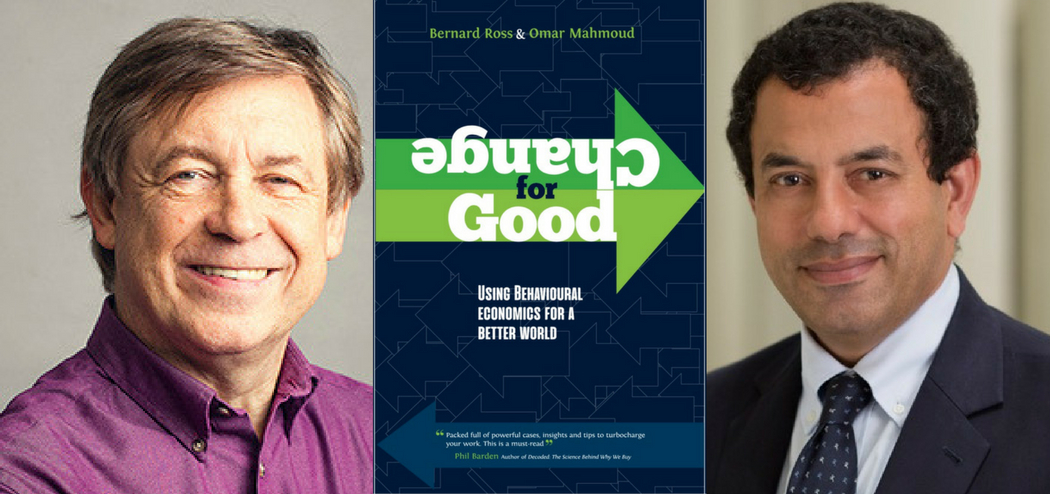

Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud are the authors of Change for Good: Using Behavioral Economics for a Better World, and they’re here to share how we can use behavioral science and neuromarketing to benefit society. Bernard’s areas of expertise include strategic thinking, change leadership, innovation, and organizational transformation, while Omar has over 30 years of experience in multinational corporations and international organizations.

Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud are the authors of Change for Good: Using Behavioral Economics for a Better World, and they’re here to share how we can use behavioral science and neuromarketing to benefit society. Bernard’s areas of expertise include strategic thinking, change leadership, innovation, and organizational transformation, while Omar has over 30 years of experience in multinational corporations and international organizations.

Currently working as the director of =mc—a management consultancy working worldwide for ethical organizations—and the Chief of Market Knowledge for UNICEF International Private Fundraising & Partnership division, respectively, Bernard and Omar join this episode to share their research and how we can apply it. Listen in to learn proven tactics for influencing behavior, the ethical concerns surrounding persuasive psychology, and important things to keep in mind when it comes to asking for donations.

Learn how we can use behavioral science and neuromarketing to benefit society with @bernardrossmc and @mgmtcentre, authors of CHANGE FOR GOOD. #nonprofit #socialpolicy #behavioralpsychology Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- A major issue in all of persuasion psychology and behavioral science.

- What research shows about emotional vs. rational messaging.

- How the nonprofit world is applying behavioral science to their efforts.

- What anchoring is and how it affects our perception.

- How framing can influence people’s decisions.

- A controversial approach to encouraging donations.

- How a simple change in messaging about coffee cups brought about a significant change in behavior.

- What charities can do to give people a sense of ownership regarding their donations.

- The very important principle to understand about the idea of agency.

- When it’s good to show progress for a fundraising effort.

- At what points during a project you’re likely to get the most donations.

Key Resources for Bernard Ross & Omar Mahmoud:

-

- Connect with Bernard Ross: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Connect with Omar Mahmoud: Website

- Amazon: Change for Good

- Change for Good Summary Handout

- Amazon: Predictably Irrational

- Amazon: Decoded

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. One of my favorite topics is how we can use tactics that fall under the behavioral science and neuromarketing umbrella in ways that benefit society in general.

Today, we have a couple of guests who are going to help us do that. I’ve done a few neuromarketing for non-profit speeches and webinars and I’ve even included a section of my Brainfluence book on that topic. But today’s guests have really done a deep dive into that. They are the authors of the new book “Change for Good: Using Behavioral Economics for a Better World”.

