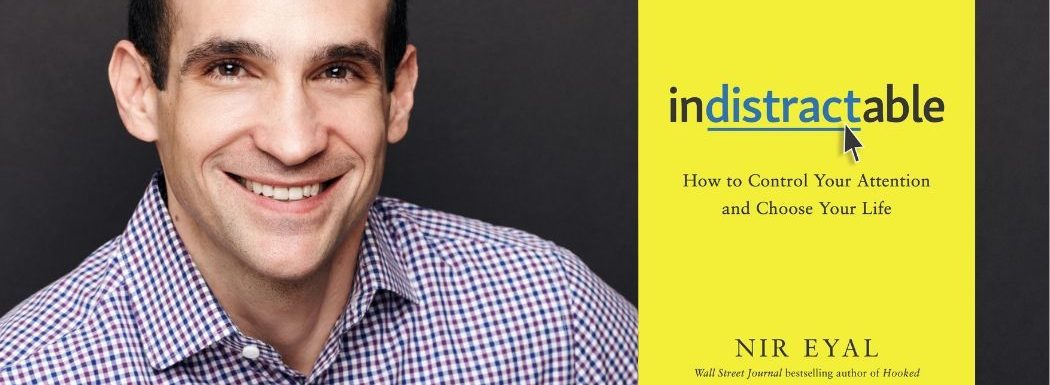

Nir Eyal is a writer, consultant, and teacher on the intersection of psychology, technology, and business. Dubbed “The Prophet of Habit-Forming Technology” by The M.I.T. Technology Review, Nir has founded two tech companies and his writing has been featured in The Harvard Business Review, TechCrunch, and Psychology Today. He is also the author of the bestselling book, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, as well as Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life.

In this episode, Nir explains how to reduce distractions and be as productive as you want to be in your day. Listen in to learn how to address the internal triggers that cause your distraction and channel them into helpful acts of traction so you can make the most of your time.

Learn how to overcome distractions and get the most out of your day with @nireyal, author of INDISTRACTABLE and HOOKED. #distraction #attention #flow Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why we don’t do the things we know we should do.

- How to address the fundamental reason you get distracted.

- The depth of the problem of distraction today.

- What really drives our behavior.

- The opposite of distraction.

- How to channel your internal triggers into helpful acts of traction.

Key Resources for Nir Eyal:

- Connect with Nir Eyal: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn | Facebook | Instagram

- Indistractable.com

- Amazon: Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr. Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m your host, Roger Dooley. Today’s guest is an old friend making his third, I think that’s a record, appearance here. Nir Eyal is a successful entrepreneur and the bestselling author of Hooked, by far the best known guide to building habit forming products. Something I learned just today was that Satya Nadella, the CEO of Microsoft, is supposed to have held up a copy of Hooked and urged all of his employees to read it. That’s a real endorsement. If you haven’t read it and you work on any kind of product or service, don’t wait any longer. You’ll get great insights into how to onboard customers, produce an experience that keeps them with you and doesn’t drive them to your competitors.

Today, though, there’s a dark side to some of those wildly successful digital products. Some have engineered those products to both demand attention of users and keep them engaged for more time than is really beneficial for those users. Many people think we’re in a distraction crisis. Instead of doing productive work or enjoying friends and family, we’re glued to our phone screens looking at cat videos or being outraged by the antiques of politicians. As Nir will tell, you the problem goes beyond your smartphone and other digital devices.

Nir joins us today to offer an antidote to engineered distraction and an alternative to a distractive life. His new book is Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life. The very person that reverse-engineered products to determine why some became habits and others didn’t is here today to tell you how to regain control. Indistractable isn’t a theoretical treatise. It’s packed with not just science-based insights but anecdotes, a schedule template, a distraction tracker, and even a book club discussion guide.

Nir, welcome to the show.

Nir Eyal: Thanks. It’s so great to be back for the third time. I’m the record holder here. Very excited.

Roger Dooley: Indeed. Indeed. It could be in jeopardy. We’ve got a couple other two timers, but you are the man right now.

Nir Eyal: Excellent. I’m honored.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Nir, how big a problem is distraction today?

