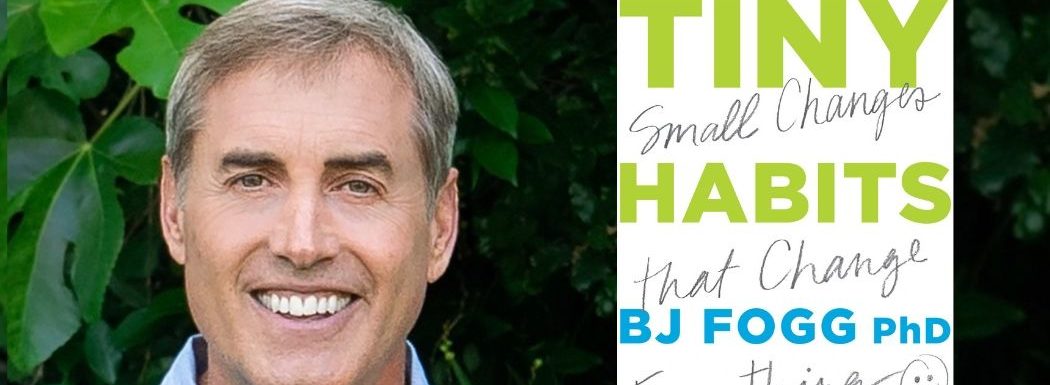

BJ Fogg is the founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University and one of the best known behavioral scientists out there. He teaches industry innovators how human behavior really works, and he created the Tiny Habits Academy to help people around the world improve their lives and the lives of their clients.

In this episode, BJ shares insights from his book, Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything, and explains how to quickly and easily improve your habits. Listen in to learn what it takes to increase your motivation, how to break bad habits, and what we can all do to design for positive change.

Learn how to use small changes to create positive habits quickly and easily with @bjfogg, author of TINY HABITS. #habits #behaviordesign Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to make small changes to improve your life.

- What it takes to design for positive change.

- The problems Tiny Habits is solving right now.

- BJ’s behavior model and what it entails.

- How to increase your motivation.

Key Resources for BJ Fogg:

- Connect with BJ Fogg: Website | Twitter | Instagram

- Amazon: Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything

- Kindle: Tiny Habits

- BJ Fogg – Behavior Design

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

- Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.” To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence, I’m Roger Dooley. Today’s guest doesn’t need much introduction, and not only because he’s been on the show before. B.J. Fogg is one of the best known behavioral scientists, and founded the behavior design lab at Stanford University. He’s the originator of the Fogg behavior model, a concept that underlies my persuasion slide framework and a lot of what’s in my book, Friction. He’s also the founder of the Tiny Habits Academy and the author of the new book, Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything. Welcome back BJ.B.J. Fogg: Roger, it’s great to talk to you again.Roger Dooley: Great. You know, BJ, the idea of applying behavioral science to real world problems has gotten a lot of traction in the last decade or so. Can you start by explaining the origins of the behavior design lab at Stanford and telling us the sort of problems that you’re working on now?B.J. Fogg: Yeah, so I actually started a lab in the 1990s and at the time I was studying what I called persuasive technology, which is how computers can influence people’s attitudes and behaviors. And so, that was the lab and our work until about 2009. And at that point, our research interests changed, and we were just more interested in health habits and human behavior more generally. It had nothing to do with technology.

So it was 2011 we changed the name of the lab to the Behavior Design Lab, and we really don’t look at technology per se. It’s more just about how human behavior works, and how you can design for positive changes. And that’s what the lab is now at Stanford.

Current projects include … we have a project about screen time and we’ve developed something we call it screen-time genie, where people can use this little online wizard, answer some questions, and then it goes into our database of like 150 solutions. There’s an algorithm and then it matches you with the best way to reduce screen time. We’re doing a project about teaching behavior design, how human behavior works to professionals and climate action, and we’re also doing a project that’s developing a way to teach students how to be more financially secure, develop good financial habits. So, those are the current projects in the Behavior Design Lab.

Roger Dooley: I’m curious, are you seeing some progress in the whole screen time thing? It seems like today, about every second book is some kind of a digital detox book, or something telling people how to get off their screens. But I guess the fact that there are so many books about it indicates that it’s a challenging problem.

