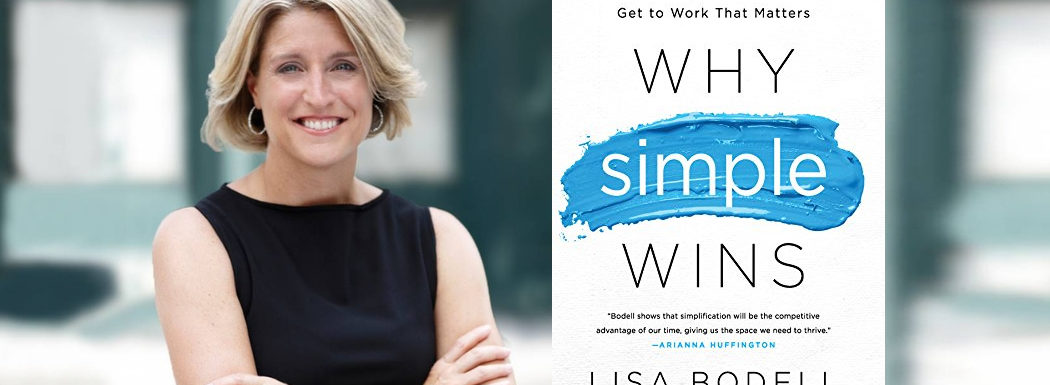

Lisa Bodell is an award-winning author and CEO of FutureThink, an innovation firm that thrives on simplicity. A futurist and expert on the topic of change, Lisa’s mission is to provoke fresh thinking and help people solve problems in intentionally simple ways. She has appeared on NPR and FOX News, and has been published in Fast Company, The New York Times, and WIRED.

Lisa Bodell is an award-winning author and CEO of FutureThink, an innovation firm that thrives on simplicity. A futurist and expert on the topic of change, Lisa’s mission is to provoke fresh thinking and help people solve problems in intentionally simple ways. She has appeared on NPR and FOX News, and has been published in Fast Company, The New York Times, and WIRED.

In this episode, Lisa shares insights from her book, Why Simple Wins, including how complexity issues not only hold companies back, but can also cost them money. Listen in to learn where many complexity issues start, how Lisa gauges these kinds of problems in the organizations she helps, and what you can do to start identifying similar issues within your own organization.

Learn how complexity issues not only hold companies back, but can also cost them money with @LisaBodell, author of WHY SIMPLE WINS. #change #innovation #corporateculture Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why simplicity is so important.

- How trying to solve problems often leads to complexity.

- What Lisa looks at in order to gauge complexity issues within organizations.

- A simple way to get started reducing complexity issues within your own organization.

- Success stories of businesses that reduced complexity and prospered.

- What friction is and why we should aim to reduce it.

- Where leaders can reduce friction.

- Why trust is crucial within organizations.

- How lower-level employees who see a need for change can get management to buy into the need for simplicity.

Key Resources for Lisa Bodell:

-

- Connect with Lisa Bodell: LinkedIn | Twitter

- FutureThink: Website | Twitter

- Amazon: Why Simple Wins

- Kindle: Why Simple Wins

- Audible: Why Simple Wins

- Trust Factor: The Key to High Performance with Paul Zak

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book Friction is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. I found today’s guest while I was researching my new book, Friction. Stay tuned at RogerDooley.com for more info on that.

I found that Lisa Bodell’s philosophy is very much in tune with my own. Not only that, her strategies and tactics are very practical. She’s the CEO of Future Think, a consultancy that among other things teaches simplicity. Lisa is the author of the bestsellers Kill The Company and The Book That Led Me To Work: Why simple wins. When she’s not running her company and writing bestsellers, Lisa serves on the Global Agenda Council of the World Economic Forum in Davos, and is an advisor on the boards of the Association of Professional Futurists. And she’s taught innovation and creativity at both American and Fordham Universities. Lisa, welcome to the show.

Lisa Bodell: Thanks for having me, Roger. It’s a pleasure.

Roger Dooley: Great. Lisa, you went to the University of Michigan, which as a Notre Dame fan bothers me a little bit, but that’s okay. And then you went into advertising. How do you get from the ad business into being a futurist and simplicity expert?

