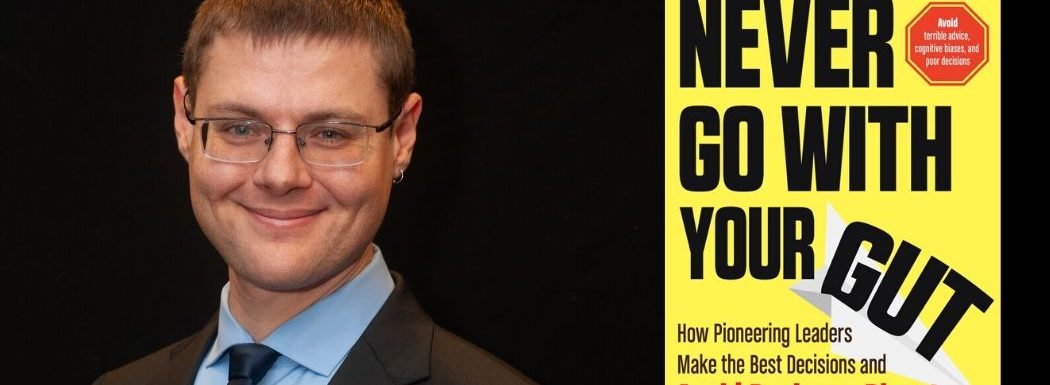

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky is CEO of Disaster Avoidance Experts, and has spent over two decades consulting, coaching, and training hundreds of clients across the world. With over 15 years in academia—including seven as a professor at Ohio State University—he has published dozens of peer-reviewed papers in academic journals like Behavior and Social Issues and the Journal of Social and Political Psychology. His thought leadership is also featured in Fast Company, CBS News, and Time.

In this episode, Gleb shares insights from his recent book, Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make The Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters, such as how to seize opportunities and avoid serious problems in your business. Listen in to learn why you shouldn’t always trust your gut, why it’s important to plan for both success and failure, and more.

Learn how to seize opportunities and avoid serious problems in your business with @Gleb_Tsipursky, author of NEVER GO WITH YOUR GUT. #intuition #leadership Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to seize opportunities in your business.

- Why you shouldn’t always trust your gut.

- How to avoid serious problems in your business.

- Why you should plan for success and failure.

- The importance of planning for problems.

Key Resources for Gleb Tsipursky:

- Connect with Gleb Tsipursky: Website | Twitter

- Amazon: Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make The Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters

- Kindle: Never Go With Your Gut

- Audiobook: Never Go With Your Gut

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

- Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley.Before we get to our guest, I want to share some exciting news. My new book Friction was named one of the best business books of 2019 by Strategy Plus Business Magazine and one of the three best management books. If you haven’t picked up your copy yet, you can find it on Amazon, most bookstores, or go to rogerdooley.com/friction for more information. And now for our regularly scheduled program, our guest this week is Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. He’s a Cognitive Neuroscientist and expert on behavioral economics and decision-making. He’s also the CEO of Disaster Avoidance Experts, and has worked with clients around the world including Aflac, IBM, Honda, Wells Fargo, and the World Wildlife Fund. He’s also spent 15 years in academia, including seven as a Professor at Ohio State University, or perhaps I should say The Ohio State University. Gleb is the author of the bestselling The Truth-Seekers Handbook, and his new book is Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. Welcome to the show, Gleb.Gleb Tsipursky: Thank you so much, Roger, and congratulations on your book being named the best strategy book. That’s really exciting.Roger Dooley: Well, thank you. Yeah, I was excited. It sort of came out of the blue, so it made me really happy.Gleb Tsipursky: Oh, that’s always great.Roger Dooley: Gleb, let’s get started with a simple question. What does a disaster avoidance expert do?

Gleb Tsipursky: Great question. We typically think of disaster management where somebody jumps into the middle of a crisis and manages it, and that person is a hero. Well, lots of times that person is the one who led to the crisis and has to be there to recover from the crisis. And that person looks around, and we think about turnaround CEOs and so on, but really the best profit, the most profit comes from preventing the disaster in the first place. When you look at a bunch of studies, they’ll tell you that you get 20 times as much resources from preventing disasters than actually managing them.

