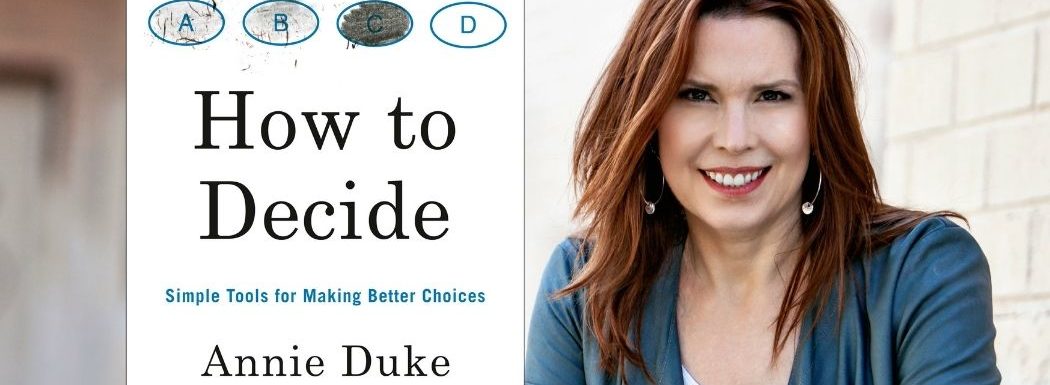

Annie Duke is an author, speaker, and consultant in the decision-making space. She was awarded a National Science Foundation Fellowship to study Cognitive Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and—when she was close to completing her Ph.D.—put that on hold to become a poker professional. Annie won more than $4 million dollars in tournaments before retiring from poker almost ten years ago. Now the co-founder of The Alliance for Decision Education, Annie joins the show for a second time to share insights from her new book, How to Decide: Simple Tools for Making Better Choices.

Listen in as she explains why the decision-making process does not have to be fraught with anxiety and self-doubt, but rather that it’s a skill we can all learn. You’ll discover why we often get stuck in decision-making, as well as how we can overcome the second-guessing and analysis paralysis that often plagues the process so we can make better choices with more ease and confidence.

Make smarter, better decisions - cognitive scientist and poker champ @AnnieDuke, author of HOW TO DECIDE, shows you how. #decisionmaking #cognitivebiases Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Watch:

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- A synopsis of the science behind decision-making.

- How bias plays into the decision-making process.

- Why it’s important to bring other people into your decision-making.

- Why we need to be aware of feedback loops.

- The origin of the “freeroll” model and how you can apply it to your decision-making process.

Key Resources for Annie Duke:

- Connect with Annie Duke: Website | Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn

- The Alliance for Decision Education

- Amazon: How to Decide

- Kindle: How To Decide

- Audible: How To Decide

- Amazon: Thinking in Bets

- Kindle: Thinking in Bets

- Audible: Thinking in Bets

- Angela Duckworth

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. Most of us aren’t very intentional about making decisions. What we have to decide, we decide. Sometimes we procrastinate, but ignoring decision making is a mistake. Jeff Bezos recently announced he was stepping down as Amazon’s CEO, thinks a lot about decisions. Meetings start with everyone reading a short document that ensures everyone knows the objective and has the same information before they decide. Meetings where he’ll have to make an important decision are scheduled for 10:00 AM and never in the afternoon. And he was recently quoted as saying that if he makes three good decisions a day, that’s enough. And they should be just as high quality as he can make them. How many business leaders do you know that work that hard to optimize their decisions?

The good news is that today’s guest can help you make better decisions. Annie Duke author, speaker and consultant in the decision making space. She was awarded the National Science Foundation Fellowship to study cognitive psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and when she was close to completing her PhD, put that on hold to become a professional poker player. Annie became a champion and won more than $4 million in tournaments before retiring from poker almost 10 years ago. She’s the co founder of the Alliance for Decision Education, a nonprofit that empowers students through decision skills eduction.

