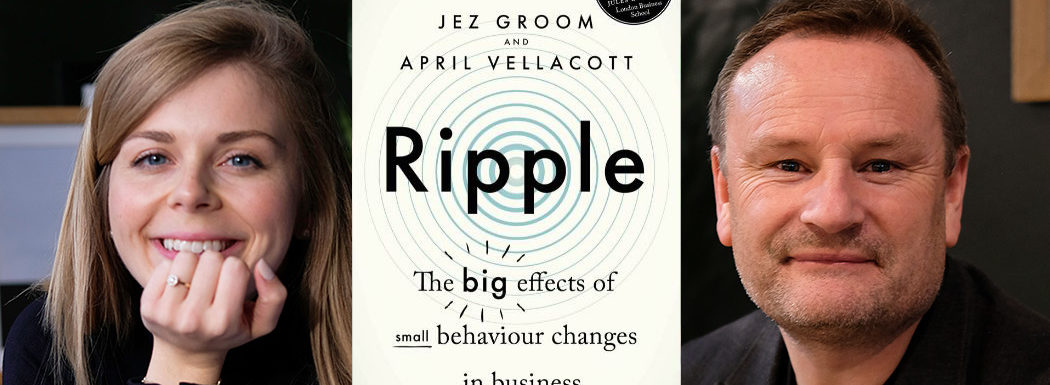

Jez Groom has been practicing behavioral science for over ten years, working with some of the biggest organizations around the world. In 2016 he founded Cowry Consulting, the leading behavioral economics consultancy, and is currently a visiting fellow of Behavioural Science at City University.

Jez Groom has been practicing behavioral science for over ten years, working with some of the biggest organizations around the world. In 2016 he founded Cowry Consulting, the leading behavioral economics consultancy, and is currently a visiting fellow of Behavioural Science at City University.

April Vellacott has been studying the field of human behavior for nearly a decade, and holds degrees in Psychology and Behavior Change. As a behavioral consultant at Cowry Consulting, she helps global clients apply behavioral science in their organizations.

Together, Jez and April are the authors of the new book, Ripple: The big effects of small behaviour changes in business, and they join the show today to share how small behavior changes can have wide-reaching effects. Listen as they give real-life examples of how nudge theory has had massive impacts on outcomes, why friction is sometimes a good thing, and how behavioral principles can benefit any business.

Learn how small behavior changes can have wide-reaching effects in the real world with Jez Groom and April Vellacott, authors of RIPPLE. Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How small changes can have massive impacts on the world.

- Why friction is sometimes an important part of the process.

- What anchoring is and why it’s important.

- How design plays a role in nudge theory.

- Why there is a balance between too much effort and too little effort in the outcome.

- How behavioral principles can benefit any business.

Key Resources for Jez Groom and April Vellacott:

- Amazon: Ripple: The big effects of small behaviour changes in business

- Amazon UK: Ripple: The big effects of small behaviour changes in business

- Kindle: Ripple

- Ripple Companion Hub

- www.Harriman-House.com/Ripple

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence, I’m Roger Dooley. We’ve got not one but two guests today, both experts in behavior change for businesses. Jez Groom has been practicing behavior science for more than 10 years and was the Co-Founder of Engine Decisions at Ogilvy Change, where he held the title of Chief Choice Architect. Today, he’s the Founder of Cowry Consulting and honorary research fellow in the Department of Psychology at City University. April Vellacott is a behavioral consultant at Cowry and helps clients around the world apply behavioral science. Together, they are the authors of the new book, Ripple: The Big Effects of Small Behaviour Changes in Business.Welcome to the show, April and Jez.

April Vellacott: Thanks for having us.

Jez Groom: Thank you.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, so April you studied psychology as an undergrad and earned a masters in behavior change. But Jez, you studied biochemistry. How did you end up in so many cool behavioral science roles?

Jez Groom: Yeah. That’s a good question, a question I get asked quite a lot. My background was in advertising so I worked in media and marketing, and then kind of my paths crossed with Rory Sutherland, who I know is one of your previous podcast interviewees. And the pair of us came together to create the behavioral science practice at Ogilvy, which started at first to look at how affective the advertising process. But I quickly got more interested in things that were non-advertising and got really, really enthused.

