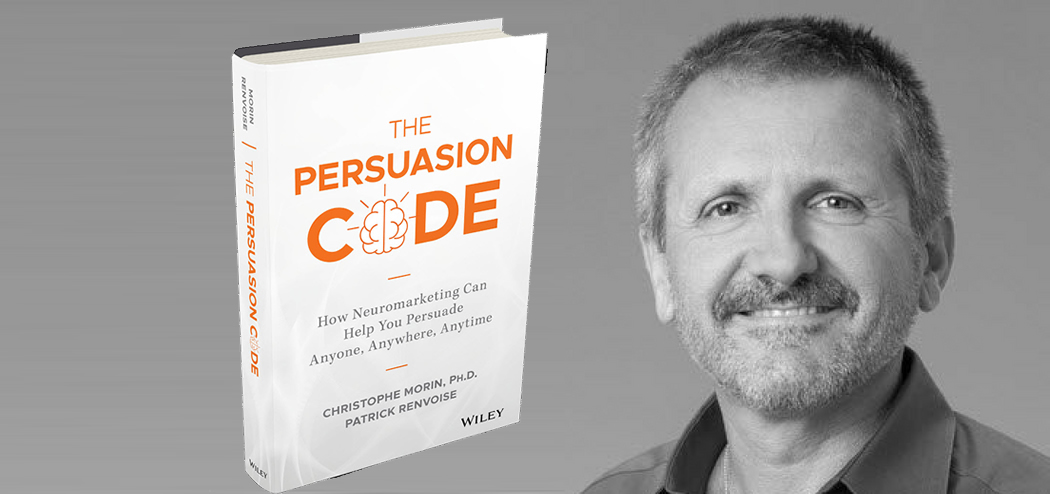

Welcome to the first of a two-part series that will focus on the new book, The Persuasion Code, co-authored by Christophe Morin and Patrick Renvoise. Today we’re speaking with Christophe, who serves as the CEO and Chief Pain Officer at SalesBrain. With a Ph.D. in Media Psychology and over 30 years of marketing and business development experience, Christophe was formerly the Chief Marketing Officer for rStar Networks—a public company that developed the largest private network ever deployed in US schools. He also previously worked as VP of Marketing and Corporate Training for Grocery Outlet Inc, the largest grocery remarketer in the world.

Welcome to the first of a two-part series that will focus on the new book, The Persuasion Code, co-authored by Christophe Morin and Patrick Renvoise. Today we’re speaking with Christophe, who serves as the CEO and Chief Pain Officer at SalesBrain. With a Ph.D. in Media Psychology and over 30 years of marketing and business development experience, Christophe was formerly the Chief Marketing Officer for rStar Networks—a public company that developed the largest private network ever deployed in US schools. He also previously worked as VP of Marketing and Corporate Training for Grocery Outlet Inc, the largest grocery remarketer in the world.

In this episode, Christophe shares his expertise on understanding and predicting consumer behavior using neuroscience. Listen in to learn what it takes to create convincing campaigns and what makes marketing messages really stick.

Learn what it takes to create powerful persuasive messages with @christophemorin, co-author of THE PERSUASION CODE. #neuroscience #psychology #persuasion Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The best predictor of how effective you can become in your ability to advertise or persuade.

- What’s crucial to enhancing and predicting the effect of persuasive messages.

- A big mistake in the neuromarketing industry.

- Six stimuli that trigger the primal brain.

- What caused Christophe and Patrick to write a new book 15+ years after their first.

- Why the concept of pain is central to both of their books.

- The problem with research based on self-reporting.

- What comparative advertising is and why it’s so effective.

- How things are changing on the academic side of how people view neuroscience.

- Examples of how neuromarketing can be used to serve ethical goals.

- How Christophe used neuromarketing to evaluate how young adults respond to public health PSAs.

- What makes persuasive messaging more effective for younger brains.

Key Resources for Christophe Morin:

-

- Connect with Christophe Morin: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: The Persuasion Code

- Amazon: Neuromarketing: Understanding the “Buy Button” in Your Customer’s Brain

- Amazon: Thinking, Fast and Slow

- Vistage

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Today we’ve got the first episode of a two-part series. Both segments will focus on the new book, The Persuasion Code, by Christophe Morinn and Patrick Renvoise. Our listeners will recognize those names as the authors of what is likely the first book on the topic of using neuroscience in marketing, which was Neuromarketing: Understanding the Buy Buttons in Your Customer’s Brain, more than 15 years ago.