There’s a good Ben Franklin quote about this. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” He knew this way back when the American Revolution. So that’s what I do. I help folks prevent disasters. Looking ahead, looking at the future, seeing what’s going to happen that’s a big problem for them, or missing an opportunity which can be just as disastrous as having a serious problem, and help them make sure that they seize their opportunities, and make sure that they avoid serious problems for the sake of their bottom line.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I’m curious, Gleb, you make the point that sometimes the leader who is responsible for stopping a disaster is the one that created. Typically you think of a turnaround expert as somebody who comes in after the original leader’s been chucked out because of the problem, but are there some leaders who thrive on disaster, who maybe take some really risky courses of action so that if they do work, great, if they don’t work, then well, they can be the hero and save the company?

Gleb Tsipursky: Absolutely. Look at Elon Musk. He’s a typical, prototypical example of a very reckless leader who takes bet the company risks, which sometimes don’t work out. I mean, he often, often, often over-promises and under-delivers, but people still follow him, partially because he is glorious, he takes risks, and he does deliver sometimes, which is why he is worth several billion, but he also runs into many, many, many problems. Tesla’s come close to bankruptcy many times. It’s one of the reasons why it’s the favorite short stock betting of people who think that Tesla will eventually go bankrupt. And looking at the whole situation, I’m not a financial expert, I’m not an expert on Tesla, but I would have to say that I think one time in the future, Elon Musk’s luck will run out when he makes another bet the company bet. He’s a typical example of someone who revels in managing disasters, and someone who may well be chucked out at some time.

Roger Dooley: Hmm. Interesting. The book is about how to avoid making critical mistakes in business. But one of my business heroes, Jack Welch, who’s the legendary CEO of GE that you actually referred to in the book, he wrote a book titled From the Gut. Malcolm Gladwell has sold millions of copies of Blink, which sort of suggests that intuition is often better than really detailed analysis. If you have to make an important business decision and your intuition is telling you something, why should you not trust it?

Gleb Tsipursky: Well, our intuition is not adapted for the modern environment, and Jack Welch made a number of bad decisions when he was going with his gut in terms of some mergers, and he failed in his effort to do the merger with Honeywell. His chosen successor has led GE into a serious, serious, serious problem. I mean, we see that GE’s not that far from being bankrupt right now, and that has resulted from decisions that were made during Jack Welch’s time. He is not nearly as glorious a leader as he is presented often. So that’s with Jack Welch. Malcolm Gladwell and many other… I mean, you think about Malcolm Gladwell, you think about Tony Robbins, lots of people tell you to go from your gut, these business gurus and some business leaders, and you know what? They do that partially because it’s where the money is. It’s very comforting to tell people to do what they want to do anyway.

Now, unfortunately, we are not evolved for the current business environment. Our gut instincts, our gut reactions are about from the Savannah environment. That’s what they feel comfortable with. We feel comfortable with fight or flight responses, immediate in the moment responses, and we overreact to threats and underreact to opportunities, and that causes us really big problems when we’re making decisions. We can go into a number of examples, but let’s take an example right now of WeWork. Now, WeWork was a company that was valued about $75 billion six months ago. Huge company valued at $75 billion, and in the last round of evaluation when it was going for its public IPO, it ended up being valued at $7 billion. $7 billion. That’s an order of magnitude loss. That’s about $70 billion loss, $68 billion, because they went for an IPO at the wrong time with the wrong governance structure.

Adam Neumann, its leader, went with his gut on going with the IPO and resulted in a serious business disaster. That’s one example. Another example comes from-

Roger Dooley: Right, he’s an example of a leader that did get chucked out, and now they’ve got new leadership that is in save the company mode.

Gleb Tsipursky: Save the company mode, and quite possibly… I mean, the last article I saw earlier today was that they’ll be laying off a third of its workforce, which shows that it was some really bad decision-making went into the hiring spree. Now, another leadership situation may or may not be chucked out is Boeing. Boeing has made some really bad decisions with the 737 Max. They have decided to go have the leadership of Boeing with producing 737 Max despite many, many engineers at Boeing telling the leadership that, “Hey, 737 Max is not really ready for production.” Why is that? Well, the problem with Boeing is that they have a great safety record and that can be dangerous in itself when you fall into what’s called the normalcy bias.

