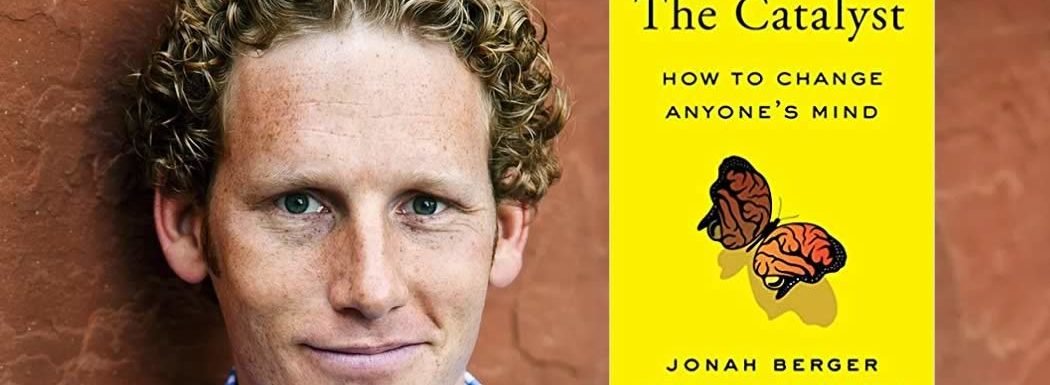

Jonah Berger is a marketing professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, an internationally bestselling author, and a world-renowned expert on change, influence, and consumer behavior. Also a leader in how products, ideas, and behaviors catch on, Jonah joins the show today to share insights from his most recent book, The Catalyst, including how to start influencing and stop manipulating your customers.

Listen in as he explains why persuasion is so hard and why simply telling people the facts is not always enough. You’ll learn the importance of giving your customers and employees a choice instead of telling them what to do, the key to negotiation, and what it takes to get your customers to persuade themselves.

Learn how to start influencing and stop manipulating your customers with @j1berger, author of THE CATALYST. Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The difference between manipulation and influence.

- Why persuasion is so difficult.

- The key to negotiation.

- The importance of giving your customers a choice.

- How to get your customers to persuade themselves.

Key Resources for Jonah Berger:

- Connect with Jonah Berger: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Amazon: The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind

- Kindle: The Catalyst

- Audiobook: The Catalyst

- Audio CD: The Catalyst

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley.I know most of you are interested in influence, persuasion, behavioral science, and related topics. That means today’s guest is someone you’ll really enjoy hearing from. Wharton Professor Jonah Berger both conducts research and writes about why some products catch on, why others don’t, what drives word of mouth, and a lot more. He’s the author of two previous bestselling books, Contagious and Invisible Influence. He’s helped organizations like Apple, Google, and Nike make their products catch on and even helped the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation improve its messaging. He has a brand new book out, The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind. Welcome back to the show, Jonah.Jonah Berger: Thanks so much for having me back.Roger Dooley: Great. Jonah, I know our listeners are interested in being more persuasive. The title of this show is based on my first book that was about 100 ways to be more persuasive using influence science. So the theme of your book is great, but I’m going to do something sort of stranger to start off. I’m going to quote a three-star Amazon review of your book, and I was surprised to find any reviews at all because when we’re speaking right now the book has not yet been released. But, apparently, a few copies were released to Amazon Vine reviewers.Roger Dooley: I’m not going to read the whole review, just the last two sentences. This is going to surprise our listeners, but it is not all that complimentary except, well, maybe it is in a way. So here we go. That review finished with, “This is basically a book of tricks to get unsuspecting, goodhearted people to do what you want and to think how you want them to think. I imagine it would be an excellent book for salespeople of any sort, whether we are talking peddlers, politicians, or phonies of any ilk.” It’s really a form of praise I suppose. This reviewer thinks your ideas work and doesn’t want people using them to manipulate others. But I’m guessing, Jonah, you didn’t write this book with manipulation in mind, did you?Jonah Berger: No, I did not. It’s never fun to get a negative review, but in this case, it’s not terrible.Roger Dooley: Well, Jonah, there is research showing that too many good reviews actually hurt sales and that there is sort of a sweet spot, which on a scale of five, would be somewhere around 4.5, where the scores are good enough that people think it’s a great product but not so good that they find the scores incredible. So maybe this is something that’s going to get you to that perfect 4.5 rating.