Today we’re speaking with Christophe, who is the CEO and Chief Pain Officer at SalesBrain. Christophe’s academic credits include a PhD in media psychology, and he is an expert on the effect of advertising on the brains of adolescents and young adults. The full title of their new book is The Persuasion Code: How Neuromarketing Can Help You Persuade Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. Welcome to the show, Christophe.

Christophe Morin: Welcome to the show. Thank you so much for inviting me.

Roger Dooley: I’m so glad you could be here. You guys have been around in this industry forever, and I think this is a really significant new book, which is why we’re doing it as a two-segment series rather than having you both on at once. Has it really been about 16 years since your first book came out?

Christophe Morin: Time flies when you’re having fun, Roger. Yes, we did create the company in 2001, formally started to deliver consulting and research services in 2002.

Roger Dooley: That’s amazing. It sure does fly. I think I got interested in about 2004 or so, and started writing in 2005. You guys were well ahead of me. That’s really amazing. Since you’ve been in the industry this long, Christophe, let me ask you first, how would you define neuromarketing?

Christophe Morin: I would say that neuromarketing is supposed to create insights that are coming from the measurement of neurophysiological activity. Of course, neurophysiological activity cannot typically be self reported by research subject. For too long, market research and the production of insights on consumers have been based on what people can say and report, which is a very partial and sometimes very biased view of what consumer either think or do when they make certain buying decisions.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think that’s been a theme in the industry for a long time, trying to get below the surface and figure out what people really want, how they really react, when they really are, in most cases, not all cases, but most cases unable to articulate those things or what really motivates them. Would it be fair to say that the basis of the first book is that every customer, including business to business customers, has one or more pain points and often these are not necessarily conscious or rational pain points. They may not be able to describe them or acknowledge them, but an effective sales or marketing effort has to address those first.

Christophe Morin: Yes. It is true that the first book was presenting, we believed, a radical perspective on what happens when people make buying decision and to consider people not as necessarily decision makers, but as organs that are activating certain circuitry in their brains to trigger those decisions. The concept of pain was central to the first book, and certainly is to the second because deeper in some brain structures we call the primal brain, we are on an ongoing mission of protecting and avoiding threats that ultimately we described as pain points or frustrations. So investigating those pain points just through conversations can be a difficult exercise because people cannot necessarily articulate, but if you can crack the code of why people are moving away from certain situation, their fears and their pains and their frustrations, we have found that to be the best predictor of how effective you can become in your ability to advertise or persuade.

Roger Dooley: Hence your title is Chief Pain Officer, although I have a suggestion, Christophe. Have you ever thought about being the Chief Pain Relief Officer? It’s got to be tough to tell a new hire that they’re working for the guy that’s in charge of pain in the company.

Christophe Morin: It’s a grabber, and it’s been quite interesting and sometimes funny to see what meaning people attach to the concept. I have, as you know, in my background been obsessed by the process of decoding consumer behavior and this factor of pain and now we describe it deeper in our book under the whole framework of how anxious we are as human beings. I quote Joseph LeDoux, he’s such a prominent scientist and researcher, in the meaning of our anxiety. I have, you’re right, adopted a title as a result that is quite cryptic but gives me the opportunity to engage in phone conversations from the beginning.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Joseph was a past guest on the show, and a very interesting guy, very accomplished in neuroscience, and great, really the amygdala guy. It’s been so long since you and Patrick wrote the first book. What caused you to say, “Okay, now is the time, after so many years, to do a new book”? Was there a triggering event, or just sort of an accumulation of experience and knowledge?

Christophe Morin: Well, you’re an author, Roger, and I think you’ll understand if I make the analogy of birthing a book, because I have felt the urge to write this second book almost right after we wrote the first one. It took us a fairly long and sometimes frustrating journey to finally put together, not just the premise of a theory which was really what the first book was about. It was never meant to be a pretentious scientific book, and I hope we don’t position Persuasion Code as a pretentious scientific book, but it is far more diligent in terms of laying out a theory on persuasion and to present the evidence that has come from more research papers on the subject of consumer neuroscience or behavioral economic studies that are using now neurophysiological measures.