The normalcy bias is one of these dangerous judgment errors that I talk about in my book. We have over a hundred dangerous judgment errors, cognitive biases, that cause us to make terrible decisions, and I talk about the 30 most dangerous ones in the book Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters and how to address them. Normalcy bias is where we assume that nothing seriously bad will happen. Things will go according to plan. Things will go like they are. Boeing will keep its safety record. The leadership just couldn’t imagine that something as bad as the kind of 737 Max disasters would happen, and that’s why they went ahead with the production when they really shouldn’t have, as we see now. And so we see what happened in the Boeing leadership may well be out eventually as a result of this very serious mistake.

Roger Dooley: Hmm. Yeah. Well, I think our listeners are very familiar with the cognitive biases. We’ve had articles on the Neuromarketing website about how to marketers can use these cognitive biases to be more effective with their messaging to customers. Not to say that you’re trying to hack your customer’s brain, but people do make decisions in a way that is not always rational, and if you don’t understand that and try to appeal to them in purely rational terms, you’ll fail. But what are some other cognitive biases that mislead us as decision-makers?

Gleb Tsipursky: One of the most prominent ones, that is planning fallacy. And this one, a lot of people run into it, a lot of marketers run into it, a lot of business leaders run into it. It’s one where we tend to assume that our plans will turn out to be perfect. They will be great, and that’s why we’ll make strategic plans and we think that they will not fail, and we just put our resources all into these strategic plans. It’s like the old saying, “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” And probably folks heard that saying. They make plans. They think everything will go well. That’s a very misleading saying, just like go with your gut is a very misleading saying. Both of those are not things you should do. You should not go with your gut and you should not have the idea that failing to plan is planning to fail.

Why is that? Because we assume that our plans will go correct, and then we don’t anticipate problems. A much, much better saying is planning to fail for problems is failing to plan. Again, planning to fail for problems is planning to fail. I’ll give you an example. I was working with a client who I was doing training for Vistage, which is a group, CEO peer advisory group. And one of the people there when I was doing the training, I was talking to them about the kind of marketing leader in his company, and I was talking about how we tend to make plans that are perfect and they often go wrong. And he acknowledged that this is something that happens regularly in his company.

When they think that a marketing campaign will take $2 million, it regularly takes more. Takes $3 million or more, because things come up that they don’t anticipate. The people, they thought they did sufficient market research, and they actually didn’t do sufficient market research when they did the initial marketing campaign, and the marketing campaign didn’t work out nearly as well as they wanted, so they needed to put additional resources into it. When they looked again at the plan, like why did they screw up, they saw that they didn’t do sufficient marketing research on the market and the people who would buy the product. That’s a typical example that marketers make where they think their plans will turn out well and they don’t, and they don’t account for problems.

Roger Dooley: Well, it seems like we always tend to sort of plan for perfection. We just assume that, “Okay, we’re going to spend this much. This stuff is going to happen. It’s going to take this long.” And anybody who’s been remotely associated with software development knows that things never happen in the time that people expect they will, because things always take longer. And I think it was von Clausewitz, I do not recall the exact quote, but it says something like, “The best strategy never survives the first encounter with the enemy,” or something like that. And so really, you have to look at contingency plans. You’ve got to figure out what can go wrong. And I guess that’s probably an essential part of disaster planning is really sort of hammering away at the assumptions that underlie anything, and trying to figure out what could go wrong.

Gleb Tsipursky: That’s exactly right, Roger. That’s one aspect of disaster planning. How can you address the problems? The other thing that people don’t plan for, and it’s very surprising to me that they don’t plan for, is not planning for success. And that is another big problem, because let’s say your marketing effort works out more better than you planned. What are you going to do then? If you’re not ready for it, if you haven’t planned for success, what are you going to do? And this was a situation where I worked with another company, a financial services company that was actually marketing a new insurance product. And it worked out quite better than they planned, and they got many more orders, orders that they couldn’t fulfill. And so that was a serious problem for them that they didn’t anticipate the success that would come and they weren’t prepared for it. And so that’s another type of thing that often fails for companies.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. I think that most of our listeners are familiar with Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking. System 1 being fast, intuitive and rule-based, and mostly non-conscious, System 2 more analytical and rational and conscious. Common sense, our brains don’t like to be in System 2 and will default to System 1 whenever they can, and I guess this is part of the problem with decision-making, right? That we tend to not want to do that hard analytical thinking and instead go with our gut.