Jonah Berger: I hope that is the case. While I agree that tools can be used for negative, they can also be used for positive. I really wrote this book because I think so many people have something they want to change, and we often try so hard and we often fail. So I hope to figure out a way to help more people change the world for good.

Roger Dooley: Great. What the theme of the book is, first of all, persuasion tasks tend to be difficult, trying to get people to change their minds, how to change a company culture, getting a person with one political viewpoint to listen to another viewpoint, even getting your kids to eat spinach maybe. Why is persuasion so difficult? Why does not simply informing people, giving them facts, giving them basically proven information, why doesn’t that work very well?

Jonah Berger: Yeah. We all have something we want to change. We might want to change our boss’s mind. We might want to change an organization. We might want to change a customer or client’s mind. We might want to change an entire industry, or we might just want to get our kids to eat spinach, as you said. But change is often really hard. Often, we push and we push and we push. So the key question of the book is could there be a better way? I think when often we try to change, as you alluded to, we often think doing some version of pushing will work. “If I just send them more information. If I just provide more facts, more figures, more reasons, I just make one more phone call, and make one more presentation, and just tell people why they should do something, they’ll come around.”

Jonah Berger: I think that intuition makes a lot of sense. In the physical world, if there’s a chair that’s in your office and you want to move it, pushing it is usually a good way to go. You push the chair, the chair moves in the direction that you want it to go. But in the social world, there’s one problem, which is when you push people, they don’t just go along, they often push back.

Jonah Berger: So if pushing doesn’t work, what does? So I think this requires a subtle but important shift. Rather than asking, “Hey, what could I do to get someone to change?” Instead, ask a slightly different question, which is, “Why hasn’t that person changed already? What are the barriers or obstacles that are preventing change, and how can we mitigate them?” So that’s what the book is all about. It lays out five common barriers that come up again and again, whether we’re trying to change minds or drive action. It talks about what those barriers are and how we can create change by negating them.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. Jonah, you probably do a lot of interviews over the course of launching this book, but I am probably the only interviewer whose undergrad degree is in chemical engineering. So, I’m going to ask you about the title, The Catalyst.

Jonah Berger: Please do.

Roger Dooley: A catalyst has a specific meaning in chemistry, but I’m sure you can explain that concept in a more elegant way than I can, which will probably end up being really technical and convoluted.

Jonah Berger: I think your way’s probably just as good as mine, but I think we have a lay notion of what a catalyst is. A catalyst is someone who changes something. But in chemistry, a catalyst means something very specific, which is, as you and some of your listeners may be well aware, change in chemistry is very hard. It takes thousands, if not millions of years for coal and carbon to turn into diamonds, old plant matter to turn into oil, whatever it might be. So obviously, chemists want change to happen faster than that, so they use a special set of substances to get change happen faster and easier. These substances do everything from clean our car’s engine to clean the grime off our contact lenses.

Jonah Berger: But most interestingly is the way these substances work. Most change in chemistry requires temperature or pressure. You want to get something to change, you up the temperature or you increase the pressure. I like talking about popcorn kernels. If you think about a popcorn kernel, it doesn’t just magically turn into popcorn. You have to heat it up. You have to either put it on the stove and heat it up. You have to put it in the microwave and heat it up. Your heat, that increases the temperature and the pressure. Eventually, that popcorn kernel pops and it turns into edible popcorn. Same thing in Chemistry, add more temperature, add more pressure, change happens.

