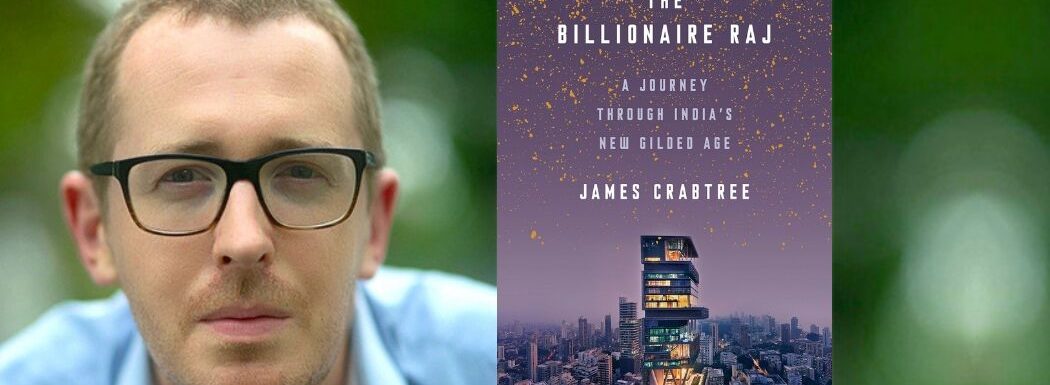

James Crabtree is a Singapore-based author and journalist, an Associate Professor of Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, and a senior fellow at the school’s Centre on Asia and Globalisation. His best-selling book, The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age, covers the rise of India’s new billionaire class in a radically unequal society and was short-listed for the Financial Times McKinsey book of the year.

In today’s episode, James discusses India’s economy, as well as what he learned from years of working for the Financial Times and leading the newspaper’s coverage of Indian business. Listen in to learn how India’s e-commerce sector is growing, what surprised James the most when talking with India’s elite, and the problem he sees with the country’s legal structure.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The current direction of India’s economy.

- What surprised James the most when talking with the elite in India.

- How his fascination with tycoons came to be.

- What he thinks of India’s legal structure.

- Whether India is an ideal place for foreign investors.

Key Resources for James Crabtree:

- Connect with James Crabtree: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: The Billionaire Raj

- Kindle: The Billionaire Raj

- Audible: The Billionaire Raj

- Amazon: Friction

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr. Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest today is a bit of a departure from our norm here. He isn’t going to tell you how to market your brand or run your business, at least I don’t think he is.

James Crabtree is a writer, journalist, and author. He’s currently an associate professor of practice at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and a senior fellow with the school’s center on Asia and globalization. His first book is The Billionaire Raj, A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age. The book was named to Amazon’s best list in July 2018, and was shortlisted for the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the year. Welcome to the show James.

James Crabtree: Good evening, Roger, or good morning where you are sir. Nice to be on.

Roger Dooley: Yes. Well you hit both ends of it. It’s early morning here in late evening in Singapore. James, I found you when I was researching my new book due out in April about Friction, which I’ll define simply as unnecessary time, effort or money needed to accomplish a task. Part of the book relates to customer experience and shows how companies like Amazon and Uber and smaller companies, have prospered by greatly reducing customer effort. Other parts of the book look at friction inside businesses, wasted time in meetings, dealing with pointless procedures and such, and at the national level I write about bureaucracy, red tape and how countries compare in ease of doing business. And in doing my research, I found a story about cats that you wrote. Why don’t you sort of set the stage and explain your cat story?

James Crabtree: Yeah, it’s an interesting way into the book, so The Billionaire Raj in general is a book about the rise of India’s new super wealthy, but it looks across the piece at India’s tycoon class, and in a sense how you do business in India, whether that’s selling products or simply transacting. And so one of the famous things about doing business in India, or the easy place to start is it’s very difficult compared to doing business in Europe or America. The barriers to success are very considerable, bureaucratic barriers, logistical, infrastructural whatever you like. And dealing with the government is a big part of that, and so this brings me to the cats. So I, when we moved to India, we brought with us two Maine coon cats, Maine coons are very fluffy, furry cats specifically bred for cold climates. So you can imagine they didn’t, you know, they’re not very well suited for the hot heat of India.