The last time Annie joined us was to discuss her bestselling book Thinking in Bets. Her new book is How to Decide: Simple Tools for Making Better Choices.

Well, Annie, welcome to the show.

Annie Duke: Well, thank you for having me back.

Roger Dooley: Annie, decision making is clearly something that’s important for all of us, but how many people think they need a better decision making process? I’m kind of reminded of say weight loss. People buy weight loss books because they know they’re overweight. They know they need to do something, but I would guess that an awful lot of people think, “Oh, my decision making process is pretty good. I mean, I know how to make them. Sometimes I make some decisions quickly. Some I agonize over. But hey, what’s to improve?” Is that really true, do you think?

Annie Duke: I think not only is that true but it’s kind of reflected in two places. One is the educational system. We don’t really teach decision making, like K-12. If you do get a decision making class, maybe it’s in college. So that’s reflective of the fact that I think people don’t really think they’re overweight in this case in terms of decision making. But the other is even the history of science. I think that people don’t realize because now we’re all kind of so immersed in Thinking Fast and Slow and that genre, which puts kind of Thinking in Bets in that genre. I mean, obviously I’m not the caliber of Daniel Kahneman. So I had to make my contribution.

But when we think about the history of the science of decision making, up until the ’70s when Kahneman, Tversky, and Richard Thaler were doing their work and really sort of trying to scream, at that time, sort of into a void that people aren’t so rational and they aren’t so great at making decisions. That up until that point, everybody assumed the rational decision maker, that everybody’s making decisions in their own best interest. And that given good information, people are rational. When you looked at the work that was being done, it always assumed rationality. So even science up until the ’70s was assuming that people were pretty good at this.

Now when Kahneman, Tversky, and Richard Thaler come along and a variety of other great cast of characters comes along. They start saying, “No. Actually when you look at it, decision making is plagued by a cognitive bias and by noise.” We start to understand slowly but surely that we’re not that good at it, and then obviously in 2014 Thinking Fast and Slow comes out. And then the general public starts to get wise to this, and you start to see this explosion in this literature, people letting you know. So I think it’s not surprising that individuals don’t realize that they’re not good at it because it sure took science a long time to figure it out.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, from the studies I’ve seen, Annie, people will acknowledge that other people are affected by cognitive biases. They can totally understand how some other person would have a problem with that, but they know that they themselves don’t have that problem, which I don’t know if there’s a name for that cognitive bias, but it’s certainly something that’s pretty common I think.

Annie Duke: Yeah. So there’s an act or observer bias, and there’s also the fundamental attribution era, which is another one, which goes into that. But there are biases that show that we view other people differently than we do ourselves. And then there’s also some more subtle ones. There’s something called naïve realism, which is kind of interesting. Which is you assume that the way that you view the world is correct, and if other people don’t view the world the same way you do, you assume they’re either wrong or evil.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Annie Duke: Because they must-

Roger Dooley: I can identify with that, Annie.

Annie Duke: Yes. Because they obviously must have it wrong because you’ve got it right. So these all fit into the same category, but we can sort of put this into a broad bucket, which is the inside and outside view. So Kahneman talks about this a lot that the inside view is like the world through our own perspective, from our own experiences, kind of viewing the world from the inside out through our own eyes. You can see how the cognitive bias would be living there. If we’re thinking about confirmation bias, we’re trying to confirm our own beliefs. Not trying to confirm anybody else’s. So we have the way that we model the world and sort of how we think things work and what a good decision looks like and so on and so forth. That’s going to be all on the inside view, and that’s where a lot of the era lives.

The outside view would be the world from the outside in. In other words, looking on yourself as if you were standing outside yourself or the way that you view somebody else in a situation. So the outside view has two pieces. One is just what’s true of the world independent of any human being. So the Earth is round. It doesn’t matter if I think it’s a trapezoid. It’s just round. Base rates would go into this. I could think that if I open a restaurant next year, it’ll be 90% to succeed at the end of the first year. But if I go and look at what’s true of the world in general, I would find out that that’s actually a 40% chance of succeeding in the next year. So if I saw that there was that kind of variation between what the world is in general versus what I think, I should want to resolve that and maybe adjust my… Not necessarily all the way to 40% because what is true of me matters, but I want to sort of get somewhere in that gravitational field.