So there’s been more production of peer-reviewed papers. I’ve wrote a few. We’ve produced our own research. It is not always easy, and I’m sure you know that, that we can share the private data that we create for some of our customers. Neuromarketing is still in many ways considered a strategic advantage, and therefore customers aren’t always eager to share. But I wanted to have enough research evidence, if you will, to make a more compelling and a more persuasive argument around our persuasion theory.

It takes two to three years to publish a peer-reviewed research paper. Therefore, as you know, the industry as a whole has suffered from not having enough credibility and be able to publish evidence that would continue to convince marketing researchers, advertisers, to stop just interviewing and doing focus groups and consider the power of neurophysiological measures.

Roger Dooley: Do you see that changing, Christophe? Because that has really bedeviled the industry. I mean, forever practically there have been folks who just assume that neuromarketing was some kind of a pseudoscientific thing. Neuroscientists spoke out against using the techniques, saying that they weren’t valid, there was no proof, and so on.

Then, finally, a few years ago there was the big Temple study that actually with some rigor showed at least in that study that FFRI could produce valid results. They didn’t have quite as good luck with some of the other techniques, but then again, they weren’t necessarily experts in those techniques. I think that maybe gave it a little bit of credibility, at least as a topic for research, so that scientists could look at it without being labeled as somehow really too far out here, or working on flying saucers or something. You’re closer to that area than I am. What do you think is changing on the academic side of things?

Christophe Morin: Well, I put some blame, to be honest, on the neuromarketing industry for failing in many ways to create more adoption. I think for too long we’ve made this feel too complicated, too intimidating, almost suggesting that if you’re not a neuroscientist, Mr. Chief Marketing Officer, you’re not going to get it. I think it was a really bad mistake because rather than talk about how neuromarketing is performed, which can be somewhat complicated, we should talk about the value of answering research questions that cannot be addressed through normal or traditional market research, such as, “To which extent is your message activating subconscious mechanisms in the brain?” which we all know and the scientific community has completely validated. Are those part in the brain that influence, if not guide or control, conscious decisions? As long as we keep in mind the ultimate benefits and outcomes, which is what The Persuasion Code is trying to do, I do think adoption will grow. I do think that there’s a need for more accountability in advertising effectiveness, and that accountability has not existed for a long time.

Roger Dooley: Christophe, I mentioned Temple University. Are you aware of other reputable schools that are actively working on neuromarketing type projects?

Christophe Morin: I am on faculty for Fielding Graduate University, and I have created a certificate in media neuroscience. The popularity of courses more so than research has grown. There are more and more universities, Duke, for instance, is another one, other prominent university that are now looking at consumer neuroscience or neuroeconomics as fields that are worthy of more funding. But it’s all a very slow and too slow process to encourage business people to do something with it.

As you know, most research papers are read by scientists, not by business people. So the mistake, I think, from the neuromarketing industry has been to almost wait for all this research, all these papers, to come out before presenting convincing arguments that these methods that are inspired by neuromarketing insights deliver value, and they deliver ROI. In the book Persuasion Code, we were very lucky to receive permission from many of our customers to share the ROI of their investment, and we hope that part of the story will be more interesting and more compelling than the research paper citations, even though we’ve taken the time to identify 300 scientific citations. Certainly I feel that this book has done what few books on the subject have ever done to provide a compelling resource of research papers.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, there are really a ton of great citations in this, so anybody who wants to dig into a topic more deeply can find it there. But I think that in the book one thing that you’re doing is addressing one of the problems that the neuromarketing industry has had, which is that generally, well, first, as you say, there are not many academic studies out there that you can really say, “Okay, this validates the concept,” but also most neuromarketing companies and their clients will not publish information because they feel it’s proprietary or because even they feel that it will somehow scare their customers.

