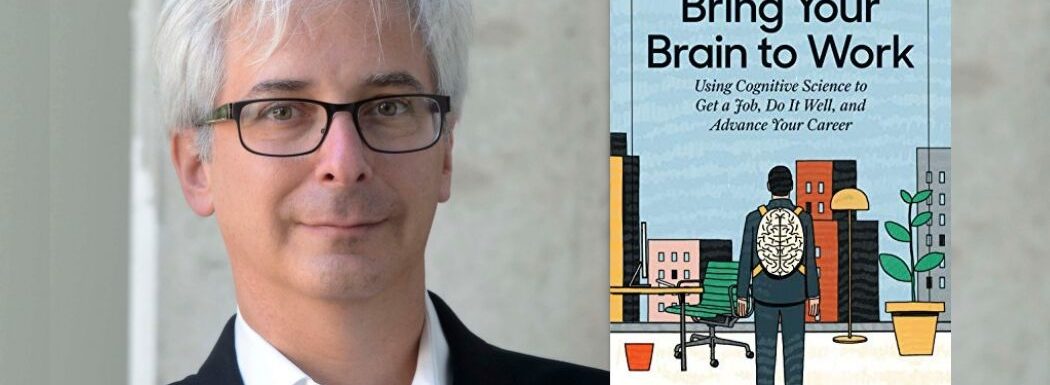

Art Markman is the Annabel Irion Worsham Centennial Professor of Psychology and Marketing at the University of Texas at Austin, as well as Executive Director of the IC2 Institute. The author of over 150 scholarly papers on topics such as reasoning, decision making, and motivation, Art has also written several books, including Smart Thinking, Smart Change, and Brain Briefs.

In this episode, he shares insights from his upcoming book, Bring Your Brain to Work, and discusses what it takes to interview like a pro. Listen in to learn how to improvise in an interview situation, what you can do to become more productive, and more.

Learn how to become more productive and interview like a pro with @abmarkman, author of BRING YOUR BRAIN TO WORK. #interviews #careers #self-improvement Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Tips for acing interviews.

- Why it’s crucial to go into an interview prepared.

- What IC2 is and what they do.

- How Art is reaching broader audiences.

- His take on “finding your passion.”

- What it means if a company gives you the Myers-Briggs personality test as part of the hiring process.

- How to become more productive.

Key Resources for Art Markman:

- Connect with Art Markman: Website | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | LinkedIn

- IC2 Institute

- Amazon: Bring Your Brain To Work

- Kindle: Bring Your Brain To Work

- Amazon: Friction

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr. Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. Today’s guest is a threepeat visitor to the show. Doctor Art Markman is Professor of Psychology and Marketing at the University of Texas at Austin right here in my own home town, and Executive Director of the IC2 institute. He’s written over 150 papers on topics including reasoning, decision making and motivation. Art writes at Psychology Today and Fast Company, and co hosts the radio show podcast Two Guys On Your Head. He’s the author of Smart Thinking, Smart Change, Bring Briefs, and the new book, Bring Your Brain to Work: Using Cognitive to Get a Job, Do It Well, and Advance Your Career. Welcome back to the show, Art.

Art Markman: Roger, it is always fun to talk to you.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So, Art, since you were last on the show, you’ve had at least one change in your bio. You used to be head of the HDO at UT, human dimension of organizations. Now you’re head of IC2 Institute. What’s that?

Art Markman: Yeah. The HDO program was a new venture. We spent eight years creating a program that was designed to use the humanities and the social and behavioral sciences to help people in business understand people, but I’m kind of entrepreneurial in spirit, and so after eight years of working on that and having it go from an idea that a lot of us thought was going to be fun to work on to a thing, I realized I was probably reaching the end of my useful time in the director’s role there, and so I started looking for something else to do. The IC² Institute at UT, actually it’s about a 40 year old think tank that looks at entrepreneurship and innovation, and historically actually played a pretty significant role in helping Austin to go from being a sleepy college town in the 1970s to being the Austin, Texas that makes all of the lists that you see today.

Roger Dooley: Right. So, you are the enemy of Keep Austin Weird. Austin is no longer as weird as it used to be.