And that was kind of when I broke away and thought, actually there’s a lot more problems can be solved with behavioral science than simply communication ones. So yeah, created Cowry. I mean, the other reason was I really did want to go back to school and college and get my psychology degree. I think it was a missed opportunity. But unfortunately at the time, I had three small children and my wife thought maybe that wasn’t a good idea.

I went straight into business and essentially practically applied it. I’ve come full circle, as you mentioned earlier. I’m now also aligned with the faculty at City, but I don’t have a formal degree.

Roger Dooley: Right. No, it’s great. And I think that any kind of scientific or engineering background can be pretty useful in this field because it gets you focused on research and evidence as opposed to opinions, which is really, I think, what applying behavioral science is all about. It’s really all about the proof, the evidence, the numbers and so on.

Yeah, and one other thing, Jez. People have called you Yoda, and I guess can explain that. But more importantly, how do you use that when you’re presenting?

Jez Groom: Yeah, I mean, it’s coming to, I suppose, a pratfall effect. One of the things that I think Adam Ferrier, he’s a consumer psychologist in Australia, founder of a really interesting business called Thinkerbell. And he came and did a conference, so it was one of the early Nudgestock conferences that we did, flew him over from Australia. And he talked about this phenomenon called pratfall, which is the world isn’t perfect and our brains are very, very good at identifying kind of perfectness and seeing actually what we really want is authenticity and maybe things that are imperfect and those things are more sort of more motivating. So people prefer kind of rough cookies or people that maybe aren’t so smooth. Yeah, so I used to introduce myself as Yoda because I’m quite short. So I’m 5’5. I got to the age of 13, didn’t really grow in height and I’m so pleased. I’ve got three teenage boys and they are all taller than me, and I’m so pleased. So I think the combination of behavioral science skills to essentially nudge people combined with a diminutive height, I mean that, yeah, I earned the nickname of Yoda. I always did caveat it and say, “I didn’t think and I don’t think my ears are as hairy as Yoda’s.” For sure.

Roger Dooley: Just give it a few years Jez, it’ll happen. Trust me. It’s great because people think they have to be perfect and polished. And what you’re saying is, sometimes it’s okay to show a little bit of vulnerability, although preferably not in that exact thing that you’re supposed to be the expert in, but rather show it in some other way.

Jez Groom: Yeah. Yeah, a pratfall in a core competence is maybe not the best.

April Vellacott: It’s funny that you mentioned that actually, roger because I was talking to my sister on the phone earlier from isolation of course, because we’re on lockdown in the UK, and she was talking about, she’s she’s applying for jobs right now from lockdown, which is a bit tricky. She’s doing everything over Skype and Zoom. And she was telling me, she goes, “Why is that her presentation for this job was too perfect.” So I tell her that she should try and craft some of this pratfall effect into her interview. But we were struggling to think of something she could do over Zoom that wouldn’t undermine her ability to actually do the job.

Roger Dooley: I think maybe a cat walking in front of the camera for a second might do that, if she happens to have a cat.

April Vellacott: That’s a good idea.

Roger Dooley: Although, she should not do what a one small sort of a low level politician did here in the States. I think in California, where he was in a council meeting of some kind and his cat came on screen and he physically picked the cat up and chucked it into the corner. And you heard a yowl as the cat hit and now he’s under pressure to resign for animal cruelty. So you got to do that just right. Sorry. Sorry. I really enjoyed Ripple. It was a fun, easy read. The subtitle reminds me of The small BIG by Cialdini, Martin and Goldstein. But I think the key thing there, one of the most important things about behavioral science is that small, often inexpensive interventions can have an outsized impact. And there’s still a lot of people in business who just don’t get how effective behavioral science can be. Jez, I’m curious, you took an unusual approach to convince the management team at Ogilvy about the importance and effectiveness of behavioral science. So why don’t you tell the rabbit story?