It’s like, “Oh my God, this company is using this weird brain stuff and that’s scary, so I’m not going to buy from that brand.” Early in the industry there was some of that, and I think that went away quite a bit, although now with all this stuff about Facebook data and so on, I think that some of this slightly justified paranoia is creeping back in, even though the techniques that are used by neuromarketers are not really invasive in any way. They’re just finding out what people like and how they react. I don’t know, do you see that evolving?

Christophe Morin: I do, and the subject of ethics is a real important subject. When I was a founding board member of the Neuromarketing Science and Business Association, I was also the lead author of the ethical code, which is implicitly a commitment from all the members to use research methods that are not messing with privacy, that are not disclosing information that people do not disclose, that are not harming, obviously, in any way the subjects. After 16 years, there’s been no known incident or case of a neuromarketing study that would have violated any form of ethical conduct. So it’s fairly easy to imagine that it could happen.

I’m not suggesting that we should not as an industry continue to evolve and be transparent. I think that’s been the real issue from the beginning, that there were so many questions unanswered, unaddressed, that of course some journalists would find it rather easy to start pointing the finger at the evil nature of neuromarketing. I truly believe, and in the book I do cite some of the research that I’ve done in public health, to improve the communication on very critical subjects. I truly believe that using neuroscience to create better messages can serve a lot of very good and respectful and ethical goals, including promoting ideas and campaigns that could help us be better in all kinds of situations, whether it’s public health or climate change and other themes that need to be communicated effectively.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, actually, in the book you describe evaluating some public health related PSAs for teens and young adults. I guess I’d like to hear how you did that and what you found, but also before that, just a more general question. What about using neuromarketing techniques on minors? Is that okay, or okay in certain circumstances? What do you think?

Christophe Morin: The code that I largely authored was specifically preventing research on minors. Now, in the traditional research community it is a fairly standard practice, and sometimes very useful practice, to investigate minors. But you have to do that through very controlled protocols, including the permissions of the parents and so forth. I personally, in our business, we stayed away from any situation that doesn’t comply with the code, but specifically on the research that you’re asking me to comment, which did not include minors, I wanted to investigate the degree to which brain development could modify the response that young adults would have towards public health messages, anti-tobacco messages, and so forth.

Because a very central part of what neuroscience has revealed is the fact that certain areas in the brain do mature rather slowly. The frontal lobe, which is where we have the best of our attention and decision making, and more importantly, where we make the predictions that are central to our ability to engage into a behavior, the frontal lobes are known to now not be “finished” until age 25. What my hypothesis in the research was, can someone who is less than 25 years of age respond differently than someone who is above 25 years of age if the frontal lobes are in a different state of maturity?

To simplify, in public health either you scare people with the consequences of, for instance, smoking, or you talk about the positive aspect of not smoking. What I discovered is the younger the brain is, the more effective scaring is because you’re activating more primal areas of the brain that seek to resolve that dynamic tension of being threatened by the behavior, whereas as we mature, we tend to activate more rational engagement of the frontal lobe and we have almost an equal type of response between the positive framing and the negative framing.

Roger Dooley: Okay, so in this case, the emotional appeal works better on the younger brains.

Christophe Morin: It does. It does, and I have to say I do a lot of volunteering, and that message, or that guidance, is not always easy to implement because there’s a lot of concern around the political correctness of a message that is rather disturbing, if not shocking. Sadly, too many of the campaigns fail because they’re not informed by a theory. As best as people may be on the subject, it is, I think, reckless to create campaigns that are not at least supported by some sort of theoretical framework. The Persuasion Code, it sounds like a very complicated scientific book, but it really isn’t because, as you know, and this is a conversation you’ll probably have with Patrick, more than half of the book is about practical, tactical, easy-to-use steps to make sure the messages that you create and how you create them are basically following a theoretical framework based on neuroscience.

Roger Dooley: In the book, Christophe, you talked a lot about primal and rational brains. It’s really the two parts, and that ties into what we were just talking about with the different kinds of messaging. Do those map to Kahneman System 1 and System 2, or are they different?

Christophe Morin: To simplify, they do. This has been also an issue or a challenge with the neuromarketing industry until Kahneman successfully published Thinking, Fast and Slow and popularized this idea of two brain systems, System 1, which basically is the primal brain, is very a intuitive, very survival-centric part of the brain, lower brain areas, much older evolutionarily speaking; and System 2, that gives basically access to cognitive resources, rational thinking, and so on, which we simply call the rational brain.