Gleb Tsipursky: That’s right. Kahneman is actually part of the older wave of scholars who discovered all of these problems, and he’s right now sort of outmoded by the new wave of scholars. I’m a cognitive neuroscientist myself. I study this topic as well as being a consultant, coach, and trainer who trains companies, leaders on this topic. What we found with recent research is that he is too skeptical about our ability to be effectively with System 2. The best strategy is not simply to say, “We should be cold, unemotional, stay in System 2.” That’s not the right strategy. The right strategy is to use our system, to use our intentional system to develop healthy mental habits, change our System 1. We can do it.

I mean, think about it this way. You’ve learned to drive a car. Think about the first time you were learning to drive a car. It was very hard to do. I remember learning that. I failed my first car driving test. One things I found so hard to do was to pump the brakes when I was doing the driving test, to say just me. But I didn’t have anti-lock brakes on my car, and that was pretty common for cars at that time. And so I didn’t pass the driving test, because part of the driving test involved pumping the brakes instead of slamming on the brakes.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, even more recently, about I guess 10 years ago, I got a car that had a much smaller than today’s rear view cameras or displays, but there were the two normal side view mirrors and the rear view mirror in the center of the windshield, but there was also a little tiny video display there of a backup camera. And adapting to that was like learning how to back up again, because the image was not reversed and it was just like there were stuff going on in there. There were lines in there showing where the back of the car would end up. And until you learn that, suddenly it was like I could barely back up competently. Even though I’ve been driving for decades, suddenly it was like you had to relearn again.

Gleb Tsipursky: There you go. And that’s a perfect example where we now, we tend to think that we drive on autopilot. It’s very comfortable. That’s because we taught our System 1 how to drive on autopilot, so it’s a learned mental habit. It’s a healthy mental habit that we had to learn. I mean, the listeners probably learned to very quickly tell apart spam emails from good emails or marketing calls from calls that you want to focus on. You probably learned how to delegate tasks effectively and organize your work. All of those things feel automatic. They feel like we’re an autopilot, but it’s not really. You’re not really going with your gut reactions at that point. You’re going with how you learn mental habits. This is the key to addressing what Kahneman and Tversky and others found, that first wave of scholars.

And what they didn’t focus on, what I and other scholars focused on, is how do we solve this? We solved the cognitive biases by developing healthy mental habits that specifically and correctly address each of the cognitive biases that we deal with. And that’s what my book is about, Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. What kind of mental habits, what kind of strategies can we take to relatively easily and simply deal with cognitive biases?

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think beyond that sort of proactive thinking about cognitive biases, it seems too that there is an experience factor in business leaders and decision-making. I mean, I’ve thought about this not nearly as deeply as you have, Gleb, but thought about this for years. And what I really saw happen was experienced leaders develop sort of a brain firmware that enables them to go sometimes into a situation and immediately start making decisions that are more or less automatic or intuitive or experience-based without a lot of analysis. Somebody who’s turned around five struggling car dealerships can go into a sixth one and probably immediately start saying, “Okay, this got to change. That’s got to change,” without really deeply thinking about at least some of those issues. But at the same time, that doesn’t always work if somebody has been experienced in one industry and then goes into another industry.

Gleb Tsipursky: Yeah, and that’s exactly has to do with these mental habits. What the research shows is that this person, a leader, develops certain effective mental habits which work, because they’ve known that in this specific context and this specific setting, they work really well. The problem with these business leaders is they tend to be over-confident. Then this is one of the worst, worst, worst cognitive biases, this overconfidence. The older business leaders, more experienced ones tend to be more over-confident than younger leaders, than younger people, so they often actually make more mistakes than younger people. And this is a problem for older business leaders, older marketers. Basically, they don’t notice how the context around them changes when they go into a different situation, and they use the same methods of decision-making as though they’re in their old situations. They tend to be over-confident.

An example, a lot of business leaders make huge mistakes when they do things that they’re not familiar with like mergers and acquisitions. We see research on mergers and acquisitions showing that about 80 percent of mergers and acquisitions fail. They fail to create new value for companies. They destroy value. 80 percent. That is a huge rate, but mergers and acquisitions are increasing. Why is that? Because business leaders go into mergers and acquisitions thinking that, “Hey, I am good, I’m confident, I made a lot of money, therefore I’ll do this new thing, and I will use the same methods as I did before.” And they just don’t really do the kind of due diligence and analysis that they need to. There are specific things.