Lisa Bodell: Well, it’s interesting. I always say it’s strategic luck, which is, I had no intention of being where I am, but events led me that way when I finally figured out what my strengths were. I always say I’m a recovering ad agency person, which was the first job I had out of school. But it really taught me the business of creativity in how important soft skills are versus just hard skills. You need the balance of both to be successful.

I happened to look into … This was in the late 80’s, early 90’s, running a dot com, and that taught me entrepreneurship. And then I finally went off on my own and I wanted to be able to be more in control of my life and be entrepreneurial on my own, versus at somebody else’s company. And I started really interacting with interesting people and with a stroke a luck I was visiting my grandfather in Michigan … A small town in Midland, Michigan, and there was a futurist there who was leading future efforts. And I said, “I’m going to be in town. You want to meet for coffee?” He said, yes, and this whole world opened up to new in terms of what a futurist is, how people connect in different ways. And it was interesting for me because that was right around the time when it was okay not to have a linear resume anymore, and it really introduced me to people that were doing things that were uncommon and it struck chord with me and I started my business to do the same thing.

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s great. I think it’s a great illustration for our audience, perhaps even for those younger members of the audience who are earlier in their careers, that probably very few people’s career has gone exactly as expected and that probably most of us are in a different place than we anticipated being, particularly in today’s world. I mean, when I was a kid, people stayed with one company for their whole life. They had a plan and maybe they didn’t get to the exact position they wanted or they ended up at a different branch or something, but things were fairly predictable. But today, that’s certainly not the case. And I would guess if you talk to almost anybody who’s well into their career, they would say … Point out little strange occurrences like you did. A chance meeting, a magazine article they read, or something that ended up changing the direction of their life.

Lisa Bodell: Absolutely. That’s why I say strategic luck, because I don’t want anyone to think it’s just a crap shoot. You don’t just go off and go with the wind. It’s nice to have a plan and to figure out what your strengths are and learn from expertise. But it really is … It’s being open and really doing unconventional things that I think are the people that get ahead, and frankly, are the ones that are better to keep up with the pace of change. And that’s what’s different than probably when you and I got out of school is that, there aren’t really linear career paths anymore, and those that have had lots of different eclectic experiences are going to be more valuable I think in the future.

Roger Dooley: Obviously, too, the more entrepreneurial you are, the more you’re likely to get into these more unusual career paths where you find an opportunity … One opportunity, and then through that you discover an unrelated opportunity that is perhaps even more attractive. Anyway, that’s great advice, but we’re not a career help show here. But I think it’s really important for people to recognize that. Lisa, when we think about evolution, we think about organisms getting more efficient, more adapted to survive in their environment. But with companies, it seems as they evolve, they evolve into complexity and a less survivable situation. Is that what you’ve found?

Lisa Bodell: Yeah, it’s interesting because I feel like we create the beast that we become a slave to. And what I talk about with complexity is, everyone has the best intentions. I think most complexity is unintentional. People are trying to solve a problem. They’re trying to move quickly. What they do is they build on top of what might already be a suboptimal system. Again, best intention, but over time that builds a callous. It creates a worse situation. I always talk about to new companies that they can put the right behaviors in terms of question the way we work, revisiting rules, and killing those that get in our way before they become habits or assumptions. That’s great for a young company as they grow.

For established companies, it’s recognizing that just because it’s how you did it before doesn’t mean that’s how you’re going to do it going forward. And again, changing those behaviors is a little bit more complex because they just have scale, but companies can do it. There are large companies like your Googles, your IBM, even your John Deere’s that look at their company … They’re over 100 years old and they say, “You know what? We’re going to be able to change this and embrace simplicity as a strategic point of view, not just … I don’t know. A 12-step program.”

Roger Dooley: Right. I’m originally an engineer, speaking of strange career paths, and both physicists and engineers talk a lot about entropy, the tendency of things to become disordered over time. And engineers probably take it a little bit farther to thermodynamics, but it seems like maybe companies are fighting entropy, but they start off fluid and flexible and they end up becoming more ordered with structures and hierarchies and so on. In one sense, they seem to be the opposite of what we think of as entropy. But I guess that’s just the way it goes.

