percentile, top 30% performer and you don’t do this principle but then you start doing it, you would likely then go 25 points higher, which is in the 95% percentile, in other words top five performers. This is the difference between being pretty good and being outstanding.

Roger Dooley: You know this is something I don’t recall which author, some kind of similar conclusions about cooperation and it highlights the most effective people were those who were cooperative but weren’t pushovers for their coworkers or whoever was asking them to do stuff. They found that balance between being part of the team and ensuring that the work was getting done properly, but not taking on everything that was asked of them because those folks just got bogged down in the minutiae.

Morten Hansen: Yes, I think you might be referring to Adam Grant’s book Give and Take. It’s a terrific book by professor Adam Grant at Wharton Business School. Yes, he found the givers are really the ones who perform the most best, but there are also givers who don’t perform very well because they are pushovers, they are like a doormat, they say yes to everything. You’re not just giving of yourself but you’re not really getting your work done. There is a difference there. This ability to say no is really crucial if you want to be a top performer. It’s something that many people, including myself, struggle with. It is very difficult to push back at your boss.

Roger Dooley: Right, and I think even for those of us who may be our own boss, entrepreneurs and authors and so on, can fall victim to the same thing because there’s always somebody asking for something. They say, “Well gee, that would be somewhat helpful for me or that would be good for the business to do that,” but you have to stand back and say, “Okay, is this really going to be important for what I absolutely have to get done that’s going to mean the difference between success and failure, or is this just sort of like a nice to do if I had infinite time?” I know personally I find some of those things that I might otherwise agree to, fall into that category that a yes would be nice, but it’s not critical to the mission.

Morten Hansen: I think it might be even more difficult for an entrepreneur or a small business, and so there’s a terrific story and example in the book about an entrepreneur called Susan Bishop who leaves her executive search firm to start her own firm out of New York. She’s a specialist in media, so she start out this firm and she has maybe five people on her team. In the beginning they do well and then they get requests from other customers, clients in financial services, in consumer goods, lower level searches, not in New York but some other place, and before you know it she’s spread too thin. She says yes to everything. She had gone to a marketing seminar she said where she learned that you’ve got to please your customer, and so her motto was do whatever is humanly possible to please your customer. That makes a lot of sense, but it also meant that she said yes to everything and everyone. Then she lost her focus.

Roger Dooley: Right, and of course this is real business too. I mean not even somebody saying, “Hey, can you attend this meeting,” where there’s no real benefit. Her company was getting more business from new clients and important clients, so one of the hardest things for an entrepreneur to do is to say no to business.

Morten Hansen: It’s extremely hard and she said I got to pay the bills. I got people to pay, payroll to make. Yes of course, so that’s why she said yes. The problem in the medium term was that she was eroding her focus and her real competence, and she found herself spread too thin. Now the business grew but her profit margin was half of what it should have been because these were into new areas where she didn’t have the expertise, she had to build a network, but the databases to do them, she ended up with difficult searches that took twice the time they should have taken. It wasn’t a recipe for great success, and then she had an epiphany. Now she said you know what, I’m going to apply a set of rules that are going to sharpen this business. I’m going to go away from all this do more and please every client, to find my segment, go all in on that segment, in other words do less and obsess, and then I’m going to do so well in that segment then I’m going to get a lot of business in that one.

She established those rules and then it was tough, of course, because now you say no to clients. She related a great story where she had a Coca-Cola approaching her with a very big deal, $250,000 in one search for a set of their positions. She’s running a small business, $250,000 it’s real money. It was outside of her segment of media that she had decided to concentrate on, so she told me she went into this meeting, there were two senior guys sitting there from Coca-Cola in their headquarters, and she went out there and she says, “You know, my knees were knocking against each other, I was so nervous.” She said, “I had to say no to them.” Sort of toughest thing she did. You could say well, you know, how can you say no to something like that? But she did because she knew it would have distract her. For a while it was tough going because she was going through this valley of death as some people call it, which is you decide to concentrate and focus and you’re saying no to income basically.

Then she started getting traction in media, and she did such good work that more and more media companies started approaching her, and now the business took off. It’s a perfect example entrepreneur if you said yes to too many things, changed approach, and was more successful after that.