James Crabtree: When they came into the country from the UK, this was a painful process. But when we were trying to take them out, when we moved to Singapore, it was a really, very painful process. And that was partially because India is so bureaucratic that you’d have to hire middlemen to get round the bureaucracy. So India is awash with middlemen, and so one of the teams I talk about in the book is corruption. And one of the aspects of corruption in India is the proliferation of middlemen in all sorts of things, if you want to buy missiles or coal or if you want to get your cats out of the country, you often have to hire people who know how to navigate the system because the system is so, so painful.And so in the book I recount a story of of having to drive out of Mumbai on a one day to go and get, you know, the 19th pointless form signed that I needed to get signed.

James Crabtree: And realizing that the inner center, one of the problems of this very bureaucratic system was it created huge opportunities for incidental corruption and that the more bureaucratic the process was, the more forms that needed to be signed, the more opportunities there were for, for graft, and not really being able to work out in my own case, whether some of the fees that I was paying to my middlemen to get my cat’s out of the country were going on bribes and if so, how much, and whether what I was really doing with the middleman was getting a kind of bit of plausible deniability. So I could say, well, “I didn’t pay any, I didn’t have to hand over any cash.” I could be kind of, plausibly ignorant of what was going on around me. And so in the end I never really found out whether taking our two cats out of the country did involve lots of favors and backhanders or not, but certainly that is something that happens in India a lot. And it’s one of the reasons why it’s such a difficult place to do business.

Roger Dooley: How far along where you with your book when you went to India, were you already working on it and planning it? Or did the concept occur to you when you were there?

James Crabtree: Oh, no, no. I mean I knew almost nothing about India when I moved there. So I’m a classic foreign correspondent in the sense that a, I’m not a lifetime India expert. I mean, I’d been to the country a few times. I could find it on a map. I wasn’t totally ignorant. I had read a few books, but when I turned up in Mumbai, I mean I was still starting from scratch and in a sense, through the themes of the book to some degree, followed on from that. One of the things I became most fascinated about where tycoons as a class, so the subtitle of my book is A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age. And so if you live in Austin, Texas as you do on London, England, as I did before I moved, there aren’t really tycoons in any more. I mean you have Elon Musk and Richard Branson and a few characters who have kind of tycoon like qualities, but this isn’t the same as Cornelius Vanderbilt or Jay Gould, or the the great figures of antiquity in Western business.

James Crabtree: But in India, in many other western countries, you do have proper authentic tycoons who sit across sprawling, family owned conglomerates and some have the kind of power or an agency in the business world that is much greater than your average corporate chief executive, you know, in London or New York. And I became fascinated by these figures, I’d never really come across them before in my previous life, both as a journalist or a sort of, policy analyst. And so, part of the joy of living in Mumbai was getting to see these institutions up close, getting to know the tycoons themselves. And so it was out of that, you know, my interest in India’s business elite and the extraordinary amounts of wealth that they were creating, but also the problems that came with that, particularly of corruption. That was what got me interested in this idea that India was going through a phase in its development, which was quite similar to America’s gilded age well over a century beforehand.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it really does seem like a good parallel. Even though we do have some ostentatious billionaires now, they really aren’t like, as you say, the Vanderbilt’s where they built a massive castle like Biltmore House in North Carolina. Although even Biltmore House, it was probably a drop in the bucket compared to the skyscraper mansion. Explain about that James?

James Crabtree: Well so yeah, so you’re talking about a building in Mumbai called Antilia, which is the home of Mukesh Ambani, who is India’s richest man. Now, the Ambani’s, I don’t think are that well known in the UK or the US, but in India, you know this is the preeminent business dynasty of the country. India has been through a period of extraordinary change since it opened up its economy in the early nineties after decades of socialism and in a sense, little engagement with the outside world. But there has been over the last 20 years, one rock of stability, which is that the richest person in the country, has always been an Ambani, first Mukesh Ambani’s father, and then when his father passed away in the early two thousands, himself, and when he inherited the business from his dad, he set about building for himself what has been called a vertical palace. It’s a 170 meter tall residential skyscraper in downtown Mumbai, it’s one of the tallest buildings in the city to known as the billion dollar home for what it is rumored to have cost.