Jonah Berger: But what’s neat about these special substances is that they don’t add temperature and they don’t add pressure. What they do is they find an alternate path to create chemical change. They create the same change, not by pushing harder, but by removing the barrier of change, by allowing change to happen with less energy. As you probably guessed, these substances are called catalysts. Not only have they won multiple Nobel Prizes and changed everything from the food we eat to the lives we live, but the same approach is really useful in the social world, not pushing harder, not more temperature and more pressure, but by being a catalyst, by lowering those barriers and finding an alternate and easier path to change.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So, give an example of lowering those barriers and how it doesn’t always take more pressure. Because, I think, really in any sales process, this is a natural tendency in any persuasion process, you want to push harder. But catalysts, of course, don’t work that way. That’s the magic. I think that the chemists who’ve discovered these catalysts probably thought they were magical to begin with. Because imagine you have this kettle of popcorn sitting there and yeah, you could heat it up and eventually, it’d start popping. But instead, you throw in some platinum BBs or something and suddenly, the kernels start popping themselves. That’s almost what happens in chemistry. So, what’s an example from the real world of this?

Jonah Berger: Yeah, sure. So, in the book, I talk about five barriers. I talk about reactance, endowment, distance, uncertainty, and corroborating evidence. Put them together, they spell an acronym, which is REDUCE. That’s exactly what catalysts do, they reduce barriers. So just to start with the first one, I think a key barrier we often face is reacts. When we try to get people to do something, they push back. It’s almost like people have this innate anti-persuasion radar when incoming projectiles come in, just like an anti-missile defense system.

Jonah Berger: When someone senses that someone’s trying to persuade them, whether through email, over the telephone, or presentation, whatever it might be, their radar goes up and they shoot down those projectiles. They avoid or ignore them. A commercial comes on the television or an email comes in that you’re not interested in, it’s a sales pitch, you delete it, you do something else. Or even worse, they start counter arguing. Yes, they’re sitting there. Yes, they look like they’re paying attention. But rather than just paying attention, they’re thinking of all the reasons why what you’re suggesting is wrong.

Jonah Berger: So obviously, if they’re going to think about all the reasons why you’re suggesting is wrong, it’s going to be really hard to change their mind. People like feeling like they’re in control. We love feeling like we’re in control of our destiny. When someone else impinges on that, we push back. There’s a great story I tell in the book actually around Tide Pods. Many of your listeners made these Tide Pods. They’re these little concentrated liquid Tide that isn’t a little sort of capsule or container that essentially rather than having to figure out how much detergent to put in, you just drop them in the washing machine and they work really well.

Jonah Berger: So Tide spent forever introduced these things. They spend a bunch of money on marketing. They were hoping it would take a big share of the laundry detergent market. They launched it, did okay, but then there was one problem which is that people were eating them. So you’re sitting there going, “Well, why would anyone eat liquid detergent? They must be crazy.” So there was a funny video online, and then people were challenging each other. Suddenly, teens were doing this thing called the Tide Pod challenge, which they were challenging each other to eat Tide Pods.

Jonah Berger: So Tide is in this situation trying to figure out what to do. They do what most companies do. They declare, they send a PR thing that says, “Don’t eat Tide Pods. You should never eat Tide Pods.” In case that’s not enough, they hire a celebrity, Rob Gronkowski of New England Patriots fame, who shoots this funny video saying, “Look, never eat Tide Pods. Terrible idea. No, no, no, don’t eat Tide Pods.”

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I guess to interrupt there. That is really not all that bad of a strategy when you first glance at it. I mean, first of all, you do the sort of obligatory informative PSA, but then you enlist somebody who is well-known and popular and you make it kind of amusing and funny but still get that basic message there. So I think a typical PR person might say, “Well, yeah. Hey, they’re doing it right?”

Jonah Berger: Yeah. Notice, by the way, we do the same thing all the time. We say, “Hey…” We don’t want someone not to do something, we want them to do something. “Let me tell you why you should do something.” We think that’s enough. But in Tide’s case and in our cases, it backfires. In Tide’s case, after they made that proclamation, “Don’t eat Tide Pods,” searches for Tide Pods went up over 400%. Visits to Poison Control went up multiple hundreds of percent as well. Essentially, a warning became a recommendation telling people not to do something became a recommendation to do that exact thing.