Art Markman: Well, remember, Keep Austin Weird is the motto of the Chamber of Commerce. We’re not really the enemy of that, we’re just the enemy of the people who believe in Keep Austin Weird. So, yeah, I think so, but actually the institute itself I think played a big role in that transformation, but what we’re trying to do is to think about what are the new big problems in trying to help regions to do economic development. We’re actually focusing ourselves on rural areas and small isolated cities where the models that helped a place like Austin to become Austin are probably not going to be successful. It’s a lot of fun and it gets me meeting a lot of new people and there’s a lot of human centered kinds of problems there that need to be explored, and so I’m really looking forward to what I can do there. I’ve been there since decision of 2018, so really just started out.

Roger Dooley: Great. Thanks for correcting me on the IC². That should be a super script, I guess.

Art Markman: Yeah. It’s hard to type that out in text. I guess you could put a little carrot.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. But it’s great that the university is so involved in the community. I spent a lot of years in South Bend, Indiana, home of Notre Dame, which is a great university. But there seem to be substantially less spill over to the community from the school. Students would graduate and catch the first plane out of town all too often, unlike Silicon Valley is the total counter example where students go to Stanford and go down the street and work on Sand Hill Road or one of the many other great places there. So, it’s great that UT does that. So, Art, your new book has the term cognitive science in the name. It’s a phrase that we hear but not all that much. Explain what cognitive science encompasses.

Art Markman: Yeah. I’m actually a native born cognitive scientist. My undergraduate degree is in cognitive science. Really what cognitive science is is an interdisciplinary study of the mind. A lot of times when we think about the mind, we start thinking about psychology or perhaps neuroscience, but what cognitive science recognizes is that there’s a variety of approaches you need to take if you’re really going to understand the way that people behave and why. You have to know some psychology and you want to understand the brain so you want to have some neuroscience, but it’s useful to have some computation to understand computers and to understand how you might program intelligence. It’s also useful to have a little bit of anthropology to understand the cultural influences that help to program people’s behavior, as well as to understand linguistics, to understand how language functions and permits you to communicate. So, when you take this variety of different perspectives, you realize that you can actually create an understanding that’s greater than the sum of the parts by adopting all these different perspectives.

Roger Dooley: It’s really a term I think that probably deserves more use and respect. I know I sometimes struggle with my own personal branding because I began writing about neuro marketing, which had kind of a neuroscience emphasis, but pretty soon found that that was just sort of a small piece of the pie and that I got much more involved in the social sciences, behavioral science research and so on, and also recognized that these aren’t mutually exclusive disciplines. You know? It’s not like neuroscience is telling you one thing and behavioral science is telling you another thing. Often they’re just giving sort of different perspectives and a deeper understanding of the same thing. So, it’s very interesting. Maybe I might start adopting that a little bit. Actually, neuro marketing has the same sort of branding issue because there are people who wanted to restrict that term to, “Well, if you are going to be studying ads using EEG or FMRI, okay, that’s neuro marketing, but other stuff isn’t.” I’ve always argues for a much broader approach to it, but if you can improve your marketing through your understanding of how the brain works, regardless of how you get that, then it’s a good thing.

Art Markman: Yeah, yeah. Some of these boundaries seem a little artificial to me in the end.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So, Art, back in my business school days, long, long ago, I took an organizational psychology class, org psych as we called it, and that was all geared around managers. How do you motivate people? Maslow’s hierarchy and probably some Freud and stuff. Those are the old days. Yeah, we’ve come a long way since then, but I think even then there was a pretty good recognition that businesses are full of people who may not actually behave like logical, rational robots going back to the Taylor days and scientific management and all that, but it seems that even for many years after I was doing that, organizations never really acknowledged it. I mean, they may have given some lip service to it, but their management practices were pretty much assuming that folks behaved in a logical way, that if you want people to sell something, you put a bonus in there for it and so on. Lately I’ve been seeing some businesses set up behavioral science units. I’m wondering what you make of that since you’re pretty close to that sort of intersection of academia and industry. Is this a legit trend now?

Art Markman: Yeah, I think it absolutely is. Certainly I’ve spent a lot of time in my transition from only writing papers that get read by 30 of my closest colleagues to trying to write for broader audiences, I’ve certainly found myself spending a lot more time with people in companies trying to help them to bring more of this cognitive science into the way that they do business. Some companies are importing it through people like me, and many of them are now setting up their own units and bringing that expertise in house so that they have people who are dedicated to really studying that.