James Crabtree: And so this is a family home for him and his wife and their three children, you know, and their seven stories of cars and you know, all the kind of absurd acute trauma that come with being a man who has a fortune $45 billion, and this in a city that half of the population by most estimates live in slums. And so if think about all of the cities in the world that embody a certain kind of extraordinary wealth and to some degree inequality, whether that’s, you know, New York or Beijing or Moscow or wherever it might be, there’s nowhere really like this building. It’s a unique kind of, example of a very rich and successful business person building themselves an entirely new type of home that stands to my mind, as a kind of metaphor for what has been happening in India over the last ten or 20 years, which is that the super rich have created wealth at a rate that is as quick as almost any country in history, perhaps on a par with Russia.

James Crabtree: And although some of those rich people have done that in a way that’s very admirable by building great global businesses, competing in global markets, winning customers and making great products. A good number of them have not done it that way. They’ve done it through political favors and knowing how to work the system and something that’s much closer to the definition of crony capitalism rather than competitive capitalism. And so that is also the tension that I talk about in the Billionaire Raj. That India is not Russia, it has plenty of globally competitive businesses. It has a fantastic tech sector. You know, there’s a lot to be excited about in Indian business. But on the other hand it does have a kind of, dark underbelly and learning how that dark underbelly operated or you know, what was there was something I was very interested in.

Roger Dooley: What do you see as the direction now in India, are things getting better? Is some of this cronyism declining, is the bureaucracy improving at all? Is there less red tape? It seems like when Modi came in, part of his objective was to make it easier to do business in India. Is that working?

James Crabtree: Yeah, I mean you’re completely right about that. So the idea of the ease of doing business survey, the World Bank survey, with the goal in India to improve India’s ranking. India ranked very poorly on that, on some of the sub rankings. It was as close to the worst in the world, you know, in the 180 out of 186 nations on some measures. And so they have made some progress, actually I own rates of ease of doing business, India has improved quite a lot. It’s jumped up to I think something around 70 or 80th place. There are various problems that some of your listeners might associate with India, which are really not so true anymore. Nationwide power cuts were common not that long ago, actually now power cuts in India are relatively rare, that has been fixed, there simply aren’t that many poor people in India anymore. So by which I mean dirt poor and you know, people living on $2 a day or below, that kind of abject poverty is disappearing as it is in most of Asia.

James Crabtree: And so what you’re sort of getting towards, you know, not a kind of desperately poor country but a lower middle income country. And yes, some of the worst of the corruption scandals have also stopped, there haven’t been quite as many multi billion dollar scandals as there were in the decade before the financial crisis. Nonetheless, I mean India is still a country that is beset with challenges. It’s still a very difficult place to do business. It’s a difficult place to be a foreign investor. You know, investors from the US or other advanced economies who try to invest in private equity in India for instance, don’t tend to make any money because it’s risky, finding good partners are hard. Indian business landscape still requires very careful skills to navigate. So it’s complicated. You know, there is some progress, but still sit in the situation is progress is not as quick as many in India would like.

Roger Dooley: Yeah the world economic forum data is good but I don’t know that it always tells the entire story, it shows that China for example is a moderate, not quite as difficult to do business in is India perhaps, but not particularly easy either. But on the other hand, there’s a kind of a duality, if you or I wanted to set up a business there it might be challenging, but if something is being done by a government controlled or company that the government is interested in making progress, stuff can happen very quickly and easily there just simply because it’s quite autocratic and you don’t have a legal system that can challenge everything. I mean, trying to get an infrastructure project done in the United States, particularly in an urban area is next to impossible, at least in any kind of a normal timeframe, infrastructure projects can proceed quite readily in China, it seems. How good do you think the World Economic Forum data is?