I will let them introduce themselves. Bernard and Omar, welcome to the show. Please let us know a little bit about yourselves.

Omar Mahmoud: My name is Omar Mahmoud. I am currently the Chief of Market Knowledge in UNICEF’s Private Fundraising and Partnership Division. My career was mostly in market research. I started with Procter & Gamble for 20 years, mostly in Geneva, with a three-year stay in the headquarters in Cincinnati, Ohio. I worked on many international brands like Ariel and Pampers and Pringles. My job involved primarily understanding of consumers and making sure that the products and the communication we developed was based on consumer insights.

I had a short stint in Novartis Consumer Health, working on OTC products and health and nutrition. About 11 years ago, I moved from the private sector to UNICEF, UNICEF’s special division called Private Fundraising and Partnerships, which generates funds to support these programs in the field from the private sector and the private sector is corporations, but more importantly, individuals.

So my job continues to be to try to understand the motivations and needs of our audience and make sure we satisfy them in appropriate ways.

Roger Dooley: Great and Bernard.

Bernard Ross: So I sadly have a slight more modest resume I think in that I’m younger than Omar, I should say, as well. My background has really always been in charities, not-for-profits in a variety of settings in the arts and culture and more laterally working with the big humanitarian organizations. So I met Omar through what we were doing on the strategy for UNICEF.

We’re in a room just now which is where Doctors Without Borders it’s called in the U.S., is planning to help deal with the terrible refugee challenge we have in the world. So my background is in that.

Some of the fun things I’ve done, so I’ve raised money to help save the last 700 great apes in Rwanda. They’re beautiful, beautiful creatures. We need to save them.

Recently, I’ve been helping raise money in Argentina where the largest dinosaur in the world was found, but the problem is, it’s a three-story dinosaur and they only have a two-story museum, so they` need to build another story and bizarre things.

Roger Dooley: That’s a good problem to have, I guess, you know?

Bernard Ross: It’s bizarre when some of your guests … is that the Eiffel Tower has been around for a long time. It was only meant to be up for 18 months for the great exhibition in the 19th Century. It now needs repairs and they launched a fundraising campaign to help restore the Eiffel Tower, which I was pleased to help with. So those are the kind of things I do for a living, really.

Roger Dooley: Well Bernard, you were an English major in college. How did you end up applying behavioral economics to nonprofits?

Bernard Ross: What a great question. You obviously do your homework, Roger. I think what’s interesting to me then is the power of language. Why do great books appeal to us? Why the opening sentence of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Marquez, the first time he ever … of when he heard the guns. There are some sentences, some phrases in great novels that move us deeply. Why is that? Why is a novel or even a piece of radio more powerful sometimes than a 3D immersive experience?

What’s going on in our brain to make that happen? So great question. I think behavioral economics answers for me some of the questions about why we’re moved or touched by things. Some things are the simplest things in a very straight-forward way.

Roger Dooley: Well, marketing involves a lot of emotion, so whether you’re telling a marketing story or perhaps telling a story in a novel, you still have to be aware of both, I guess. I found the book, “Change For Good,” to be really interesting. There are a lot of classic studies in there that many of our listeners are probably familiar with, as well as some experiments that you conducted yourself and you show how all of these can be applied to good causes.

I should tell our listeners that even if they are for-profit marketers that they’ll get a lot of value from the book. Of necessity, a lot of the examples are from the for-profit world and also, I think the more novel nonprofit ones still have good lessons in them. I’m curious, how aware is the nonprofit world of applying behavioral science to their efforts?

I know since my book, “Brainfluence,” came out and I’m not implying cause and effect, it seems like awareness has really grown exponentially in the business world. Companies like Walmart have behavioral science units and just about every conversion expert I know is familiar with the principles of influence psychology. How pervasive is that on the nonprofit side of things at this point?

Omar Mahmoud: I would say it’s again an excellent question. I think it’s growing exponentially, the awareness and knowledge of behavior economics and to a lesser extent, neuroscience, as well, in the nonprofit sector, but they’re still behind the commercial sector. In my experience in the private sector and maybe in particular because I worked on fast-moving consumer goods which for the most part are not very important for the consumer. This was in liquid household cleaner, laundry detergent.