Jonah Berger: Same thing in our situation. We tell people to do something even if it’s something they might have wanted to do in the first place. We say, “Hey, you should adopt this new product or service.” Even if someone was thinking about it, when we tell them to, now they’re not sure if the reason they want to is because they want to or we wanted them to. Because of that, they’re less likely to go along. So to figure out how to solve that problem, we need to allow for autonomy to reduce reactance.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So I think maybe your example in book about teen smoking would kind of be in that same vein because we know that people have been trying for years to communicate with teens and smokers of all ages the dangers of smoking. But it hasn’t been all that effective. But, what does seem to work?

Jonah Berger: Yeah. So I’ll give you one example. In the book, I talk about four ways to reduce reactance, but I’ll share one here and that’s very simply called providing a menu. So we think about that quintessential situation. We’re trying to change someone’s mind. We were pitching a client, for example, on a certain strategy or solution. We’re trying to change a customer’s behavior and get them to adopt our product or our service. When we give people one option and we tell them how great it is, they often spend a lot of time sitting there thinking about all the reasons that’s wrong with it.

Jonah Berger: So if we’re in that meeting and we’re telling you, “Oh my God, this new service is going to solve all your problems.” The client’s not sitting there going, “Oh great, this is going to be amazing.” They’re sitting there going, “Well, of course, you’re going to tell me this service is going to be amazing. You’re the one that made this service. You would never tell me it’s not amazing. How do I know I can actually trust you?” Thinking about all the reasons why what you’re saying is wrong.

Jonah Berger: So rather than give people one option, give them multiple. Give them at least two. It suddenly shifts the role that that listener’s in. Rather than sitting there counterarguing, thinking about all the reasons why they don’t like what you’re suggesting, when you gave them two options, now by nature they’re going, “Well, which of those do I like more?” By doing that, they’re spending less time thinking about why they’re bad and more time figuring out which of them they like, which is going to make them more likely to pick one at the end of the day.

Jonah Berger: I talked to some smart consultants who do this all the time. They say, “Look, you give people one option, they say no. Give them two or three, maybe don’t pick exactly the one you wanted, but at least they pick one rather than saying no thanks.” So in some sense, it’s choice but it’s guided choice. You’re not giving people infinite choice, and you’re not giving them no choice. You’re giving them a small set of selected choices. You’re choosing the choice set and allowing them to choose from that choice set. You’re giving them that autonomy, that freedom to choose, but shaping or guiding that journey.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Jonah, you teach at an elite school. Lately, we’ve been hearing all about the folks who were cheating to get into schools by either faking exam results, or bribing officials, and so on. So college admissions is a pretty big deal in the United States, especially compared to at least some other countries. You have an example in the book of a test prep company that found its student customers were not really willing to do the hard work required, at least when they first talked to them. I guess that’s not totally surprising because what high-school-age student really enjoys buckling down and studying stuff to pass a test?

Roger Dooley: But at the same time, it’s an important thing because it’s an important life decision or a life moment for people. If they do want to get into one of those schools that requires a high test scores, then hey, they got to perform. So, how did this particular test prep company address that? How did they say, “Okay, we’ve got to help these students reframe their thinking as they really decide they’re going to put the effort in”?

Jonah Berger: Yeah. While the example’s about a test prep company, it’s an example that many of us face all the time. How do we get people to do something they don’t want to do? So in the test prep company’s case, “How do we get students to study more?” As we’ve discussed, the tendency in that situation is to push, to pressure, to provide information or reasons. “You should study at least 30 hours a week or you’re not going to get a good score on the exam. If you want to get into this school, you need to do this.” We think if we tell people what they should do, they’ll do it.

Jonah Berger: But I talked to a leader, a co-founder of a test prep company in Washington D.C. and as we can guess, he said that often doesn’t work. When you tell students, “You need to study much more that you’re studying,” he finds one of two things happen. Either they say no way, or they quit and they don’t come back. So he was trying to figure out an alternate way to get them to come around. What he realized was asking was better than telling. Questions were better than statements. Rather than telling people, “Hey, this is how much you need to study,” one time he tried a slightly different tactic. He said, “Look, I’m going to start by asking questions.”