So that’s one thing, but the other thing, as you point out, is the way that somebody else would view the situation that you’re in. Because other people have different information than you do. Sometimes you could have the exact same information. We see this in politics a lot. You’re looking at the exact same information, and you come to completely different conclusions about it. Sometimes you actually look at the same information and you model it identically. But you think you should do different things about it.

So this is why when we look at other people, we see them much more rationally than we see ourselves. Not that we see other people as rational. It’s that we see them more objectively than we see ourselves because those cognitive biases that are carried in the inside view that have to do with protecting our own identity and our own beliefs and the way that we do things and what we think is right. We don’t carry over into when we look at other people.

So when we look at other people, we’re like… They’re doing something, and you’re like, “You’re so dumb. Why are you doing that? It’s so obvious,” or, “That’s totally confirmation bias. Look at you, you’re clearly just reasoning to get to the conclusion that you want.” And we can see it so clearly in other people in a way that we can’t see it in ourselves, which is why it’s actually so incredibly important to bring other people into your decision process so that you have people who can spot those errors in yourself, just like you can spot them in other people.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Now one of the major decision making flaws that you described pretty early in the book, Annie, is resulting, and that is analyzing a decision that you made based on the results. And then changing how you might act in the future. So if you decided something based on probability and it didn’t work out twice in a row, you might at that point say, “Okay. I know that the numbers say I should do this, but it’s not working out. I’m going to do it the other way.” I guess you would disagree with that strategy, right?

Annie Duke: Yeah. Here’s the problem that we all have as decision makers. The way that we learn is from experience. Okay, I do something; I get a result. And then I figure something out from it. So you can think about simple, the kid touches a stove when it’s hot, and they’re like, “Oh, hot,” and they don’t do that again. And that’s really good that we connect those two things together. “Oh, I burned myself. I shouldn’t do that anymore.”

Now when it comes to physical things like, “I touched a stove. Ah, that was bad. Probably bad decision to touch the stove. I shouldn’t do that again.” When we get into more abstract things, we actually it’s an error to do that. And the reason is that when we think about that sort of what is the correlation between touching a hot stove and it being an unpleasant experience? It’s correlated at one. It’s not luck involved in that. We should want the individual to just not touch those things because it’s sort of better safe than sorry.

Actually, so it’s not correlated at one. Let me just rephrase that. So when we’re thinking about hot stoves, the thing about it is yeah, that stove could be off. The burner could be off. So sometimes it’s off; sometimes it’s on. But from the standpoint of sort of protecting yourself from harm, you should just not want to touch the burner. You should not want to really put your hand on the burner, particularly when you’re a child and you may not know the difference between when it’s on and when it’s off.

So from a survival standpoint, that actually makes a lot of sense. You’re going to have a lot of what we would call false negatives where you don’t touch it and actually it would’ve been fine. But we would prefer you not to touch it at all. So we have this preference for false positives. I just don’t touch stoves.

Now basically when we think about decision making, when we get into more abstract things, we end up with these problems in terms of the way that we learn from experience, which is we sort of act like that one time it works out poorly, that tells me what I need to know about the decision quality or that one time it works out well, it tells me what I need to know about the decision quality. In a way where we act like it’s correlated in the same way that sort of touching a hot stove would be.

So if it works out poorly, if the ball is intersected in a football game or if you lose an election or if you lose a sale or if you hire an employee who doesn’t work out, we can imagine a lot of examples of this. What’s the first thing we think? What a mistake. That was stupid. We shouldn’t have done that. Likewise if you hire someone who does work out or you win the game or you win the election or whatever, we say, “Obviously that must’ve been great decision making that led to that result.”

