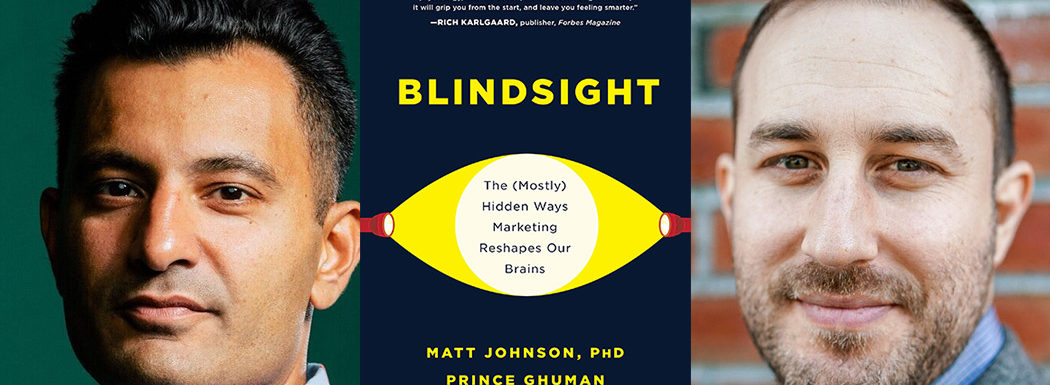

Prince Ghuman is is a Professor of Neuromarketing at Hult International Business School, holding dual roles as the U.S. Director of Consumer Marketing and the Global Director of B2B Marketing for OFX. Matt Johnson is a professor, researcher, and writer specializing in the application of neuroscience and psychology to the business world. Together, Matt and Prince have co-authored Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes Our Brains, a book about the surprising relationships between our brains and brands.

Today Prince and Matt join the show to discuss the impact that certain marketing may be having on your brain—without you being conscious of it. Listen in to learn why it is so important to make your advertising transparent and ethical in order to build trust with your customers and how to create a memorable experience to build loyal customers and a long-lasting brand.

Learn how to build trust between your brand and your consumers with @PrinceGhuman248 and @mattjohnsonisme, authors of BLINDSIGHT. Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The impact marketing has on your brain that you may be unaware of.

- Why the amount of distrust in brands has gone up in recent years.

- The importance of making your advertising ethical and transparent.

- How to give your customers a memorable experience.

Key Resources for Prince Ghuman and Matt Johnson:

- Pop Neuro: Blog | Twitter | Instagram

- Prince Ghuman : Twitter

- Matt Johnson: Twitter

- Amazon: Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes Our Brains

- Kindle: Blindsight

- Audible: Blindsight

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. Today we have two guests on the show, Matt Johnson and Prince Ghuman. They are the authors of the new book, Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes Our Brains. Welcome to the show, Matt and Prince.Matt Johnson: Thank you. So good to be on.

Roger Dooley: To start with. I’m going to let you explain who you are and what you do, to paraphrase my friend and podcaster extraordinaire, Miss Joel. So Matt, you go first.

Matt Johnson: Fantastic. Yeah. So my name is Dr. Matt Johnson. I’m a professor, researcher and coauthor of the book, Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes Our Brains. My background is primarily in academic neuroscience. That’s what I did my PhD in and Prince provides the marketing half of the neuro-marketing combination that we are.

Roger Dooley: Great. In your case, Doctor is an earned title, as opposed to your co-author Prince where he’s not actually royalty. You can explain that Prince.

Prince Ghuman: I’m Prince Ghuman. I am a chief marketing officer turned professor and now turned author of Blindsight and so much so that Matt is my research Batman to the Robin. And then I’m the application-heavy person to be the Batman to his Robyn. There. So, happy to be on the call.

Roger Dooley: Great. Glad you guys could join me and do it together too, which is really great. So I’ve written about Blindsight once or twice, and it’s a really weird phenomenon. People who are not just legally, but truly blind can somehow manage to navigate around obstacles in a hallway. Explain their kind of blind sight and what’s going on there.