James Crabtree: Well that point you just made about the US and China is a very good one, and India would definitely fall in the US bracket and more so it’s very difficult because of India’s democratic politics to execute the kind of development approach that China has done. So people in India have real Chinese road and high speed rail envy. They wish that India was able to do what China has done. But as you say in a democratic system that that’s noisy and complicated and where people complain, and there’s MP’s and parliament, this stuff is difficult. And so that side of India doesn’t work that well. Nonetheless, that doesn’t to my mind suggest that you should definitely want a more autocratic kind of country, that’s a rather different suggestion, although one that you will hear in India. As I say, I mean people that there are some people, business people who, who sort of feel, I think wrongly, that you should trade it in a little bit of your democracy for a bit of kind of East Asian autocratic rigor and that would get you a jumpstart on, on development.

James Crabtree: And that may be right in the short term, but you’d give up a lot to go with that. So in the end, I think India’s development and you know, foreign investors who are thinking of looking at India sort of have to get used to the fact that this is a more complicated story in some ways than China. If you look at the way that foreign investors, particularly, silicon valley investors, look to invest in the Indian tech sector. It’s a very good example of this. So there was a lot of excitement about Indian tech off the back of the Alibaba IPO. So when that happened, a lot of people who invested in Alibaba or people who wished they’d invested in Alibaba early looked around and thought, “Okay, well let’s get in on India. It’s another market that has a billion dollars, you know, middle class rising Asian giant, you know, good tech sector, let’s all go big.”

James Crabtree: And so for a few years in 2012, 13, 14, there was just a ton of money that came into the Indian equivalent of Alibaba and Ten Cent, you know, that the Indian Amazon competitor, the Indian Uber Competitor, and yet very few of these investors have made much money because the speed at which India’s E-commerce sector is growing is just much, much slower than than China’s. China’s started earlier, it had a lot of advantages. The system is less bureaucratic. The Chinese middle class at that time was much bigger and so India has simply proved to be a more complicated place for foreign investors to operate and one in which if you aren’t going to get a return, it tends to happen in a more longterm, often more kind of chaotic fashion.

Roger Dooley: Well I guess India was kind of both blessed and cursed by inheriting the British legal system too, you know, there’s definitely the rule of law there, but it’s kind of convoluted, it seems.

James Crabtree: Well, you know, I don’t want to instinctively defend my countrymen here. So the British record in India is a pretty dismal one in all sorts of different ways, but I’m not sure it’s specifically the Britishness of the legal system that is the problem. I think you could have inherited the American legal system and if you put no money into it and didn’t fund it and didn’t kind of, give it the resources that it needed to process cases, then no legal system would work well. The problem with the Indian legal system is not it’s fundamental structure. The fact that it is a kind of common law tradition inherited from the British as opposed to some other system. The problem is that there’s no where near enough money and sort of, technical expertise which goes into making the system work. So the backlog of cases, I forget exactly what the figure is, but there’s a figure that is fairly widely quoted, which says that if India’s legal system took on no new civil cases, it would still take 350 years to clear the backlog.

James Crabtree: And so there’s just a huge overcapacity issue, which is partly because, as you say, you have a legal system which allows people rights and so people will kind of, launch suits on all sorts of different, you know, land disputes, all sorts of little things much as you would in America. I mean, India is a very litigious culture, but it then has a legal system which is completely unable to bear the brunt of that demand. And so yes, as I say, I don’t think particularly in this case, it’s the kind of British structure that is the flaw. The problem is that the legal system gets nowhere near the resources that it would need to cope with the demands that are placed on it.

Roger Dooley: I’m curious, James, as you were researching the book, you were able to interact with at least a few of these tycoons, how difficult or easy was it to make that happen?

James Crabtree: Well, actually I would say that I’ve sort of met almost all of them. Compared to China, India is a delightful place to be a journalist. It’s much more likely United States in the sense that it’s an open society. You know, not a perfectly open one, I mean it’s not Scandinavia, but people will talk to you. Indians are famously talkative and you know you can go and meet people. There are a few people if you are determined that you can’t go and see, so I never got to interview Narendra Modi, which was, that was one thing that I should probably have done. But you know, I met many other of the most senior politicians in the country and almost all of the billionaires that I wanted to meet, I met at one time or another.