Jez Groom: Yeah, so I think one of the interesting things is that I don’t think people believe in behavioral science until they experience it. So I think some of the early work done by Ariely, although it was very playful, I think really dramatized some of these biases we have in our minds and these shortcuts and processes. And yeah, when we were Ogilvy, we did four experiments to launch the practice and I’ll talk about one of them, which was kind of my favorite. Just imagine a scenario you’ve got, I don’t know, 30 relatively to very highly paid advertising executives who are very conscious. These guys and girls are cool, they’re smart, they’re advertising and they don’t want to look stupid. And we did an experiment to try and get them to behave like a rabbit, to bounce around like a bunny.

So what we did was we had a control group and essentially they were told to watch a video. It like a child’s video, something my children have seen and there was a song in it. I’m not going to try and sing it too well, but essentially it says, “See the little bunny sleeping on the floor.” And then he says, “Wake up little bunnies.” And you have to essentially jump up and then bounce around like a bunny, which is great fun for a three year old, less so for 33 year old. And so in the control group, we just sort of said, “Look, watch the video and read these instructions,” which said, just play along with actions. Unbeknownst to them, we videoed them. And of course they just sat around the room and were like, yeah, I’m not going to do that. And you could see them talking to each other saying, “Yeah, we’re not going to do this are we?” Because they didn’t know that they were be watched.

And then we had another treatment group where we had about 20 people, myself and also the chief executive and the group planning director were in on it. So essentially I had some strong messengers and the other participants sort of followed my instructions. And I said, so if everybody could lay down on the floor, which they did, which again is quite odd in a business environment. We all pretended to be asleep. And then as we got to wake the little bunnies, we all jumped up as in myself, the plan director and the CEO, and we started jumping around. And everybody followed, unbeknownst to them we had secret videos all around the room. And the great thing about it was, being in an ad agency, we managed to combine a film, which you can see at ripple-book.com. It was just essentially bringing these experiments to life.

And we showed this film in front of all their colleagues. So there was these 27 people that have been made to make relatively a little bit silly and change their behavior because they were following the messengers and joining them with the ingroup and heard. I think it’s when you do these experiments on site, in the environment and context in which people are working, that’s when you get believability. The amount of times that we’ve gone into businesses to say behavioral science really works, they go, “Yeah, I can see how it could work for that business. I can’t see how it’d work for my business, because we’re different. We’ve got different proposition and different challenges.” And then what we then do is a pilot study and we prove it works and they go, “God, this stuff really works.” And we go, “Yep. Yep, it does.” And then from then on, we can move on. But yeah, I think they’re trying to make it a little bit of fun at the start and certain business environments it’s relatively okay to do that. But yeah, we had a lot of fun at Ogilvy.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well I think you’re starting with the situation where most people are willing to acknowledge that other people are irrational actors, that they can be influenced by these nudges and things. But they themselves are not of course, which actually isn’t true, but I think that’s the bias you have to overcome in any kind of a business situation where you’re trying to tell me about the effectiveness of this. And they say, “I would never do that. I wouldn’t be influenced by that.” And that tends to make them doubt the effectiveness of it.

Jez Groom: Yeah. I mean, I don’t know April, if you’ve had any experiences. Certainly, I think you had an experiment with the sort of anchoring effect with academics, in your first lectures, I think.

April Vellacott: Yeah, for sure. I mean, you’re absolutely right, Roger, that once it’s been brought to life for you in a way that feels really relevant to you, then yeah, you just don’t believe it’s as true. It really brings it off the pages of a book and to the real world. So I did my undergraduate degree in psychology at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, and it was one of the most memorable moments of my degree, actually. And it just seemed like any other seminar, one morning and our lecturer put up this picture of our matriculation cards on the whiteboard and said, “I want you to all reach into your pocket and just write down the last two numbers of your matriculation card.” So we all did that. We all had really random numbers, so someone had 12, another one had 27, someone else had 98. And then they put up this picture of a bottle of wine on the screen and they asked us to write down how much we’d be willing to pay for that bottle of wine. And we got quite excited at this point because we were all students and we thought maybe we’re in with the chance of winning an expensive bottle of wine.

Roger Dooley: That’s right. The price is right. You’re the winner.