Jonah Berger: With this new group of students, rather than telling them, “Hey, you need to study more,” he said, “Let me start in a different place. Why are you guys here?” Everybody said, “Oh, well we’re here because we want to get into the best programs in the United States in the world.” “Okay, great. What does it take to get into those programs?” “Well, maybe you need this test score. We’re not really sure.” So they start a conversation about what it takes to get into those programs. Then, he said, “Well, what kind of scores do you need?” Then they had a conversation about that and then eventually asked, “Okay. Well, then how much do you think you need to study to get those scores?” What he’s doing is rather than telling them what they need to do, he’s asking a set of questions that guide that journey.

Jonah Berger: So at the end when the conversation goes, “Oh, well you’re going to need to study this much to get into those places,” students have committed to the conclusion. They’ve already said they want to get into those places. They’ve already said that’s the reason they’re there. So it’s much harder to back down. So he’s found this not only increases how many students stick with the program but their performance as well. Same situation with a boss. I was talking to a guy who was trying to get his employees to work harder. He could tell them to work harder all they wanted, they didn’t want to do it. So instead in a meeting, he said, “Look, what kind of company do we want to be? Do we want to be a good company or a great company?” Now, again, notice what he’s doing. He’s not telling people, “You need to do this.” He’s saying, “What kind of company do we want to be?”

Jonah Berger: Everyone says, “Oh, we’re going to be a great company, great company.” Then he goes, “Okay, what do you think we need to do to get there?” Subtly, by asking questions, he’s again shifting their role. Rather than sitting there listening, thinking about all the reasons why they don’t want to do what he’s suggesting, they’re participating. If they’re participating and they suggest something, “Well, here’s what we need to do to get to that place,” well now it’s their suggestion and they’re much more likely to go along with it later. They’ve committed to a conclusion and so it’s much harder for them to diverge from that path. So rather than pushing, or pressuring, or telling people what they should do, questions is a great way to allow for autonomy.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). That seems like a strategy that would work in a lot of situations where you’re sort of letting people persuade themselves. If you try and persuade them, you’re going to activate what you call their anti-persuasion radar. But when they’re simply sort of thinking through it themselves, those conclusions are harder to dismiss or disagree with.

Jonah Berger: That’s exactly right. Notice getting them to persuade themselves may seem like magic. When we hear that, we go, “Okay, sure. That sounds like a great idea. I’ll just come back two weeks later and they’ll have persuaded themselves.” It doesn’t mean completely hands-off. But it doesn’t also mean completely hands-on. It means shaping the journey but not prescribing the journey. It means shaping the path and guiding the choices but not telling them what to do. Again, it’s sort of that idea of bounded choice or bounded questions shaping that journey but allowing them within that space to come to the conclusion you wanted them to come to already. Guiding but not forcing.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). While we’re on the anti-persuasion radar piece, we’ve had former hostage negotiator Chris Voss on the show, and he wrote a really good book, Never Split the Difference, which I recommend. You talk about hostage negotiation as well in the book and as an example of a persuasive process where, in that situation, you can’t just make demands yourself or dive into an argument. That’s simply not going to work. You have sort of a stair-step approach. Explain how that works.

Jonah Berger: Yeah. Again, most of us are not hostage negotiators. Most of us hope didn’t ever be in a situation where you have to negotiate for hostages. But the same issues, the same ideas come up in whatever we’re trying to persuade people to do. We may not be trying to persuade people to come out with their hands up. We may be not trying to persuade someone who was thinking about commit suicide to not do it, but we have the same issues. If we jump straight to persuasion, it’s not going to work. Good hostage negotiators say this all the time. But the first step most novice negotiators want to do, they want to jump right away to, “Hey, come out with your hands up. Do exactly what I want.” They want to jump to persuasion, but you can’t start with persuasion.