James Crabtree: And so that’s very different from a country like China in particular, where it’s incredibly difficult to get access to the top levels of the political system or the business elite. And if you do, the odds are they won’t tell you anything interesting anyway. India is quite quite different. It’s also very well, it’s a very global society in its elite, in America you have the Indian diaspora, the Indian diaspora here in Singapore and London, which is very successful, the richest per capita religion in the United States is by many measures Hinduism, certainly the best educated religious minority are Hindus. And so that diaspora and the fact that the Indian elite, you know, they have houses in London, they send their kids to American universities on the east coast. They’re very globally integrated, both in terms of education and access to capital.

James Crabtree: And so they care what international community thinks about them in a way that is much more profound, I think, than the Chinese elite or kind of, elites in East Asia. And so that just meant that, yeah, going to India is a great joy. It’s a wonderful country to report in, it’s great fun. You don’t have to learn it prohibitively difficult foreign language because most of the elite already speak English. And so in that sense, I felt that, I got great access and the stories in the book, the kind of up close and personal portraits of some of these most controversial tycoons and politicians and other figures in kind of ,Indian public life, the media, cricket stars, whoever it might have been that I was talking to, I was able to go and meet these people and that was one of the things that made the book worth writing.

Roger Dooley: Did anything surprise you as you sort of got behind the curtain with these very, very wealthy people?

James Crabtree: I mean, the thing that often struck me about them was how they themselves did not see themselves as all powerful business titans. They sold themselves as, if not victims, than people who were very constrained and struggling against great of diversity. So if you were to look from the outside and you were to compare an Indian business tycoon with their equivalent, you know, Wall Street chief executive, you might think, well these people have enormous amounts of power. They run many different businesses, they have often, their businesses are not listed, even if they are listed, they control huge equity stakes. Indian tycoons love the equity. And so they have great control over that enterprises and often they have advantages of being able to, you know, work the political system in ways that simply wouldn’t be true in the West. But actually if you’re go and talk to them, particularly when I was talking to people in a time in the business cycle when a lot of these tycoons were struggling a little bit.

James Crabtree: So part of the story of the Billionaire Raj is about the kind of boom and bust that happened in India. The boom happened in the mid two thousands and they’re still kind of recovering from that today that there was a huge asset bubble in the run up to the financial crisis. And so still today a lot of the challenges that the business community in India faces are to do with the bad debts that were built up and that still infect the banking system. So I was talking to some of the tycoons who were coping with that. But even more generally there was just a sense of how hard it was to do business in India. You know there were always sort of, hungry mouths to feed that there was a politician who wanted you to do this. There was this group that wanted to help with this. You were trying to build this steel plant or that oil refinery and all of your plans were being kind of stuck in the mud of bureaucracy.

James Crabtree: And then if you’re an Indian business tycoon, you have much wider social obligations often than you would if you’re a business person in the West. So you have obligations to the communities that your factories are in. You sometimes have a sense of obligation to the cast group that you have come from. So yeah, in all of these cases I was often rather struck, one of the things that always interested me was who were these people, the tycoons, what were they worried about? What kept them up at night?

James Crabtree: And often I had this sense when they kind of opened up a little bit that as opposed to feeling that they were all powerful, they actually felt that they were hemmed in and constrained. And I rather liked it when they talked about that because it gave a much more human conception of what it was to be a business titan. Which is that this is a very hard thing to do. You know, you have a lot of responsibilities and a lot of obligations. You do not have kind of untrammeled ability to do what you want. And the people who are skillful at it are the ones who are able to manage these very different sets of demands that are being placed on them, you know, demands from their bankers, from their workers, from their wider communities, from the political class. You know, there were all sorts of balances that needed to be made and I always thought that was rather interesting.

