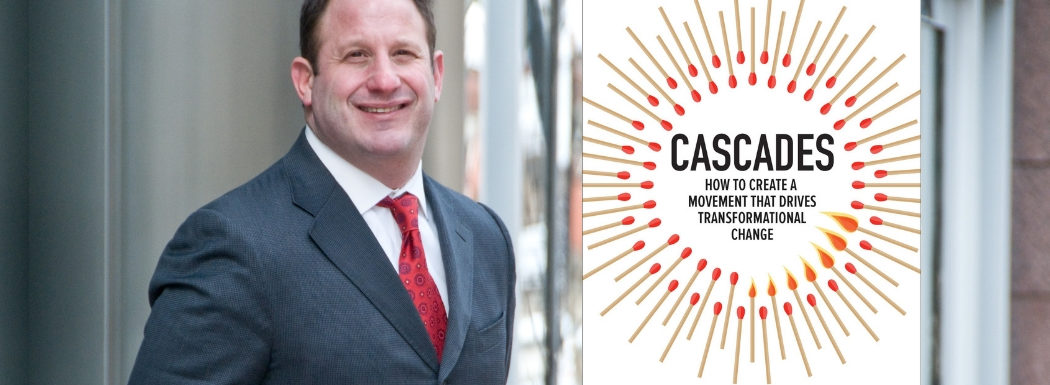

Greg Satell is a popular author, speaker, and trusted advisor. The author of Cascades: How to Create a Movement that Drives Transformational Change and Mapping Innovation (which was selected as one of the best business books of 2017 by 800-CEO-Read), Greg has been published in Harvard Business Review and Ink, and has been recognized as a thought leader by many others.

Greg Satell is a popular author, speaker, and trusted advisor. The author of Cascades: How to Create a Movement that Drives Transformational Change and Mapping Innovation (which was selected as one of the best business books of 2017 by 800-CEO-Read), Greg has been published in Harvard Business Review and Ink, and has been recognized as a thought leader by many others.

In this episode, Greg breaks down what it really takes to grow awareness and coordinate movement for change. Listen in to learn the keys to viral marketing, advice for increasing awareness, and how to get people to take part in a cause.

Does your organization need to change? In a BIG way? Greg Satell, aka @DigitalTonto and author of CASCADES, shows you how. #changemanagement #innovation #change Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The three principles that coordinate movement for change.

- A simple concept many movements fail to internalize.

- What it takes to create viral marketing.

- Advice for building awareness.

- What marketers need to understand about how to make something “sticky.”

- The accident that led to Einstein’s notoriety.

- How to get people to volunteer to help a cause.

- The first step toward commitment.

- Why it can be a challenge to survive victory.

Key Resources for Greg Satell:

-

- Connect with Greg Satell: Website | Blog | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Amazon: Cascades

- Kindle: Cascades

- The Science of Success with Albert-Laszlo Barabasi

- Cialdini’s 6 Principles of Influence

- AnnaLee Saxenian

- Amazon: Regional Advantage

- Amazon: The New Argonauts

- Niels Bohr

- Srđa Popović

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week is Greg Satell. Greg has a fascinating background. His writing can be found in Harvard Business Review and Ink. He’s been recognized as a thought leader by many others, but before that, Greg spent 15 years living and working in Eastern Europe, where, among other things, he managed a leading news organization during Ukraine’s Orange Revolution.

In fact, there’s something else unique about Greg. He is the first guest that I can introduce with the phrase, “Fellow McGraw-Hill author.” My book, Friction is due out about a month from now from the time you’re listening to this, and Greg’s new book, Cascades: How to Create a Movement that Drives Transformational Change is just out now. We both share a publisher, McGraw-Hill Education, and even the same editor. Greg’s previous book, Mapping Innovation, was selected as one of the best business books of 2017 by 800-CEO-Read. Greg, welcome to the show.

Greg Satell: Thanks for having me, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Greg, first, I have to commend you on getting a second book out so quickly after the last one. That is way more efficient than I’ve been. It’s been just a few more years for me.

Greg Satell: Well, actually, I started this book before Mapping Innovation. I’ve been working on it since 2004, so about 15 years.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Well, I take back what I said then. No. It is great to have two books come out in fairly short order like that. That’s really good.