B.J. Fogg: It is a funny problem. There’s a lot of media out there about it, a lot of hand wringing. But what we found, Roger, early on when we’re like, “Hey, do you want to reduce screen time?” A lot of people, and I don’t have the numbers here in front of me, we quantified it. But a lot of people say, “Yeah, it’s a problem, but it’s not a problem for me. It’s a problem for my spouse. It’s a problem for my kids.”

So there does seem to be this sense of people do agree that we’re on devices too much, but often the fingers are pointed the other direction of who really needs to change. Even so, one big takeaway in behavior design generally is, you help people do what they want to do. if somebody doesn’t really want to reduce their screen time, then they’re not the customer for our screen-time genie. Just like if somebody doesn’t want to share photos, then Instagram shouldn’t try to get them to be customers.

Roger Dooley: Right. What you’re saying there sounds a little bit like the admission that other people are probably biased. In fact, I know other people are biased, but I’m not biased. Of course, behavioral science would tell us a different story, but people always see these flaws in others.

B.J. Fogg: And I don’t want to make too big a point of that, but that was something that we found. The project has been groundbreaking, in that we’ve gathered over 150 different solutions. It’s a huge library of solutions from all over the world. They’d never been put together before. So we did that, we compiled them and we’ll continue to do so. And then there’s a way to match people with the best solutions for them, and that’s really the innovation there. And that’s the platform for research there.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, early in the book, B.J., you say that information alone doesn’t change behavior. And I guess that probably sounds pretty obvious to our listeners, but people are always surprised when information does change behavior. Your doctor tells you to lose 20 pounds to reduce your risk of a heart attack. And of course heart attacks are pretty serious consequence. But a year later, you come back in and nothing much has changed. Do you think that professionals like doctors, and folks in all kinds of other industries and professions are coming around on this topic yet?

B.J. Fogg: Yes, for sure. I mean, what I find, I teach people from so many industries about behavior design, know how human behavior really works and how to design for successful outcomes and they come from all sorts of places, including the medical field. The more experienced somebody is in trying to help change their behavior, they’re in the trenches every day working with patients or with clients or whatever. Once they see the behavior model, they’re like, “Oh my gosh, there it is.” And once they understand tiny habits, they’re like, “Yep, that’s exactly what I’ve found over 10 or 20 years of work, they just didn’t have a framework for it.” So, the practitioners, the people in the ivory tower, the graduate students who’ve never really done any real behavior change, the engineers coding the apps, I’m generalizing here, but just forgive me for a moment, those people tend to be very rational and think, “Oh, if we just give people data, if we just give them the facts, they will change.”

And as you suggested, Roger, that doesn’t work very well. And the more experienced somebody is, the more they understand that doesn’t work and they’re really eager to find what does work. Now, like I said, if somebody has been in the trenches, five or 10 or 15 years, Dave stumbled around and he’s figured some things out. They figured some things out on their own and they’ve figured out what works. It doesn’t necessarily match their academic training because there’s so much they get taught in those circles that does not work.

So it’s really fun for me to share behavior design and the methods there and there’s this resonance like, “Yeah, there it is. You’ve structured it, you’ve given things names. That’s what’s been working for me. Thank you very much for putting it together.”

Roger Dooley: I understand what you mean, B.J., About the intuitive appeal of the behavior model. I first sought, we were both speaking at a conference and that was the first time I had run across when I saw your presentation and it immediately sort of clicked and I said, “Oh yeah”, and I’m sure many other people have had that same sort of a-ha moment since that’s what underlies the tiny habits concept, I know we can’t work visually here, this is an audio recording, but can you sort of give a brief explanation of the behavior model?

B.J. Fogg: Yeah, so the behavior model, it goes like this.

Roger Dooley: And I’m sorry you don’t have a whiteboard to work with it. That would make a lot easier.

B.J. Fogg: You know how much I like working on my boards. The behavior model goes like this behavior happens when three things come together at the same moment. Motivation to do that behavior, ability to do the behavior and a prompt and the prompt is a thing that says do this now.

And if any one of those three things is missing, the behavior won’t happen. And that’s fundamentally the model. There’s a graphical version of it with a curved line and that shows that motivation and ability, you can trade one off for the other. So if a behavior is very hard to do then motivation has to be high. If the behavior is really easy to do, the motivation would be higher low. It shows even though that graph and people can go to behaviormodel.org and see the graphical version, that line as simple as it looks, it really shows an important relationship between ability, essentially, simplicity and motivation.