Roger Dooley: Now James, one of the things that the Indian government tried to do a couple of years ago was reduce ease of being corrupt or of operating informally by taking all large currency bills out of circulation and saying these aren’t going to be good for anything anymore. And I’m not sure , it seems like at the time I thought it was about anything bigger than roughly a US ten dollar bill would not be valid. And with the thought that it’d be more difficult to make payoffs to people or just for a business to operate outside the economy because theoretically at least electronic transactions would be able to be monitored better than wads of cash. Were you there during that time? And I’m curious how that worked out?

James Crabtree: So this is called demonetization monetization, is the phrase that tends to be used. And so I was in India during the time that it was happening, but I wasn’t living there, by that time I’d moved to Singapore, but I was going back and forth on reporting trips to research the book. And so I was around in India, so I saw the lengthy queues of people lining up at cash machines. I heard shopkeepers complaining about what a disaster this had been for their businesses. At the time it was a curious thing, so this measure, which on the face of it look completely crazy and economically illiterate, was actually quite widely supported and people liked demonetization and they liked it for a particular reason, which was sort of the theory behind it originally, was to do with something called black money.

James Crabtree: And black money is a term that is used rather loosely in India to mean anything from a transaction upon which you should have paid tax but you didn’t. So let’s say you bought a house or you even bought a pair of trousers and you do it under the table as opposed to through the formal channels. And so nobody has to pay any tax, so the money that went into that is black money because it’s not being registered with the tax authority. But it also runs the gamut to outright criminality. And so there is a sense in India, a completely accurate sense that there is a vast amount of this that goes on. People from outright criminals for the respectable middle class, you know, do a lot of things to avoid paying tax. And so the idea was that if Modi got rid of all of this money at a stroke and replaced it all, then a lot of people who were meant to be sort of, hoarding illicit money literally in suitcases under their beds, would suddenly find themselves kind of caught out, the music would stop and they would then have to fess up to the fact that they had all this illicit money.

James Crabtree: And so that was the image that people had in their minds. And, and actually the fact that Modi appeared to be going after people who had illicit funds was very popular. It showed the depths of public anger about corruption in India. So you had this list of kind of people who were thought to be being punished for this who were, you know, bribe taking policemen or corrupt politicians or dodgy billionaires. But actually of course, none of these people were remotely affected because the idea that people kept large amounts of money in suitcases under their beds turned out to be a myth. I mean, if you were indeed corrupt in some efficient way and you’ve got lots of black money than you recycled it very quickly into property or gold or probably equities.

James Crabtree: And so it turned out that this measure, cut a long story short was just as crazy and in fact, as it looked initially, it did a lot of economic damage for very little gain. I mean, there were some minor gains, but that’s often true with very destructive things. If you have a natural disaster like an earthquake, it’s quite good for people that have to rebuild afterwards but it doesn’t mean that you should welcome it. And so in the end, actually the damage that it did to India’s economy was about the same as a very bad natural disaster. So it knocked a couple of basis points off GDP for two quarters. And that’s roughly the same as you would get if you had a really bad natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina or something like that. So the the amount of damage it did was enormous for very little benefit.

Roger Dooley: Well, India has always had a really big informal economy in you see that gradually transitioning, is formal academy growing more quickly than the unreported stuff?

James Crabtree: Yeah, I mean that’s an enormous, both an enormous challenge, but also the direction in which India’s economy, I’m sure we’ll go. But at the moment it’s for the formal sector, so look, if you take it in terms of tax paying jobs, the number of Indians who pay income tax, which is an indicator that they have the kind of job that you or I might have in the formal economy or even a job in a factory, very small, maybe 20 million out of 1.3 billion who pay income tax. So the tax base is tiny. And so one of the big, India is going through at the moment, a few real mega transitions as it changes from being poor agrarian society to being a much more urban industrial, to some degree postindustrial society.