Now here’s the problem with that. Let’s take the hiring example. Think how incredibly uncertain you are when you hire somebody. You’ve got a CV. You’ve done some series of interviews. You’ve called some references. They maybe better references than others. Like maybe you took the time to get some references that weren’t on the person’s list. It’s a good thing to do. But that’s about it. What else do you have? Think about how little information that is for somebody who you’re trying to form a long term relationship with as an employee. A lot of uncertainty.

So you can kind of come up with a best process you can, and it’s going to work out some of the time. It’s not going to work out some of the time. Kind of no matter how good you are because you just don’t have a lot of information. But then what ends up happening is that if it works out well, we say, “We’re a genius,” and you’ll go and you’ll try to hire people like that again, or you’ll ask the exact same interview questions that you ask before because you think they’re like super high signal in some way. That job description, you’ll just repeat it because that got such a great candidate into the job, and you just assumed that that was really good.

If it works out poorly, you go and you want to change everything. But in neither case, not on one time is it particularly good signal that the person worked out or didn’t. It actually doesn’t say that you’re hiring process was great. In fact, your hiring process could be pretty crappy, and you just got really lucky and ended up with a great person in the role. Or the hiring process could be amazing, and you got unlucky. And this person who interviewed so well who had such a great CV and referenced really well just for whatever really turned out to be a disaster in the job.

So when we’re closing these feedback loops, resulting becomes a really big problem because we just really learn the wrong lessons when we’re closing the feedback loop in that way.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So beware of feedback loops. One concept that really I found pretty intriguing, Annie, was the free roll concept. What is the origin of that name, and what does it mean when it comes to decision science?

Annie Duke: Oh, gosh. Yeah. So it’s always good to have a lot of mental models that you can apply to situations, and free roll is one of my favorite models. So free roll comes from… The origin is kind of fun. So I don’t think this is apocryphal, but I’ll just say there’s some small probability this is apocryphal. But let’s assume for the sake of this conversation that it’s not and it’s true.

In the 1950s when you would go visit a casino in Las Vegas, they would give you a roll of quarters when you walked in the door. So it was a free roll of quarters that you could then go use to play the slots. So here’s the idea. So this is where we get to free roll. The idea was I’m giving you this free roll of quarters, and then you can go play the slots. Sorry, it was nickels. I apologize. It was the 1950s. It was nickels.

Roger Dooley: Annie, had you been there then, they probably would’ve given you quarters or maybe even dollars.

Annie Duke: Maybe.

Roger Dooley: For the average better, maybe nickels.

Annie Duke: Yeah. But it’s a free roll of nickels because it’s the ’50s. They weren’t giving out quarters like candy back then. I think a quarter bought you a lot back then. But anyway, they gave you a free roll of nickels to go play the nickel slots. So now we can sort of get a sense of a what a free roll is. So what they were saying was I gave you this for free. If you lose it, you’re really no worse off than when you walked in the door. So it’s kind of all upside. Now obviously this was a marketing ploy. I mean, first of all, it would’ve been better to put that in your pocket. And second of all, the whole point was once you started playing the slots, you are obviously going to dig into your own pocket. So that’s obviously why they were doing that.

But we can take this concept of a free roll. You’re no worse off than you were when you walked in the door. We can take that to decision making. So a free roll is when you’re facing a decision where it is possible that the decision is quite high impact. An example of that might be if you’re thinking about offering on a house, obviously the house you buy is going to be a pretty high impact decision. You’re trying to decide whether to offer a really aggressive settlement in a lawsuit. If that works out, it’s going to be pretty high impact. That would be another example of this kind of situation that comes up.

So what happen when we’re thinking about the upside, if I get my dream house that’s kind of out of my price range, this is obviously going to make a really big difference in my life. If I offer this settlement that’s kind of like really at the upper end, maybe even out of range of what I think is reasonable and it works out, that would be amazing. So we’ll sort of cycle and really worry about whether we should actually do it.