Nir Eyal: Well, I think you can look at the studies and you can riddle off all kinds of facts and figures about this problem. But I think we all kind of see what a problem this is. Although I will say once in a while, I’ll meet somebody who says, “No, I don’t struggle with distraction.” I mean, it’s rare, but I do find the occasional person. But if you’re the kind of person who does everything they want to do every day and you’re not distracted, then this might not be the podcast episode for you or the book for you. But if you’re like me or at least like I was, I found that I’d have the best of intentions and the knowledge. Right? That I know what needs to get done every day and yet somehow I wouldn’t do it.

I know I need to exercise. I know I need to eat right. I know I need to focus on my work and do that big project that I’ve been procrastinating on. I know I need to be fully present with the people I love like my daughter and my wife. Yet I wasn’t doing what I know I needed to do. Why? I mean, that to me is such a fascinating question. It’s also not a new question. It’s something that Socrates and Aristotle had talked about 2,500 years ago. They called it akrasia, this tendency that we have to do things against our better judgment. I just thought that was such an interesting question to explore because while the problem is not new, our tools have definitely changed. They are new. Right? Social media and email and group chat. These are tools that we haven’t quite figured out how to adapt our behavior to. Sometimes we find that they can get the best of us and be tools if not the source of many of our distractions.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. TV was damaging enough, but that wasn’t really weaponized the same way that some of these apps are. I think that probably just about everybody has experienced those days where you had a plan to start the day. You had one or two or three things you intended to accomplish. But of course, you get to the end of the day and realize that you’ve barely made any progress even though you are super busy. Now, I think people sometimes treat that as just a time management problem as if there’s a simple thing. Well, if you just created that to-do list and ignored everything else, then you’d get it done. Which is kind of like saying, “Well, you would be the appropriate weight if you just didn’t eat bad foods and only ate the good stuff.” It’s really easy to say but pretty hard to do.

Nir Eyal: Right. I think part of the problem, by the way, you’ve hit around it here, is that this myth of the to-do list as I call it, is that… I think that a lot of us think that what we read in productivity books that tells us, “Well, just put everything on a to-do list and it’s out of your brain and it’s on a list and it’ll magically get done.” But of course, that’s not true. A to-do list is a list of outputs. It has nothing to do with the inputs. Right? You wouldn’t go ask a baker and you’d say, “Look, I need a hundred loaves of bread.” Then he magically makes them appear. No. A baker has to figure out the inputs, the flour, the factory, the workers, the yeast. All the things that go into making bread needs to be accounted for.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. He’s got to get up at two in the morning to get the ovens too.

Nir Eyal: Yeah, exactly. It’s not just about the output. There’s an analog here for knowledge workers that as knowledge workers, our output is what’s on our to-do list. But we don’t plan for the input. Two thirds of Americans don’t keep a calendar. That means that, look, if you leave your day open and you don’t plan your day, somebody else will. This is why I say we can’t call something a distraction unless we know what it distracted us from. This is one of four techniques in this model that help us get a grip on distraction to finally help us do what it is we say we’re going to do. That’s the big idea behind this book. Is not just around technology. These are just the latest tools. But big picture, what’s the deeper psychology around why, despite knowing what to do, why don’t we do the things we know we should?

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. I have to ask you, Nir, is it true that you bought a 1990s Word processor to try and increase your focus on your writing?

Nir Eyal: I did. I did. I did that because that’s what all the books tell you to do. Right? I read every book on this topic. I didn’t intend to first write the book. I had a problem in my own life that I found that I was distracted more than I’d want. When I was with my daughter, I was distracted. When I was with my friends, I was distracted. When I try and do my work and write, I was distracted. I really wanted to get to the bottom of why. Why don’t I do what I know I should?

I read these books on digital detoxes and these 30 day plans. I did what they told me to do. I got rid of the technology. It didn’t work. I bought the flip phone. I bought the Word processor from the 1990s. You know what? Not only did I suffer professionally for it because, look, I’m an author. In this day and age, authors need to be online. They need to connect with fans. They need to be part of the discussion. I enjoy that stuff. It’s part of my livelihood. Just swearing off this technology is pretty unrealistic for a lot of people. But then furthermore, I found that I would sit down to write and I say, “Okay, no technology. Just this 1990s Word processor without an internet connection. Finally, I can focus. No social media. No apps. No email. I’ll get to doing what I’m going to do. But, you see, there’s this book on the bookcase that I’ve been meaning to read. I should probably check that out for a minute.” Or, “Let me just organize my desk for a quick sec.” Or, “You know what? The trash. The trash needs to be taken out.”