Roger Dooley: Changing gears to one of your other practices, you call it passion and purpose, people, especially new college grads but certainly people in all levels of their life and career are told to follow their passion, which I guess that isn’t totally bad advice rather than hey you ought to pick a career that pays pretty well even if it really bores you to tears. That doesn’t sound too attractive, but what are the pluses and minuses of pursuing a passion?

Morten Hansen: Yes, so I think that both of those obviously I think are pretty bad advice. Ignore your passion, go for the safe and tried, it’s going to be a life of drudgery and misery. On college campuses all over and if you read Ted Talks and many other places, I saw on a front magazine at the airport the other day, it said follow your passion, do what you love as the front page advice. If you’re going to take that literally what it means is that you should let passion dictate what you do regardless of other considerations. That’s dangerous because it takes you down a path where the only thing you’re concentrating is what excited you, regardless of whether you are making any contribution to others, to your customers, or anyone else.

That’s the dangerous part of passion. What I have found is that we should not follow our passion, we shouldn’t ignore our passion either. We should do a third thing and that’s what the top performers in my data set did, they matched passion with purpose. The purpose is defined as do what contributes to others, in other words start as simple as saying I’m going to focus on what makes a good contribution to say my customers, or to my organization, or to society, or to environment. It can be a range of things, but notice how purpose is about what you can do for others. Whereas passion is what I can do for myself, is hedonistic quality, is about what excites me. Whereas purpose is about what you can create value for others. Why is that important? Because people pay for that.

Roger Dooley: Yes, Morten I think it’s important to point out that like you think of a job with purpose and obviously somebody in healthcare or teaching or whatever can say well that’s pretty obvious, but what you point out in the book is that it can really be in any environment, even in organizations that aren’t saving the world or saving other people, you may still be helping customers, maybe helping your coworkers, or the organizational mission.

Morten Hansen: Right, exactly and we have a little bit of a wrong view of purpose. We think it’s help alleviate poverty in the world. That’s purpose too, but most jobs have purpose. I have a great story of a concierge at a hotel, and I’m sure we think that’s not really a meaningful job. This woman, Genevieve, she is very passionate about her job but she also this this as purposeful. She’s helping people coming to hotel to have a good experience in Quebec, Canada where this hotel is and she see that as purposeful. She is very, very good at her job, in fact she’s a member of this very exclusive concierge club of the world that’s called The Golden Key, and you only get admitted if you are outstanding in your job.

She is excited about her job, she likes it interacting with people, that’s kind of the personality she is, and she see it as purposeful. It’s about what the person in a job finds meaningful. It’s not about what we think about the job, and so you got to find that in your own job. What is purposeful here and strengthen the purpose, what better contribution can I make to others?

Roger Dooley: Right, well that’s a good point. If somebody is in a position where they may not be highly passionate about the work and their purpose isn’t really clear. Now obviously one thing they could do is change jobs completely and try and find both someplace else, but within that environment are there some things that could be done to maybe improve without jumping ship?

Morten Hansen: Yes absolutely, I think that’s kind of the key of that finding in that chapter, both in terms of passion and purpose. You could change your roles along the way. I think of purpose as having three steps in the ladder, and the first step is what I call this thing about value creation. Value creation is about creating more value for others and doing better. If I’m an entrepreneur, you sit down and say, “What value am I creating for my customers? Am I truly creating value? Am I just delivering a product?” Value selling and solution selling is kind of in that direction. I’m trying to solve a problem for the customer, and one good technique there is what’s the pain point that the customer has and can I actually solve those pain points for them? Now we’re creating new value.

That’s purposeful, and then you want to have the second ladder is what purpose is meaningful to me? Do I actually personally find this meaningful? You may not, and so you got to find what you find meaningful. I wouldn’t like to be a concierge personally but others might like Genevieve. Then there’s a third step on the ladder, which is more the societal contribution. Am I helping the environment, am I helping the communities? Of course healthcare and other professions do that, but you can find that in other professions as well.