Lisa Bodell: Well, one thing I like to talk about with people is, you need structure. I mean, everything can’t be chaos. But at the same time, it’s more about keeping people in the swim lane with guardrails, not handcuffs. And unfortunately, people tend to go to the extreme. Rather than putting in a couple of rules, they put in 12. Rather than putting in a process, they make it a big complex org chart. It’s like when people say, “You know what? Let’s simplify meetings.” This is a true story. This happened last week.

I’m working with an organization. They said, “We’re going to simplify meetings.” And they put a group together to write down what the approach should be to tell people to do that, and they came up with a 100-page handbook on how to simplify. And what they forgot was, can you imagine rolling out a 100-page handbook to a group of adults? It’s insulting. And the reason that is, there’s a lack of trust. In our best intentions to try and solve a problem, then we overthink it. We put in way too much handcuff versus guardrail, and then you need to trust the people. The majority of them will do the right thing, and that’s where people get a little lost. We feel like we’re designing for the one bad apple versus knowing that 99% of the time, if you give people leeway, you tell them how you want them to run it, they’ll do the right thing. They don’t need the 100-page handbook.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. That 100-page handbook sounds like a symptom of a company that needs some simplification. The fact that this would be the way to simplify things, that tells you something right there.

Lisa Bodell: Yeah. But it happens more often than you think. By the way, the next thing they were going to roll out was how to write an email. And I said, “Guys, stop.”

Roger Dooley: They could probably do that in about 150 pages, I think.

Lisa Bodell: Yeah, that’d only take 150. But can you imagine, Roger, someone sends you a little dossier on how to write an email? That’s insulting. Again, it’s really thinking through the human factor of it. Understanding that people have the best intention, addressing the problems of what they can and can’t do, and then let them fly. I mean, you can adjust along the way, but 100-page and 150-page handbooks, you’ve just created the beast you’ve become the slave to.

Roger Dooley: Well, I think you make a really good point there, Lisa. In Friction, I talk about how … Well, my use of the word friction, for those folks who haven’t heard it yet since this is a relatively new topic for the podcast at least, is wasted time, effort, and money. And particularly wasted effort, whether it’s in the customer experience side or in the internal operations side. But one thing that I’ve found as I was researching the book was that trust is really important if you want to reduce friction, and it played out in so many different situations. I’ll give you an example from my own work experience that made it into the book.

I’ve been an entrepreneur for decades, but some years back I built a business and I co-founded and sold it to a large company, and as part of the deal I became an executive with the company for a few years. And I had to abide by their rules and procedures, which was novel for me as a longtime entrepreneur. But they were good people and there wasn’t a problem. But their expense reporting system was really wild. There was a receipt requirement for every single expense. If you bought a $2 coffee at the airport, if you can find a $2 coffee at the airport, that had to be accompanied by a receipt if you wanted to be reimbursed for it. Even a relatively short trip would have this big stack of paper to accompany it. And I always wondered, well, does anybody actually look at this stuff? Certainly, that would be a huge waste of time.

And one time I lost a receipt somehow on the way to stapling it to the back of the paper, and somebody actually … Accounting bounced it back and said, “Hey, you’re missing this $3 receipt here. You need to either fix it or remove it from your report.” And I thought that was … In the grand scheme of things, it wasn’t a big deal. It didn’t take me that much time and that was the way they want to do it. But later on, I wondered about that as I was writing Friction and I said, “Why did they do that?” And I tracked down the chief financial guy from that time who was also long gone from the company, and I said, “Why did you guys have that requirement?” He said, “Well, there was a feeling that we couldn’t really trust everybody to not abuse the system. That there would be some people who would absent that requirement, inflate their expenses.”

And there probably could be a few of those, but that lack of trust was what caused this procedure that created a huge amount of work for everybody in the company, as well as in accounting, where they probably had to have at least one or more people dedicated just to keeping track of all that stuff, when a little bit of trust would have gone a long way. It wasn’t a legal requirement at all. The IRS has a much more liberal requirement on that.

Lisa Bodell: That’s right. Well, that’s what’s interesting is that … I’m sure people did check it. But the point is, should they have? I mean, isn’t there a better use of their time? And, how much was really getting abused? I mean, it’s a cultural decision. It’s an ethical decision. It’s a financial decision. It’s many of those things, but I think you bring up an interesting point, which is … I talk about with simplicity, it’s evil twin complexity. Complexity is largely driven by fear because people are worried about losing their job. They’re worried about not appearing valuable. They’re worried about the politics of things. Fear drives a lot of why we do what we do.