April Vellacott: So we all wrote down these prices that we were willing to pay and, we were probably quite stingy because we were students. And at that time, I was paying about four pounds per bottle of wine, not joking about that. And what was really interesting was the price that we were willing to pay for this bottle of wine was influenced by this completely unrelated number that we’d just written down. So that last two numbers of our matriculation number. And then they went on to explain, this principle that we all know called anchoring, which as you guys know, is where your judgments of value of something can be affected by the first piece of information that you’re exposed to. So I never really forgot that. And it’s those kind of ways that you bring it to life for the businesses that you work with, that as you say, really make some belief that well actually, if this applies to me, it must apply to colleagues and to our customers. And so there must be something interesting we can do here by applying painful science to make things better.

Roger Dooley: Well, sure, because I don’t think anybody would acknowledge that seeing a random two digit number would influence their estimate of the price of something. That’s a classic Ariely experiment.

Jez Groom: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: But I think as a demo, just to show people that yes, even you Mr. or Ms. rational actor have these really bizarre influences on your behavior. It’s really powerful. I’m curious, I assume that you’ve done these kinds of things at clients or potential clients and such. Have you ever had at one go awry on you where somehow the demonstration didn’t work at all?

April Vellacott: I mean, we actually did it, we did that very experiment. We tried to do the anchoring experiment in real time for one of our clients. What was it a couple of months ago, I think, Jez and I, and it didn’t quite work out. So we just kind of glossed over that and moved on quite quickly.

Roger Dooley: Well, you do it enough times, you’re going to get a random result that isn’t very good. And it could be too that these days, a lot of people have a read Predictably Irrational. They might be on guard for that kind of manipulation or even decide to, “I got a low number, I’m thinking to give a really high estimate for the value of that product.” But one of the things I really liked about the book was that you emphasize a do-it-yourself approach very explicitly in every chapter. A lot of books written by consultants are sort of demonstrating much they know how smart they are and how much should they can help your organization if you hire them. But I think here, and obviously, businesses can benefit from hiring an organization like yours, but for those businesses who can’t afford outside consultants or even can’t afford them for smaller projects, I mean, large businesses can’t afford to bring in outsiders on every single thing they do, there is so much practical advice in there about how to go about doing it. And so that, I really commend you for that. That’s makes it, I think, very useful for business of any size, whether it’s large or small.

Jez Groom: Yeah. I mean, it’s a really good point. And one of the things that myself and April wanted to do was to democratize behavioral science. And I think you mentioned Ariely. I think Ariely has been kind of a professor, I think, that especially bridge that gap between the business world. Obviously sits on a few startup boards as a behavioral officer. But quite a lot of the work seems to be written in a language in broader academia. It’s just impenetrable for anybody that isn’t sitting there doing a PhD to understand or engage with and then use. And then I think there’s quite a few behavioral scientists kind of in my network that does get frustrated or do get frustrated with that. Sometimes you say things like, “yeah, there’s this amazing principle that’s called primacy effects.” And the first impression that you have within a customer experience and because the rest of the experience. And you kind of go, “Okay, so that is first impressions count then.” And you kind of go, “Yeah.”

So it’s quite a lot of behavioral insights, kind of common sort of sense or uncommon sense. But often dressed up in empirical language that makes it harder than. I think, where we were, was people in business have got businesses to run. They don’t have time to essentially get a PhD in behavioral science, and they want to know, what’s the principle? How can it be used? How can I use it for my business? If I can’t do it, can you help me do it? So we’ve spent a lot of time working with our clients to share and transfer our knowledge and skills into them. And because we believe behavioral science can be practiced by everybody, if they’re given the right processes, tools and governance to do it properly. And so I don’t know April, if you’ve got anything else to add.