I think passively, I think mostly because we’re afraid of they’re going to say no or they’re going to reject it. But we want to use the free roll example, which is if they reject it, are you worse off than you were before you made the offer on your dream house? And the answer is absolutely not. All you did was get a no. You’re not actually worse off than you were before.

So if we can do that frame as we’re approaching decisions and say, “If the worst of the reasonable outcomes occurs, am I really worse off than I was before?” Then this tells us this is something that we should probably engage in because what that means is that we’ve got very little risk. So like the downside is just limited. So you just don’t have a lot of exposure to the downside, but the upside is quite high.

So there’s actually right now, this second, a really good example of a free roll. I wrote a paper on this with Cass Sunstein where we used this as an example. And it’s whether you should wear a mask or not during the pandemic. So what I’ve seen from people who are kind of against masks is a lot of discussion about do they actually prevent the disease. That’s the main one. Do they actually prevent the disease? I sort of dismiss the question of freedom because you can’t tell me to do it in a store because they’re wearing pants. So I’m just going to dismiss that part, and I’m going to focus on the thing that they actually are quite concerned about, which is there’s a lot of arguments about what their ethicacy is. Do they actually work?

So I’m going to take those as good faith arguments that there’s questions about the ethicacy of the mask. But what we want to do is look at it from the framework of a free roll. What’s the downside to wearing it? And the downside is I’m not sure. If you didn’t brush your teeth, I guess maybe you have to smell that a little bit more. In the summer, it might make you a little hotter. Although in the winter, it makes you warmer, which is kind of nice. But there’s really kind of, if you think about it, there’s not a lot of downside to wearing a mask. And the reason that we know that there’s not a lot of downside is that masks have been used for other reasons besides trying to prevent coronavirus for a very, very long time. Your surgeon wears a mask when they do surgery on you. So we know it doesn’t cause death. It doesn’t case hypoxia. You don’t faint. We know that none of that is true because we have a lot of data on that because doctors have been wearing masks for a long time without ill effects from them.

So now we’re using it for this novel thing. Let’s prevent coronavirus. So we already know, we have a lot of knowledge about the downside. So the fact that we don’t have clarity or a lot of information about the upside is like completely irrelevant in this case because we know that you can only win to the decision, and that’s the thing about the free roll is that it’s like you can only win to it even if you’re unsure about how much you might win. But you can’t lose. This becomes a very important way to think about a lot of different problems.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I like the example that you give in the book of deciding between two desirable vacation spots, Rome and Paris, where clearly you could spend any number of hours researching both destinations, comparing their plus, assuming you’ve been to neither one and they were roughly the same price to go to. But boy, they each have such unique characteristics and cultures and restaurants. You could really go crazy trying to decide where you make the point that that is in essence a free roll, right?

Annie Duke: Yeah. So I call those hidden free rolls where for the reason that the question that you’re asking with the free roll is what’s the worst that can happen? Can I really be that wrong? So in the case of a mask, when you say, “Can I really be that wrong?” The answer is not really because nothing really bad happens even if I am. So this is a little bit of a different category. It’s not a free roll in the technical sense of a free roll, but it’s got some very free roll like qualities to it. Which is that whichever one you choose, can it really be that bad a choice? So that’s where we get into that kind of free roll flavor of this particular decision.

But it gets to this really deep issue of a lot of times when we’re facing decisions that we feel are really hard, it’s actually a signal that they’re actually quite easy. So you describe that what’s the difference between Paris and Rome, and you gave a very good description. Not much. So they’ve got great food. They have great architecture, lots of history. They’re beautiful cities. They’re walkable. They have very similar climates. Great shopping. So as we’re thinking about what are the things that would meet our criteria for a vacation that we would want to go on, I’m assuming you’ve thought about what can I afford? Do I want to go to a walkable city with lots of history and great museums and amazing food? I assume that’s why you got down to Paris and Rome because you were thinking about what those criteria are, and now you sort of thought about the criteria you have, you’ve narrowed it down to Paris and Rome, and you spend months or you’re agonizing over it.