How much time do you spend thinking about these categories and also, you realize over time that the technological or performance differences between the products are not huge. So you’re always searching for ways to make your product more relevant to the consumer and to show that your brand is more distinctive and there is something that the other brands do not do. So you make really a big effort to understand how people think, how they perceive information, how they process it and how they make decisions.

When I moved to the not-for-profit sector which is working for very good and noble causes, I found that the thinking was somewhat different. That since we are working on a very good cause, in our case for example saving children, child survival, early child development, child rights and so on, and then other organizations it might be about the environment or about animals, but it’s always for a good cause, you feel that you can just appeal to reason and facts.

Give the facts to your audience and give them logical arguments and they should support those causes. And I think this has changed over time. I think the nonprofit sector is catching up with the commercial sector, realizing that in theory, yes you give the facts and the data, but this is not how people make decisions. They are moved by their basic drives and instincts and emotions are extremely important.

I think the realization came slowly. There were some experiments that show for example that when you talk about real numbers, then you talk about the story of one child, not even two children, the one-child story has more of an impact. And as an interesting recent example, I don’t know if you’ve been following the situation of the children in Thailand who were stuck underground in a cave and the whole world is following this story, even though there are thousands of children who are dying every day from preventable causes.

But because it is a human story, dramatic one, and I saw, for example, in the English papers on the first page there is this story of the children who happen to be a football team and on the same page the news of the English football team that’s playing the semifinals today in the World Cup. So again, the timing is an important factor.

So I think there is growing realization that it’s not enough to use facts in appealing to your supporters, you need to understand what motivates them and appeal and make yourself relevant to their motivations.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. A few years ago in the U.S., there was a story that captured everybody’s attention. A baby fell down a deep well and they could not figure out how to get her out because it was a very narrow shaft and an adult couldn’t go down it. They were drilling shafts parallel to the well to try and reach her. It was a very captivating story, but it was not dissimilar to the trapped soccer players in the cave because it just captivated the media’s attention. Everybody was talking about it.

But again, you know it’s in this case one child was a lot more interesting to people than potentially thousands that are in danger from more mundane causes. So it’s not a new phenomenon. There is probably a message for nonprofits, right? Because the research I’ve seen shows that sometimes showing one child in need is a lot more effective than showing the magnitude of the problem or showing a bunch of children in need which is counter-intuitive.

But what’s the research on that show?

Bernard Ross: Well, I think there’s a lot research to show that, the identifiable victim effect, you know, you name one person and give them a name. That’s quite important, so it’s name this person. They are not using the language of hoards of refugees. It’s a very offensive language anyway. I have a great positive example, Roger, actually.

We recently did a project for a performing arts agency and they had hired a theater to put on an event to raise money. You know when you go into a theater, you either go down the left-hand side to the theater or the right-hand side down into the aisles. And we made images on one side of the theater which had numbers. Like last year, we helped 1000 children do this and 500 children do this and 50 schools do this. There were boards with those numbers.

On the other side, we told the story of six kids, six individual kids like little Jimmy. He had his first chance to hear the music of Shakespeare’s … You can see why I love this project with my background in English. So, the good news is the people who sat on the right-hand side of the theater and who had been exposed to those individual stories gave 50% more than the people who sat on the left-hand side of the theater because it’s a level experiment.

This is with five or six hundred people. This is not 20 students in Harvard who may or may not be typical. It’s a great example of the difference between essentially the same message, kids need access to literature and performing arts experience, but done in two streams and the six stories of the six individuals played much stronger than the big numbers of the impact they had.

Yeah, that’s a good … I think that’s a powerful …

Roger Dooley: And you know, I think that exhibits the whole emotional versus rational marketing because rationally, if I were a donor, I would like to know that gee, my donation is going to impact a lot of people that benefit lots of people as opposed … I mean nothing wrong with benefiting one, but the rational thing is to try and benefit as many people as possible. But at the same time, that messaging isn’t persuasive and it’s much more persuasive to talk about the one than the many. So that’s a great example.

You know, you guys did another experiment that I found interesting. Well first of all, I’m sure that most of our listeners are familiar with the concept of anchoring. Dan Ariely did some great experiments where he introduced random numbers to subjects and then asked them to put a value on different sort of objects, random objects that they might not know exactly what they cost.