And as you know from my work, I’m a huge, huge, huge fan of simplicity because if something’s really easy to do, if you have high ability to do something then you don’t need much motivation to do it. And that insight basically opened the door to the tiny habits method where you just pick a really, really, really simple habit and then when your motivation shifts around you can still do the habits because they’re so easy.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and you’re certainly not the only fan of that. Richard Taylor has said, “If you want to get people to do something, make it easy.” And you know, it seems like a rather simple concept, but when people have asked him to help governments and corporations have asked him to help solve these difficult problems, it seems like making things easy is more difficult than you know, sprinkling some magic motivation dust down under or something.

But anyway, that is such an important message of throughout whether it’s certainly for habit formation, for any kind of creating behavior, changing behaviors. There are a lot of people who would agree with you, but getting people to actually practice that sometimes a little bit harder.

B.J. Fogg: And it’s kind of built into industries. I mean the more expert you are at something, usually the less good you are at figuring out how hard that’s going to be for somebody. Let’s say you’re an expert in financial planning and budgeting. Somebody comes in to talk to you and you’re like, “Oh, set up a budget.”

And in your mind as an expert, that’s easy. And that person’s mind sitting there looking at you, they’re like, “You might as well just ask me to build a spaceship. I don’t know how to do that.” So, when experts, and this is a systematic problem, when experts design the behavior change program, they forgot what it’s like not to know and so they’re often asking people to do things that are way too hard.

There’s a big difference between having expertise in a domain like financial planning or nutrition and the expertise it takes to design a program that changes behavior. And that’s one of the things I like to call out in the medical profession and elsewhere is don’t have the medical scientist design the behavior change part of the intervention because that’s not their expertise. Their expertise is figuring out the science of how we should be moving and eating and so on, and they’re out of their depth if you ask them to design the change program.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. BJ, in our last conversation we talked a little bit about your tiny habits method and this was before the book came out. Probably the very first people to teach habit formation whenever, I don’t know when that happened, it was probably quite a while ago.

They would typically suggest starting small. If you want to become a runner, you don’t start by running a marathon. You walk a half a mile and maybe eventually work up to jogging a mile or something and keep progressing. But the counterintuitive part, at least for me of your method, is that the initial startup stage really is not particularly effective at accomplishing the goal.

Like at least if you walk a half a mile, you can say, well, you’ve done something to improve your cardiovascular fitness, but flossing one tooth, which I think was an example we talked about last time, really is not going to get you much acclaim from your dentist. How did you come up with a tiny habits concept?

B.J. Fogg: But it does, Roger. It does. So your dentist and your dental hygienists will love you because it does cascade to the bigger habit of flossing on your teeth.

Roger Dooley: Oh, it was certainly the habit itself would be, but if you showed up after merely flossing one tooth saying, wow, you’ve done a nice job on the number 23 there.

B.J. Fogg: It was exactly that example. It was exactly that that helped me start exploring this thing that became tiny habits. Going to the dentist feeling bad that my gums are bleeding and they said, “Oh, did you floss?” And it’s like, “Well I did this morning and I will today”, and you know the typical scenario and when I thought about it, I thought, you know what? I know how to floss all my teeth. I know how to do that. What I don’t know how to do is floss automatically. Like just boom without thinking. I don’t have philosophy to habit. And so what I realized is it doesn’t matter that I floss all my teeth. What I need to do is focus on making flossing a habit and I can do that more readily if I scale it way back, and I just lost one tooth, and once that’s wired in, it’s a habit, then I can do all my teeth.

And that’s exactly what most people do with tiny habits. You start really tiny, you find where it fits in your life naturally. You get it wired in through emotion, through a technique we call celebration. And then once you have the habit, you can do more. You can floss all your teeth, you can run further, you can do more pushups and so on. The tiny habits method some ways initiated with the insight that the challenge isn’t the whole behavior. The challenge is just doing any part of that behavior as a habit. And that’s what I focused in on.