But the whole point is that they’re the same, at least from the standpoint that you live in. So I say this phrase all the time. You’re not omniscient and you don’t have a time machine. And if everybody could just keep that in mind when they’re making decisions, they would relieve a lot of anxiety. So you’re not omniscient. You don’t know everything there is to know about Paris and Rome, assuming you haven’t been to them, and even if you have, you don’t know what it’s going to be like this time. And you don’t have a time machine. So you can’t view yourself on the vacation to try to figure out which one would actually give you more joy.

So absent that, given the things that you have preferences about and what your constraints are in terms of your resources for where you’d like to go, they’ve met those criteria. And now you’re looking at two things that are identical, and that’s why we get held up because we have the illusion that we could distinguish between the two if we just went and tried to get more information. But the information doesn’t exist. The information you would need is the time machine, and you don’t have it. So once you realize that, what you can do is step back and do something that I call the only option test. And this is what allows you to get out of that analysis, that never ending analysis loop.

So here is the only option test. If Paris were the only choice that I had for this vacation that I would like to take, would I be super happy? Yes, I would love to go to Paris. If Rome were my only choice for my fabulous vacation that I want to take, would I be super happy? Yes, Rome is an amazing place. Okay. So now what you’ve discovered is that they’re both amazing options. At which point you should actually just flip a coin between the two because from your standpoint, you’re sort of choosing between identical things, and that tells you sort of to the point of that free roll quality that whichever one you choose, you can’t actually be that wrong because they’re kind of the same. It’s like choosing between two oranges. Who cares. Just pick one.

That then gets us to again, another level deep, which is to say what we should care about is sort of thinking about decisions through the framework of the sorting process versus the picking process. So the sorting process is that stuff I talked about, which is like well, what are your constraints? How much money do you want to spend? Do you want to be in a walkable place with history, fabulous architecture and food? Or maybe the criteria that you’re trying to meet are like, “I want to relax on a beach, get a sun tan, go swimming and wake boarding,” so on and so forth. Well, obviously Paris is a bad choice for that.

So once you’ve decided, “Here are the things that I desire. This is what my goal is for this vacation. These are what my constraints. This is what I can afford,” and you’ve got options that meet those constraints, that’s the sorting process. Do I want to go to Paris or the Bahamas? Because those are going to be different choices. But once I’ve sort of settled that and I’ve sorted it into options that would be pretty great, I can really flip a coin because that’s just picking. And picking should take no time at all because that’s when you’re getting into that free roll-ish area. They’re the same. Just flip.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Probably now alienated our French and Italian listeners who would point out that there is no way those cities are the same.

Annie Duke: That is true. They have more information than we do, and also, wait, that’s the inside view.

Roger Dooley: Very good, very good.

Annie Duke: So from their perspective, they’re like, “No, my city is much better than the other city.” But the Parisians are saying, “No, my city is much better than Rome,” because they’re both from the inside view.

Roger Dooley: Right. The counterintuitive part is that you say that making those decisions sound be the easiest where if it’s a decision between say Paris and Cleveland, chances are you’re going to pick Paris.

Annie Duke: Well, no knock on Cleveland though to be fair.

Roger Dooley: No, I spent a year in Cleveland and met my wife in Cleveland. So it’s not a bad city. Given the choice, I would probably go to Paris, as would many people. So that seems like an easy decision. Where choosing between Paris and Rome seems very hard, but actually you say, “Well, because if they both meet your criteria, then you shouldn’t spend any time deciding at all.”

One interesting thing that it kind of relates to this decision making process, I was just listening to a conversation between Steven Levitt and Paul Romer, and they were talking about important life decisions. And Romer had made some kind of zigs and zags in his professional career. Leaving academia and doing some other stuff. And Levitt described some research that he had done that was published I think just last year on decisions where people were agonizing over a major decision whether to break up a relationship, whether to start a new job, or move to another city. And basically they had them decide randomly and then check back on them year later. And they found something interesting that related to change, and they found that even though the decisions had seemed very difficult. In other words, both options tended to be quite similar. In other words, leaving and breaking up, they both had advantage and disadvantages.