And he showed that the values they placed were heavily influenced by the random number that they had been exposed to before that. This study, though, it might have had some of the difficulty you were talking about, where there’s a bunch of probably undergrad students at MIT or some institution.

You guys did an experiment at a marketing conference where presumably you’ve got a bunch of fairly sophisticated marketers, many of whom may well have read Dan Ariely’s book, “Predictably Irrational.” Tell us a little bit about that experiment.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah. That experiment was at the International Fund Raising Congress and as you mentioned, it’s high-level fund raisers who are in a way familiar with some of these tactics. First of all, we asked them to pick a number from a bag, told them these are numbers from 0-100. In reality, there were two numbers only. There was 10 and 65. Then we showed them a bottle of champagne and asked them how much was the highest amount of money they would be willing to pay for it.

We just recorded how much they were willing to pay and then we split the data by those who picked up the 10 versus the 65 and we found a big difference between the two. When people chose 65 as the number, the average amount they were willing to pay was 46 dollars. When they picked up the 10, it was only 19 dollars. So it’s a huge difference and the only difference is obviously, the same bottle of champagne.

They were influenced by a randomly-chosen number that had nothing to do with the champagne. To your point, even when you’re conscious of the tactics, you’re still influenced in many ways because it works on the subconscious. When you take, for example, the 10 it just sticks in your brain. You cannot get it out. And you move away from it. So people who chose the 10 did not say they were willing to pay 10. They actually were willing to pay 19.

But there was still influence in comparison to the others who chose the 65. And again, they didn’t go for 65 dollars, they went for 46. So they went down, but still there is a big gap between the two.

Bernard Ross: Yeah and I have an even more extraordinary example, Roger. It was even extraordinary to me. So some of your listeners might be familiar with what’s called face-to-face fund raising where you’re stalked in the street by generally a young person who says I’m collecting money on behalf of the XYZ cause. Would you be prepared to make a donation today?

It’s not always a popular form of fundraising, but it’s a very legitimate way to do it, especially in Europe. So I was in New York, was acting as one of the solicitors, stopping people in the streets saying, “Would you be interested in making a gift to this childcare organization?” Over half a day stopping people randomly in the street and perhaps trying to stop as many as 300 people, maybe only 50 or 60 people stopped.

I’d ask them to make a gift. They would make an average gift of 15 dollars. Those who did would make an average gift of 15 dollars. When I stood beside 23rd Street in New York and I’ve got a nice picture of this I can send you and I said to people, “Oh, thanks for stopping. Oh goodness, it’s” and I pointed to where it said the 23rd Street substation, you know it’s like a big poster, I said, “Oh goodness, it’s 23rd street.”

“Anyway, let me ask you …” I made exactly the same proposition having just mentioned the number of the street where we were, the average donation went up two dollars. So this is in one sense madness. In another sense, it’s the same as the champagne experiment.

Roger Dooley: Maybe you should have gone to 114th Street and try it again.

Bernard Ross: No. You got there too quickly. That’s interesting, just to say one last thing, because that raises … You know, in a conventional marketing sense, you know what, if you can get two dollars more for the product, why just not do it? Many charities are very nervous about using that technique because it raises ethical issues about changing behavior without changing minds and that’s a dimension that I think the book maybe …

That’s the dimension we’ve had to consider throughout the book, it’s one of the opening chapters, is to say because of the ethical issues that are important to charities, we can use these techniques, but should we? Are they proper? Do they represent philanthropy?

Roger Dooley: You know, I think that’s really a big issue in all of persuasion psychology and behavioral science. Obviously, it’s a little bit more so if you are simply trying to get people to buy your commercial product. Then it may seem a little bit more manipulative, although one hopes that indeed the product is going to deliver on the promises and that the person buying it will not regret their purchase.

Because the more that regret exists, then I think the greater the chance of claiming manipulation. That, gee, I wouldn’t have made this decision otherwise. I didn’t really want to make that decision, but I was manipulated into it. On the other hand, if they like the product and they bought it, then I think maybe everybody’s purpose is well-served by that.

But even on the nonprofit side, I guess there are issues right?