Jonah Berger: No one’s going to be persuaded unless they feel like they can trust and understand you and why you’re doing what you’re doing. So great negotiators really start with understanding. They start by figuring out, “Who is this person that I’m trying to persuade? Where are they? Why aren’t they doing what we want them to do in the first place? How can I use that knowledge or information, again, to shape that path or guide that journey?” They’re not starting by telling someone what to do. They’re starting by figuring out, “Well, why is that person here in the first place?”

Jonah Berger: I think a good analogy if you think about weeding a garden, you tear the top off the weeds. That’s the easiest way to weed the garden. Got all these weeds, let’s rip off the top. It’ll be done. But the problem with ripping the top off the weeds is they just grow back. If you don’t solve the underlying problem, if you don’t find that root, you’re not going to be very successful. So the same is true of hostage negotiators. Good negotiators start by finding the root. They start with understanding. They start by figuring out why the person is in that situation and then they figured out how to solve it.

Jonah Berger: There’s a great story I tell in the book of a certain negotiator who’s trying to get a guy not to commit suicide. This guy has lost his job. He has an insurance policy taken out himself. He thinks the only way to provide for his family is to cash in this insurance policy. He kills himself, his family will have the money they need to live. The tendency in this situation is just to come in and just say, “Hey, it’s not going to work out. You kill yourself, the insurance policy’s not going to pay out. You should just skip doing this.” The tendency’s to jump straight to persuasion, but obviously, that’s not going to work. If you’ve got someone like that in a fragile state, that’s not going to change their mind.

Jonah Berger: So, what the guy did is he started very differently. First, he introduced himself. He said, “Hey, how can I help you? What do you need?” He starts having a conversation. And as part of that conversation, he says, “Tell me why you’re here.” The guy says, “Oh, I’m going to kill myself because I want to provide for my family.” He says, “Okay, well tell me about your family.” The guy starts talking about his family, starts talking about his kids. He says, “Okay, well tell me about your kids.” The guy says, “Okay. I’ve got these two great young boys. I’m trying to raise them to be good young man. I take them fishing. I do all these things.” So they have a real conversation.

Jonah Berger: Eventually, after they’ve had some of these conversations, negotiator says, “Well if you kill yourself today, your son is going to lose the best friend they’ve ever had.” What they’ve done right there is really cleverly put the person in a situation, put the person in a situation where they’ve got to persuade themselves. That person has said, “Hey, I care about my kids. I care about being there for my kids.” Now, the negotiators put them in a situation. They go, “God, the best way for me to help my kids is to not do what I was going to do initially but to come around and actually surrender,” which is what the guy did. He’s taken that option of killing himself off the table. He’s helped him realize, not by persuading him, but by saying, “Hey, what do you care about? I’m going to show you how the best way to get to what you care about is actually doing what I wanted you to do in the first place.” Encouraging that person to come around by using their information and helping guide that journey.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Trust is part of that. I think trust comes up in about every second conversation here on the show and it’s simply because it is such an important factor in any kind of persuasive process. But when you rush right into persuasion, you don’t have a chance to build that trust. In your example of a person that’s trying to commit suicide, then part of that exchanging information and talking about the kids and whatnot, that builds trust. Presumably, the individual who was trying to diffuse the situation did not do anything to reduce that trust, lunge for him, or do anything that would cause the person to distrust him. Even in less tense situations, just in any kind of business interaction, just taking the time to get to know each other and build some of that trust gets it out of a persuasion mode and into more of a cooperation mode.

Jonah Berger: Yeah. And very similar to what we talked about at the beginning with that negative review action. Why are negative reviews helpful? Well, they’re diagnostic because they suggest that their reviews are real. If one out of every 10 reviews is negative, it’s like this isn’t just a carefully selected set of people who all think it’s perfect. It’s actual people’s feelings about these things. So the same thing is true with a client or a customer. If every time you ask them what they need and they tell you and every time you suggest that your thing is the best, that’s not going to work out in the longterm. Because eventually, they’re going to go, “Of course, you’re going to say your thing is the best.” But if once out of every 10 times you say, “Actually, you know what? I’m not the best person to help you.”