I would still get distracted because I hadn’t dealt with the real source of distraction.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think our brains seek that out. I actually had a technique which has nothing to do with the content in your book, I don’t think, although you may find that it does. But back when I was in business school, I had to do a lot of reading much of it, which was incredibly boring. Or assignments, especially business law where they use the type of method where you have to read 50 pages of a judge’s ruling on a case to learn what somebody could have summarized in one paragraph as to why the judge found what he did. But in any case, I would do exactly what you suggested. I would find a book that I really would not normally sit down and read. Something like Vanity Fair by Thackeray, which is not a really engaging read as things go.

But I would use that as a break. I would distract myself from even more boring legal reasoning by reading that. Actually get through some classics that way even though it wasn’t really serving me the original purpose of what I was supposed to be doing.

Nir Eyal: Right. Right. I think it actually brings us to this really important first step in becoming indistractable. The first step is to master the internal triggers. Just to back up a minute, one of the things I don’t think I appreciated when I first started reading this or writing this book was how important it is to understand the real source of distraction. That we like to blame what I call the proximate cause. The tool in our hands, the phone, the Facebook, the email, whatever it might be. The tool that we’re using as opposed to getting to the root causes.

As you exemplified through the story, yeah, the root cause was a bad feeling. It was boredom. Right? Fatigue, uncertainty, loneliness. These are the things that drive our behaviors. This is really important to understand that in fact, all of our behavior… We used to believe Freud’s pleasure principle. That everything we do is about the desire for pleasure and the avoidance of pain. Turns out that’s not really true. Neurologically speaking, it’s actually pain all the way down.

Once we understand that even, in fact, when people say, “Well, what about something that feels good? Don’t people do things because it feels good?” Well, not exactly. In fact, even the pursuit of something pleasurable is psychologically destabilizing. Wanting, craving, desire. There’s a reason we say love hurts because those sensations, the way the brain gets us to do something is by making us crave. By making us uncomfortable enough to do something about it even if it’s for the expectation of pleasure. Remember, the brain doesn’t do what feels good. The brain does what felt good. Those memories create these uncomfortable associations to go strive and get that thing that felt good in the past that we learned in association with.

That means if all behavior is prompted by a desire to escape discomfort, that means that time management is pain management. That’s the fundamental first step, is to master these internal triggers. If we don’t do that, we’re always going to get distracted from something. I don’t care what the latest life hacks and productivity tricks are. If you don’t address the fundamental reason why you are doing something against your better interest by getting distracted, you’ll always find something to distract you.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. I think that’s a really good point, Nir. What I was experiencing, and I continue to have not quite as formal as the incident that I described or the practice that I described of substituting one kind of somewhat boring reading for an even more onerous kind of reading. But I know that if I’ve got a task that is for some reason something I really don’t want to do, it’s kind of amorphous or it’s a big job or I’m not quite sure where to begin, that’s the moment that I choose to do some other tasks that is somehow perceived as being beneficial for business. But it might even be as simple as, “I wonder if I need to reply to anybody an email or on Twitter or whatever.” Simply because that sort of blank screen and amorphous task ahead of me are not something that I want to wrestle with.

Nir Eyal: Right. Right. I would argue… I hate to be the bearer of bad news. But I would argue that that is actually just as much of a distraction. The reason you’re doing it is very clear. The reason you’re doing the less bad thing is because you’re avoiding discomfort. You’re looking for the least uncomfortable route. Right?

Roger Dooley: It’s totally a distraction because what I’m supposed to be working on that moment is that unpleasant, amorphous task that I don’t want to do. So I say, “Well, I can justify this because it’s a G. It’s good for business or whatever.” It can be a way to force you to do a task you didn’t want to do that is slightly less onerous, I found. But you never get the really bad one done.

Nir Eyal: Exactly. Exactly. If you have a big goal like, “Oh, I need to write a book.” Or, “I need to work on that report.” Or, “I need to work on a presentation,” that never gets done. I would argue, in order to understand distraction, we have to understand what distraction is not. What’s the opposite of distraction? The opposite of distraction is not focus. The opposite of distraction is traction. Traction and distraction both end in the same word. They both end in action, A-C-T-I-O-N. Reminding us that these are things that happen to us, not things that… I’m sorry, things that we do, not things that happen to us. These are actions that we take. Both words, by the way, came from the same Latin root, trahere, which means to pull. Traction is any action that you take that pulls you towards what you want, things that you’re doing with intent.