I’ll give you an example. I was working with one manufacturing company that was buying another one, the leadership was buying another one, and what they were doing, they looked at the external aspects of the company and said, “Hey, this company looks good. It matches our products. Let’s go ahead and buy it.” And what I asked them to do is look. We often, too often just look at the external financials, look at the due diligence, look at the products. You don’t look at the internal products and systems, the processes and systems, and the internal culture. How will those mesh? And once they started investigating the internal culture there, they found that the culture of the company they wanted to buy was pretty toxic and really opposed to their own.

It was much more hierarchical. It was much more domineering. Whereas the culture that they were coming in with was much more of open and team-based, and the processes and systems were aligned with that kind of domineering culture versus the team-based processes and systems. It would have been so much more effortful for them to actually merge than they originally thought. So as a result, they rethought this decision and they ended up not merging, and they averted a very serious disaster for themselves.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, we mentioned Jack Welch earlier, and I have actually a lot of respect for many of the things that he did in terms of delayering management and breaking down the walls between organizations and whatnot. But what you were just saying describes almost perfectly their entry into the investment banking industry and when they bought Kidder Peabody. And he admits it himself in his books. He says, “Hey, when they came to me and said, ‘Well yeah, we had a terrible year, but we’ve got to give this guy a $12 million bonus’,” he said, “No, no. At GE when you have a terrible year, you don’t get a big bonus.” He said, “Well yeah, but he’ll go someplace else.” And at that point, he realized that the culture was simply not compatible, that there were no changes that they could make that would have the sort of performance-oriented culture that he had instilled at GE work in that particular industry with the people that were apparently needed for success in that industry.

Gleb Tsipursky: Yep. I think that’s a perfect example where business leaders, again, they come from their own culture. They don’t understand that. They don’t notice how important the internal culture, internal systems and processes are when they try to do mergers and acquisitions. And it’s the same thing where you give the example when somebody is going from six car dealerships where the culture is relatively similar in many car dealerships, when they’re going to a different industry and they’re assuming, they’re making the same assumptions in their decisions as though they’re in the car automotive dealerships, whereas they’re really not. And they have different cultures, different assumptions, and that’s a big, big problem. This assumption problem, there’s one of the cognitive biases that people deal with, but we all deal with it and we all suffer from it and we all need to change is called the false consensus effect.

The false consensus effect has to do with that we assume other people are much more like us than they actually are. Again, we assume that other people are much more like us, that they think like us, they feel like us, they have the same patterns, norms and ethics than we do, but it’s actually not true. There’s much more difference between people, between the values, between assumptions of various business leaders, various industries, various people in different positions, even personalities than we tend to assume. This is something we really need to be very careful about, avoiding these dangerous assumptions, which we tend to run with.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think a one example of that that our listeners might be familiar with is JCPenney who a few years ago, brought in a senior Apple executive as CEO to revamp their stores, because Apple was considered to be one of the best retailers on the planet with their amazing stores and so on. And it turned out that his gut feel for what customers really wanted was totally wrong. He did away with sales. He made the stores a lot more open-feeling with less inventory, and customers basically stopped coming. He nearly bankrupt the company in the space of a year. But it wasn’t that these things were necessarily bad, but they might’ve worked had, say, Microsoft hired him to do their stores, but were not necessarily good for primarily a sort of a middle-class to budget apparel retailer.

Gleb Tsipursky: That’s a great example. And of course just as problematic, think about Sears. Sears and Kmart, where they joined forces, and where that was a really bad idea. That new leadership there just didn’t invest into the stores. They thought that having the footprint of the stores was sufficient, and they joined two brands that were weak in their own right, and it was less than the sum of their parts. That’s another bad example of where Sears and Kmart together end up being bankrupt.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yep. Talk about hiring a little bit. It seems like that’s an area where we do tend to, all of us tend to trust our gut. And the research, I know that you mentioned the book, and I’ve seen that for years. That basically says that interviews are one of the worst ways to evaluate candidates. Talk a little bit about that.

Gleb Tsipursky: Sure. It’s very typical for, especially medium, small-size businesses to just trust their guts when they do interviews. Leaders would interview someone and say, “Hey, I like this person or I don’t like this person. Hire them.” I was working with a startup that was bringing on… It was a technology startup, and the technology leader, the CEO, brought in his friend from the corporate world into the startup. He had an interview, thought the friend would do great and brought this friend in. And it turned out that the friend thought that he wanted to work in a startup environment, but he was not prepared to deal with the chaos. I mean, he wanted the money, he wanted the glory, but he wasn’t prepared to deal with the chaos of the startup environment, and the chaos of a startup environment was just not a good fit for him.