The people who made a change after this random say coin toss decision ended up being happier two months later and six months later than the ones who had stayed in their situation. I kind of attributed that to… I don’t think you call it a status quo bias, but I think that’s sort of the essence of it. That change is difficult. People tend to avoid change, not like change, and therefore that will figure into their waiting process. So these two decisions seem equally weighted, but actually if you somehow look at them dispassionately, maybe that new activity, that new relationship, new city, new job, whatever would in fact be better. But it’s not benefiting from that.

I thought that was kind of an interesting little twist on that.

Annie Duke: Yeah. So I love that you brought that up because that particular work makes a pretty significant appearance in my next book. So we’re on the mind meld here. So I love that work from Levitt because basically what that shows us is there’s an old term in carnival games that you can talk about something being gaff. So what do we mean by that?

So those Wheel of Fortune or whatever that you see at a carnival, some of those midway games and things like that back in the day. I mean, this obviously illegal. But back in the day, they would be fixed. So if you had a big bet that something returned high odds, that wheel would be gaffed, and we’ve seen this in old movies and things like that where it would be spinning and someone presses a lever or steps on a pedal or something like that and it stops. And obviously you lose.

So I guess a simple thing would be like if a butcher put it’s thumb on the scale, that would be gaffing the scale.

So I think about this concept of the gaff scale as it relates to the Levitt work, which is what happens when we’re trying to decide between the thing we’re already doing, a job we’re already in versus quitting and going and doing something else. It turns out that it’s gaffed towards sticking with the thing that you’re already doing. And there’s all sorts of reasons why it’s gaffed. You mentioned one of them, status quo bias would be one of them. Sunk cost is another. But that goes broadly into this problem of escalation of commitment that we tend to over persevere in courses of action that we’ve already sort of invested some time and resources in.

So people talk a lot about grit. It’s an incredibly important concept. Obviously Angela Duckworth’s work is amazing, and she’s talking about the under perseverance side of it. Like we quit things too early. But there’s a whole body of work. Barry Stas is one of the big people in this world that’s really about over perseverance, and there’s a lot of forces that cause us to continue in losing endeavors.

So given that there’s a lot of forces that cause us to continue losing endeavors, the way that I interpret that work from Levitt is that what he discovered is that the scale is gaffed. So that when you get to a point where you think, “Should I stay in my job or quit?” And you’re actually having a serious conversation with yourself about it. It means that quitting is really the huge winner because the thumb is on the scale for staying. So given that the thumb is on the scale for staying, if you’re saying, “I think it’s an equal option for me to leave,” that means that leaving must be the way better choice.

So he had this site, as you said, where people would go and it would like flip a coin for you when you had those tough decisions. And not everybody listened to what the coin said, but of the people who listened to what the coin said and went and switched, as you said, you check in on them six months later. Turns out they’re a lot happier. And I think it’s for that reason. I think it’s because the scale is gaffed. Sticking with the thing you’re doing, there’s so many cognitive forces that are pushing you to do that that when you get to a point when you think it’s close, it’s actually not close at all.

Roger Dooley: Well, that is probably a great takeaway to end up on here, Annie. If you have a difficult decision that involves change and they seem about right, you should probably opt for the change. That’s what the science says.

Annie Duke: That is what the science says.

Roger Dooley: That’s great. Oh, one thing, I was going to ask you about your Alliance for Decision Education. Can you explain just a little bit about that?

Annie Duke: Thank you so much. I appreciate you bringing that up. So yeah, so we kind of started the conversation saying, “Geez, it seems like people don’t really know they’re bad at decisions.” That is reflected in our educational system. So the science sort of started to figure this out back in the ’70s, and then they were sort of laughed at. It took a really long time, and finally now Thaler and Kahneman both have Nobel prizes. But it’s been a while coming. And that’s obviously kind of like the science recognizing it, and now it’s maybe business is recognizing that this is something that’s really important. But our educational system is certainly lagging behind.