Distraction is the opposite. Anything that you do, that pulls you away from what you really want to do, things that you want to do with intent. I would argue that as opposed to just looking at the easy-to-blame distractions: television, social media, and video games, I would argue that checking your email when you plan to work on that big project or doing whatever it is that we do to waste time and we’re not even… I call this pseudo work. It’s not really a waste of time, it’s just not what you plan to do with your time. I would argue that that is equally pernicious. That even if it’s, “Oh, it kind of feels like work. I’m just going to check this one thing or do this kind of work, any task,” that if that’s not what you set to do with your time, that is just as much of a distraction. It’s the opposite of what you planned to do with your time.

Roger Dooley: Right. In my book, Friction, that you’re familiar with, Nir, I talk about a lady that worked for me at one point as a product manager. She was really not making good progress on those core product management activities. That would be innovating new products, finding creative solutions, and so on. But she was in 30 plus hours of meetings per week. I said, “No wonder. You can’t really expect to do any deep work or creative work if three quarters of your workweek is meetings. Plus, you’ve got some other stuff in between there like email and phone calls and so on.” I think that was the same sort of distraction that you’re talking about.

She never managed to pull herself out of those meetings and say, “Gee, no. I just can’t do this. It’s not important for me. I can’t get my job done if I go to this meeting.” Because it was a somehow more attractive work-like thing that, “Hey, I’m part of this. They’re talking about my product, so I should be here and so on.” That, in the moment, seemed like a good use of time. But in aggregate, it was a distraction and prevented her from getting the real work done.

Nir Eyal: Yeah. There’s a whole chapter in my book about meetings. Because again, the book is not just about tech distractions. It’s not just about the devices in our hands. Distraction is all around us. The open floor plan office, I have a chapter about that. How to prevent distraction from your colleagues. Email. Meetings are a huge source of distraction as you described with your friend’s story. I mean, how much time do we waste every day on pointless meetings? Part of what we have to do is to ask ourselves, “Why do we keep calling these senseless meetings?” Part of it has to do with internal triggers. That when people feel a low sense of agency and control in their organization, well, they start feeling these internal triggers. We know that there’s a confluence of two factors that literally drive us crazy at work.

This is the research of Stansfield and Candy. They’ve found that the confluence of high expectations and low control, those type of work environments that have those two factors, high expectations, low control, these type of work environments literally drive us crazy. They lead to anxiety and depression disorders. What do people do when they feel the symptoms of anxiety and depression disorder? They feel bad. Those internal triggers spark them to do things that are distractions. What do they do? They send emails that didn’t need to get sent. They participate in Slack channels and group chat channels that waste our time. Or they call meetings to hear themselves think. Why? Because that helps us feel in control. It gives us agency when we are lacking it. We have to understand the root causes, not only of why we do these strange behaviors in the workplace, but also learn how to mediate some of these pernicious behaviors.

I give people tactics, for example, borrowing a little bit from your philosophy here around friction, adding friction around meetings. One thing that they do at Amazon is you can’t just call a meeting. You can’t just say, “Hey, I want to meet to talk about this.” No, no. You can’t do that. You have to come prepared with an agenda and a briefing document. That adds just enough friction to weed out the meetings that people call for the sake of hearing themselves talk. Or when they don’t actually want to do the real work. Kind of like you said, you’d read the less painful book. Sometimes people will say, “Okay, a meeting, that’s worky. That feels like work.” No. You know what you need to do to do your job? Sit at your desk and do the hard work. Think of the answer. Do the research and come up with a conclusion. Having a briefing doc, having an agenda or no meeting is one way to add friction to make sure that we can get rid of some of these superfluous meetings.

Roger Dooley: Right. It wouldn’t surprise me too that creating that briefing document actually results in a solution occasionally. I don’t know if you’ve ever had that experience here, but I’ve had some kind of a tech problem. Computer software. Then I’ve tried researching and can’t figure it out. I start composing an email to tech support or creating a forum post if that’s the venue. About halfway through that as I’m describing what I tried, it suddenly occurs to me, “Hey, there’s something I didn’t try.” Lo and behold, that’s the solution. Forcing me to think through it in a semi-coherent fashion because I’m trying to write down what I did and what I need to do, that alone is enough to trigger the solution. That’s a brilliant strategy. Of course, any time you force people to fill out a form or write stuff down, that adds a little bit of friction to put to a process. Which it can be a good thing at times.