James Crabtree: And so there’s a huge urbanization challenges, there’s hundreds of millions of people are going to move from villages to cities over the next 20, 30 years. One of the biggest movements of humanity ever, but the, the movement from an informal economy to a much more formal economy is almost a kind of, comparably grand challenge. And so that gets back to some of the things probably that you’re talking about in your own work, that if you want people to move into the formal economy, it’s critical that you make that process as easy as you possibly can. And that’s one of the big challenges in India that all sorts of things that in more advanced economies are much easier, starting a business, registering for tax, pushing through a criminal case, they’re very, very difficult still. Some people hope that technology might be something of a kind of magic bullet, that you could move some of these processes online and make them much more efficient and there is something to that. But nonetheless, this move from an informal to a formal economy is one of India’s great challenges.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, James, just one last question, I’m visualizing you flying back and forth in between the Singapore and say, Mumbai, and you must experience culture shock every time you get off the plane. There’s such a contrast where Singapore seems to be such a smooth running machine, is so clean, everything works perfectly. Is that the case?

James Crabtree: In what sense? Sorry …

Roger Dooley: Well just the contrast between the two. Like if you wanted to pick a country where there’s a lot of disfunction and chaos. Not that India is a bad place, but I mean it’s just very clogged with traffic, lots of poor folks, lots of rich folks. Where Singapore just seems to be a very highly organized country.

James Crabtree: Yeah, I mean, so coming here was helpful in my writing the book in a number of respects. So yes, as you say, Singapore is kind of the anti Mumbai. Which, so I lived in Mumbai, I was the Mumbai by bureau chief for the FTE. So that’s what I wrote about. And so Singapore is everything that Mumbai is not, but in a kind of broader sense, moving to Singapore to write the book was quite helpful because it helped me to place India within a specifically Asian development context. So I knew less about the sort of, development trajectory of of Asia starting with Japan and Korea and Taiwan and Hong Kong and then through some of the Asian tigers and the model of development that they had followed, which was, you know, a particular story to do with the importance of infrastructure investment and low cost export manufacturing in particular.

James Crabtree: And so I learned something that way as well about in a sense, the journey that Singapore is, I think probably the most successful of all of the Asian economies. And you can argue the toss between Singapore and Japan, I suppose. But I think Singapore is probably the most miraculous development story because Japan was an already a kind of, relatively advanced after the Second World War. Where is Singapore had, you know, not much. And so it helped me think about India is likely to have to do as it tries to develop by learning, you know, from some of the more successful examples elsewhere in Asia as well as thinking about the comparison that I mentioned earlier between India now and and America and its own gilded age. And so in a funny way, I conclude the book by saying that it’s an optimistic book and a number of people who, so when the New York Times reviewed the book, one of the things they said was that I claimed that the book was an optimistic work, but actually if you read it, there wasn’t very much to be optimistic about.

James Crabtree: The reason why I’m optimistic is that if you were to look at America in the 1880s or you were to look at Korea in the mid 1960s, you know, you would have seen economies that had enormous challenges that are very similar to the ones that India have today. You know, rampant illegality and corruption, a kind of super rich class that appeared to be completely feckless and uncaring and only in it for itself, all sorts of problems. And in the end, all of these countries managed to overcome them, not in a year or two. But over the course of a generation when you had progressive political reform, good business regulation, you know, some of the problems that appear to be insurmountable in the short term turn out to be reasonably manageable in the kind of medium to longterm.

James Crabtree: And so I think, you know, it doesn’t mean that all of this is going to happen by magic, but it also doesn’t mean that one should be fatalistic about a country like India. In a sense, I think in the longterm, India’s future is bright. The world is going to be an awful lot more Indian than it is now just as it is going to be more Chinese than it is now. And it’s important that all of us learn more about India and how its economy works because I think that’s going to be a big part of all of our futures.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, one way to do that James, would be with your book. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with James Crabtree, author of the billionaire Raj, A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age. James, how can people find you and your ideas?

James Crabtree: You can add me on LinkedIn. I’m always happy to meet new people on Linkedin. I have a website, JamesCrabtree.com, or I’m on Twitter, so any one of those things would be absolutely fine, it’d be great to meet a few of your listeners.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well we will link to those places and to any other resources we spoke about on the Show Notes page at RogerDooly.com/podcast we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. James, thanks so much for accommodating the time difference and being on the show.

James Crabtree: Thanks so much. It was really nice of you to have me on.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book Friction is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to rogerdooley.com/friction.