Greg Satell: To tell you what a glutton for punishment is, I’m already working on the next one, so-

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s good. That’s good. These days, it seems like an author has to be torn between promoting the current book and making sure that that’s successful and actually working on the task of writing it. I don’t think that Hemingway had to worry about that. I think that he could write and turn it over to his publisher, and they pretty much did the rest. These days, as we both know, authors have to be their own sales machines too.

Greg Satell: Well, writing gives you license to explore. There’s always new things I want to explore, and that’s why I write books.

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s great. Yeah. I’m curious. Throughout the book, refer to your experience in Eastern Europe, and I’m curious. Can you give us the capsule version of that story? It’s an atypical background for most of the guests we have on the show. What’s your story there, and how did it end up informing, at least in part, Cascades?

Greg Satell: Well, I spent altogether 15 years in Eastern Europe, including Poland, Ukraine, Moscow and Istanbul, but the root of the book really started in Ukraine. In 2004, I was running a major news organization in the middle of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution. That had a great impact on me. What I noticed at the time was, and what really amazed me was, that thousands upon thousands of people who would ordinarily be doing thousands of different things would stop what they were doing and begin doing the same thing altogether in complete unison in ways large and small.

Running a significant business at the time, I thought to myself, “I’d really like to do that.” There’s all these different customers buying all these different things. I’d like them to buy what I want to sell them. I have all these employees with all their own ideas. I want them to embrace the initiative that I want them to embrace, and similar things with our investors and our advertisers, so I really wanted to figure out how that worked.

During the Orange Revolution, there seem to be this strange force driving everything forward and coordinating everything. Then, a few years later, I was out in Silicon Valley, and everybody was talking about social networks, and we had a very, very sizable digital operation, so I said, “I should really learn how this works.” I started reading up on network size, and what I found was an absolutely clear mathematical framework for almost everything that happened during the Orange Revolution.

That’s what really hooked me. I’ve been spending, and the, ever since, to figure out how that process works, how you coordinate action among a lot of different people and get everybody aligned in the same direction. What I found was, that was, that really fascinated me was, that the same principles hold true, whether it is in a social movement, a political movement, in a marketing context or in an organizational context, things like the turnaround, the turnarounds of companies like IDM and Alcoa, or the campaign to implement quality practices in the healthcare industry.

Just everywhere I looked, you see, saw the same principles at work. In the book, I show how you can use those principles to create your own movement for change, whether that’s in your organization, in your industry, in your community or throughout society as a whole.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, so what are some of those key principles? I mean, it seems very different to do something inside a company, a small company, a large company, or in a much more disorganized population inside a country, it’s … What are the unifying factors that you found?

Greg Satell: Well, first, it’s this concept of a cascade, which is something that scientists have known about for hundreds of years. That, in nature, there is this strange ability to coordinate action within a network, whether that’s pacemaker cells in the heart or certain species of fireflies that can coordinate their blinking and turn entire forests into a Christmas tree or like a wave at a stadium. It was only in the late 90s when two teams of scientists really figured out how that process works.

As it turns out, there are basically three principles, small groups that become loosely connected and yet united by a shared purpose. That’s what drives this viral activity. Another interesting aspect of it is, that it’s really driven by connections. If you remember some years back, there was this craze about Wildcats that just seem to explode onto everybody’s consciousness, but there was this … Where the Wildcats really came from was the online community 4Chan, and it had been incubating for I think a year or 18 months before anybody else was even aware of it.

I think when you talk about things like viral marketing, everybody thinks that you can spark something instantly. It’s happened in the past, but only if you luck into a network that already exist. If you want to market something virally, what you really need to do is build that network beforehand in order to make the communication flow through. Some other interesting aspects are this idea of a keystone change. Often there, you need an initial thing that unites stakeholders and paves the way for a bigger vision, and lots of great examples of that in the book.

Finally, the idea that a movement needs to be built on values. If you think of something like Occupy, where there was a cascade, but it spun out of control and then died very quickly compared to something like the Indian Independence Movement or the Civil Rights Movement, where they really prepared for years and built the values into the network. That’s how they were able to survive victory even against enormous odds.