April Vellacott: Yeah. It’s really nice for you to say that Roger, that first of all that it’s really easy to read and also that it’s kind of really accessible and it’s going to help people do it themselves, because that’s exactly what we set out to do. And I think for anyone who hasn’t got their hands on a copy of the book, yeah, hopefully they’ll see when they flick through it, that we’ve also written it with behavioral science in mind to make it really easy to digest and to understand. We’ve tried to keep the language as free from jargon as possible, using really simple, clear English to try and improve people’s processing fluency and reduce that cognitive load that you might get by reading a really dense book about behavioral science. We’ve chunked it into manageable chapters to make it really easy to digest. And we’ve pulled out and made salient the most important bit in the books in, key quotes are pulled out. And so, yeah, we’ve really tried to bake behavioral science into the book itself so that we kind of practice what we preach and make it as easy as possible for people to start doing it themselves, as you say.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, that’s very meta April and it’s cool. And I agree, because you can see those little things in there that you’ve done and you’re trying to minimize cognitive friction in one sense. And it gives me the transition into the effort heuristic, because in Friction, my book Friction, I talk about effort and how it tends to discourage behaviors, which is bad if you want people to buy your stuff and you’re adding effort to the process or it’s good if you add efforts, say to consuming unhealthy foods. But sometimes people expect effort to be an important part of the process. So what I want you to explain that?

Jez Groom: Yeah. I mean, I think we have a kind of a two box matrix, two by two matrix. So I think Dilip Soman in Rotman kind of put forward essentially kind of nudges that are kind of helpful and nudges that are harmful, and then nudges that essentially are hard and nudges that make easy to do. So quite often, we’re very, very careful about our design is to say, are we designing this to essentially make it easy for the customer and helpful and reduce that friction, as you say, such that they’re not taking away sort of cognitive capacity to do things which shouldn’t be hard to do. So I think, you document the world, it’s like application forms, user journeys, emails, in conversations, all that type of stuff.

But we also talk about positive friction. So there are some times where you don’t want an extremely fluent process. You do want people to engage with system two, at which case you’ve got to stop them and essentially build in some positive friction, that we like to call it. And often in financial services. So when you want people to really think about, is this the right insurance product, of course you need to display the different ranges of insurance products in the right way so they understand them. But you might have a number of different stages that they need to go through to see if it’s the right one for them, which takes some more cognitive effort. And I think that the flip side, which again you know and some of the listeners might know is that people actually feel those positive friction experiences even more satisfying. So it’s kind of like, I suppose one of those conundrums with behavioral science, you’ve got essentially effort is bad in some cases, but effort is good in some cases. And it’s about that sort of nuance and understanding when and where to reduce friction and when to add in the positive friction.

Roger Dooley: Well, yeah, and you had a story in the book too, about some people, I think they were cleaning clothes, who expected to exert a certain amount of effort. And if there was too little effort, it didn’t seem like they were getting it done. It reminded me of an old story that maybe apocryphal, I’ve heard that this actually might not be true, but it’s a sort of common wisdom that when cake mixes were first introduced, they included everything. Now, all you need to do is add water and pop it in the oven and you were done and that they weren’t selling well. But when they required the housewife, who was the principal consumer at the time, to add an egg, then that seemed more like baking and they started selling. So, people sometimes need to feel that if they’re doing the process right, they’re putting some kind of effort into it.

Jez Groom: Yeah. I mean, similar on the cooking. I worked on a famous brand of mayonnaise. And one of the guys who was kind of thinking about behavioral science came in with a really crazy idea, like a really crazy idea. It’s like, “Why don’t we create a video which teaches people how to make mayonnaise?” And the client’s sitting there going, “Why would we do that?” Because they wont buy out product. And what he knew because he tried to make mayonnaise and I’m not a great cook. April is far better than I. But making good mayonnaise is really quite hard. So their thought process was if we demonstrate that actually it takes a lot of effort and a lot of skill to create good mayonnaise, then people might try it, get a bad result and then come out the other side to go, “You know what? It was fun and interesting, but I’m just going to buy this brand of mayonnaise and save the bucket from now on because it’s a hell of a lot easier.”

So yeah, I think, the counterintuitive nature of the human brain is kind of strange sometimes. We talk in the book about risky and brave ideas and often it takes a certain type of client, a certain type of business that has got that type of bravery and courage to try these things out. And sometimes they don’t work, but sometimes they do. I mean, in this case they make the film and the customer reaction was exactly that, that people actually liked the mayonnaise more because they respected the way that it was made.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Or if like me, I would probably watch about the first 30 seconds of the video and say, “I can buy a jar of that stuff for $2. I’m done.”