Roger Dooley: Right. And looking at the balance between motivation and ability or ease of doing it, the day before you’re going to the dentist you think, “Oh crap”, you’re really motivated to floss because you know you wouldn’t want them to think you didn’t floss. Of course they can tell because-

B.J. Fogg: They know, they know.

Roger Dooley: But you’re in probably the day when you get back to your motivation is pretty high because they’ve sort of read you the right act about why it’s important, but eventually your motivation declines. And the certainly hasn’t gotten any easier to do. So, that’s the key thing about flossing one tooth is that you are making it super, super easy. You don’t need a lot of motivation.

B.J. Fogg: Yeah. And you’ve opened the door for me to talk about how human motivation, we are really bad at acknowledging the fact that our motivation goes up and down over time. In that moment when you’re the dentist chair and the hygienist is telling you how important it is to floss, to keep your teeth, you’re super motivated and you can’t anticipate that three or four days from now your motivation will drop. In that moment you probably believe, yeah, I’m going to do it. This time I will. I really will. And then three to four days later that motivation sags. You’re motivated to do something else and so on. We seem to be as human beings very bad at understanding that even though I’m feeling super motivated in this moment, like January 1st, or sit in the dentist chair, that your motivation will vary over time.

And what that means is when you’re in the dentist chair on January 1st or just go, “Man, I’m going to run for an hour a day” or “I’m going to do all my teeth” you’re setting yourself up to fail later because it’s very hard to control the swings in motivation and that’s what tiny habits accounts for. Is like guess what you can’t always rely on your motivation being high. So let’s short circuit or circumvent that problem and make the habit really small. Now, you can do more anytime you want. You can run that for an hour, you floss all your teeth, you can do the big habit anytime you want. The mindset shift with tiny habits is the tiniest version is always okay and that’s always a success and you do more if you want to and you can.

Roger Dooley: Right. The context thing is interesting in I believe, I think it’s next week I’ve got a conversation coming up with Will Leach who also engages in behavior design and one of his insights is his book is Marketing to Mindstates and unlike many marketers who assume that once you’ve identified your customer’s persona or perhaps three types of customer personas that that’s fixed.

And just as we were talking about with your motivation to floss your teeth when you’re sitting in the dentist chair versus the day you get home versus three weeks from then your mind state has changed and your behavior will change. And so I think the lesson there for marketers too.

B.J. Fogg: Right on. Yeah. And then there’s a connection here that everyone understands is that there’s a season or a time to prompt people to buy something or do things. Our motivation can surge. Like if there’s something on the news about an earthquake or a fire or something like that, then the motivation goes up to buying insurance or get prepared. There’s something in the news about, let’s say prostate cancer. A bunch of men are going to go get tested for that, but that they call it a news cycle, I think. That fades just like our motivation to do the behavior fades. And so from a sales perspective anyway, and you need to strike … what’s that saying? Strike while the iron is hot.

Roger Dooley: Yes.

B.J. Fogg: Yeah. Timing matters and that is exactly because our motivation fluctuates over time.

Roger Dooley: Right. Gyms sign up a million new members on the 1st of January and fortunately for the gym regulars, most of those folks have dropped out by the beginning of February or so. When we last spoke, I was in my own little tiny habit experiment and I can tell our listeners that it was indeed working.

I was starting with one pushup after every bathroom visit at home, not at the office or in a restaurant just at home. And I had worked up, I think when you’re talking about eight or so, got up to about a dozen. Unfortunately I had a shoulder aggravation flare ups and I had to quit. But I did find it to be a very effective way to build a habit that was actually pretty challenging for me.

I mean when I started others I would not have been capable of doing that many pushups. But this very small sort of little intervention really changed my ability in that area. It does work. So I’ll give you that. I’m trying to figure out what to substitute for that to try and-

B.J. Fogg: Squats.

Roger Dooley: The only thing is I can do quite a few of those. I mean it’s not a tiny habit. I’m experimenting with adding some weight to that to just make it a little bit more challenging and make it a tinier habit.

B.J. Fogg: Well, what I’m doing right now in my own life, Roger, so I’ll share this and the listeners may not care, but as you know, I’ve done pushups after I peed for years and built up to lots of pushups and then I became interested in being able to squat, not just strengthen my legs but squat all the way down.

Roger Dooley: A range of motion?