And this friend felt that the CEO would never fire him because he was a friend, so that caused a lot of tensions and conflicts. The CEO had trouble having difficult conversations with the friend. Eventually, after we talked, after I and the CEO talked for a while, the CEO put the friend on probation and the friend and the friend ended up leaving for corporate America before he could get fired. And that was one example of many examples where we can’t trust our guts on interviews. Why is that? Because there are some people who are great at interviewing, but they’re really bad at job performance. The research says, and it’s hard to believe because we trust our guts. It’s hard to believe, but that’s what the research says, that interviews, unstructured interviews don’t indicate anything about future performance.

They don’t indicate anything about the ability of the candidate to perform in the future. They just indicate things about the candidate being good conversationalist and being able to click. And this feeling of clicking is one of the most dangerous things that you can have in business, because that gut comfort, our connection to someone is false. Very often it’s false. The gut feeling of connection just means that you feel that this person is part of your tribe. And one of the worst things you can do in a business is hire people who are just like you, who are part of your tribe, because then you don’t get any diversity in the business. You don’t get diversity of thought. I’m not talking simply about issues of sex or gender, color of skin, politics, whatever. I’m talking about diversity of thought, having people who think differently from you. And if you don’t have diversity of thought, you’ll be making terrible decisions, because you will not be able to compliment each other’s weaknesses and strengthen each other’s strengths.

That’s very dangerous for businesses. It’s one of the biggest dangers for businesses that are going from small to medium out there. And of course it’s a huge problem for marketers who hire other people who are like them and market to people who are like them, and then they miss out whole market segments and they make mistakes about who their target audiences are. It’s very bad to do unstructured interviews. We now have extensive research on this, and this is one of the biggest issues that you want to think about more broadly. Not trusting your gut, not thinking that just because you feel something is true that it is actually true. Not thinking that just because you feel something’s right, it is actually right.

I mean, people who are depressed think that the world is bad just because they feel depressed. People who are anxious think that the world is a threat, is threatening just because they’re anxious, and this is a broader tendency. Depression, anxiety are just two recognized mental health conditions. People who are optimistic think the world is good just because they’re optimistic. These are very dangerous things, and these are very dangerous cognitive biases to fall into.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I’ve always said that interviews are probably good for hiring in-person salespeople because it’s almost like a work sample. You’re actually evaluating how they’re performing in a one-on-one office setting, but for just about everything else. And of course, the farther you get from that, say you’re trying to hire developers or something, then it’s probably the worst possible tool you could use.

Gleb Tsipursky: Yes. And also for salespeople, if you want to hire salespeople who are going to be selling to different people than your current sales team, you don’t want to have the in-person interview be a determinant of their success.

Roger Dooley: Right. That’s a good point, and I think you can flip that discussion around too, because there are two sides to each interview and you’ve also got the job seeker. And your little story reminded me of one from my personal background where a lady that I worked with decided to open a restaurant, and her mother-in-law came in as partner and operator with her, and they vowed to run this business. And about a month in, it became really clear that the mother-in-law did not realize that running this particular kind of restaurant, which involved starting cooking at like 2:00 in the morning to get ready for the morning rush was a key part of it. And it was like that was incompatible with the way she wanted to live her life.

As a result, ended up being a difficult situation that they ended up working out, but this great business plan went awry, I think because in that case, the mother-in-law made a sort of a gut decision saying, “Oh wow, really, this would be fun being in a restaurant business.” I think she visualized sort of the welcoming guests into the restaurant, and people recognizing her as a proprietor, and all the good stuff that goes with being in a restaurant, but without necessarily looking at the other aspects. If you’re looking at, in that case, it was sort of a business partnership, but the same thing applies for jobs. The person who went into that startup, I mean, that was partly their failure of analysis too, where they didn’t look at it sufficiently logical, rational, and analytical approach. They said, “Oh wow, I really want to be part of a startup.”