Roger Dooley: Just a week or so ago, and now I’m not sure when these episodes will be appearing exactly, but I spoke to Albert-Laszlo Barabasi about his book, The Formula, that also talked about networks and how they affect success of anything, so I think it’s … There’s a lot of evidence for what you’re talking about, Greg.

Greg Satell: Yeah. Absolutely. There is an absolutely fantastic example in that book. I mean, Barabasi was one, leading one of the teams that came up with the big breakthroughs in the late 90s. The other, as you know, was Steve Strogatz and Duncan Watts. What I loved, the incident I loved in Barabasi’s book was the story of Albert Einstein and how he, initially, he wasn’t thought of very much. I mean, he wasn’t that well-known, and the coverage of him was largely negative, until he arrived in America in 1921.

The newspapers sent some reporters out to see this physicist of some importance. When they got there, they saw that there was 20,000 people to meet the ship, and they were amazed that Albert Einstein was so popular. The story made it into, onto the front pages of all the major newspapers the next year. Well, actually, the people weren’t there to see Einstein. It was all a big mistake.

They were there to see Chaim Weizmann, the famous Zionist activist who Albert Einstein was traveling with. Because of that accident, Einstein gained some notoriety, and it ended up being a great case study in Barabasi’s concept of the-rich-get-richer phenomenon is the common theme, but he calls it-

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I forget his term.

Greg Satell: … preferential attachment.

Roger Dooley: Yeah.

Greg Satell: Right.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, and of course, also, it’s something, a concept that’s really familiar to our listeners is, that what you have there is an example of social proof, one of Cialdini’s principles of influence, where you see 20,000 people greeting somebody, then you just assume that person must be important and famous. In this case, it may have been false social proof, but it shows how effective it is.

Greg Satell: Yeah. I think both concepts are at work there, but one of the things I think that’s fascinating about Barabasi’s work is that small, initial difference, and then he went and tested the concept on sites like, or he covered research that tested on sites like crowd finance sites, crowdfunding sites, change.org. Even just a very minor initial boost ends up making an amazing difference in final outcomes.

In the case of Einstein, back then, there was a lot of famous physicists. Niels Bohr, for example, was at least as prominent, if not, more than Einstein. Because people had that image of that strange, likable professor with the crazy hair who had gotten that initial coverage, whenever physics, whenever a physics discovery was announced, they always referred back to Einstein, and that’s what drove his fame.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. It’s great. I think that for the marketers in our audience too, there is a lesson there, that if you can achieve some of that early recognition, when you’re introducing a brand or a product, or you’re trying to get noticed that, that could be really a tipping point. You might not realize it at the time, but if you can get that initial boost at the outset, it may well help you for years to come.

Greg Satell: Yeah. I think that’s definitely a great lesson for marketers. Another one is, that I think is very interesting and very related to Barabasi’s work is, the fact that the reason Einstein got that initial boost was, because he, of his involvement in not just one, but two significant networks. He had built his reputation, of course, in the community of science, but he got that initial boost, because he was active in the community of Zionist activism and politics.

He is almost as famous as much for that. I think in marketing, we often get too focused on hyper targeting and this particular target group, when, actually, you can gain more awareness if you’re not all over the place, but you’re involved with different communities.

Roger Dooley: Right. Yeah. That makes a huge amount of sense, but I do think that we are often really targeted today. It’s like we want to hone in on the exact influencers and so on, but casting a little wider net isn’t a bad idea. Greg, one person we have in common is a professor from Berkeley, AnnaLee Saxenian, and I wrote about her work in Friction. She compared Silicon Valley to Boston’s Route 128 in the formative years back in the chip days and how Silicon Valley ended up generating over time far more tech success than Route 128 did.

It became Silicon Valley, and Boston didn’t. I use it as an example of friction, where if not, as her research showed, the Boston area was relatively high friction, poised to do business for entrepreneurs and even individual employees. It was dominated by these big, vertically and integrated companies. It was not that easy to start a company. There was no network of supplier companies that you could easily deal with, because they were all, all the businesses, they were vertically integrated. If you tried to break away and start your own business, you’d likely be sued for noncompete or some other intellectual property issue.