Omar Mahmoud: Yes and even more so because the nonprofit organization is supposed to hold the highest possible ethical standards. So as you mentioned before, it applies to all attempts when you’re trying to persuade or influence people, but I would say more so in the nonprofit sector.

I think … co-wrote a book specifically about ethics and behavior economics. One key point, of course, is the intent. As you mentioned, I like the way you put it about not regretting the decision that you made, so are you trying to help people make a decision for sustainability, for protecting the environment, for saving lives or to make them consume more sugar and become more obese or to smoke more? So I think that’s the key factor.

The second one is to make sure you’re not limiting the choices that people have. You might want to persuade them to take one option more than another, but still, the other options are there and one good example of that is the use of default option. You might change the default, although there is some more regulations on this happening now. But even when you specify the default, you’re still giving them the other option and the possibility to opt out.

Thirdly, of course the transparency. But to put this in perspective, also, when we talk, for example, much of behavior is about framing. In the traditional theories of economics we say what matters is the facts. Behavior economics says no, it’s not just the facts or the information, but how you frame that information. So what people need to realize is, also, there is no information without framing.

It’s like if you mention the word framing coming from framing a picture or a painting, you may be able to put the painting or picture on the wall without any physical frame, the wall becomes the frame. So no matter how you’re presenting the information, there is a frame. So we’re trying to frame it in a way that will help us support a good cause.

Roger Dooley: I can see occasionally it being controversial. It’s hard to argue with, say, getting people to sign up to be organ donors. That’s benefiting society and once you’re deceased, you really don’t need those organs so that seems like a more or less unmitigated good. On the other hand, you talk about, say, nudging people to include charitable bequests in a will so that when they die some of their money will go to charity.

I could see that being a little more controversial, where if maybe an heir is counting on some money from grandma’s will and instead, grandma gets nudged into giving half her money to or maybe giving all of it to charity, then that could really be seen as a negative nudge.

Bernard Ross: For sure, Roger. I mean I’m gonna back away from that one because you’ve touched what is a very controversial topic, certainly in the U.K. Let me give you a simple example. Conventionally, I don’t go to the theater enough in the U.S., but if I go to the theater in the U.K., I might buy a very nice ticket because I go with my wife, we spend 80 pounds on the tickets and at the end of the transaction, the theater will say, “Bernard, we’d love you to support theater. Would you add 5 pounds to the price of your ticket as a donation?”

And it will say 5 pounds, 10 pounds, 15 pounds, blah, blah, blah. I choose to do that on my own, but let’s face it. It’s a very modest addition. A glass of wine costs more than 5 pounds. A program costs more than 5 pounds. I recently went to the Metropolitan Opera in New York and bought tickets, as you can imagine are several hundred dollars. I think I spent six hundred dollars on tickets.

The Metropolitan Opera said to me, “Dear Bernard: Thank you for doing that. Would you like to add …” and it was something like 60 dollars to the price. I thought, goodness, that’s a lot as a donation, but then I realized and I’m wondering if I’ve done the mathematics correctly this time, that it was 20 percent of the value of the tickets that I had bought.

Of course, as I know as a European visiting to New York, if you try and leave a New York Restaurant without leaving a 20 percent tip, the waiter will call you back and explain you’ve made a mistake. So I think that was a very cute little nudge about saying, (a) “Please make a donation,” (b) “Please make a donation in line with the tickets you seem able to buy,” and (c) making a normalized donation and that was the 20 percent I was used to paying in the restaurant.

So I thought on the one hand, I thought I’ve paid a lot of the tickets, but they’re asking for a lot more. And then I thought it was cleverly done.

Roger Dooley: Right. I could see several ways of improving that, though, because I think somebody who just paid that sum of money for opera tickets might be reluctant and they’re already feeling pain from that purchase. They might be reluctant to add a big donation on that, but perhaps sort of anchoring a larger donation and saying well, would you at least do 20 dollars or something would probably get a pretty high compliance rate, maybe.

Or I think if they frame that in a way as you suggested, where they really talk about comparing it to some other life situation where that would be a reasonable donation or a tip, then that might work. What do you think?

Bernard Ross: I think the thing I would have suggested to them … I wasn’t involved in that at all, but what I’ve done with theater companies here is say, “You know, for 60 dollars we could get a whole school of kids to come to this show and share your love of opera.”