B.J. Fogg: Well all the way down. So I could just sit there like you see people in Asia do and an American from California, like I can’t. So I’ve been working on that and I’m getting there. That’s what I do is I just, yeah. And I do it slow and I don’t want to damage my knees. But you can take that, what should I say, location for a habit and if the pushups don’t delight you or you have some reason you can’t do it, like the shoulder injury, you can transplant in a different habit because you know it’s a great place to do a short little behavior. And so right now I am doing these, I don’t know what to call it. It’s kind of embarrassing.

Like you just squat all the way down to the ground. Only your feet are touching and at first you fall over. At least I did. And now I can actually sort of do it, but I’m still working on it. So that’s what I’m doing now with that.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well yeah, I may have to give that a try. You know we have something else in common, B.J., and that is shower maintenance. Both have partners who have a thing about that in our shower. We’ve got a couple of glass walls and if you don’t squeegee them or wipe them down, you will get water spots. Now my own preferred approach to that would be to forgo daily squeegeeing instead of just cleaning the glass every week or two, preferably someone else performing the glass cleaning step. But my wife was not quite as enthused by that approach and she simply raised my motivation enough so that now she’s trained me to squeegee after every shower. And so I’m, can you explain your-

B.J. Fogg: Yeah, well, in my case, my partner is a clean freak and in my case it wasn’t so much motivation and this translates directly across the business issues and other things in our life cause I didn’t know exactly what to do. The behavior wasn’t clear to me. And again, I’ll go back to this, the problem with the experts or even managers, it’s like, “Oh you need to file your expense report or you need to follow up with your clients or you need to stay in constant contact”. Now in your mind as the expert, that behavior might be really clear. But the person hearing like, “Oh, stay in constant contact with your clients”, they don’t know what that behavior actually is.

And so a big part of helping people create these habits, whether it’s a onetime behavior or habits like squeegeeing the showers and staying in constant contact, is to be really clear what is the behavior, what is the exact behavior, number one. And then number two. If you think of my behavior model, that’s the B in behavior model. Define what that B is, don’t have it be something abstract.

After that make it really easy to do. And then after that, make sure there’s a prompt. And that’s essentially behavior design, at least from a design perspective in a nutshell, what’s the behavior? How do you make it really simple? And then what’s going to prompt or remind this behavior. Thousands of steps. And essentially tiny habits is that, but applied to habits with an additional step of where you can rewire your brain. So it becomes a habit.

Roger Dooley: Well, you know with showers there’s a pretty clear prompt, I guess you finish the shower and you see the water on the glass or standing on the floor or whatever. And so you realize it’s time to start the behavior, but other things, not so obvious. Explain how anchors work.

B.J. Fogg: Yeah. So in tiny habits, I picked the word anchor. Let me back up a little bit. Just about 30 seconds ago, I said you need to design a prompt. What’s going to remind you to do this new habit, whether it’s eating some cauliflower or getting out your vitamins or doing pushups. In the tiny habits method the hack there, you don’t set alarms, you don’t put up post it notes. Instead you find a routine you already do that then can serve as your reminder for the new habit. And so let’s say turning off the shower becomes a reminder to pick up the squeegee. You already turn off the shower, oops, you didn’t have the habit of picking up the squeegee. Then, that’s the new habit you’re working on. And to find where it fits naturally. Now the routine you already have, like turning off the shower, in tiny habits, I call that an anchor.

It’s something firm in your life that already exists that you can attach the new habit to. So boom, we all turn off the shower. That’s a solid routine. That’s an anchor. What new habit do you want to attach to that? And there’s a lot of things you could do. You could pick up the squeegee and start squeegeeing. You could do squats, you could do pushups, you could have a slight meditation, you could put moisturizer on your face. For any given routine you already have that you do reliably, you can use that as an anchor to attach a new habit to.

And in fact, that’s one of the ways to create new habits is you don’t start with the actual habit. You start with these anchors, these routines you have and you go, man, what could fit easily and naturally, right after I turn off the shower and you come up with something and you try it and if it works, you keep going. And if it doesn’t, you come up with something different. Like, okay, the pushups didn’t work after I turn off the shower. So maybe this is a good moment to have three bet breaths of gratitude. And you find that for you that works. And boom, you’ve just worked on a little gratitude moment into your daily routine.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. How do you stop a bad habit? It seems like a different kind of problem, but can you address it in some of the same way?