Although, there’s much more freewheeling, easier to do business in Silicon Valley, but I’m curious. How does AnnaLee Saxenian’s work relate to yours?

Greg Satell: Yeah. Well, I also spent quite a bit of time talking about that contrast between Route 128 and Silicon Valley. I think this is a great intersection of your work and my work, because where you see friction, I see a closed network. You mentioned that Boston was vertically integrated, and that did create friction, and as well as in Boston, if you left digital equipment or data general, you became an outcast, where in Silicon Valley, if you left, you became an important contact on the outside. You became a potential customer or a supplier.

Because of those open networks, they were able to let information in and adapt to changes in the marketplace, where that closed networks of Boston made it very, very rigid and made it very hard for them to adapt and innovate outside of microcomputers or, excuse me, minicomputers. I think, in many ways, that’s, it’s interesting that you see it in terms of friction, and I see it in terms of networks. Obviously, both are true. Both those things are absolutely true, but they’re two different sides of a very similar coin I think.

Another, it just … Another aspect that is not in any of Anna’s books, but I had during a discussion with her, we were talking about the relation between both her books. She wrote Regional Advantage about Silicon Valley and Route 128 in Boston. Then, she came out with another book called The New Argonauts, about all the other tech centers around the world that have risen up since then, places like Taipei and Tel Aviv and Bangalore.

What was so interesting, she told me, she said, “After Silicon Valley, none of these places grew up, appeared de novo.” She said, “Silicon Valley was a strange confluence of forces.” She said, “Of course, in Silicon Valley, the places like Cal Berkeley and Stanford were open the young companies, because there were no major companies out there,” where Harvard and MIT were not so, were old establishment universities. There was a bunch of strange coincidences that all combined to make Silicon Valley.

When you look at any other tech center around the world, they all rose in connection to Silicon Valley. For instance, someone would work, people would work for 10 years in Silicon Valley and then go back home to Tel Aviv or Thailand or Taipei or whatever it was, and they would start a business either buying or selling things from Silicon Valley. Eventually, they began to specialize and become centers of excellence for particular technologies.

I think for marketing, that’s important as well. When you’re talking about how to make something sticky, it’s being open and building those connections and maintaining those connections and widening and deepening those connections that really creates this viral behavior that actually sticks.

Roger Dooley: Really, these other seemingly independent centers are actually just part of a bigger network. They are nodes, initially, maybe small extensions of Silicon Valley that ended up becoming important nodes themselves.

Greg Satell: Absolutely. The interesting thing is, their rise reinforces the centrality of Silicon Valley if you think about the network dynamics of it. It’s so funny. When you see the failed tech hubs, places like Skolkovo, outside of Moscow, where they want to build the new Silicon Valley, so they say, and they copy all of the outward structures of Silicon Valley, things like technology parks and incubators and accelerators and venture capital, but they forget the one element you need to make the next Silicon Valley, which is Silicon Valley.

They never build those connections. That’s why they fail. I think when you’re thinking about how to build a market and how to create a community around a product, you always want to connect with something that’s already there and build out on those connections, rather than trying to create something, as Anna said, de novo.

Roger Dooley: Jumping back to your networks, and, also, you talked about platforms in the book, I mean, to me, you look at them in one sense, but from my standpoint, they are friction reducers. Networks tend to reduce friction and platforms do.

I’m trying to imagine shopping for out-of-print books before eBay or Amazon existed, that when there was no platform for that, you simply had to try and use, call up bookstores or use maybe some antiquated paper-based network that circulated once every month or two or something like that, compared to, obviously, the instantaneous digital platforms that exist today. That, I think that these really operate both in your world and my world, because they are friction reducers, but they are also forms of networks.

Greg Satell: I think that’s absolutely true. One of the key sources in my book is a man named Srđa Popović, who helped lead the revolution that overthrew Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia, and has since trained activists all across the world, I think 50 or so countries. Anywhere you’ve seen one of these massive political uprisings, whether it’s Egypt or Zimbabwe or Burma, he’s trained, he and his organization have trained activists there. He told me something very much along the lines of what you said.