If you’re somebody who loves opera or I’m a big opera and performing arts fan, to share that love that you got as a child from someone else, that’s … You know, I’m happy to chip out for that.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Bernard Ross: … there’s still work for us to do in the field which is as long as there’s work for you and for us, that’s good.

Roger Dooley: Right. You know, I just did a blog post a few weeks ago about something I observed in London at the Tower of London, where there, they take a different approach. It’s kind of similar to the nudges that you’re talking about, but what they do is they have a posted price and that price includes a voluntary donation.

So they have different classes of admission depending on what you want to see and so on and how old you are, but perhaps admission is 20 pounds and it says this includes a voluntary donation of two pounds and some odd change and they note in the fine print what the actual price is and it’s some weird little odd number of 17 pounds and 65 pence or something.

So that most of the people … I talked to one of the ticket sellers and said, “You know, what percentage of people ask for the lower ticket price with no donation?” And she said, “Probably one out of five does.” And that’s not necessarily representative. I didn’t quiz them or I didn’t talk to the people in the office who actually know what those statistics are.

But they were getting perhaps an 80 percent donation compliance rate by making the customers or the visitor have to opt out rather than opting in to the donation. I think it’s a great strategy. I’m sure it increases the number of people who are contributing, but certainly some of the people who reacted to the blog post said, “Gee, that’s kind of sketchy. That’s a little bit unethical because some people aren’t even gonna notice that they’re making a supposedly voluntary donation.”

Bernard Ross: Yeah, you know Roger, you’re hitting all the … These are all the issues we have to try and deal with. So you’re absolutely right. That’s actually a very controversial scheme. I know I saw it in your blog and there was an opera company who do a similar thing. But it’s just interesting. I absolutely see why the pure marketer in you likes that and why the pure marketer, I think, in Omar likes that, but it’s caused a lot of controversy.

That’s good. I think in all these circumstances, we’re seeing people … You know what? It is a thing that works. Please make that an ethical choice to use it or not, but it’s not our ethics, it’s your ethics. It’s the ethics of the agency.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah. We came across an interesting example recently from the U.K., where they were trying to encourage people to use their own cups as opposed to using disposable coffee cups. Originally, the scenario was you bought a cup of coffee which is disposable for one pound, but if you brought your own cup or mug, you paid only 75p. The response was not very high.

And so to summarize this one, it was one pound with the disposable cup and 75p and your own cup. So they changed it to be the coffee is for 75p when you bring your own mug, but if you want to have a disposable cup, then you pay 25p penalty. Then they found a huge transformation.

Roger Dooley: It sounds like they have some loss aversion going on there.

Bernard Ross: Yeah, absolutely.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah. Yeah. Rationally speaking, it’s exactly the same scenario.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well there’s a great lesson there, too, I think even for commercial marketers who are perhaps trying to steer people in a certain way. The way they price it may seem identical, but it can definitely change behavior.

Bernard Ross: Yeah.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah.

Bernard Ross: There’s some nice things, too. I mean we’ve talked a lot about price. I came across a beautiful example. The other day I was doing a seminar in Vienna and a woman came up to me and said, “Can I show you this?” We’d been talking about nudging and the speed of response. She showed me her phone. She had three messages on WhatsApp from the Austrian blood transfusion service.

The first one said, “Dear Olga,” I forget what her name was, “Don’t forget your blood donation is tomorrow at 9 o’clock. Looking forward to seeing you, Hans. Blah, blah, blah.” So she went and she made her donation. After she left, within half an hour she had a text message saying, “Dear Olga, just to say to you thanks so much for coming today. We hope to see you again in three months,” this fictional person, Hans.

Then a week later, “Dear Olga, I thought you might want to know that today we used your blood to save a patient. Thank you so much.” I thought that was beautiful.

Roger Dooley: That’s brilliant. Was it real do you think?

Bernard Ross: Was it real?

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I mean actually did they use her blood or is this a part of their drip sequence?

Bernard Ross: I find Austria is a pretty straight place. I think that was true. I think they would struggle to do that and yeah, no, no, so I … But I just thought how nice. Now there’s a woman who’s going to be committed to giving blood.