Nir Eyal: Absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah. There are definitely techniques around reducing distraction, hacking back the external triggers when it comes to meetings, when it comes to our colleagues and the open floor plan office. I mean, that turned out… I thought that people would complain most about their devices distracting them, but you wouldn’t believe how many people told me about how just working in an open floor plan office, how much distraction that leads to. It’s everywhere and it’s not going away. It saves companies tons of money not having to give everyone a full office with a door to close.

That’s actually where I took some inspiration from a group of nurses at UCSF where it shocked me to hear this, but the third leading cause of death in the United States of America, if it was a disease, the third leading cause of death… Number one cause of death by the way is heart disease. Number two is cancer. The third leading cause of death would be prescription mistakes. Believe it or not, 200,000 Americans are harmed every year when healthcare practitioners give them the wrong medication or the wrong dosage of medication. Hospitals across the country just think this is a fact of life. Nothing they can do about it. But this is a 100% preventable human error.

A group of nurses at UCSF decided to study this problem. They found that the source of the problem was distraction. That nurses, while they were dosing out medication, were being distracted with a tap on the shoulder from a colleague in the middle of their medication rounds and they were making mistakes. Now, what’s interesting is that they didn’t realize that the mistakes were happening until something terrible happened later on. This is exactly what happens to us knowledge workers. Right? We don’t appreciate how much better our performance could be if we weren’t constantly distracted. We don’t realize the mistakes until it’s too late.

What did the nurses do? They actually finished the study after they concluded the source was distraction. They did something really phenomenal. They figured out a way to reduce prescription mistakes by 88%. They almost eliminated the problem. The solution was plastic vests. These plastic vests that nurses would wear that told their colleagues not to disturb them. That they were busy with medication rounds. Those plastic vests had a tremendous impact, 88%. It’s unbelievable.

What do we learn from this? How can we apply this to the office worker, the knowledge worker? Well, every copy of Indistractible, the print edition, comes with… Or you can download this if you get the audio edition or the ebook edition. There’s a screen sign, a card stock sign. A piece of card stock that you can pull out of the book. You fold it into thirds and you put it on your computer monitor. This says on it… It’s a big red sign. It has a stop light on it that says, “I’m indistractible. Please come back later.” It’s a way to signal to your colleagues, “Hey, not right now. Okay? This is my focused work time. Please come back later.” It’s incredibly effective.

I know people say, “Oh, that’s what I wear my headphones for.” But people don’t know if you’re just listening to a video or a podcast or what you’re doing. Or if you’re interruptible, we need to send a more explicit message to tell colleagues, “Nope, not right now.” I’m doing my indistractible work time.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. That’s really great, Nir. I love that. I know that my own experience with that. I fortunately haven’t been in really an open office plan often. But even when I was in a somewhat private office, but there were people around. Like people outside the door and answering phone calls, and the usual things that go on in an office. I switched from that to a home office environment. It was so funny because I think the… On one of the first days I was working in my home office where it’s basically nobody, no distractions, nothing, I started working at, I don’t know, 8:30 or something. I woke up around 11:30 and realized that I had been working pretty much in a flow state for that whole time. It was such a novel experience because I had not had that same experience when I was working in an office, even though as offices go, it wasn’t bad at all. I mean, it wasn’t like people were walking in front of my face constantly. But just the background activity and noise was a big difference.

Nir Eyal: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Absolutely. Absolutely. Yeah, certainly.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. We think of things like fitness trackers as being useful and not particularly habit forming. I guess there’s actually some evidence that shows that fitness trackers don’t really always get us more fit. But our mutual friend, Zoe Chance, at Yale did a TED talk on her fitness tracker experience and how… Well, I want you to tell that story.