He said, when you’re designing tactics, you want to choose something that is cheap to do, not resource intensive and doesn’t ask a lot of people. In your words, you want to choose tactics that are as frictionless as possible. It’s amazing, such a simple concept that so many movements failed to internalize. They are looking for commitment. They want people to show how committed they are. They wanted them to brave the elements.

I mean, if you think about something like Occupy, to go and spend your life occupying a park, that’s a very, very high fiction thing. I mean, you can’t go to work. You can’t take care of your family. You can’t really see friends. Those actions generally fail, where, there’s a great example from the National Health Service in Britain, where they created something called a change deck. The whole idea is, that one day out of the year, each NHS employee is supposed to pledge to do one thing to better the lives of patients.

For instance, one particular ward that works with seniors wore continents pads for a day to better understand the plight of their patients. In the first year, I think they had 189,000 participants, and that rose to 800,000 participants in the second year. Very much in terms of your book and your ideas, I think that’s very, very true also when you’re trying to drive change. You need to make that as frictionless as possible.

Roger Dooley: Whenever you make something easier, you’ll get people to do more of it. The harder something is, the less you’ll get of it. There was a classic psychology experiment that would ask people to either perform a very simple task, like spend one time, two hours working with underprivileged students, or other condition was, spend Saturday mornings for 10 weeks working for several hours with those students, and the purpose of the experiment was to illustrate that the way you ask things got different results.

I think to what you’re saying, Greg, the difficult condition got no volunteers at all. Nobody volunteered to do that, where the easy condition got quite a few volunteers. The purpose of the experiment was to show that if you ask people to, first, to turn down the difficult one, and then ask them for the easy one, you got a higher compliance rate on the easy one. It’s true. People don’t recognize, that you have to be very measured in your requests if you’re trying to get people to do stuff.

You see that all the time in nonprofits, where they ask, “Hey, we need volunteers for this.” Then, they outline a program of effort that does, really going to take high level of commitment. It’s good if you can get a few of those. You’re not going to get the massive volunteers that you need to really get stuff done.

Greg Satell: Right. I think the cognitive dissonance there is, that all too often, people want to see commitment. They value commitment. They’re looking for people of the most pure of heart, where, and what they fail to recognize is, before you can have commitment, you first must have participation, right? You want to recruit as many people in as you can, and then that gives them the opportunity to become committed.

There were two academics, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, and they did a study of hundreds of uprisings over the past hundred years or so. What they found was, a couple of things. First, that nonviolent revolts were much, much more effective than violent revolutions.

What was interesting and very much in tune with your ideas about action is, why? The reason why was, it’s much easier to participate in a nonviolent movement than it is a violent one. Nonviolent revolutions tend to focus on fighting aged men, where, for instance, during the Orange Revolution, you would go to the Maidan, and you would see everybody there, from pensioners to middle-class professionals, to, of course, the younger students where it all started.

I think that, all too often, whether it’s in a marketing environment, or whether it is in a transformational change environment, where you’re trying to get an organization or a community or a society or whatever to go a different direction, I think people missed that simple, basic truth is, that you need to make it easy for people to participate, because that’s the only, that’s the first step towards commitment. You can’t expect people to just be committed and to be willing to overcome barriers to entry right from the start.

Roger Dooley: Right. If you want to hand out AK-47s and say, “Hey, you’re going to go take on some well-trained soldiers,” that’s quite a commitment on the part of the volunteer in that case. Yeah. One fascinating statistic that you quote is, that a 1% increase in participation in a campaign means a 10% increase in the chance of achieving the desired outcome. Explain how that works.

Greg Satell: To be honest, I don’t really know how that works. That comes from Chenoweth and Stephan’s research. I think it’s just a statistical numerical thing they went through. They went through these, I forget how many uprisings it was, it was well over 100, and they looked at participation, and they looked at outcomes. They just calculated that a one unit increase in participation increased chance of a positive outcome by 10%, and I think that’s … I don’t think there’s anything much more to it than that, except for an attempt by them to quantify their research.