I think it’s crucial, both for understanding internal processes, how to motivate employees, how to make people feel valued, but also for external purposes, to understand the behavior of clients and customers and to understand how to understand their needs better and to meet those needs more effectively.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So, moving onto your book, Art, Bring Your Brain to Work is sort of the opposite perspective. Rather than being written primarily for managers and leaders and HR directors and such, it’s really written from the individual’s point of view. In fact, when we’re recording this, we’re kind of approaching graduation time for, well, both transitioning from high school to college and from college, perhaps, into the real world or other studies. One of the books that people are commonly gifted then is Dr. Suess, The Places You’ll Go, which is kind of a fun book, but to me, your book is a much more practical gift. Not so many cartoons in it, but something that would actually be really useful for an individual making that kind of a transition. First of all, I applaud your perspective on that. Who is it actually written for?

Art Markman: Yeah. I had several audiences in mind. Certainly as somebody who liked college so much that I never left, I certainly had college students in mind for this because I’m around a lot of students who really don’t quite know how to translate whatever it is that they’ve learned, even if they’re in a major where they think there’s a direct translation from their major to the workplace, let alone students in the liberal arts who have learned a lot of skills that will be valuable in the workplace, but may not quite understand that translation. I think the book is valuable for them, but I actually think it’s valuable for anyone who’s really contemplating whether their career has actually led to the kind of contribution that they were hoping to make.

I feel like I always like to say that almost everybody I know has a mind and almost nobody knows how their mind works. I feel like if people understood more about the way that their minds functioned, they would do the things that they do better. They would align their work a little bit more effectively to their underlying values, they would do a better job of presenting themselves to other people because they would understand how the things that they put forward are being evaluated, and they would do a better job of motivating themselves. I certainly think graduates are one group, but I think that there’s just a lot of people out there who are not 100% satisfied with their careers who might be looking for a different perspective on how to think about what might make a career fulfilling that would benefit from this.

Roger Dooley: It’s great. Now, you’ve made a key point there too, Art, that it’s not just focused on the fact that you’ll be dealing with humans who you need to understand how humans work, which isn’t always logical, but also to understand how you yourself work. That’s something that often gets overlooked. What are the common pieces of advice that you hear really pretty much given to anyone from students to folks who are already along in their careers as to find your passion or pursue your passion. Really ironically, a few hours ago I was recording a podcast on someone else’s show and they asked me for a piece of common wisdom that I disagreed with. I said follow your passion, pointing out that there’s certainly nothing wrong with following your passion, but if you are expecting to follow your passion and earn a living, you may want to do a little bit of research along those lines too, because your passion may not necessarily pay the bills. When I saw the section of your book, Find Your Passion, it immediately made me chuckle. What’s your take on the passion thing?

Art Markman: Yeah. I think there’s a couple of pieces to it, one of which is that actually we can learn to love all kinds of things. What it is that we happen to love right now has as much to do with what we’ve been exposed to so far in our lives as anything else. Part of the problem is there’s a whole wide world out there that many of us are unfamiliar with. Certainly, if I had had to pick my major before I went to college, I would never have chosen cognitive science because I had never heard of it. You know? I was lucky enough to be at a university where I got to choose my major in my sophomore year and was able to discover several things that I was more interested in. I think that we all have to be open to the prospect that we’re going to continue to stumble on things that are fascinating to us, and that frankly, if the work that we do ends up having a benefit to the world and to really attach itself to something meaningful and to something bigger than ourselves, often we can discover that that’s something that we end up becoming passionate about, even if early on we didn’t realize that this was something we were going to like.

Roger Dooley: You know, I think that often in college, I know looking at my own personal career, Art, in education, I started off in chemical engineering as an undergrad because I had an interest in chemistry and it seemed like one of the more interesting professions. I knew I pretty much wanted to be either in engineering or science, but partway through… I was at Carnegie Mellon, which in those days was one of the few places that had an actual computer science department with a bunch of real computers which were monstrous things that filled rooms, but I got really interested in that. My advisor at the time was a chemical engineering department advisor, assured me that computers were just a fad and that there would always be a need for chemical engineers.