Roger Dooley: Well for sure. Yeah. That’s brilliant. I think all kinds of charities can use that just to say to a donor, “Hey, you know that donation you gave us a month ago? Here’s something we did with it.” Even if it’s something very small or you were just a part of it because your donation didn’t pay for the whole thing, but that sort of sense of ownership in the result I think is really powerful.

Bernard Ross: Yeah. Well another beautiful example if your listeners want to come out, Oxfam in Great Britain had some criticism recently for some of the #MeToo scandals, but they’ve got a beautiful thing on their web site where if you make a donation, you are sent a link and you can follow … It doesn’t exactly say your money has now been turned into foodstuffs and the foodstuffs are leaving London and they landed in Addis Ababa and now they’re on a truck.

But it kind of gives you … You know like Amazon sends you a thing saying it’s in the sorting center and now it’s being …. It’s at that level of granularity. They do nice things like say the well, the pumping well for the water is now in transit. It’s just very nice that you can go in and kind of see roughly what you’re money has done and how the donation is done.

So I think that’s a place where the nonprofit world has actually picked up and really doing some good stuff by saying here’s where your money is, here’s what it’s done.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah. And sometimes, also, you can combine different tactics. You show how the money has been used by that person and giving the person a name. I think we split all the tactics individually for the sake of clarity, but their power multiplies when we combine them. So in the example, we talked about the coffee. As you mentioned, this loss aversion is also changing the default. It’s a different kind of anchoring. It becomes more powerful when you combine tactics.

Roger Dooley: You know, even before a donation I think there’s things that charities can do. I think there’s one charity, I forget the name of it, that I’ve seen literature for and they will tell you, “Your donation of 100 dollars will buy a cow for a village in Africa.” They’ll make it rather specific sounding and, “Oh, you can’t afford that much? Well, the smaller donation will buy a goat or a larger one will buy a well,” and so on.

And if you read the fine print, it basically says, “We aren’t actually going to buy a cow with your money. These are representative values” or something. But I think that makes it tangible. Because otherwise, I know that sometimes donors, have a tendency to feel, especially if they’re smaller donors, well yeah, I’m gonna give my small amount here and then there’s going to be somebody else who donates a million dollars. Why should I even bother?

Where at least, this turns even a modest donation and it goes all the way down to a chicken that will supply one family with eggs that even very, very small donations are having an impact.

Bernard Ross: I think another very important principle about the idea of agency, the idea that you can make a difference in your modest way and there’s no point in waiting for the government to do it or even the blessed Mr. Gates to do it with his many millions. Take action now and do something. But I think you’re right. Interesting, I think the goat is the most popular default. If that really happened, I’m sure there’d be African countries calling up, saying, “Please stop sending the goats. We have enough goats. Please send something else.”

It’s interesting. We like to, although we read the small print and say well of course, I know they don’t put a goat in a box and send a goat, but I like to feel that’s what I did. It gives me a sense of agency and a sense of concreteness.

Omar Mahmoud: I think people are familiar probably with the work of … and the work of …. One of the other books that influences very much was “Decoded,” written by Phil Barden. And it’s really I think the best book on the application of behavior economics to marketing.

We’ve been working with Phil Barden and his company, Decoded, and one of the things we learned is the importance of making your communication and what you are going to do at an organization with the money, make it tangible, you make it immediate and you make it certain. We call it TIC for short.

So when we talk about the cow or something very concrete, this makes the use of the donation very tangible. Also, the timing is important. If there’s a big gap between the time of the donation and the impact it has, there is less feeling that this is actually the impact of what the donor has done and then the certain is not something that might or might not happen in the future.

So that’s an acronym I try to remember all the time. Here’s this message, TIC: Tangible, immediate and certain.

Bernard Ross: I think your book has some great insights in it and Phil Barden’s is the other book I would have on my shelf, also.

Roger Dooley: Great. Let me ask you about one last topic. I’m curious about progress. You know, we’ve all seen these fundraising charts where there’s a big thermometer, something that’s gradually filling up as a campaign starts off with the beginning of it’s goal and gets partially there and then gets near the top and so on.

You’ve got some interesting findings about when it’s good for an organization to show progress and maybe when it should be expressed in some different way. Why don’t you briefly talk about that.