Let me give you a very brief example on the last part there. The guy who comes and cleans my carpet in my home, he runs a small carpet cleaning business in San Francisco. That doesn’t sound very purposeful, but then he realized if I switch to non-toxic, environmental friendly cleaning products, I’ll first of all help the environment a bit, and secondly those homes will be non-toxic, they will be easier. He made that switch, it was a small switch, it didn’t cost him that much extra, and it gave him a little better contribution to society. That was one little thing that he did.

Then he did another little thing that was helpful for us as customers. He said, “You got some stains on your carpet. You don’t need me to come back to clean those, those are few spots that will happen during the year. Maybe I can come every year. Here’s a solution I’m going to give you to you for free, a bottle, and let me instruct you how to do this properly.” He showed me how to clean up those stains that maybe my cat left behind. Now if you think about it he helped me, he created value for me, but he sort of also took himself out of that business because I don’t need to call him to come back and clean those stains, but he created value for me. Indirectly he benefited because I said, “Wow, this guys great. I’m going to have him come back next year, I’m not going to switch.” He created a very loyal customer base, but he thinks value and purpose in a seemingly trivial business but it isn’t, not for him.

Roger Dooley: That’s a great example Morten. If our listeners think about their own roles, even if they don’t see this amazing purpose immediately there are probably some little things that they could do. Speaking of little things Morten, being a West Coast, you’re probably know B. J. Fogg at Stanford, one of his key principles for habit development is to start small. You’ve got these seven practices that you recommend and you two talk about sort of the same thing. He would say don’t set out to form a habit of walking an hour everyday because you’re going to do it for a couple or three days and then you’re going to get tired and quit, but instead commit to five minutes. If you can just get five minutes of walking in, over time it’ll become a habit and you’ll feel comfortable going to 10 or 15 or longer on some days, or if you’ve got a day that’s really busy maybe you only will do it for five but that’s how to develop habits. Even though you’re not necessarily talking about habits exactly, you have sort of the same philosophy right about small steps?

Morten Hansen: Yes absolutely, I know his terrific insight and research there and he means start really small. There is a benefit of starting small. First of all we’re not going to make wholesale changes and it’s more difficult, so instead of saying I’m going to focus now, that’s my New Year’s resolution is to be very focused. You could say let me start shaving away things, I’m going to start saying no to a few meetings or a few activities. You just slowly getting more focused over time and you don’t have to do just binary from zero to one. That’s why a lot of New Year’s resolutions frankly they don’t work because you’re going cold turkey. You’re saying I’m going to quit everything that is bad, I’m going to start everything that’s great. I’m going to be in the gym everyday and it was zero before, it doesn’t work.

The other though is starting small, which is interesting. Small changes, if they’re really well designed, can have very big impact. If you find the right small changes they can have a very big impact. I mean this is the idea of nudges, a well placed nudge, a small intervention, can have a disproportionate impact and that’s true for entrepreneurs, managers, your individual contributors. If you can find that little lever it can make a big difference. If you start small with the right things it can have a big difference.

Roger Dooley: You mention meetings and that sort of ties into your fight and unite chapter. I think everybody complains about meetings. Do businesses have too many meetings or do they do them wrong or both do you think?

Morten Hansen: Both, I mean I think that’s what the data show and if you ask people about the productivity of meetings people are usually very negative. The problem is that we start out with bad meetings. Now what is a meeting for? If you’re asking five people or 10 people to join you, it doesn’t matter if you be an entrepreneur, it could be a big company, it doesn’t really matter. Meetings are for one thing and one thing only and that’s debate. It’s a discussion, it’s drawn a collective wisdom in the room to debate an important topic in order to make a good decision. Now they could be that the leader makes the decision, it doesn’t have to be consensus, consensus is not necessarily a good thing, but you are having debate.

If you ask people to join a meeting just for status update, well you know what? That could be put in an email. If it’s for some other purpose you don’t need a meeting. Then the question is are we having a good debate? Here people violate that principle left and right. First of all what does it mean to have a good debate? First of all you got to have the right people in the room. Secondly you got to set up an agenda in advance that is focused. Third, people have to come prepared to the meeting. If they haven’t read the preparation material how can they have a debate over topics that they don’t know anything about? Fourth, you need to have a discussion that is productive. People need to be able to speak up. Your managers come into meeting and they start the meeting by saying, “This is what I think we should do. What do you other guys think?” Well you set a bias in the room, people are just going to be biased in direction to what you just said because you are the boss.