Ironically enough, I ended up in that digital world, although decades later really. It was a little bit of seeing that that was something that was really interesting for me because I was… while I was sometimes deserting my classwork and not doing homework, but instead I’d be over at the computer science center running programs, that should have been a clue that if you’re doing this for fun and the other stuff seems like a drag, maybe you should pursue your passion a little bit. There might have even been a pretty good way to earn a living there in that particular case. But I ended up there by a circuitous route eventually. You’re right, you really don’t know. It’s unfortunate that so many universities obligate you to make a choice even before you show up on campus, in many cases.

Art Markman: The University of Texas is one of them. I actually say in the book that while I love the University of Texas, one of my great frustrations is that we actually force our students to declare their major before they get onto campus. Frankly, not only are there university pressures, but there are parental pressures as well. A college education is an expensive thing, it’s a big investment, and parents who may or may not be helping their students to pay for the university education are justifiably worried about what career is going to lie ahead for students, so they often put pressure on our students too to pick and major, and particularly to pick a major where it seems obvious how you’re going to make a living.

I think that we have to recognize that we’re in an era in which being productive in the modern workplace is going to require a tremendous amount of ability to adapt. One of the things that I say early on in the book is that most of the problems that you have to solve in the workplace in order to succeed, you never took a class to help you to solve those problems, some of which are interpersonal issues and some of which are just how do I navigate a changing workplace that is different from whatever curriculum that I took in school could have possibly prepared me for.

Roger Dooley: Well, and something that regardless of what you major in that you probably haven’t been prepared for is just dealing with the human issues in the workplace. I’m sure there are some universities that offer a course or two that might somehow equip people, but I would say 99.9% of college students graduate without any real training in how to get into the workforce, how to cope once you’re there and so on.

Art Markman: That’s right.

Roger Dooley: With all those human issues. But one of the first things I guess that either a new grad or actually even folks that have been in the workforce for awhile are likely to encounter is the dreaded interview. The research I’ve seen on interviews shows that they’re not very good predictors of job success. Even people who think they’re great interviewers and they can really pick winners often overestimate their capabilities. But nevertheless, most companies still use the interview process. What are your suggestions for the interviewee?

Art Markman: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. Part of the problem is it’s a version of the law of small numbers. Right? The more observations we can get on anything, the better we can learn about it. Yet, a lot if the information that gives us a long term view of somebody gets less attention than the interview, which is this very small sample of behavior. Unfortunately, it is a very important piece of the process. But when you go into an interview, I think there’s a few things that are important. One of which is obviously you’ve got to be prepared. There’s no substitute for learning as much as you can about the company that you’re going to be interviewing with to really understand who are they, what are they doing, what have they been doing lately, to look on there’s a lot of information these days on the internet about what it’s like to work in places. You would like to walk into that interview having really done your homework, because that will pay off in several ways, including just people noticing that you’ve done your homework, that you are the kind of person who makes sure that you step into a situation completely prepared.

There’s a bunch of boxes I have in the book that I call jazz brain boxes. I talk about the motivational brain, the social brain, the cognitive brain, and the bonus brain of the book is the jazz brain, which is your ability to improvise. One of the things I point out really early on is that in order to improvise successfully, you actually have to have a lot of knowledge. Your ability to improvise in an interview is going to mean coming in over prepared, and that’s one big thing. I think the other that’s really important is to remember that the interview is actually a two way street. We often think of the interview as I’ve really got to impress this recruiter, this hiring manager, this interviewer, because they are the gatekeeper. What I forget to do is to really learn about the firm in the process of that interview. When I go into that interview, they’re telling me a lot about who they are. If they throw out a lot of wacky, off the wall questions, then they’re telling me that what they care about is my ability to deal with sudden change.

If I get to a question where I’m not sure what to do, if you start asking a lot of questions in return and trying to do joint problem solving with my interviewer to the extent that they respond to that, what they’re teaching me is that they are a company that believes that it is my potential and my ability to work together that is going to matter rather than my ability to have an answer at the ready. So, I really want to learn as much as I can about the company and it’s culture in the process of going through that interview.

Roger Dooley: I’ve got a great example of a misplaced question. When I ran an IT outsourcing company, we had placed an ad for RPG programmers, which was, even then, a legacy programming language used by IBMAS400 computers, which probably one or two of those still on the planet but not very many. But got an applicant, and the applicant looked better for more of a PC tech opening that we had, so we brought him in for an interview. Partway through, the interview wasn’t going all that well from my perspective anyway, but then he finally answered the big question, “So, what kind of role playing games do you code here, anyway?” “Okay, we weren’t looking for that kind of RPG,” but clearly somebody who had not done his homework.