Matt Johnson: Yeah, absolutely. So it’s a very rare neuro-psychological condition where the person themselves feels as if they’re blind. So when there’s internal subjective experience, it’s complete darkness, but what’s really interesting is with this very specific community, they still exhibit some behavioral evidence of still having visual information. They can still react.

So you sit someone down who has blindsight, you toss a ball at them, they can actually reach out and grab it and you ask them, “Well, you’re blind, how did you do that?” And they don’t have a great explanation. It’s intuitive, you felt it was coming, you could actually do similar experiments where you sit down in front of a computer and you flash different lights and you asked, “Well, how many lights flashed?” And they’re like, “Why are you asking me that, I’m blind. It’s so insulting.” You just prod them to guess and if they make a guess, it’s actually staggeringly accurate.

So they do actually receive visual information. But what’s really interesting is that it just doesn’t breach the level of our conscious awareness. So vision is such a fascinating process. We feel as if it is a monolithic process, you open your eyes and there is the outside visual world. There’s many different complicated pathways sending visual information back to the brain. The visual pathway, which gives rise to conscious visual experiences is damaged and the ones which still can influence our behavior, thoughts and emotions is actually preserved in this very rare condition. So it leads to this very interesting behavioral profile.

Roger Dooley: Well, does that tell something about normally-sighted people, do people who don’t have some major visual impairment also have this non-conscious visual processing going on?

Matt Johnson: Absolutely. That’s really what the fascinating thing is about the condition is, we all have these pathways. We all have conscious visual pathways. We all have non-conscious visual pathways and when we open our eyes and we’re experiencing the world, we never notice that these are different pathways and they’re bifurcated in different parts of the brain. It’s really only in the case where we have these very specific types of brain damage that we do see how complex and how multifaceted vision is.

So these unconscious pathways are really geared more to our fundamental reactions. So really geared towards acting on visual information, not to analyzing information. So you think about a pencil and your conscious visual pathway, there’s very specialized regions for processing color and the width and the shading and you get all the richness of the pencil, but imagine a scenario where a pencil is thrown at your head. Now, it doesn’t matter what color this pencil is, doesn’t matter the exact hue that you’re able to perceive with your complex visual system, you just got to get out of the way. And that’s what these unconscious pathways are for. They’re just for detecting very hoarse amounts of visual information and getting us to react based just on that.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. So before we give people the wrong impression, the book is not all about this strange visual phenomenon. It’s also used in a metaphorical sense, right?

Prince Ghuman: Yeah, it is. We use Blindsight because it was such a great analogy for how the consumer world works. So, in the same way that you’re able to dodge obstacles, rather being able to see anything because your brain is picking up many other signals in the periphery. We wanted to use that to tell the story of marketing. There’s a lot more to marketing than just a billboard you see. It’s what the impact the billboard had on top of the store maybe you walked into that was on the billboard, to the online experience. And you’re only conscious of such a small part of it. So really we named the book Blindsight because it breaks down and it really is a great little frame to have for the amount of impact the other aspect of marketing that you’re not conscious of is having on your behavior every day.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. So one description of the book I read implied that it may, it’s probably from the publisher, that it was a consumer-ish book, designed to protect people’s brains against being manipulated by marketers. But in reading the book, I found it to be more neutral in nature. It wasn’t implying that all marketing is evil and manipulative nor explicitly how to manipulate consumers guide to marketers. So was that your intention to try and steer a path between the two extremes?

Prince Ghuman: Absolutely. I mean, Matt and I are really passionate about this and this is one of the driving force behind why we wrote this book and I’ll speak personally. I’ve spent a lot of time being a marketer, but I’ve spent a lifetime being a consumer. And especially in the last 10, 15 years, the amount of distrust in consumers and products and brands has gone up. And there’s something about that that didn’t make me feel too good as a marketer. And vice versa. So marketers want to create great products, but for whatever reason, there’s this separation between them. And we wrote the book to be the bridge between consumers and marketing.