What’s interesting, and I want to tie this back to your book Friction is, when people really listen to my speech, when I talk about why simplicity is so important, I would say the number one job of a leader is to reduce the friction. And people really open their eyes when I say that because what they expect is, their number one job is to drive vision, is to create shareholder value. It’s not. Their job is to reduce the friction so everybody can do it. And if they don’t do it, nobody else will, because leaders set the signal. If I was a leader right now, I would concentrate really hard on, how can I reduce the barriers, the excuses, the unnecessary complexity so people can do more valuable work? That’s my job as a leader, and that’s why they need to start paying attention to this topic of friction, because when you reduce it, great things can happen.

Roger Dooley: Technology is supposed to make things simpler or easier, Lisa, but I’m guessing that’s not always the case. I know certainly sometimes technology can be really complex and frustrating, and even good technology could have unintended consequences. Email made communication really simple and easy, so it took a lot of the friction out of that. But at the same time, communication was so easy that now we’re getting 100 times as many inbound messages as we were back in the day when somebody had to actually hand you a piece of paper.

Lisa Bodell: Yes. I mean, that’s the … The difference is not the what, it’s the how. Email is great. How people use it is not. It’s interesting. We spend a lot of time in companies talking about, what are the complexities that really hold people back? And it’s not rocket science, Roger. It’s meetings and emails and reports and the things we create. It’s not what people say. Regulation. Organizational structure. Yeah, those are a problem. But the things within our sphere of control, a lot of that is the complexity that bogs us down, and it’s how we’re using things.

Let’s use your tech example. People will say to me, does technology help us or hurt us? The answer is yes. That’s exactly your point with email. It has absolutely helped us, but how we’re using it has hurt us. I spend a lot of time giving advice … It’s interesting. They pay me a lot of money to come and speak about how to simplify, and the stuff I’m spending a lot of time answering questions on is how to improve their inbox. How to make people run better meetings. I mean, this isn’t rocket science, but it’s, how do you get people to change their behavior so how they do it is more efficient? They don’t want to stop meetings, and you shouldn’t stop meetings. That’s a great way to collaborate. But how they’re spending the time doing it is just a waste. Let’s refocus on the how, not just the what.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think meetings are really the bane of today’s existence in a lot of organizations. People feel a need to be there and be part of something, but at the same time you’ve got half the group that’s either checking their email or doing something else because we know whatever’s being said isn’t directly relevant to them, and just really a horrible waste of time for everybody.

Lisa Bodell: Well, it’s interesting. I said, “The next book I write, I’m going to have a whole chapter on email tips and a full chapter just on meeting tips.” And I guarantee you, I will have spent thousands of hours researching another topic on simplicity, and what are the two chapters people are going to focus on? Meetings and email. I mean, it’s simple things like just changing their frequency. Meetings are for decisions. Emails are for information. Telling people, “No need to respond when I send you information.” It’s that stuff that helps people out a lot.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, I think that everybody experiences that overload. It’s one of those things … I don’t know if you’ve ever seen those descriptions of people that fortune tellers or astrologists use that everybody can identify with. There’s generic statements about, I often feel overwhelmed, but occasionally I’m very optimistic. Yeah, that’s me. And I think that if you start talking about meeting overload, that’s something that immediately everybody says, “Man, that’s my company,” because it’s just so pervasive. You’re rarely run into somebody that says, “No, not a problem here.”

Lisa Bodell: Well, it’s interesting. I used to say when I get off stage, people would … When I talk about this topic, it’s not like they address me as an expert. They hug me like a therapist, because they relate so much to it. It’s like, “You’ve seen my boss. You understand every meeting I’m in.” But again, what I reinforce to people is, here’s the good news.