Jez Groom: Yeah, exactly. Might not even get there. Yeah.

Roger Dooley: And so one thing that I’ve written about occasionally is the power of food samples. And oddly enough, April, you had a story about food samples in the book. Why don’t you tell your story?

April Vellacott: Yeah. It’s a story that we included in the book because I wanted to bring to life how people often use things from behavioral science quite intuitively. Like Jez said for his example, people understand that first impressions matter. But they might not necessarily have that kind of academic term to attach to that thing that they know. So when I first moved to London after graduating, I got a job at a food market. It’s one of the most famous markets in London, it’s called Borough Market. And it’s been there for like over a thousand years, I think there’s been a market on that site. And I was working on this bakery store and the days were long and they were very cold as well. So I used to squirrel away a lot of the snacks out of boredom. But something else we’d do out of boredom was cut up the really, really rich, dense brownies and give out samples to customers.

And it was amazing the effect that it had, just by trying this tiny sample of our brownies, people would, they’d buy something from the store and more often than not, it wouldn’t actually be a brownie. And the thing that looking back I realize I was using, was this principle of reciprocity. So I give you something and then you feel like you want to return the favor with a benefit in kind, because you hate feeling like you owe me something. So people would try this little sample brownie and they would buy something else from the store. So yeah, they’re the principles that even market traders have been using for thousands and thousands of years. And even if they haven’t put a name to it, they’ve kind of been using it unwittingly.

Roger Dooley: Right. And I guess it’s pretty clear that what you have there is reciprocity, not just the fact that, “Oh, Hey, this Brown is really good. I’m going to buy some of those.” Because in fact, they were buying bread and other products that weren’t necessarily brownies. So yeah, it’s very, very nice little demonstration. I’ve written about it. We have in Texas, in Texas only, of the 50 United States, supermarket chain called HEB. And there they’re quite dominant in the State and they are also the number one ranked supermarket in the country for customer preference, really outranking, even folks like Trader Joe’s and Costco who have a very loyal customer following. And one of the things that they do is extensive sampling throughout the store. And I think it has multiple effects. It invokes that reciprocity effect. It does occasionally sample of product and you say, “Hey, that actually is pretty good. I’ve bought the exact product they’re sampling because I said, wow, I want to have some of that when I get home.”

And also it creates a sense of fun and excitement through the store too. So really, it works in multiple layers and their biggest local competitors simply doesn’t do that. And I don’t know that I’ve ever been in that store where they’ve had somebody handing out samples and it just feels flat. And it’s not quite the end of that story, but eventually HEB opened up a second store, very close to their competitor. And now their competitor’s parking lot is mostly empty because people weren’t going there as much to begin with. But with the nearby HEB store, now it’s almost deserted. So they do a lot of things right and one of those is sampling. So I was surprised to find that nudges even work with criminals. One of your more interesting examples, how did you find that nudges affected the behavior in positive way of criminals or I don’t know if they’re ex-criminals? Or once you’re a criminal, are you always a criminal?

Jez Groom: Yeah. That was a really interesting brief. And this is what I meant earlier on about working in advertising was fun and actually behavioral science could apply to lots of problems, which advertising agencies would never even get asked. And we’d done some work, a member of the award panel, like the jury, had seen this work, he was in financial services. But he also had a number of different kinds of programs. And one of them was like a rehabilitation program. The people that are on probation or parole. So they’ve been in jail, tends to be relatively low level crime and then they come out, and they’re on various programs. It might be like an alcohol rehabilitation program, drugs, sometimes community service. And then they have to check in with their probation officer, they’re called the case manager.

And what was, I suppose the challenge was that if you missed an appointment, then it caused problems, so it put up a signal. And most of the time people didn’t want to miss their appointment, but life gets in the way. Sometimes they have quite chaotic lifestyles. So they have to ring in to their probation officer. And the way that it worked was the probation officer is seeing like 30 different people across the week. So you couldn’t get ahold of them on their mobile, but you could ring into a contact center. And if you rang the contact center, they could see all the diary of your probation officer. But because the people in the contact center felt like administrative sort of back office staff, quite a lot of the criminals will ring up and say, “Can I speak to my probation officer?” And they’d say, “I’m really sorry, she’s not available at the moment.”