We wrote the book because look, we want to show how the sausage is made. It doesn’t make it any less delicious knowing how it’s made, if anything, knowing how it’s made will make you appreciate the amount of time and effort it takes into making it. So we wanted to do this book right by making it for the consumers, but clearly, and we’ve got marketers in the room here. Clearly, so much of marketing is not taking into account the psychological impact of marketing. Some very select and well-funded teams and brands certainly do that, but we know that there’s a big difference between Coca-Cola’s marketing department and a small, medium, or even a large size company that’s not Coca-Cola.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). And I think there are certainly techniques that businesses of any size can use here, hopefully in an ethical fashion. That’s something that I always try and emphasize in my writing. Yes, this is a technique, but just about any technique can be used in a manipulative fashion if you want to. Heck, the simplest ad can be manipulative or even deceptive if it contains false information, but that doesn’t mean all advertising is bad. It just has to be done in an ethical and transparent way.

The first part of the book, you describe a lot of the cognitive biases and quirks that marketers exploit. And I think probably our listeners are familiar with a lot of these, but one is the peak end effect. And that says that people tend to remember the peak points and the end of an experience much more than the entire experience, particularly if it was a lengthier experience. So I’m thinking to explain the research that sort of led to that conclusion and in particular, the colonoscopy research, which I found to be really fascinating.

Matt Johnson: Absolutely. So the peak end effect is just a really fascinating window into this disconnect really between experience and memory. So we feel as if, when we’re having an experience that we just have the record button on, and then we feel as if, when we’re recalling this memory, we’re just pressing the rewind button, but neither of these things are actually true. And when you look at experience itself, there’re certain aspects of the experience that reliably weighted much more heavily in memory. And so this is what was originally pioneered in the famous Kahneman colonoscopy studies or infamous, depending on your views on it. Essentially what they did here is they allowed for people who were taking part in the colonoscopy, the patients at the colonoscopy, it’s painful enough as it is but now you’re asked to essentially tell on a dial exactly how much pain you’re experiencing at any one moment.

And then after they got this data, they would ask the people after the procedure and two weeks later, how painful do you remember the entire experience to be? And so now they have these two data points, they have the actual moment-to-moment pain that they received in the procedure, and you have their memory for how painful it was. And what they found interestingly is, it wasn’t the overall aggregate amount of pain which was correlated with a painful memory. It was two very specific things.

One was the peak. So if, and this is a little bit of a graphic detail, so apologies to listeners, but if the doctor’s hand slipped or something happens where there’s just this amazing shot of pain just in that millisecond of time, even if it’s just for a very, very small amount of time, if there’s an immense intense peak in that experience, the whole entire procedure is remembered as being very painful. And the other thing which stood out is the end. And so if the end was painful, the entire experience was remembered in a painful manner. If it wasn’t so painful, then the whole experience wasn’t actually remembered very painful at all. And this led to a followup experiment where they actually elongated the procedure and they had appeared at the end of the procedure where the colonoscopy device was actually left in, and this wasn’t comfortable, but it wasn’t as painful as the actual procedure.

And so you elongate the amount of time, elongate the procedure, more aggregate pain, but because the actual pain at the end, wasn’t very intense, the overall memory for the painful experience was not as high. So a really interesting example of just this disconnect between experience and memory. And the really great thing with the peak end effect is that it pertains not just to negative experiences like colonoscopies, but also to very positive experiences as well. So you’re going to remember much more of the peak of the experience at the end, whether it’s a positive experience or a negative one.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I want to get to the customer experience implications of that but before we have dissuaded all of our listeners from ever getting a colonoscopy in their life, even if their doctor wants them to do it, I have had them and in recent years, I think their techniques have improved considerably with anesthesiology that they are not at all painful. But this is really a fascinating experiment because prolonging this bad experience actually improve people’s memory of it. And I think there’s a lesson there for anybody who is designing customer experience. On one thing I’ll throw out and then maybe you guys have some input on that, back when we could travel, I was a moderately frequent cruiser. I’d go on cruise ships and these are typically many days, might be a week or two weeks, or certainly there are much longer ones, but they’re not ones that I usually go on.