I think that most parents don’t recognize that they have a problem with decision making. I think they probably think they’re pretty good and that it’s their job to teach their kids great decision making. So it just doesn’t appear in our curriculum. So you look at K-12 education, there’s just an absence of it. There’s a lot of trigonometry, which is pretty useless. I mean, if you’re going to become a mechanical engineer or structural engineer, I’d like you to know trigonometry. But you can take that in college. And we should be teaching things that are more germane I think to decision making, like statistics and probability and how do you actually frame decisions and habit formation. I mean, there’s all this whole world of decision skills that we think about for, certainly in the popular literature, in the science. Businesses are thinking about them. Let’s get them to kids.

So that’s really what the mission of the Alliance of Decision Education is is we believe that better decisions lead to better lives, which lead to a better society. So we ought to be getting decision education into the K-12 curricula. This is something you should be getting every year, and we have a model for this, which is social emotional learning.

So up until about 10 years ago, nobody had heard of social emotional learning. It wasn’t in the classroom. Now for anybody who has children who are in this age range, they’re all getting some kind of social emotional learning in school. My kids it was called SEED, and there was a SEED class every single year that they were in school and that you had to take it. It was a requirement. So it’s sort of appeared out of the blue. But it wasn’t out of the blue.

What happened was there were organizations, one of them is called CASEL, that had been working for over two decades to start to try to build that field and get people to understand that this is something really, really important when we’re thinking about these whole child and 21st century skills. And how do you navigate the much more complicated information in societal environments and also just technology and job paths. What is someone’s career going to look like? You’re probably not going to be the same thing you’re whole life anymore like we used to think. That we need it to equip them with these good SE skills, which social emotional learning. So we also need them to have good RQ skills, which is the decision making side, and we think that you need to serve the whole child.

So we’re using the model of CASEL, which really worked behind the scenes in order to build this field and create push and pull in order to get social emotional learning in the school day. And we want to do the same for decision education.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, I would encourage our audience members if this program is not reached or if any program is not reached their particular school if they have kids, spend a little bit of time teaching them how to make better decisions. And I think your book, Annie, How to Decide is a great place to start. It is so full of really kind of simple hacks that will make you think about your own decision making process in a different way. So Annie, how can people find you and your ideas?

Annie Duke: So you can go to AnnieDuke.com. That’s my website. Also, I would love people to go to the Alliance of Decision Education. You can get there through AnnieDuke.com or you can go directly and search the Alliance for Decision Education. But if you go to AnnieDuke.com, you’ll find lots of videos of me speaking. You’ll see an archive of newsletters. You’ll see a contact form, actually, which is really important to me. So not just for hiring me, which would be great if you wanted to, but more because I love to hear from people who have heard me on podcasts or interacted with my work or read my work.

So much so that I would say that it’s just true that How to Decide would not exist if I hadn’t been interacting with a lot of readers who had read Thinking in Bets and were asking me, “I get it. We’re pretty bad at decision making. Uncertainty is a beast. I don’t really know how to navigate it now that I kind of have my eyes open to it. So tell me how I would actually construct a really good decision process.”

So they were looking for something that was more practical and grounded than what was more sort of high level ideas in writing in Thinking in Bets. So I created this actually for my readers because they asked for it. So I love hearing from my readers. It’s where I get a lot of my ideas from. I understand what challenges they are facing, which is incredibly helpful for me.

So please use that contact form on AnnieDuke.com. And then you can also find me on Twitter @AnnieDuke. I’m reasonable active there. It just depends. I’m in the middle of writing a new book right now, so I’m a little less active at the moment. But I try. I try.

Roger Dooley: Great. Okay. We will link to all those places to Annie’s books and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast where we’ll have audio, video, and text versions of this conversation.

Annie, thanks for being on the show. It’s been fun.

Annie Duke: Well, thanks for having me. I appreciate it.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.