Well, let me say it a different way. Here’s the bad news. You create it. You do this. Here’s the good news. You can change it. I don’t know a single manager that would look at you and say, “You know what? No, I want more email. Really? Can’t we keep the same level of meetings? They’re all so productive.” Nobody says that. The question really is, why do people feel that they can’t fix it? And I think this gets back to the topic of fear. If we can start addressing that honestly, as teams and as leaders … As leaders, we set the signal by ourselves. Reducing the friction, everyone else’s behaviors will be the same … Will follow, and they will also operate without fear. And it’ll start on very simple ways. It’ll be meetings. It’ll be emails. And all that crap will go away so they can focus on more meaningful things. The stuff they came to do at their job in the first place.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think meetings are a communication device, to a large degree, where people want to be sure that everybody’s on the same page and they don’t necessarily, as you say, trust people just to stay in their lane and get the job done. A while back, we had Paul Zach on the oxytocin guru, and he did some amazing research on trust in organizations. And he found that not only through surveys and observation but through blood samples, which is a unique approach to researching corporate behavior, they found that high performing organizations tended to be very high in trust. Not only as measured by their surveys, but even by oxytocin levels in the blood samples from employees. And then, he has a whole bunch of more specific recommendations for building trust.

But I think it comes back to what we’re seeing where, if you’ve got to have complex rules and procedures for everything, if you’ve got to have meetings to discuss everything, you are not only wasting time, but you’re also exhibiting distrust. And trust is one of those things that’s reciprocal. If I show that I trust you, you’re more likely to trust me. Where if I’m not trustful of you, then you’ll probably be distrustful of me to some degree. I think trust is a great, great lubricant. You work with different kinds of companies. Do small companies have complexity issues too?

Lisa Bodell: Yes, because it’s the human behavior. I mean, trust isn’t something that only … Mistrust isn’t something that only happens in big orgs. It’s a human, it’s a one on one, it’s a small team thing. My company, which is small … I have 17 people total. There’s complexity that pops up every time, and that’s because people get that human thing of, what if I make the wrong choice? What if I take a risk? What if the client will be mad? And so it crops up again and again. It’s a constant discussion. Small organizations have it less because they move faster and they don’t have the same level of scale and they don’t have the same level of rules. But the point is, that even small companies have it, so the more cognizant you can be of it before you start to grow, the better off you’ll be able to scale.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. And I think, too, that even though small companies may not have a lot of hierarchy and rules and procedures and so on that you see in bigger companies, they have other issues. Being an entrepreneur for years, I’ve certainly managed my share of smaller businesses, and I’m recalling one. We were doing our payroll. It was something that was not all that difficult to do. We just had to keep track of people’s hours and then fill out the proper forms and submit them properly and get the checks written from the bank and so on. Not a super complicated thing, but at the same time there was always this fear of making an error because that’s one thing you don’t want to mess up. You don’t want to overpay or underpay somebody, and you certainly don’t want to get your taxes wrong because then they’ll come after if you fail to get it in on time or … There are a lot of bad consequences if you screw up.

And we just took it for granted, that was part of the drill, and then ultimately we ended up outsourcing it to a payroll processing company and wow, it really simplified the internal operations. We had multiple things we no longer had to worry about that we had given away to an organization that actually knew what they were doing, and we’d insulated ourselves from the stress too of knowing exactly what the tax filing deadlines were and all those really important things that are the last thing a small business wants to deal with as a problem where suddenly you’re getting nasty letters telling you to appear in somebody’s office. I think even in those contexts, there are real opportunities for simplification.

Lisa Bodell: Yeah. We talk about an acronym called EOS, which is to eliminate, to outsource, or to streamline. That’s really the way to think about. If when you first look at something, the first goal should be to get rid of it. If you can’t get rid of it, outsource it, just like you said. Give it to an expert. Maybe your time can use some better way. You’re not stopping doing it, but your role changes. And the last one is to streamline it. Maybe the way you’re doing it isn’t efficient and we should question the way that we work. That might be a useful acronym for people that are listening, because you never know. You never know what opportunities to get some time back on things that matter could really improve life.

Roger Dooley: When you go into a company environment, what are some of the first things that you look at in terms of trying to gauge the complexity issues?

Lisa Bodell: Well, we typically do a diagnostic, and what we do is we ask them less than 10 questions. It takes them about five minutes to fill out, and we ask them, what do they spend their time doing? It’s a time value equation. Are you spending your time on valuable stuff or not? And it’s very revealing. How much of their time is spent on meetings and emails, reports, or other. Most of the time, the percentage of time that people spend on meetings and emails, they all report is like 170%. They’re not only multitasking, but their perception of how they’re spending their time is much more than 100% on just meetings and emails. It happens every time. It’s shocking.