But you know, in the two week experience, you’re going to visit a bunch of places. You’re going to have some great dining experiences and you really don’t remember all of that. As you say, you haven’t recorded a mental video of the entire experience and so you remember the unique things, maybe there was a hike across a dormant volcano that melted your sneakers. I mean, you’re going to remember that for years and years, it’s a pretty distinct memory or an incredible dining experience someplace on a cliff-side restaurant. But the other part is the… And see those points are going stand out or something really bad too. If you got stuck standing on a hot dock for three hours because now the ship couldn’t pick you up or something.

But the end of cruises always ends up being very anticlimactic. If not unpleasant, you’ve got to pack your bags the night before, eat your breakfast in the morning, it’s kind of a rush. Then you sit around waiting for your turn to be called to get off the ship. And there’s a mad dash for luggage and then you go through immigration and customs. I’m curious, if either of you folks has any idea of how that experience might be modified a little bit so that it ends up being at least a little bit better way to finish that off for the travelers?

Prince Ghuman: I agree. And I love the science of memory because it really does go back to what we’d started the conversation off with. It’s not so much exploited. I think this is a great way for consumers, because consumers want memorable experiences, whether it’s a retail store or a cruise or at a music concert, we want to make memories. And as people, as marketers, as designers of these experiences, you want to be remembered as a product as a brand. So, it goes back to that bridging the divide. And I think one of the things that I would suggest is adding an element of a positive surprise at the end, because they’ll remember that. So, is there a way at the goodbye step off, is there something that the cruise line can do beyond just letting you go, waving back at you?

You see a lot of restaurants that use this really well, and you see a lot of restaurants actually tap into the element of surprise towards the end. Typically, it’s Michelin-starred restaurants, but nonetheless, there’s that element there. And to answer your question, Roger, I think we have to sit down and truly think about how we can create a better end for cruises, but really walking through what it’s like to be part of that experience. And I’ll be honest, I haven’t been on a cruise, but there’s better ways to create that experience.

Just think about when you leave a best buy or a Costco and you have such a good experience with Costco sometimes, but at the end you’re like, “Okay, I want to make sure that you’re not a thief.” Best buy, I want to make sure you’re not a thief. And that’s the end of my experience with best buy, as opposed to Apple. You walk into an Apple store and you leave and that friction isn’t there and that’s the last thing you remember. They always say hello to you as you walked in to always say goodbye to you as you leave. And it doesn’t seem fake. So, and that’s a perfect example of a good end versus a bad end. And we’re looking at best buy who’s clearly thought about their customer experience. They’re missing that piece.

Roger Dooley: That last minute, once over when the person at Costco or Sam’s Club looks in your car to see if you’re not… they make sure you’re not walking off with anything you’re not supposed to. That also signifies a lack of trust, which when they signify that lack of trust in you, that will lead you to trust them less. And one of my favorite examples is Amazon, where you return something to them. And by the time you get back to your home or office, after dropping it off at ups, it’s been scanned in and you may have your account credited already. They don’t know that you returned the exact item you were supposed to, but they trust you and that in turn causes you to trust them. And so, yeah, I suppose there’s a good business reason for having that last checks and step because there’s a lot of stuff on the shelves that people could walk off with, but it’s not the best end.

Speaking of ends in retail. One example that you use in that same area is at the Amazon Go store. And at first I was kind of perplexed by that because I was thinking, “Okay, well, wait a minute, there is no end experiencing a Go store.” You get your stuff and you walk out, but the mere lack of a checkout process, of a waiting line, having to get your credit card out and everything else, much less have somebody inspect to make sure you’re not shoplifting, that itself at least in your initial few visits is going to be kind of a wow experience like, “Whoa, Hey, that was really cool.”