You got to start with an open ended question. A lot of people get all of that wrong. We know that from the data in my study, so if you have a bad meeting what do you do then? What’s a consequence of bad meeting? This is where it gets perverse. It’s a followup meeting to continue the debate that you didn’t have in the first place. Bad meetings lead to more bad meetings. We have incredible quotes of people saying, “You know what, we just have one incomplete meeting that leads to other incomplete meetings and then we got a third one, even a fourth one sometimes. It’s a waste of time.”

Roger Dooley: Right, and the key thing is to get other opinions out there because I do believe that is one of the biggest failures. I mean I’ve certainly seen it happen enough. Fortunately I don’t spend that much time in corporate environments these days, but once it’s clear that there’s some momentum behind a particular decision that the bosses pretty much either decided completely or is heavily leaning in one direction, there is a great tendency for everybody else to just sort of fall in line. Even those that might actually have some good information or have reason to believe that that decision isn’t the best decision, it’s like well why fight the boss.

Morten Hansen: Right, but I think that’s true in small startups and entrepreneurs. Because you got one founder, you got one strong person and it’s hard for others to push back, but I think if you’re in that role, if you’re the founder or the leader of a small business, stress test your own thinking. I mean that’s what it means. Find people who are able and willing to speak up against you and stress test it because your business on the line. You make a bad decision because you haven’t thought of something. Well, you know, you want to have that stress tested before you implement such a decision.

I think in large companies it’s perhaps more political, that’s why people don’t speak up. They have agendas so that’s a different reason and people don’t, lots of people don’t.

Roger Dooley: Right, and I think certainly many people in a corporate environment, having the corporation succeed is not necessarily their first goal. I mean they certainly don’t want to see it fail, but surviving their particular situation or getting promoted or whatever, that ends up being the primary goal and if you can take an action that might not be in the interest of the corporation but will increase the chance that you will be around next year or get promoted or something like that, in many cases that’s exactly what happens. Of course, it might be optimal for that individuals but sort of sub-optimal for the organization as a whole.

Morten Hansen: We see that many times and people are pushing their own agenda and they may not be in interest of the company. My good friend and coauthor Jim Collins, he talked about that in a really great way in the book To Great, when he talked about level five leaders. Which are leaders that are able to subordinate their own agenda and egos in pursuit of the common goal, what’s best for the company. Unfortunately we see a lot of non-level five leaders that are first and foremost thinking about what’s good for them and that might not be what is good for the company or the business they lead. Then we get into these kinds of situations.

Roger Dooley: There’s probably two modes of failure there. One is the leader who just believes that he or she is invincible because she created this great company and therefore knows more and is smarter than everybody else. Then the other one is where it’s actually, they may be across purposes where they’re trying to maximize the value of their stock options for next year.

Morten Hansen: Yes, and that’s a great point and those are two different things. I think on the first one there that you think you are genius and you have been right many times before, that’s why you got where you are. That’s true of a successful entrepreneur or a successful small business or family business. You have been right so many times, but that can be very, very dangerous and that’s why you need to stress test your thinking. Find people around you who are able to speak up in meetings and say, “No, that is wrong and here are the reasons why that is a flawed thinking.” Very, very important otherwise you’re going to make some really bad decisions.

Roger Dooley: Great, well I want to be respectful of your time Morten. Let me remind our listeners that we are speaking with Morten Hansen, professor at UC Berkeley and author of the new book Great at Work: How Top Performers do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More. Morten, how can people find you and your work online?

Morten Hansen: The best place is to go to my website www.mortenhansen.com and let me spell my name. It’s M for Mary, O-R-T-E-N H-A-N-S-E-N dot com.

Roger Dooley: Great, well we will link there and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at Rogerdooley.com/podcast. You’ll find a handy text version of our conversation there too. Morten thanks for being on the show, enjoyed the book.

Morten Hansen: It’s been a pleasure Roger, thank you so much.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.