Nir Eyal: Sure, yeah. I talk about this story in the context of internal triggers. I try and make the case that it’s not about the behavior itself, it’s about what it displaces. Zoe Chance is this brilliant woman who teaches. Now, she teaches at Yale. She’s in our field of behavioral design and consumer psychology. She taught a class a few years ago where she tried out different products and she wanted to show examples of how various products can shape our behavior. She brought into the class the strive pedometer. In the course of doing a tear down of this product and understanding how it works and how it changes human behavior, she found that she got hooked herself. This pedometer would start out as a healthy habit of 10,000 steps per day devolved into a bad habit where she was doing 20,000, 30,000 steps a day.

In fact, one evening, she got a notification on her phone that said, “Hey, guess what? If you walk 20 stairs, we will give you triple points.” She said, “Oh, wow. Triple points. Great. I’ll do it.” At midnight she decided to go down the steps of her basement and back up and earn those triple points. When she got back to the top of the stairs, the app rung out again and said, “Hey, great job. If you do it again, we’ll give you another trip points.” She continued going up and down the stairs to her basement until two in the morning. At two in the morning, she got herself out of her days and realized that she had walked more steps than it takes to get to the top of the Empire State building. In that moment, she was distracted.

Is walking healthy? Of course it is. Is exercise a good thing? Yes. Unless it’s being done as a distraction. Now, what do I mean by that? We talked about how the difference between traction and distraction… Traction is anything that pulls you towards what you want to do, things that you do with intent. Distraction, the opposite, is anything that pulls you away from what you do. Now, in that moment, walking which seems like a healthy thing, that’s physical exercise, was a distraction just like checking email when you want to work on that big project or reading one book when you really should have been reading the other. These were distractions because that’s not what she wanted to do with intent. What she wanted to do with intent was to go to bed and get some rest at two in the morning. Yet she was walking up and down her stairs.

The reason goes much deeper than just the pedometer. In fact, I would claim that blaming your pedometer for your distraction is just as shortsighted as blaming our phones for distraction. Now, what I didn’t tell you about the story is that during this time period, Zoe Chance was going through some really tough circumstances. She was going through a breakup with her husband. She was also looking for a full-time teaching position, which hadn’t come through yet. She was under a lot of stress, a lot of internal triggers. What she was doing to escape those internal triggers was going deeper and deeper into using and obsessing over her strive pedometer.

I make this point of how we can become unhealthfully dependent on some of these devices. I chose a specific example of pedometer to try and destroy this moral hierarchy of, “Oh, this is good and this is bad.” No, no. Anything you do with intent is traction. If it’s consistent with your values and that’s what you want to do with your time, do it. Enjoy Netflix. Enjoy Facebook. Enjoy a video game if that’s what you want to do with intent. But know the difference. Don’t use these devices on the app makers’ schedule. Use it on your schedule when it’s consistent with your values. If you are getting distracted, realize the underlying cause. What are you escaping? What uncomfortable psychological emotion are you looking to escape from when you use these products and services?

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Now, I realized we can’t really get into every listener’s individual issues. But when if they find themselves in that situation where there’s a behavior that they’re being distracted, but there is a root cause of some other kind, how do you begin to address that? I suppose recognizing what that might be is the beginning. Any other tips?

Nir Eyal: Yeah. There’s two things that we can do when it comes to these internal triggers. We can either learn techniques to cope with the discomfort, or we can fix the source of the problem. Okay? Now, I think recently, maybe the pendulum has swung too much into the realm of just learning to cope. Techniques like meditation. I’m all for meditation. It’s great. I didn’t write about it in the book. In fact, I have a sentence in the book where I say, “I will not talk about meditation anymore.” Not that it doesn’t work, but because it’s been addressed already ad nauseum. That’s a technique that we can use to cope with discomfort in a healthier manner. But look, sometimes, we want to actually fix the problem. If we can fix the problem, we should.

When it comes to, for example, in the workplace. We talked about earlier how distraction at work is a symptom of cultural dysfunction. Sometimes the source of that dysfunction, the source of why we feel these internal triggers, is something that we can address. We can change that corporate culture. I talked about it in the book about BCG, a company that I used to work for as my first job after college. They had a very tough culture where people were constantly connected to their devices. Back in those days, it was BlackBerries, not iPhones, but we were constantly connected to our devices for fear. For fear that we might miss something all the time.