Jonah Berger: I do this often in consulting calls. I get a lot of people that reach out and say, “Hey, can you help us with this project?” Some of them I say, “Yeah. I can help you with this project.” But I also say, “Look, if I’m not the best fit, I’ll let you know.” Once in a while, I’ll say, “Look, I’m not the best fit for what you need, the expertise you need, the situation you need. Actually, here’s another person that’s better.” I often find those people that I refer them to someone else, actually come back later for something else because they trust me. They know that I’m not going to just do what’s in my best interest, I’m going to do what’s in their best interest. And because of that, they’re more willing to give me business in the longterm.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. That kind of ties into research too that shows that if you are making a persuasive argument about a product, for example, that you are more persuasive if you point out a flaw in the product or a situation where it won’t work because it adds credibility to the rest of the pitch. I that’s such an overlooked point because nobody ever wants to say anything bad about their product, or their service, or anything else. It’s like, “It’s just great. It’s always great. It’s great for everybody.” But when you are more honest and do point out those things, that builds trust.

Jonah Berger: Certainly.

Roger Dooley: So Jonah, a lot of our listeners are familiar with the endowment effect, the coffee mug that you own is worth more than the same identical mug that somebody else is selling. But most of us aren’t selling coffee mugs. What are some examples of the endowment effect and how it can hinder persuasion or change in terms that aren’t quite so monetary as that?

Jonah Berger: Yeah. I mean, the main idea I take away from research on the endowment effect and work in that area is findings on the status quo bias, which is that we tend to be attached to things that we’re doing already. We’re attached to the products that we’re using. We’re attached to the services we know. We go back to the same vacation destinations, the same restaurants. We use this same service providers again and again because they feel safe. We become attached to the old, which is great for the old stuff. It’s great for the status quo, but it’s terrible for change. Because if people are attached to what they’re doing already, they’re not doing that new thing that we hope they’ll do.

Jonah Berger: So if we’re in a new service provider, we’re trying to get people to switch to a new product, how do we do that? So part of what we need to do is make them realize that sticking with the status quo isn’t costless. Often people think, “Oh, look, I’ll do what I’ve already been doing and there won’t be any cost to sticking with it.: There are some costs to that old thing. It’s not going to be great forever. It’s not going to work forever. Here’s some problems with the old, but also making the new thing feel less risky. Not only do people have the status quo bias, but they’re also neophobic. They’re scared of new things.

Jonah Berger: Part of the reason is really about an uncertainty. Not only are there switching costs, there’s always time, or money, or effort, or energy to do something new. If I buy a new product, I have to pay for it. If I install a new service, a new system, I have to put time and effort into doing it. But that new thing is always uncertain. “Sure, you say it’s going to be better, but how do I actually know if it’s going to be better? Again, if you’re saying it, well, of course, you’d say it. But how do I actually know?”

Jonah Berger: So what really good change agents do, what really good catalysts do is they lower the barrier to trial. They figured out a way to allow people to experience the offering and lower those upfront costs. So think about a company like Dropbox, for example. Rather than saying, “Hey, you have to pay to use our service right off the bat,” they reduce that barrier by saying, “You can have two gigabytes of storage for free.” Now, you’d say, “Hold on. How can you build a business about giving away things for free?” Every child who’s ever had a lemonade stand knows you can’t make money by giving things away for free, but they don’t give everything away for free. They give some away for free and encourage you to upgrade. They use a term that many of your listeners are probably familiar with, the idea of freemium.

Jonah Berger: There’s a free version of Dropbox, up to two gigabytes, but there’s also a premium version. Same with things like Skype, and LinkedIn, and many different softwares and service models. You give away something for free initially, but you allow people to see that there’s a better version and encourage them to upgrade. What that does is it says, “Look, don’t trust me that Dropbox is good. Of course, I’m Dropbox, I’ll say it’s good. Check it out yourself. It’s completely free to use. And by the way, if eventually you run out of two gigabytes of storage, you’re going to be willing to upgrade to that better version. You’ll be willing to pay me money to do it because you’ve convinced yourself it’s good.” Again, it’s the idea of sort of self-persuasion, getting people to persuade themselves.