Prince Ghuman: It is. And just so the listeners are caught up to it, the example we use is the anti example to show the point of the peak end effect, which is, you always remember the peak or the end are these experimental Amazon Go stores. As far as I understand, there’s only one in your Amazon’s headquarters, Pacific Northwest, one in San Francisco and I think there’s one in New York City, but there’s not a single checker. You walk straight in, you pick a product and Amazon knows you picked up the product and you walk straight out. It is so frictionless, but in the context of all the other shopping experiences, the peak at this moment of experiencing the store really is the fact that you’re walking in. There’s no one there. And in the end, you just walked out and they charged your prime credit card if you have it and on the way out.

And that totally feels like the next, of course, it’s hard to pull that off with $4,000 laptops, but nonetheless. I’m not quite sure Apple’s retail boss is going to design this sort of experience around that for obvious reasons but for Amazon, it totally works. There’s no reason why other others can’t try it, but I love the trust angle. You’re right. Roger. It’s like, they’ve been able to create that trust subtext that they do with refunds with their Amazon Go stores.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I talk the Go stores and also Alibaba was in my stores in my Friction book. And you two mentioned friction briefly in your book and in the context among other things of difficult to read fonts, which I also cover now, from my perspective, I advise marketers to always use the simplest easiest to read fonts because there’s plenty of research showing that when people read things in more difficult fonts, they perceive that the effort involved in whatever it is that they’re reading about is greater. They’re less likely to follow instructions, even important medical instructions and such, but in your book, you make the good point that there is a positive aspect to it in that there’s some research showing that when a font is difficult to read, people will remember what they read more. So where do you think the balance is there? What should people be doing in that font battle between easier, harder and so on?

Matt Johnson: Yeah, it’s a really good question. I mean, I think it’s just a really interesting thing we’ve converged both of us on in terms of friction, is that friction can influence different aspects of the consumer experience and consumer decision-making in different ways. So as you rightly point out, there is a large swath of literature, really attesting to easy to read fonts, really being what’s more enjoyable, much easier to bring to bind. A lot of this is done by Adam Alter and Danny Oppenheimer. It’s really well done research and very robust findings there. On the other side though, when you look at fluency from the standpoint of memory, we actually see a slightly different effect here. So if you’re able to make the font slightly difficult, you force the reader to strain their attention slightly to bring the information to mind. Evidence suggests that actually boosts the memory for whatever you’re reading.

And this is the Sans Forgetica font, which we talk about in our book and you talk about it in your book as well. So, it speaks to the flexibility which marketers really have to have when they are organizing their consumer experience and designing for specific outcomes. So there’s really no plug and play when it comes to these elements of friction. So if you’re designing for something, you really just want it to be enjoyable for that moment and irrespective of whether it’s remembered, or if that information is digested, then a much more fluent, easy to read font is best, but if you really want the information to be processed and you want that information to be encoded, then introducing a little bit of friction can actually boost the later memory for that.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think I’d be inclined to use that harder to read Sans Forgetica font on something like a billboard, something very short text, because if you give somebody even a paragraph of difficult to read text, they just aren’t going to read it. In a lab setting, you can say, read this paragraph, people will read the paragraph because that’s what they’re being told to do but in a consumer setting, you just can’t rely on people to do anything. One thing that I’ve noticed lately, everybody’s on social media even a greater extent than usual and the amount of non reading that goes on is incredible. A poster will ask a question about something and they’ll get replies that show that the person responding got to about the first four words of it, or the first sentence, completely ignored everything else and as a result gave a not totally inappropriate, useless reply, people just do not like to read. They will make as little effort as they can.