Roger Dooley: I know. Of course, that argues to the point that you were making, Greg, but if you can get a lot of people to participate in something, then you are more likely to be successful, and you’ll have at least some of those people who will put forth higher levels of effort when it’s needed.

Greg Satell: Yeah, at least some of them. I mean, if not all of them are going to become super committed, but none of the ones who don’t participate are going to be committed. You’re going to get 0%, and I talked about a tool in the book called the spectrum of allies and how you want to shift people who are resistant to neutral and neutral to passive support and passive support to active support. You always want to be shifting people, not the whole range.

LGBT is something that, 10 years ago, everybody thought was really strange. Now, a lot of people who might have been passive resistors 10 years ago are probably neutral or to even passive support these days. I think anytime you are trying to create a change, whether that’s in a marketplace or in an organization or anything else, you have to see that progress.

Roger Dooley: A phrase that you threw out a few minutes ago, Greg, was the danger of victory. What do you mean by that?

Greg Satell: Surviving victory. So many, and this is most apparent in political revolutions, because these are very famous cases, and they are very, very well documented. For instance, in Egypt, they had the Arab Spring, but then immediately after it was over, the Muslim brotherhood got elected, and then, of course, al-Sisi took over, was at least as repressive as Mubarak ever was. We had the same problem in Ukraine, with the Orange Revolution ultimately failing in 2010 with the election of Viktor Yanukovych, and then another revolution in 2014 and 2015.

You also see it within companies and turnaround efforts, where one of the ones I talk about in the book was with Blockbuster, who, and many people forget this now, but actually Blockbuster responded quite well to the Netflix threat, and by the end of 2006 and 2007, was actually adding subscribers much faster than Netflix was, but then ultimately, of course, failed. There’s example after example. Because, all too often, we look for a change as a specific objective. Once that objective is achieved, everything falls apart.

In an organization, we say, “Okay. We want to shift to the Cloud,” or, “We want to implement lean marketing strategies.” We get that implemented in some sense, and everybody declares victory. Then, a year later, it all goes by the wayside. What I found in my research in every context is, to drive change through, it needs to be based on values and capabilities, rather than simple objectives and personas.

Roger Dooley: It reminds me of the debate over Amazon’s headquarters in New York City, where you had a bunch of activists who were protesting the plans to build their headquarters there and government support that they had received and the fact that they weren’t necessarily going to be bringing the right jobs. They were so successful that Amazon simply pulled out.

To me, it’s the dog that finally caught the school bus, and yeah, what do you do with it now? Are the long-term objectives of getting good economic development, better jobs and so on really going to be served, or will they have not only chased Amazon out, but perhaps scared off others as well who might have been willing to bring new jobs to the area?

Greg Satell: Well, I think the fear there was having some Foxcom situation, and I do think that very much in connection with your reference to Silicon Valley and Boston. You never hear about technology companies getting subsidies for locating in Silicon Valley. You never hear about banks getting subsidies for locating in New York, or entertainment getting subsidies for Los Angeles or something like that. I think it’s far more important to build up those internal networks.

For instance, in Silicon Valley, they said, “Okay. What we really need is, we need to build up our community colleges in the area, because to run these, to be able to grow these businesses, we need those middle-skill technicians in order to fuel it,” where, generally speaking, higher education doesn’t have that same effect, because anybody who is, graduates from a top university, they can go anywhere they want. For instance, in Philadelphia, where I live, we have probably the greatest finance program in the world at Wharton. Philadelphia is certainly not any finance mecca. Most of those graduates, they go to New York.

Roger Dooley: I could keep talking with you for hours, Greg. I think we’ve got so many ideas in common here all from slightly different perspectives, but I want to be respectful of your time, so let me remind our listeners that, today, we are speaking with Greg Satell, author of the new book, Cascades: How to Create a Movement that Drives Transformational Change. Greg, how can people find you and your ideas?

Greg Satell: You can always go to my personal website, which is gregsatell.com, Satell is S-A-T-E-L-L, and also my blog, digitaltonto.com, and, of course, on the Harvard Business Review website, Inc. and also Barron’s.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there as well. Greg, thanks for being on the show, and best of luck with your book. I hope you leave a few buyers out there for mine.

Greg Satell: Thanks a lot for having me, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.