And the say, “Okay, fine,” and just put the phone down. And then they get frustrated and maybe wouldn’t ring back and then miss an appointment. And too many of these missed appointments means that they’ve got a very high probability of going back to jail. And it can be solved quite simply. So we did two things. So the first thing was, we just changed the way that the people on the phones introduced themselves. So rather than saying, “Hello, can I help you?”, they kind of introduced their title and their actually probation consultants, that was their title, and say, “Hello, my name is Jez and I’m a probation consultant here. Can I start by taking your sort of account number or your customer number?” And they give the customer number. They get all the details in front of them that go through some security check and they’d say, “And how can help you?” And say, “Well, I need to change the appointment.” And they say, “Well, I can do that for you right now on the call. I can see there’s availability next Thursday at three. Ill put you in there.” And they say, “That’s absolutely fantastic, great.”

So a simple thing of adding authority at the beginning of the call, the introduction of the call meant that the people on parole were just far more likely to, I suppose, trust, be compliant and go along with the flow of what the authority said and we measured it. So we had pre and post. So we didn’t have a split group on this experiment, we had a pre and post. And we also changed some things on the letters that they got. So they got these reminder letters, which were just really badly designed. So there were written like letters that maybe could written in a typewriter in 1892, and weren’t really salient for the time of the appointment or the numbers that you had to call to change it.

So people would often not even read these letters. So the combination of letters that were hard to read and ring you through to a back office meant that it was just a system that had some inheritance or negative bias within it. So we made these changes, we refreshed the letters, we changed the conversations and we saw over 100% increase, it’s was like 103% increase, in the first contact fixed rate. So whereas before they were getting maybe half people saying, “Yeah, that’s fine. Sign me up.” They got another half again of people saying, “Yeah, this is a great thing to do,” which obviously saves a lot of time, efficiency and a better customer experience all around. And I mean, I think it’s fair to say that nudge theory isn’t a silver bullet and it’s not magic. So for sure not everybody is going to be influenced by these kinds of small changes.

And especially when you’re dealing with hardcore criminals, because there were some people that were on parole that have been in and out of jail for 30 or 40 years. And they’re a bit more resistant to that sort of interaction. But that said, it was a great result. And yeah, it was really, really interesting. And for further work that we’ve done, clients in the business world often say to us, “Well, we’ve got a very, very challenging environment.” We often have people ringing up about complaints and saying that our products aren’t great. And we’re like, “Yeah, it’s okay, we’ve worked with criminals in the center of the England.” So I think we’re okay. I think we’re okay.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. That’s great. I think you mentioned a key point there, and that is salience in any kind of written communication, whether it’s a letter, paper letter or an email, people do not read and it’s something I get reminded of constantly. These days, a lot of people are spending time on social media and you will see somebody post something and they will start getting replies. And it’s clear that many of these replies never got past the first sentence or two, or they miss the key point in their fifth sentence that would have made whatever their comment was, meaningless. But just people don’t read stuff. And I’m sure you’ve sent out emails to people and realize that, “Oh, hey, well, nobody read that,” or didn’t read it through because of their reply and just using some of these visual cues to eliminate anything that isn’t necessary, but also then to make prominent those things that are important and to use language that’s easily processed as opposed to more difficult to process. All those things can make such a big difference in communication.

April Vellacott: Yeah. I wonder whether that point, Roger, I wonder whether you could argue that that’s becoming even more important than ever. With everyone, like you say, consuming really snackable content on social media. If our attention spans are getting shorter, like people might hypothesize that they are, I wonder whether they’re going to think things like saliency are going to be even more important in the future.

Roger Dooley: I think so until we can get our information overload under control. I just saw a study from Adobe and this is a self-report study, so I guess I would take the numbers with a grain of salt, but people who responded were spending on average more than three hours a day on work email, and more than two hours a day on personal email. It sounds a little high to me unless some of it’s by task, like I’m doing business emails while I’m in a business meeting or something. But regardless, this is people’s perception that they’re spending five or more hours a day in email. And so you can imagine that they’re trying to get through that as rapidly as possible. They’re trying to get the essence of whatever communication is and figure out if they have to reply, if they can delete it, if they just file it and they aren’t going to be reading every word.