Matt Johnson: Absolutely. I mean, it really speaks to the law of these mental effort when we’re engaging in this very exogenistic-driven attention when it’s things in our environment which we’re just responding to, the amount of effort that we’re giving to process these things is very minimal. So we see that a lot in terms of how this affects online behavior and really how it affects consumer decision-making as well.

Prince Ghuman: And just to piggyback on what Matt said earlier, if you want to remember a book because you’re studying it for school, or you just want to absorb more of it than reading in Sans Forgetica at least in theory will help you remember it better. But Matt also said, if you want to optimize for the experience itself, then that piece of friction might not help. I feel like we can talk about it in terms of fonts, but I think it’s really fun to talk about it in terms of events.

In which case, you’re not thinking about optimizing a retail store experience as much, or you’re not thinking about optimizing a website where you don’t want to add enough friction, but if you want someone to remember your billboard, instead of making it a billboard, finding a way to interact with it, which is a form of friction actually helps not only memory, but if you do it right, it’ll actually create an experience. That’s in terms of finding the balance. So instead of getting… We mentioned this in the book as well as is, if you’re selling pianos and you have a billboard for a piano, why not buy out the set of stairs at a subway so that when people are stepping on your piano keys, there’s that little bit of interaction there. And it can turn up one more level by adding lights every time you step on it. And you can turn up a second level by making it makes sounds, as people are stepping on it.

Every single time, technically, that’s friction. It’s more friction to step onto a walking billboard that makes sounds versus just looking at it, but it adds, I would argue, joy or experience and an age to the memory.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. It’s not diminishing the person’s experience in any way when that happens. It’s not like they have to go through a maze to get up the steps when they’re just trying to get home or something. A few years ago, I was involved in higher ed marketing and one of the hot techniques that the company I was working with was using was sending a personalized video to applicants and these are really pretty cool and fun. The applicant would get a video personalized to them. They would see these school mascot holding up a welcome sign with their name on it. They might see a dorm room with their name on it, swinging open, and this would actually be pretty well done.

So it looked fairly realistic as opposed to something that’s just a mirror, like a subtitle on it or something of that nature, or maybe they’re in the stadium at a football game and the jumbotron says something about them. So pretty cool experience. But in your book, you’re talking about the future of marketing and you talk about face swap videos, explain that concept and how far we are from actually being able to realize that.

Prince Ghuman: I love this conversation. So the future of marketing, one of the things we bring up in the book is the future of face swap videos. But really what we talk about is digital fakes. Just earlier this month, so in the book we mentioned a digital model. It is a model who is not a real person who was a supermodel. She has deals with some of the higher-end luxury brands like Fendi, Tom Ford and she recently signed a record deal and will be in an entertainer album probably dropping soon. So the point Matt and I love to make is this.

If they can make a supermodel and a DJ in a virtual form, that people are buying and paying large sums of money for, they can definitely make a fake of us, of the three of us, of everyone listening. And that’s where we talk about face swap. An example of face swap is that app that came out about a year and a half ago, which people took photos and aged themselves 40 years, made them younger and ultimately the product creator walked away with digital rights to fake photos of you. So, and this is where we go back to the two square one, this weird level of mistrust between marketers and consumers and understand the implication of that, I think goes down the discussion about privacy and data and creating digital products and what that means in the future. Matt has something to say, I can see him raising his hand. Go ahead, Matt.

Matt Johnson: Yeah, just to piggyback on that. I think the face conversation is especially interesting and it’s compounded by the fact that we have a special place in our attention for our own faces. So this is the visual cocktail party effect. So the auditory cocktail party effect is a very old, very robust effect in psychology, where if you’re at a cocktail party and you’re engrossed in the conversation you are currently having, you’re looking directly at somebody, if you hear all of a sudden out of the corner of the room, Matt or Roger, whatever your name is, your ears will peak up. And so you weren’t listening a millisecond ago and you weren’t paying attention to these people in the corner of the room having a conversation, you have this residual amount of attention bandwidth which is designated just for these very highly salient stimuli, such as your own name.