B.J. Fogg: Yes, it is. Well, everything, all behaviors, good habits, bad habits, one time behaviors always come back to motivation, ability and prompt. The behavior model applies to all types. And when it comes to what we call bad habits, that can be a thornier issue. There are certainly some habits. And then in the book, Tiny Habits, I call them free fall habits.

Where guess what? You are in free fall, you’re not going to be able to stop this yourself and you need professional help. And even reading my book is not sufficient. Go get professional help. And so let’s not talk about those kinds of habits because there are experts in the world and there are some really serious addictions and life-threatening problems where people need help. But for things like snacking too much or social media or drinking too much soda or things like that, certainly those are not great habits and rather than thinking about breaking them, I’m putting out there a different way of thinking about it and I talk about untangling bad habits, so break is the wrong verb. Break implies that if I just put a lot of energy in this moment, then my snacking, all my bad snacking habits will go away.

If I just do it in one moment, I break it and it doesn’t work like that. It’s more of an untangling then you probably have five or eight or 12 different times during the day you snack and each one of those is like a tangle in a big knot. And in Tiny Habits I walk people through step by step the process of how to figure out what those little snarls are in the knot and then how to untangle them systematically and pretty easily. And the headline here, I guess in some ways to finish my answer, there’s a whole chapter on it, but to finish my answer is once you understand what all those tangles are in your snacking habit, your smoking habit or your social media habit, then you focus on the easiest one to stop, not the hardest one, the easiest one, and it’s always going to come down to can I remove the prompt, can I make it harder to do or can I remove the motivation?

If you can do any of those three, you’re on your way and if that doesn’t work, then there’s other things you can do that I explain in Tiny Habits. But I think the surprise for people it’s twofold. One, it’s not break bad habits, it’s untangle. And then two, you start with the easiest angle, get that done and go to the next one. And you build momentum and skills and confidence that you can do the rest. And that’s how it works. Just like untangling, say Christmas lights that are all tangled up. Well you don’t start with the hardest tangle and you start with the easiest thing and then pretty soon it’s done.

Roger Dooley: So, if you find that you’re snacking, if you go into the kitchen for a fresh cup of coffee, for example, perhaps you could put the coffee machine in your office or someplace not adjacent to the food so you wouldn’t have that linkage between the two and at least you could still walk into the kitchen or walk over wherever the food is. But you would be much less likely to do that.

B.J. Fogg: Well, here’s what happens. You’re exactly right. But let’s say somebody is working on the snacking … well, in Tiny Habits I tell the true story of Juni who when she came and worked with me for professional reason, she learned behavior design as a professional and the first thing she did to introduce herself to everybody in the group was, hi, I’m Juni and I’m addicted to sugar. And I was like, wow, this is not a self-help event. Thank you for sharing that Juni. Well, what she learned about behavior design helped her go home and tackle the sugar habit. And where she started is where I advocate, where people start for the really hardest habits to stop. You start with creating new good habits. You set aside the sugar problem for now and instead you focus on creating these new positive habits for a few reasons.

One is you develop more skills and confidence. You can change by doing all these, using the tiny habits method to develop a new habit of flossing or taking your vitamins or texting your mom or wiping the kitchen counter. And then the thing that it does, it’s even more transformative is it changes how you think about yourself. Your identity shifts and you start thinking, I’m the kind of person who can change. Wow. I’m wiping the kitchen counter and I’m putting my shoes away all the time. Wow, I can change. And then that helps you then turn to the bigger problem. In this case, Juni’s sugar addiction. And then she was able to untangle that and she was so delighted when emailed me a few months later and said, “B.J., I am sugar free, I’m sugar free.” And that was a huge thing for her, but it was a process and it wasn’t magic. It was a process applying behavior design and she got there.

Roger Dooley: I think there’s definitely a tendency for folks to get caught up in this sort of negative self talk, I can’t quit sugar because I have no willpower. And what you’re saying is, first of all, you shouldn’t be depending on willpower to quit, but by adopting these other behaviors, you’re also putting the lie to that statement that you can’t change your behavior. So that makes a huge amount of sense. Yeah. Anything else our listeners should know about tiny habits or habit formation in general, B.J.? I mean, other than the other many, many pages in the book. The Tiny Habits it’s is not a tiny book, by the way. I thought there might be one of these little slender under sized volumes.