That system and framework is quite brilliant, and what we wanted to do in the book is show that when you consider the role and the dynamic tension between System 1 and System 2 as it pertains to persuasion, you have to take into account that the dominance of System 1, or the dominance of the primal brain, is crucial to enhance and predict the effect of persuasive messages. So we go beyond Kahneman models by suggesting that a true effective message is a message that will achieve what we call a bottom-up effect from the primal brain first, meaning you cannot bypass the primal brain, to the rational brain second. Too many messages, and you see them every day, Roger, are under the illusion that we can go straight to the rational brain. They’re text-centric, they’re cognitive, heavy, and they fail to engage the primal brain.

Roger Dooley: Talk a little bit about the six stimuli, and I don’t think we’re going to be able to analyze them all in detail, but they seem like a pretty core concept in your book.

Christophe Morin: Yes. Once we identified and tested the dominance of the primal brain and the importance of the primal bottom-up effect, we investigated how messages could be created in order to activate or trigger the primal brain. We discovered that there were really only six ways by which you can activate the primal brain, and we don’t recommend that you pick and choose which one you like. We recommend that you use them all. That’s why we call that the language of the primal brain.

I’ll go through it very, very quickly. The first stimulus is to make sure your messages are intimately personal. Because that primal brain is survival-centric, no message is going to be relevant or important unless it speaks to something that matters to me. Because of the nature of our anxiety, it is quite obvious that we pay more attention to pain or threats than we tend to solutions or benefits. By being personal, it’s really all about engaging that primal vigilance that is at the core of the primal brain.

Contrastable speaks to the importance of accelerating buying decisions and choices because the primal brain has hardly any cognitive resources, and therefore, you can’t say to people that you have 15 reasons why they should buy your product. You have to contrast life without your product, and it should not be happy, with life with the product, and limit your number of what we call claims to three.

The third is making your message tangible. Tangible is all about bringing the evidence to the primal brain that can be assessed and believed right away. See, the primal brain doesn’t have really the concept of time and future, so you can’t use complicated pieces of evidence, like data or promises in the future. You have to ground your evidence on visuals or stories that people can intimately connect to just in a few seconds.

The fourth is all about making your message memorable. Memory is fragile, and the primal brain controls a lot of how our especially emotional memories function, and is really not on a mission to store a lot of information. But we’ll tend to memorize events that happen right at the beginning and right at the end, events that are highly emotional. There’s a code for making your message more memorable, and that’s not something you do by mistake; you have to prepare and input, if you will, into your message a code of memorability.

The last two are that, of course, visual is a dominant channel for the primal brain. We are basically visual decision making machines. Therefore, optimizing the visual impact is crucial. Finally, emotions represents almost the glue of your message. We know now through so many books and papers that emotions are central to the way we make decisions and central to the way we memorize anything. So when you put all this together, it is somewhat like a pilot checklist. What I have seen in my career, sadly, is too many campaigns where there is no checklist, number one. Number two, worse, there is no scientifical framework for creating effective messages.

Roger Dooley: Christophe, focus on contrastable for a minute, because I think that’s a term that is less familiar than some of the other ones to our listeners and to me too. Can you dig into that a little bit how you add contrastability, if you will, to an ad or ad campaign?

Christophe Morin: Yes. The primal brain is on a mission to make quick decisions, and only sharp contrasts, or distance between options, can accelerate that choice. What we mean by that is we don’t ideally make good decisions when we’re invited to consider a lot of choice, but we make better decisions and quicker decisions when we have limited choice. The choice that we are asking our customers to use in creating messages is, “Tell me what I’m not going to have if I miss the opportunity to buy your solution,” and that should be ugly and that should be sad and that should be potentially costly, and, “Tell me what my life is going to be if I buy this product,” and that should be happy, and that should be extremely exciting.