Jez Groom: No, no. It is interesting on that point. I mean, myself and April have just been working with a financial services client. I think financial services and utilities are definitely the worst sectors for information overload. They come with a lot of compliance, which I think actually creates a negative effect. But myself and April, only last week, we were looking at an email and the objective of the email was to get a customer to confirm their details. So they’d signed up to a financial product and we just needed to them to confirm their details before we could activate this particular product. And we looked at this very, very simple email and there were 14 friction points on this simple email. And it’s staggering that, like the subject header is wrong or isn’t motivating enough for you get to open it. The purpose of the email, isn’t very clear from the start.

And essentially it feels like their financial services company is doing you a favor by you buying a product, it’s free and the wrong way. They then come up with like a five step process, which sounds really complicated in like an Excel spreadsheet format. And it’s really unclear what you’ve got to do. And then it gets signed off by a guy who’s selling you the product and you’re sort of like, “Yeah, I’m not so sure it’s a sales person.” And then the reply address was new business at this company. And you sort of like, “Yeah, I’m not so sure these things are right.” And that our key frustration, I think at Cowry, is that there’s quite a lot of behavioral scientists that are very, very good at the science, but frankly, bloody awful at the design.

So designing what the email intervention should look like to change the behavior, such that the customer gets what they want to do in as easy way as possible. So we have a team of five designers at Cowry. They’re all psychologists, but got real strong passion for graphic design. And they bring to life these academic principles. So myself and April are pretty good at the words and the conversations, but these guys and girls bring, so it should sit on the left, or should it sit in the right, what color should it be? And how big should it be? What order should these things be? Is there an icon? All these, what font is it? Is it bold? All these sorts of things really, really do matter. And then design something for intervention to change behavior. I mean, there’s so many letters and emails get written as if they were written on a typewriter from an 1819.

And you kind of like, “Hey, I’ve got this crazy idea. Why don’t we put a picture in this one, which shows the person doing the thing that they want them to do, which is maybe, I don’t know, on a website type in register and they look quite happy about it.” And that’s going to essentially people go, “Oh, right, that’s what this email is about. It’s about registering and feeling happy about signing up. I think I might do that.” And it seems so obvious to us, but I think quite a lot of people certainly think in the business world just haven’t been exposed to a lot of these behavioral science principles. And that’s all we wanted Ripple to do, to say this is a principle that once you’ve been taught and told it, then you experiment with it and if it works then great, then you can do it throughout your life, your career, across all these different channels.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Sometimes it’s just common sense. I think Jez, people have occasionally come to me saying, “Okay, we need to implement some kind of a nudge strategy here to increase our sales.” And you look at their website or the email, whatever it is and it’s just so badly designed you don’t need a nudge strategy, you need people to be able to find the buy button. It’s not rocket science. But anyway, we could go on forever here, I think. But let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Jez Groom and April Vellacott, behavior change experts and authors of the new book, Ripple: The Big Effects of Small Behaviour Changes in Business. Jez and April, where can people find you and your ideas?

April Vellacott: So we actually created a website to go along with the book Ripple because there were so many case studies and stories, like we’ve touched on today, that had videos and stuff to go with them. So we’ve got this companion hub online, which you can find at www.ripple-book.com, and it’s full of videos, articles, extra content so you can delve deeper into the stories behind each of the chapters and start doing it yourself. And from there, you can also can connect with us and you can buy a copy of the book, which is available now. I think it’s available in the U.S. on Amazon. And I think there’s an audio book coming soon as well. I think that’s going to drop any day.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, by the time this airs, I’m sure all of those things will be available. And we will link to that website to the book at Amazon and any other resources we spoke about on the show notes pages at RogerDooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Jez and April, thanks for being on the show. It’s been fun.

Jez Groom: Thanks so much, Roger. It’s been a lot of fun.

April Vellacott: It’s been a pleasure. Thanks for having us.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.