And then we also talk about barriers. What holds you back from valuable things? How much is fear an equation? What’s your ability to get things done on a scale from 1 to 10? These types of questions, because what that gets at is, to be fair, the friction that is irritating them on a daily basis. That allows us to get at behaviors as well as quick wins, so we can go in immediately and surgically start to show change, because people at first will resist change. That’s just a human behavior. And if we can show them that it’s something within their control and it’s painless and there’s quick things they can do right away, that starts the momentum.

To share one of the easiest things that people can do and what we discover is, they just don’t question how work gets done. And so, the reason they can’t get things done is because they don’t even spend time understanding what isn’t getting done. We do an exercise with them called kill the stupid rule. And the best thing that comes out of that is, we say, “If you could get rid of any rule that would help you be more productive in your job on a daily basis, what would it be?” People come up with dozens and dozens of rules in less than 30 minutes, and those rules are within their control. They can all agree immediately to change them. And it starts this catharsis, this transformation with the … As you said, it’s like a lubricant that just gets the ball rolling and gives them permission to do it on an ongoing basis.

For people listening here, you can diagnose what the friction is. But if you want to get it started in a very simple way, in a good exercise, try killing stupid rules. Kill something and feel how it goes. It’ll start a good chain of events.

Roger Dooley: And one thing I recall … I forget if it is was in your book or somebody else’s, Lisa, but when people are talking about the rules that they were following, in one study at least it turned out many times there was not even a rule there. People assumed that it was a rule because everybody was doing it that way, or that’s the way it had always been done, and there no rule that specified that.

Lisa Bodell: And that gets too. If it’s not fear that’s driving people, it’s assumption, and they haven’t been taught that it’s okay to question assumptions. That’s one of the things we do is, we look at their work and we say, “Why do you assume that’s a rule? Why did you assume that this is how you have to do it?” And you can even do the five why’s to get to the root cause, but even having the discussion … That’s something people never have, and that’s where leaders can reduce the friction. They can allow for that discussion to happen.

Roger Dooley: How do these issues very internationally, Lisa … We think of the US as being a pretty fast-paced, business-oriented environment. How does complexity vary around the world?

Lisa Bodell: It doesn’t vary very much because we’re such a global society now and there’s multinationals, and these are ubiquitous technologies that people use. Meetings and emails aren’t things that just happen in more sophisticated societies, and they tend to, because of human nature, happen the same way. The nuance to be fair is in solving the problem. This is where you get into stereotypes. But what I have seen is, for example, when we do kill a stupid rule, it might be more difficult in some Eastern cultures than Western cultures to challenge people. And so, how you do it … It still should be something as a, what is okay? But how you go about killing rules might need to be done in a little bit more of a private hierarchy.

For example, we were doing a session in Japan, and the folks in Tokyo were there with a bunch of other groups from Asia and they said it would be particularly difficult for them to challenge or question assumptions in front of the boss. We had to facilitate discussions offline, not in groups, present the results in a different way. They got to the same end goal of killing some rules, but how it was facilitated had to be changed culturally.

Roger Dooley: I can see that. I know that in my experience, often in … Actually, both Asia and Europe, the hierarchy is much more pronounced. There is not quite the free flow back and forth between levels of the hierarchy. It’s more of a top down thing, which I could certainly imagine changes the way stuff has to done.

Lisa Bodell: Correct. Correct. Now, again, it’s still something that needs to be done and should be done. But it’s just understanding the how in that situation, and that’s fine. We just have to make sure that we’re cognizant of that and respectful of it.

Roger Dooley: I guess, maybe to inspire our listeners, Lisa. Do you have any success stories of organizations that reduced their complexity, and as a result prospered?

Lisa Bodell: Oh, my gosh. Yes. Many, in fact. We deal with a bunch of different organizations from Pfizer to Accenture to Novartis to … We’ve done it with Mark. We’ve done it with Google. And I mention those names because they’re regulated companies, and the reason that’s important for me to say is because regulated companies are usually the ones that say that they can’t do it because they’re regulated. And what we’re talking about is human behaviors.