Jonah Berger: I’m not telling them how great it is. I’m lowering that barrier to trial. It’s not just freemium. Think about test drives in a car. Does the same sort of thing. If I said, “Hey, you want a new car? Great, give me $30,000 and then I’ll let you experience it.” You’d say, “No way.” But that’s what most of us do most of the time with our product and services. We demand the money, the cost, the time, and the effort, and energy upfront and only later do people get the potential benefit, which they’re uncertain about. So what smart companies, smart catalyst, smart change agents do is they lower that barrier. They give a test drive, say, “Hey, look, come in. Check out the car.” It still costs the same amount to buy it, but it lowers that upfront cost and making people much more comfortable checking it out and as a result, buying it.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). In my book, FRICTION, I talk about Evernote who uses the freemium strategy because it made it really easy to onboard new users. They still provide huge value to most of their subscribers for free. Most of their people who use Evernote don’t pay for it, but enough of them do pay for it. I’m one of those. It’s ended up being a very profitable business model for them. But to tell me upfront, “Well, you should really buy this product because then you can store stuff in it.” I probably would not have signed up for a subscription right out of the gate. It looked a little bit complicated and it would not have been a great value proposition. But once I was using it, then it was, “Oh hey, okay, this actually really works well and I want to take it to the next level.”

Roger Dooley: So that’s great. I guess another endowment effect would be Brexit. The early proponents of Brexit showed that staying had a cost, that doing nothing, staying in the EU meant were paying a whole bunch of money to bureaucrats, perhaps, or this is the way they framed it, paying a bunch of money to EU bureaucrats instead of using them for valuable purposes within the U.K. like healthcare and such.

Jonah Berger: Yeah. We talk about this a bit in the book, but this notion of sort of take something back suggests that the new thing isn’t actually scary and new. It’s actually a prior thing we’ve been doing previously, but this is going back to it, which makes people feel much more comfortable in doing something that is actually new, in this case, Brexit, but saying, “Hey, we need to take back what we had before.” I think with freemium, it’s a great strategy, but it’s not just about giving things away for free. It’s really about lowering the barrier to trial. Even the physical goods, how can we allow people an experience? When we give people a chance to see what we think is great, they’ll experience it themselves and if they like it more, they’ll purchase it.

Jonah Berger: If we’re a doctor, if we’re a hospital system, if we have a physical good, we may say, “Well, it costs a lot of money to give something away for free.” That’s fine. You don’t have to give it away for free. But how can you allow people to experience the value so they’ll be willing to pay for the full version later?

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I totally agree with that. If you look at some of the tremendous growth stories in recent memory, things like Instagram, and WhatsApp, and so on, they were free products and they were also very easy to get new users onboard. That was really a key. They did some other smart things as well to allow them to grow virally. But it’s a business model may not work for everyone. But, boy, in a lot of cases, it’s so much better to let people experience the product and to also achieve critical mass because none of those products would succeed if they didn’t reach critical mass and get the network effect kicking in, particularly in those cases.

Jonah Berger: Definitely. Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So I would love to go through all of the elements of the REDUCE framework, but we won’t have time for that today. So I would encourage everyone to actually buy The Catalyst, unless, of course, they are peddlers, politicians, or phoneys in which case, they shouldn’t. But I know that our listeners are none of those things and will find it a very powerful book to enhance their persuasive skills. So let me remind everyone that today we are speaking with a professor and researcher, Jonah Berger, author of the new book, The Catalyst, How to Change Anyone’s Mind. Jonah, how can people find you and your ideas?

Jonah Berger: Sure. So the book is available wherever books are sold. So Amazon, Barnes & Noble, wherever you like. You can find me on my website, which is just Jonah, J-O-N-A-H, Berger, B-E-R-G-E-R.com, or I’m also on LinkedIn and on Twitter @j1berger.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to all of those places and to any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Jonah, thanks for being on the show. I really enjoyed The Catalyst, and I’ll look forward to referring back to it in the future.

Jonah Berger: Thanks so much for having me back.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.