More importantly, spend the time which very few companies do, sharpening your claims to make sure that they truly represent a unique point of differentiation. In all the clients and work that we feature even on our website, you will instantly see that you can understand the contrast between a company that is identifying sharp claims and unique claims and a company that does not. It’s all about simplifying the decision. The primal brain understand go, no go; good, bad; expensive, cheap. Too often, messages are going beyond just a simple contrast into an array of options. We say companies spray and pray. Well, spraying and praying benefits or reasons on the brain doesn’t work.

Roger Dooley: What would an example be that shows that contrast?

Christophe Morin: I, of course, would invite people to go in the book and see all the visual stories we’ve got.

Roger Dooley: We’re audio only here, so you’ll just have to do your best, Christophe.

Christophe Morin: That’s right. You may know that Patrick and I have been speaking for a company called Vistage. Vistage is a wonderful solution for CEOs that want to get the peer review of a group of other CEOs. We speak for Vistage, and we help them craft a simple message to explain that Vistage is making leaders better, that they improve decisions, so they give them better decisions, and they deliver them better results. A message that simply says, “With Vistage you get better leadership, better decisions, better result,” is a message of contrast. You can be a good leader, but you could be a much better leader. Therefore, any messaging that has that built-in contrast or built-in gap is a message that is friendly to the primal brain.

I invite, again, lots of other examples are featured on our website. The simplicity of this technique may strikes you as being, “Duh,” yet if you go to website you will find that people talk about how they make certain things but they don’t go to the benefits and contrasting life before, life after. It’s a simple framework that you see in most infomercials, by the way. We tend to hate infomercials, but their ROI is 15 to 20 times higher than any other form of advertising. Why? Because they apply the contrast as well as I can imagine to make the offer easy to choose.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, they always show you before you use their magical product how horrible your life is. You have this stuff all over your rug and you can’t get it off, and then they bring out their magic cleaner and it goes away. Actually, I’ve used infomercials in the past as examples of other things. I mean, they use so many psychological techniques. They anchor you with really high prices. “Thousands of these were sold at $499. Act now. It’s only going to be $299, and we’re going to give you this free thing.” They’re like one continuous tutorial on how to use behavioral science to get people to buy stuff. And you know that they’re working, too. If you see an infomercial that’s been on for a period of weeks or you’ve seen it before, chances are they have tested that to death and it’s actually working every time it airs.

Christophe Morin: It is, and so is comparative advertising. There’s surprisingly few research on comparative advertising, but it’s extremely effective. Why is it effective? Because it is much easier for anybody to choose a product if you have the homework done for you of comparing why this product is superior to other products. We don’t want as consumers, deep inside our brain, we don’t want to work and kick in cognitive energy to figure out why we need to buy a product. That work has to be built in the contrast of your message.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think that one of the greatest ad campaigns of all time was Dell taking on Compaq, which is a total comparison ad. They drew such a sharp distinction between their lower prices and great technology and Compaq’s higher prices, that that really vaulted them into a leadership position. You know, I’ll read-

Christophe Morin: And you probably remember the campaign for Apple describing the nerdy PC buyer-

Roger Dooley: Oh, yeah.

Christophe Morin: … and the cool Apple buyer.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’ve heard about that a few times. Such a great ad because there you’re even going beyond contrasting your product. There, you’re getting into social identity of the buyer, which is even better. Do you want to be the cool kid, or do you want to be one of the nerds over there? Yeah, brilliant, brilliant campaign. We could keep going, Christophe, but I want to leave a little bit of unplowed ground for your co-author, Patrick. So let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Christophe Morinn, CEO of SalesBrain and co-author of the new book The Persuasion Code: How Neuromarketing Can Help You Persuade Anyone, Anywhere, Anytime. Christophe, how can people find you and your ideas online?

Christophe Morin: Very simple. You can visit our website at salesbrain.com. You can find me on LinkedIn, and I do enjoy growing this community of people that are not just interested in neuromarketing, but the entire field of persuasion science, which is growing and I think will provide the lift, I’m hoping, to an industry that is craving to make sure that we don’t waste as much time and energy making very ineffective messages.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. Stay tuned for our upcoming show next week with Patrick Renvoise, Christophe’s co-author. Christophe, thanks for being on the show. I’m glad you and Patrick finally decided to write your next book.

Christophe Morin: You’re very welcome, and thank you so much for inviting me, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at rogerdooley.com.