Gleb Tsipursky: Yes, and a lot of people, this is the problem with a lot of business leaders. They tend to be very optimistic. Now, optimism is something that is just a part of me. I’m a business leader. I run my own training, consulting, and coaching company, Disaster Avoidance Experts, disasterevoidanceexperts.com, and this is definitely something I feel myself. The large majority of people who start up businesses are optimists. They think the grass is green on the other side. They think the glass is half full. And this is something good in there that motivates them, so it’s good to use the optimism for motivation. It’s not good to use optimism for the decision-making process. You want to look at all the threats. You want to look at all the problems. I’ve learned that I tend to underestimate risks, so I tend to inflate the risks based on my tendency to underestimate them.

And so I’ve learned a variety of techniques that based on the research of how do you address optimism bias in myself. It’s something that you really need to learn, and you need to learn what are your own cognitive biases. My book has an assessment at the very end in Chapter 7, Dangerous Judgment Errors in the Workplace. That goes for all the 30 most dangerous judgment errors in professional settings, and helps you assess to which ones you and your team are most vulnerable to. This is something that you really need to be aware of and be able to address in yourself.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and that too works both ways, because I know people who are so pessimistic that they won’t travel to Paris because two years ago there was a terrorist incident in which three people were killed. It’s like, okay, this is a city of millions of people and that was years ago. This has absolutely nothing to do with the probability that anything’s going to happen to you, but just sort of the way they make decisions. Let me ask you one last question, Gleb. In recent years, neuroscientists have found that our guts actually have much larger concentrations of neurons than was previously thought. And people have said sort of informally that, “Well, this gives sort of a new meaning to gut decision,” and they suggest that this is actually part of our decision-making system. I’m just curious whether, since you’re focused on gut reactions, whether you have looked at that field at all and what your take is on all that.

Gleb Tsipursky: Sure. This is all part of changing our mental habits, and it’s not a bad thing to use your emotions. You want to be very much in touch with your emotions. The research says that about 80 to 90 percent of our decision-making is driven by our emotions, so we can’t get away from it. We’re motivated by our emotions. The crucial thing is to be able to shift your emotions to change how you feel, to have more healthy mental habits just as you have healthy physical habits. Let’s say about diet, you might want to eat that third chocolate chip cookie, right? But you’ve probably learned over time-

Roger Dooley: Yeah, you’ve seen me eat chocolate chip cookies. I can tell, Gleb.

Gleb Tsipursky: Yeah, there you go, Roger. And it’s something that you’ve probably learned over time is not the best idea, so you’ve changed your diet to be more healthy, and now you eat somewhat different things. And as you change your diet to be more healthy, many people, very many people find that they actually have a less of a desire for chocolate chip cookies and they have more of a desire for healthy things, tofu and whatnot, lean meats.

And that is the part of the same thing that changes. You have healthy physical habits around your diet. You do more exercise. And you also need to have healthy mental habits. Changing your mental habits to address each of the cognitive biases that cause you problems and in order to succeed. So it’s not about not using your emotions, it’s about changing your emotions to make sure that they align you with your actual goals, with your long-term future as opposed to just doing the primitive savage thing. It’s just like the difference between eating with your hands and eating with a fork and knife. Very unnatural to eat with a fork and knife, you know? But right now, you’d feel very wrong and bad not eating, in most cases, eating things with your hands that should be eaten with a fork and knife. And so that’s the same sort of thing.

You change your mental habits, you change your feelings to go from the natural state to the civilized state, to go from the savage state to the modern contemporary state. And that’s what my book is about. That’s what my work is about. Helping people avoid disasters, seize opportunities for making the best decisions.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, today we are speaking with Gleb Tsipursky, author of the new book, Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. Gleb, how can people find you?

Gleb Tsipursky: They can check out my book on bookstores anywhere and everywhere. Again, it’s Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. They can go on my website to check out the company, blogs, videos, podcasts. disasteravoidanceexperts.com. Again, that’s disasteravoidanceexperts.com. They can connect with me on LinkedIn. That’s Dr. Gleb Tsipursky. Again, Dr. G-L-E-B T-S-I-P-U-R-S-K-Y on LinkedIn. And finally, if you have any questions about anything I’ve said on this show, happy to answer. Email me at gleb, G-L-E-B @disasteravoidanceexperts.com. That’s again, [email protected].

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to all of those places and to any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have a transcript of our conversation there too. Gleb, thanks for being on the show. I hope we prevented at least one or two disasters for our listeners.

Gleb Tsipursky: I hope very much that’s the case as well. And thanks again Roger, and congrats again on your book. That’s a great accomplishment.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.