Omar Mahmoud: Yeah. I think if we look at from an evolution psychology point of view, most of our history, our communication was in the form of stories. And the story ultimately has a beginning, middle and an end. We’re used to this form of communication more than we are used to reading data and statistics. And psychologists call this desire of ours to see things progressing and getting to completion the need for closure.

We don’t like to see things open and even today when we watch a movie, if the ending is not very clear, we want to discuss it with our friends. What really happened? What do you think happened? That’s why people who are now following the soap opera or something, they cannot stop after they say I’ll watch one episode and then they say I want to know what happened next.

So this is a very basic desire in ourselves and the progress when you feel that something will be completed, the project will be completed, a service will be delivered, an epidemic will be eliminated, that gives us more of a desire to be part of that, to reach that goal. We are a goal-seeking species. But of course there’s some dynamics involved in that. It’s not a linear relationship.

So at the beginning of a project, if you achieve, for example 10 or 20 percent of the project, you should refer to the smaller number all the time. So we’ve already done 20 percent and overcame the initial inertia. You don’t say we still have 80 percent to go. When you reach 80 percent, you talk about the 80 percent and there’s only 20 percent to go and then we know that there will be an acceleration in the donation or the help because we all like to see something come to an end and complete.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well I guess it’s fairly typical in fundraising efforts that I have personally observed to go out for big donations first. Before you even launch the campaign, they go out and try and raise a significant portion of the funds from big donors. Is that sort of an endowed progress effect?

I know we’ve seen the coffee experiments where you give somebody a coffee punch card where you get a free one when it’s full, if you give them a card with either 10 empty spots or a card with 12 spots of which two are already checked, they will consume more coffee with the one that looks like they’ve already made progress. Is that the same psychology there?

Bernard Ross: I think there’s some similarities. I don’t know anyone who’s doing the coffee experiment or the car wash experiment the same way. I think Omar and I are trying to think about how you might do that. It’s sadly the case and there’s some data, I think you’re probably referring to the book, but when you’re seeking donations for a project, you’re more likely to get acceleration at the start and at the end and not in the middle. So projects can get kind of stuck in the middle.

Yeah. That idea of like there are certain points and of course then how you frame your project becomes important.

Roger Dooley: Right. So you don’t wanna be in the middle. You want to be starting phase two, for example, right?

Bernard Ross: Yeah and Roger, you know, you have the chance. You can kick off these two. You can be a leader. You can start other people involved. Roger, with your gift, you can make this happen. You can get completion. Those seem to be the two most powerful points. So presenting your proposition in a way all the time that suggests that you’re in one of those two positions and not getting stuck in the middle.

Omar Mahmoud: There’s also one point where subtle difference on the example of the card with the 10 and the 12 spots, that’s purely about the progress effect. But in some other cases where you’re telling people publicly how much of the projects have been completed, there’s also another factor which is the social reference factor. It tells you that you’re not the only one. There are other people that have donated and they cannot all be wrong.

I think once you really get interested in behavior economics, you start seeing it everywhere. If you see, for example, a street musician and they’re playing music and they have their hat and there’s some coins in it. You’re more encouraged to donate than if the hat is empty because you feel others have already donated.

I think that’s another dimension that despite being common knowledge to a large extent, but the social reference and the social pressure is a very important factor that I think is under-exploited, whether it be commercial sector or not-for-profit. We think of thinking as an individual exercise and process, but actually, it’s very much social.

Roger Dooley: Great. That’s a pretty good place to wrap up, I think guys. We could go on for hours. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud, authors of “Change For Good: Using Behavioral Economics For A Better World.”

How can folks find you guys online?

Bernard Ross: I think you can find us through our web site at www management center, spelled the U.K. way, that’s management centre, c-e-n-t-r-e, dot com dot UK. And I think you can contact Omar through of course the ever popular Amazon is a great place to buy the book.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well we will link to all those places, including the book and any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there, too.

Gentlemen, thanks for being on the show.

Bernard Ross: Roger, thanks so much and thank you, also, for the inspiration. I think as you read the book you also thought, “Goodness, I recognize those ideas.” Thanks for the inspiration you’ve provided us with. It’s been great.

Omar Mahmoud: Thank you very much, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.