And a piece of research which came out about a year ago, found the same thing but with our own faces. That our attention is drawn to things even if we don’t consciously recognize it as our own face, as we paid more attention to stimuli, which actually has our own face in it. And so with this finding, this could be a very, very potent type of marketing technique where you’re scrolling through your Facebook feed, Facebook, Instagram have tons of aggregate photos of you. You could easily see a banner ad for Nike shoes or a grill, whatever the case may be, but it’s your face. It’s you advertising to yourself. And that could a very potent form of marketing, which might not be too far in the future.

Roger Dooley: And LinkedIn has been doing that for probably eight or 10 years. I’ve used that as an example of both good and bad advertising, where LinkedIn will put your photo, which they just pull from your profile which is pretty straightforward, in an ad for… like a recruiting ad for somebody or an ad, you might like to follow this brand. And it’s good in that it gets your attention because as you point out, Matt, when you see your face over there in the margin, it’s like, “Hey, what’s my face doing in the margin?” And you’ve got to look at it, but then it says, “You might like to follow a Comcast business.” Yes. Well, why would I want to do that? You’ve given me no reason other than putting my face in their ad.

So, if you’re going to personalize it, you need an effective message to as to why that’s relevant to you, but it does work. And I can imagine once they manage to do videos that way… As you were talking, I was visualizing a video for a vacation resort where your fake supermodel is welcoming a fake you to the resort and showing you around as if you’re actually part of this immersive experience and that would certainly hold people’s attention for a while, I think.

Prince Ghuman: Imagine if it wasn’t LinkedIn. Imagine if it was a life insurance commercial, a car insurance commercial, but with your face on it. And it doesn’t have to look exactly like you. So the attention grabbing nature of the cocktail party effect is amazing. You can see a Ray-Ban ad in your Facebook or Instagram feed, and it just has to look enough like you, that it pauses you from the habit of ignoring the surfing the feed and boom, you got the attention and minus the creepiness of them actually being you, it looks close enough to you, you might not even think anything about it. And now you got your attention. Sorry, Matt, I cut you off. What were you’re going to say?

Matt Johnson: Yeah. No, just to jump on top of that. Yes. I mean, the photo thing is relatively easy. I mean, they’ve been doing that for about a decade, but really what the advent of the face swap technology, they’ve had full movies now, which you can watch and you are Leonardo DiCaprio in Titanic. You are frame for frame him at every moment of that movie and the same could conceivably exist for these ads, which I think could be much more potent than the video feature. Yeah. Or the photo feature rather.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative) And I think to the unexpected nature of it, like now, I think we’re pretty much inoculated on LinkedIn to those ads because they’ve been there for so long but if you were watching a television show and your face popped up in a commercial, that would definitely get your attention right before you shut down all your electronics and fabric.

Prince Ghuman: Put tin cans on your head and be done with it for the day. Yeah.

Roger Dooley: One point you make in the book is that persuasion techniques are not binary in terms of effectiveness. In other words, there’s a spectrum ranging from not effective at all to guaranteed effective. And I think that probably most marketers recognize that when we do conversion optimization testing, whether it’s AB testing or some other kind. We can see, “Okay, well. Hey, this has no effect. This has a 5% conversion and so on.” But I’m curious as to whether anybody is using this scale in the way that you presented in the book that is there a technique that is 90% effective or something like that, where, I mean, that’d be pretty cool to have where you could show people that, but I’m sure it’s more of an individual thing, isn’t it?