Well, that’s not a healthy work environment. Distraction really is a symptom of cultural dysfunction. We can change those things, but we can’t change everything. Sometimes, part of being a human being is just the ennui of life. We need to learn tactics around how we can cope with that discomfort. There’s a few tactics. One, we can reimagine the trigger. Two, we can reimagine the task. Three, we can reimagine our temperament. We can use these techniques in coordination to help us make sure that we channel those internal triggers into helpful acts of traction as opposed to leading us towards distraction.

Roger Dooley: You mentioned BlackBerry. One thing that either I didn’t realize or if I knew it, I forgot it was that they are apparently the inventor of the ping notification for a new email. This is the amusing part. At the time, that was viewed as being really a stress reducer and a time saver. I guess that went horribly wrong.

Nir Eyal: Right. Because the idea was, well, you didn’t to check your phone all the time. All right? We’ll tell you when to check your phone with the ping, with a notification. Of course, this conditioned people to use their device not only when they heard the ding, but when they were feeling these internal triggers of stress, uncertainty, boredom. They would check their devices all the time. This is called an external trigger. Out of everything in the book, a lot of critics out there will say that technology is the problem. Technology is the problem. I actually think fixing the technology problem is the easiest part. I can tell you in about an hour how to make your phone indistractible, how to turn your phone into a device that will not distract you anymore. Look, two thirds of people with a smartphone never change the notification settings.

Is that crazy? Is it me or is that just nuts? Two thirds of people never change their notification settings. We can’t really complain about technology distracting us if we haven’t taken just a few minutes to change those notifications settings and turn off the ones that don’t deserve to interrupt us when we’re working, when we’re with our family, when we’re with our friends. That’s almost the easiest part, but there are eight different environments that I go through including group chat, meetings, open floor plan offices, the desktop, email. All of these different environments where external triggers can prompt us to do something we later regret.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I agree, Nir, that the internal triggers are the tough ones because I have turned off just about all notifications on my devices other than certain kinds of emails that are flagged as important. They’re very, very few of those that come in. That does not prevent me, though, from mindlessly jumping onto Twitter or Facebook or LinkedIn or Instagram or email to see if I’m missing anything. Fixing the external stuff is important, but getting to the internal stuff is probably more important and more powerful.

Nir Eyal: The good news is you don’t have to give it up. I used to do this all day long. Right? Check email, check Instagram, check the social channels all day long. Then I started beating myself up because I would moralize it and say, “No, I shouldn’t. I shouldn’t. I shouldn’t.” That just made the problem worse. We know that rumination around the shouldn’ts can actually really make the problem worse. There’s this study around smoking that shows how rumination could in fact be one of the main factors around addiction. Is that we constantly tell ourselves, “Don’t. Don’t. Don’t. Don’t. Don’t. Don’t. Don’t. Okay, fine. I will.” It’s almost like pulling on a rubber band. When you let it go, it not only goes back to center point, it goes and deflects further. That feeling of finally relieving our self-generated discomfort is a major source of why people get addicted in the first place.

The idea is not abstinence. The idea is to learn how to get the best of these tools without letting them get the best of us. How do we do that? We turn distraction into traction. On my calendar every night is time for social media. I want to check Twitter. I want to be on YouTube. I want to check Facebook. They’re great. They’re wonderful tools. I mean, our connection was, in many part, started and facilitated through these wonderful tools. We don’t need to banish them from our lives and abolish them from our existence. Instead, we need to just use them on our schedule. To make time for them. To say, “Yep, I’m going to be on social media. Here’s that time in my day so I don’t have to constantly use it all day long.”

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, that’s great advice. We could go on and on, but that’s probably a good place to wrap up. But let me remind our listeners that today, we are speaking with Nir Eyal, bestselling author of Hooked and the new book, Indistractible: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life. Unless you are one of the few people who has attained perfect focus and an ideal life balance, you need this book. Nir, where can people find you and your ideas?

Nir Eyal: Yeah. Thanks, Roger. My website is nirandfar.com. Nir spelled like my first name, N-I-R, and far. For more information about Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your Life, you can go to indistractable.com. There are all kinds of tools and resources there including an 80-page workbook that’s free. All at indistractable.com. It’s indistractable.com.

Roger Dooley: Awesome. Well, we will link to those places, to your books, Nir, and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll put a text version of our conversation there too. Nir, thanks for being on the show and best of luck with the book.

Nir Eyal: My pleasure. Thanks so much, Roger. Third time.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book Friction is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to rogerdooley.com/friction.