I mean, we actually did a project, I’ll give you one specifically with EY, Ernst and Young. And we were in India, and during the session we killed stupid rules. And just one of the rules, one of dozens that were killed, the manager came up to us after and he said, “You realize just by giving me the permission to identify this rule, talking about it with my team, and killing it will save us over $100,000 this quarter.” And we were thrilled. It was one of those … They just hadn’t been given a method or permission to do it. Think about it. If just one epiphany like that had saved that much money, how much more could that happen in other people’s companies?

And by the way, it’s not just that $100,000 money example. It’s time. The benchmark for success shouldn’t be just money saved. It should be time saved. It can be ability to get things done. It can be morale. It can be increased visibility external. There’s lots of ways to measure it beyond just dollars.

Roger Dooley: I’m assuming that management buy in to this process is important. What’s your experience been in the best way to get that done, for instance, if you’ve got somebody who is at a lower level of the organization who can see the need for changes, for reduction in complexity, but at the same time doesn’t have the authority to necessarily change things totally on their own. How does one go about getting management to buy into this?

Lisa Bodell: Let me give you the good news. It’s not hard, because usually managers will see it as an efficiency play. Simplicity in their mind is about efficiency. It’s about taking waste out of the system. It can be, frankly, if you’re junior, how you position it, because I don’t know any boss that would say, “No, no, no. Keep the waste in the system.” In fact, they’re begging people to take waste out of the system. You could look like a rockstar. But positioning it could be important.

The bigger thing to me in the more advanced leaders are the ones that you don’t have to convince because they know … They love to hear that somebody’s group took the initiative, and they decided within their own sphere of control … They didn’t go out of their swim lane. That they have a practice of killing stupid rules. They become the mavericks, the role models, and leaders embrace it more and roll it out on a bigger scale typically. If you have a boss that you experience friction with and resistance, position it as an efficiency play taking waste out of the system. If you have a boss where you’re just looking to impress, or frankly make a difference which is the goal, talk about wanting to kill a stupid rule on your own and suggest it as something they can across the organization. That bigger leader will look like a rockstar and they will thank you for it.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think your positioning advice is spot on, Lisa, because if you approach a manager about changing the way things are done, if that manager has been perhaps the one responsible for creating or approving those processes, there might be some pushback there. Nobody likes to be told that their idea, something that they were in favor of is wrong. But by attacking it obliquely and saying, “Hey, we can find a way to get some waste out of the system to reduce cost, increase profits, that would answer the why.” As you say, it’s pretty hard to disagree with that.

Lisa Bodell: Pretty hard to disagree. And the other thing too is, because of course it’s not meant to be an ego stroke, but, “Hey, we want to keep this. We love this idea. We even want to make it more effective.” That’s one way to position that. Nobody likes if their process or their project gets killed, but some things unfortunately are not worth their time.

Another thing you can do if people resist getting rid of something is, this doesn’t have to be black and white. You don’t have to kill it. You can pilot getting rid of it. For example, we had an experience with McGraw Hill where they wanted to get rid of the … People hated the monthly operating report. It’s the thing where people … Lighters were going off in the room like a concert when people suggested getting rid of this thing, and the leader in charge was the one who had created this report and wasn’t too willing to get rid of this report.

And so, what they agreed upon was, “No, no, no. Good report. Understand the need for it, but let’s do this.” There might be other reports that are covering some of this stuff and we want to be able to help you make your numbers, Paul, which was the name. Why don’t we pilot getting rid of it for three months? And if you still feel like you get the data you need from other sources, let’s agree to kill it. But if not, let’s bring it back. Paul agreed. After three months, they killed the report. It’s also taking the fear, as we started talking about earlier, out of the killing to make it a little bit safer for people. It can be baby steps.

Roger Dooley: Great. That’s really great advice, Lisa, and probably a good place to wrap up. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking to Lisa Bodell, author of Kill the Company and Why Simple Wins. Lisa, where can our listeners find you and your content online?

Lisa Bodell: First, you can go to FutureThink.com. That’s T-H-I-N-K. FutureThink.com. And you can find a whole bunch of resources there, either eliminating complexity or being able to invent innovation. You can also go on Amazon, check out the books and the tool kits that come with it, and just contact us. We’re happy to come in and share more of these tips and tricks with some of our workshops.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to all those places and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Lisa, thanks so much for being on the show.

Lisa Bodell: Okay. Thank you, Roger. Was a pleasure.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book Friction is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.