I think the psychology of interviewing is such that interviewers tend to favor people who speak well, present well, are more sociable and so on, even if they are being hired for, say, some kind of a developer position, those skills may not be as important as their ability to write code. But what you say about being prepared makes a lot of sense because even if that preparation isn’t directly reflective of your skills for the job, it will have that halo effect of making you seem more with it, brighter and so on, that will impress the interviewer. Makes a huge amount of sense.

Art Markman: Yeah, yeah. No, I think you definitely want to over prepare for that. I think it’s just so important. That halo effect matters a lot. I think people don’t recognize that that initial impression influences how people interpret everything else that you say, because everything in the world is a little ambiguous. Right? Is that person brash, confident or arrogant?

Roger Dooley: Right, yeah.

Art Markman: It could be the very same behavior. So, if you’re positively included towards somebody, you think, “Wow, that person is really confident.” But if you started off with a negative interaction, now you think, “Well, that person is just arrogant. I wouldn’t want to work with them.”

Roger Dooley: Definitely the case. There’s so much research on how lasting first impressions are and how hard they are to overcome, even when presented with evidence to the contrary that the first impression is wrong, they still tend to be kind of sticky. One thing that hasn’t changed since I was first looking for a job and today is that the companies still often rely on psychological tests to evaluate employees. What’s your take on stuff like Myers Briggs?

Art Markman: Well, I’m going to separate this into two pieces. I think that there’s a lot of valuable psychological testing that one could do. None of that involves the Myers Briggs. The Myers Briggs, everyone I know who is involved in the science of psychology seems to be on a career mission to try to stamp out the Myers Briggs despite the fact that it doesn’t seem to want to go away. The Myers Briggs was developed in 1940s by some people with no real background in psychology who thought Carl Jung was really cool. I too think Carl Jung is really cool, but I don’t think he’s the basis for a system of personality characteristics. The literature would bare me out on that. There are very few studies that demonstrate consistent reliable effects of the Myers Briggs classifications. So, if a company gives you the Myers Briggs as part of the process of hiring you, what they’re telling you is they want to dress themselves up in a veneer of data and science, but they don’t actually know the data or the science.

Now, using something like the big five personality characteristics or another valid instrument, that’s a whole other ball game. I do think that there’s value in understanding people’s personalities, although at the same time, I think it’s important to recognize that people’s personality characteristics aren’t destiny. You may be relatively on the extroverted versus introverted side of things, but just because you’re an introvert, doesn’t mean you can’t possibly get up in front of a group and perform effectively. It just means you’re not going to love it. So, we gave to recognize that personality characteristics tell us a little about you, but you still need to understand how motivated somebody is to be willing to perform in a particular circumstance.

Roger Dooley: What do you think accounts for the popularity of Myers Briggs? I even see people putting on their social profiles, “I’m an INTJ or something.” You know?

Art Markman: LSMFT.

Roger Dooley: Why is that? It seems to be that people, not just companies using it, but even individuals seem to accept those characterizations.

Art Markman: Yeah. You know, well, I think they accept the characterizations because they’re kind of like horoscopes. If you think about judging versus perceiving, I can squint and go, “Yeah, I definitely am perceptive.” So, I think that people can see elements of themselves that confirm whatever diagnosis they got. One of the fundamental problems of the Myers Briggs is that if you look at the basic personality characteristics, so the big five personality characteristics or the scientifically validated version of the Myers Briggs. These are things like openness and agreeableness and conscientiousness. Extroversion and neuroticism actually are the other two. One of the things we know about those characteristics is that if you look at the distribution of those characteristics in the population, it’s a well behaved distribution, meaning it looks a little bit like a bell curve centered around the middle, which means most of us have elements of both the poles of the dimensions that have been created, whereas the Myers Briggs forces you to classify people so that you get that four letter code in the end. The problem is chances are you’re actually more in the middle than the test makes you appear to be, and so you may actually misrepresent yourself as being more extreme than you actually are in ways that I think are unhelpful.

Roger Dooley: Well, I think all consultants need to have a four quadrant system. You know? Boston Consulting Group made millions from their classifying businesses as cash cows and stars and dogs and so on. That, in some ways-

Art Markman: Planners need SWAT analysis, absolutely.