Matt Johnson: Absolutely. Yeah. So this is what we had discussed in the book in terms of the ethics of marketing. So as you described really any given marketing campaign, the effectiveness of it on an individual level really exists on this spectrum. If they do nothing, it’s 0% effective. You’re equally likely to engage with this product or not, all the way up to hypothetically a hundred percent, which is that if you are exposed this marketing campaign, you are virtually guaranteed to make this purchase or call to action or whatever the marketing campaign is geared to do. And really marketers aren’t going to get any worse at persuasion. So as they have more information on you, as they have more information on your purchasing behavior, what you’re likely to do, more information about the brain and how it processes information, marketers aren’t going to get any worse at moving up this scale.

And so really the ethical question we wanted to raise here is really a hypothetical one which is, at what stage along this spectrum, is it to persuasive? Is it if a marketing campaign is on average 10% persuasive? Is that too persuasive? Clearly I think most people would agree that if it’s 80, 90, a hundred percent, when we pull our classes just anecdotally people get uncomfortable with anything about 75%, but really where should the line be drawn? And then the other question we ask in tandem with this is what other factors should matter.

So if you have a very, very, very persuasive marketing campaign, but you’re persuading somebody to ultimately act in their own best interests. So you’re trying to quit smoking and you’re persuading somebody with a very potent marketing campaign to quit smoking. Is that more okay than if you are trying to persuade them to continue smoking, which is not in their longterm interest. And the bit of research we’ve done on this is that people tend to be very, very utilitarian in their judgments. They really don’t care too much about the sheer persuasiveness of the advertisement. Even if this does involve some subliminal messaging provided that the outcome of the campaign is actually in their best interest. So the research is still early, but I think the spectrum of persuasion is a really interesting way to look at that.

Prince Ghuman: Yeah. The consumers take on marketing ethics being so consequentialist is very interesting. I think, all the marketers listening out there that it still shows, despite all the talk about lack of trust, consumers are putting trust in us as long as we don’t abuse it to create a product that is ultimately better for them. That’s what early research is showing. However, that’s putting a lot of trust and sometimes marketers don’t know what is better for them. It’s one thing to create whatever ‘quit smoking’ app or ‘make me healthier’ app from running or whatever that may be, that supposedly adds a better habit to you and nudges you towards that behavior. But that’s giving quite a bit of trust into marketing.

So Matt and I, when we wrote the ethics chapter, our goal was to provide a framework to push this conversation on. It’s not to say this is right, this is wrong. It’s to create this continuum for ethicists, for public policymakers, for marketers and active consumers to have this conversation openly. Because stuff like face swap stealing the digital rights of two-year old infant photo of you does not scale long term. It can’t. For ethical reasons but also, there’s only so long that consumers who don’t know about it will find out about it and they’ll be absolutely livid at said product.

But there’s a way to find that middle ground. I think one of the ways is what I call the definition of marketing, which is trading value. Ultimately, how am I as a consumer getting value from your brand and your product and how are you attracting value from me as a marketing team, as a brand. And in the book, we talked about that. When that relationship is transparent, people are happy. When that relationship is unfair, then you have an unfair trade of value and that’s where you have stuff like face swap, or someone might say Facebook, where it’s not entirely clear how they’re extracting value from you. And that goes down that rabbit hole of discussion, but between the continuum and the new definition of trading value, I think that’s a good place to start to talk about marketing ethics.

Roger Dooley: Right. And that’s probably a good place to wrap up too. I think we can encourage all our listeners to use these techniques in an ethical and transparent fashion, because if you don’t, it will come back to bite you sooner or later. So, let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Matt Johnson and Prince Ghuman, authors of the new book, Blindsight: The (Mostly) Hidden Ways Marketing Reshapes Our Brains. Where can people find you two?

Prince Ghuman: They can find us on popneuro.com. And the book is on Amazon. It’s on all major booksellers everywhere, online and offline.

Matt Johnson: In addition to the website, popneuro.com also I can follow me on mattjohnsonisme on both Twitter and LinkedIn.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Prince and Matt, thanks for being on the show.

Prince Ghuman: Hey, thank you for having us, Roger. Appreciate it.

Matt Johnson: Thank you so much, Roger. It’s been a pleasure.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.