B.J. Fogg: I was so tempted to do that and think how much easier would have been to write. But what I’m delighted about, and I will answer your question Roger, but I’ll answer in the context of yeah, it’s a 300 page book, but I will answer what they should know. This was just a great opportunity, this book to go into behavior design, so it’s not just tiny habits, it’s the broader work of behavior design that I’ve developed over 20 years and show people, here’s how human behavior works. There’s a system to it. There’s a system of how to think about it, how to design for it. One of the techniques is tiny habits and to get that stuff out there, which I got out for the first time ever in this format … okay, so you probably know and looking at my work a few years ago, it’s like B.J., How do I learn more about this or this or this and this? And it’s like, that’s all Roger, there’s no great place to learn all of this. Well now there is in Tiny Habits, so that’s why it’s a 300 page books.

However, there’s pictures, there’s graphics, there’s lots of true stories like Juni’s story and so on. What people should know is this. It is easier to create habits than you think if you do it the right way. And the fact that it’s easy I think means you shouldn’t delay you shouldn’t have to wait for new years to do it. You could start creating your habits anytime and the two overriding principles that are in the book and in my work, I called them maxims. Number one, help yourself do what you already want to do. As you’re looking at change in your life and creating habits, focus on habits that you want, not things that feel like should. So help yourself do what you already want to do.

Now in the business arena where I’ve taught this a lot for people creating products and services that maxim is help people do what they already want to do. As you’re creating a product or service, you’ve got to help people do what they already want to do. Back to the Instagram thing, if people don’t want to share photos and they’re not your customers. You’re helping people do what they already want to do. Second maxim applied to one’s own life. And that’s what Tiny Habits it’s about. It’s behavior design for everyday people. Second maxim is help yourself feel successful because it’s the feeling of success as you do a new habit that rewires your brain and makes it automatic, it’s not repetition that creates the habit. So, that meme and that thing is actually not accurate. Repetition correlates with habit formation, but it doesn’t cause the habit to form.

Look carefully at the studies that people signed and you’ll see these are correlations, this is not causal. What’s causal is the emotion that you feel and that’s what rewires the brain. So in Tiny Habits, you hack that with a method that I described in the book called celebration. And there’s a way that you can create an emotion that wires the habit and quickly. Now, because I think most people listening to this are business folks, you can take that maxim of help yourself feel successful. And for customers or for products is help people feel successful. That’s what keeps them using your product or service. That’s what makes them engage. That’s what makes them dance. And if you look at any product or service that you love and use all the time, it’s doing both those things. It’s helping you do what you already want to do and you feel successful using it.

And I can find no exception to that. Everything that’s gone big or everything that people really, really love, from sunscreen to an app, to a car or running shoes to cable TV of whatever flavor. If you love it and use it all the time, it’s doing those two things and in Tiny Habits I then take those two business maxims that I’ve been teaching for years and I help people see how it applies to them. And so those are the two, I guess the two things from the book, it’s that help yourself do what you already want to do. That means don’t beat yourself up, don’t force yourself to do stuff you don’t want to and then help yourself feel successful.

And part of that is lowering the bar. Like we talked about Roger, like you’ll be more successful if you reduce, I mean oddly enough, lower your expectations. Set the bar low, succeed on that. If you want to do more like floss all your teeth, awesome. That’s extra credit, but that’s a way to help yourself feel successful as you’re creating that habit.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, I think that’s a great place to wrap up here, great takeaways, but I certainly encourage our listeners to get the entire book because there’s a lot more than that in there and I will remind everybody that today we are speaking with B.J. Fogg, founder of Stanford’s Behavior Design Lab and the Tiny Habits Academy and also the author of the new book, Tiny Habits, The Small Changes That Change Everything. B.J., how can people find you and your ideas?

B.J. Fogg: Pretty easy. Tiny Habits, go to tinyhabits.com. For myself, my broader work, bjfogg.com and it sounds like they’re probably the good starting points right there.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link to those places and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. BJ, thanks so much for being on the show. It’s always a pleasure.

B.J. Fogg: Oh, thank you, Roger.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.