Roger Dooley: Right. You’ve got to have that. I think for your next book, Art, you need a magic quadrant of some kind.

Art Markman: That’s been my problem.

Roger Dooley: Let’s talk a little bit about productivity. That’s something that affects all of us, whether we’re new to the workforce or whether we’ve been there for awhile, what are your tips based on cognitive science for us to be more productive?

Art Markman: Yeah, I think there’s several elements. One of them, of course, is just we need to get to know our own attentional style a little bit better. We live in a world right now in which the office environment can be quite distracting. The half height cubicle is the bane of human existence. It’s full of all kinds of distraction. Some people deal with that just fine. I mean, there are people who’s attentional styles can be laser focused on whatever they’re doing at the moment and don’t notice that there’s somebody prairie dogging in the cubicle next to them, but then there are people who get disrupted by a cricket chirping 12 blocks away, and those folks are really going to need to find a strategy for overcoming a lot of those distractions, potentially doing some amount of their work in a more closed off space, despite the fact that these open office environments were designed to create a certain amount of engagement with people, they tend to just be lower productivity.

Roger Dooley: I just saw some studies that showed that there was potentially less interaction with peers in open offices apparently because people sort of close themselves off. They put their noise canceling headphones on and they don’t look up from their screen for fear of being distracted, and so you actually get less engagement with your peers.

Art Markman: Yeah, plus you hate all your colleagues because they’re annoying you because they’re always in your face. Yeah, no, that’s absolutely right.

Roger Dooley: Although the online interaction goes up, so you do see more slack messages and IMs and such, but it’s really kind of ironic that the supposed benefit, other than low cost, proved not to be the case.

Art Markman: Yeah, no, I think that’s right. It’s unfortunate that people went ahead and did all of this office design work without really any data to speak of. I think from a productivity standpoint, I think another thing that’s really important is people need to spend a lot of time developing really good processes for doing their work. I think that we’re in an environment that has a lot of distractions, and it’s not just physical distractions but emails and texts and slack messages and everything else. We have to find clever ways of creating blocks of time to get our work done. We need to do a better job of removing some of the defaults that drive our behavior. For example, most people end up scheduling meetings with other people for an hour because that’s the default on most calender programs despite the fact that most meetings don’t require an hour. I think we can do a much better job of really being strategic about the way we use our time and not allowing ourselves to be driven by whatever is in front of us at the moment.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. There’s even… you’re looking at it from the individual standpoint, but from the organizational standpoint too. In my book Friction I talk about some of the things organizations have tried to do to address some of those factors like limiting the size of meetings, so you can’t schedule a meeting with more than X number of people, even though the software might allow it, but they fixed the software so it won’t allow it or the default meeting timer blocking out certain times so there are only certain day or days or times of day where you can schedule meetings. Also eliminating… this one, it would be my personal favorite because it’s so simple, eliminating those horrible distribution lists where by typing in four characters you can send an email to everybody in the department or four different letters to everybody in the entire company. By making it that easy for people to do, sometimes people are going to do that. You’ve got to make that impossible to do.

Art Markman: That’s right. We are inherently lazy creatures.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, hey, that’s probably a pretty good place to wrap up. Let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Art Markman, Professor of Psychology and Marketing at the University of Texas in Austin, and author of the new book Bring Your Brain to Work. Art, how can people find you and your ideas?

Art Markman: Yeah, lots of different places. If you want more information about all of my books, including Bring Your Brain to Work, the best place to go for that would be my website, smartthinkingbook.com. There are tabs for all the various books there. In addition to that, I love to just give away as much knowledge as I can to people. As you mentioned upfront, I blog pretty regularly for places like Fast Company and for Psychology Today, as well as having a radio show and podcast. You can find out information about all of that on Twitter. I’m @abmarkman. I also have an alter page on Facebook and I’m on LinkedIn and just love to connect with people, so feel free to find me on any and all of those places and I post links to all the stuff I’m writing.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Art, thanks for being on the show. We always learn a lot from you.

Art Markman: Well, thanks so much, Roger. I’d be remiss if I didn’t say good luck with your new book, which I’m sure your listeners know all about. But there’s a great community of writers out there, and I’m happy to be associated with many of them, including you.

Roger Dooley: Thanks, Art.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book Friction is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to rogerdooley.com/friction.