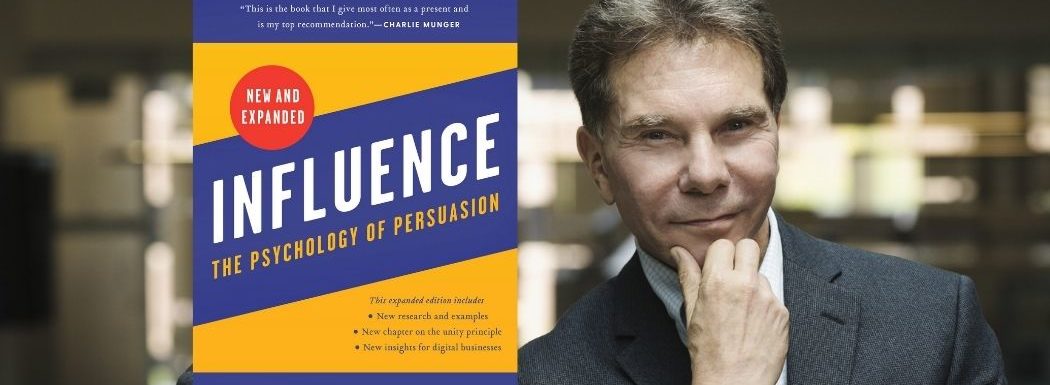

Dr. Robert Cialdini is known as the foundational expert in the science of influence. His Principles of Persuasion have become a cornerstone for any organization serious about effectively increasing their influence. He is a New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and USA Today bestselling author, with over five million copies sold in 44 different languages. He is also the president and CEO of INFLUENCE AT WORK and a popular keynote speaker.

Dr. Robert Cialdini is known as the foundational expert in the science of influence. His Principles of Persuasion have become a cornerstone for any organization serious about effectively increasing their influence. He is a New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and USA Today bestselling author, with over five million copies sold in 44 different languages. He is also the president and CEO of INFLUENCE AT WORK and a popular keynote speaker.

Many listeners are familiar with Bob and his Principles of Persuasion, but the launch of his new and expanded book is worth revisiting his theories on the psychology behind persuasion. Listen in as we discuss how to use shortcuts for persuasion, why words can be a powerful force, and how to use one particular social technology to up your persuasion game.

Learn the foundations of influence and #persuasion with @RobertCialdini, author of INFLUENCE, NEW AND EXPANDED: THE PSYCHOLOGY OF PERSUASION. #robertcialdini #principlesofinfluence Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The basis of Robert’s principles of persuasion.

- Why shortcuts are sacred to persuasion.

- How to supercharge your persuasion with the law of reciprocation.

- How the power of words can help with persuasion.

- How coordinated actions can lead to feelings of unity and persuasion.

Key Resources for Robert Cialdini:

- Connect with Robert Cialdini: Website | YouTube | Facebook | LinkedIn | Twitter

- Amazon: Influence, New and Expanded: The Psychology of Persuasion

- Kindle: Influence, New and Expanded

- Audible: Influence, New and Expanded

- Coffee with Scott Adams

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. It would be corny to say that today’s guest needs no introduction, but Dr. Robert Cialdini is likely known to almost every member of our audience. He’s been on the show before, of course, but he’s the author of multi million copy bestseller, Influence. He’s responsible for the way most of us think about persuasion in business in life with his original six principles of influence.

And I’m excited to say that this is an auspicious occasion. Bob is releasing an expanded and revised edition of Influence. Before you say, I’ve already read that, I’ve still got my copy on the bookshelf, let me assure you that this is no minor update. Not only does the new edition incorporate his seventh principle, unity, it has lots of new information sprinkled throughout our E boxes. Examples of how real readers tell us how they either used or encountered elements of the seven principles in real life. And the publisher laboriously catalog 66 new content elements, studies, examples, applications in the new edition.

And for someone like me, who is always trying to learn, the book has another key feature, a bibliography of over 900 citations, plus many pages of end notes with commentary on elements of the main text. Bob, the new edition is epic. Congratulations and welcome to the show.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Well, thank you, Roger. I’m very pleased to be with you again and looking forward to our interaction.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it was so exciting to see this because, at first I wasn’t real excited about another edition of Influence. I mean, it seems like between that and Persuasion, you’ve covered a lot of territory. But having it altogether in one really convenient to consume form with so much information, so much new information, too. If we look at this dates on the studies, these are not all the classic studies in the original book. So it’s really great. I’m just going to kind of skip around here to some of your key principles. I don’t know, if you just want to very quickly enumerate them for the audience, then I have some specific examples I’d like to get into.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Sure. Of course. The first is reciprocation. People want to give back to us what we have first given to them. They say yes to those they owe. So we should put ourselves in a position of giving benefits, giving advantages, giving information, giving a positive mood first. And it will come back to us.

Next is a principal no one would be surprised to know influences the persuasion process. And that is liking. We prefer to say yes to those people we like. But there are a couple of easily implemented concepts, similarity and complements, that allow us to generate a much more positive feeling of rapport with the people around us. If we point out our similarities to them, if we give them genuine praise where it’s deserved, we supercharge the liking process.

Another principle is social proof. People want to follow the lead of many others, many comparable others. People who are similar to them and around them. If those people are moving in a particular direction, that’s a good signal that that’s probably a good direction for us to move, too. So any communicator who can give us that information, that what they have is the most popular or is trending in a particular direction, they will grab our attention and probably our dollars.

Next is authority. People want to follow the lead of true experts. So if we can hook our ideas to the voices of genuine authorities on the topic with testimonials and so on, we will have enhanced the influence process in our direction.

And now there is a commitment and consistency. People want to be consistent with what they have already committed themselves to. Well, what’s a commitment? In academic language, a commitment is what we have already said or done, especially in public. When we’ve done that, if somebody can ask us to take a step that they recognize is congruent with that, what we’ve already said or done, we’re much more likely to leap in that direction and continue to be congruent.

Also, is scarcity. The idea that people want more of those things they can have less of. So if we can show people that what we have is limited or dwindling in availability. Or even if it’s not. If it’s just something that is unique, something that is uncommon, that they can’t get anywhere else, now we have the winds of scarcity in our sales, moving us forward towards success.

And then finally, there’s this new principle that you mentioned, the principle of unity. The idea that people want to say yes to those individuals who are of them. That is, one of them. If you can convince me to say to my fellow group members, oh, not just, “Roger is like us.” But, “Roger is one of us,” all the barriers to influence come down for you at that point. Because we now want to be cooperative with you. We want to be helpful to you. We want to say yes to you. We want to like you. All of those positive characteristics now apply to you.

If we can see you as one of us. So for example, there was a study done on a college campus. A young woman was asking passers-by to donate to the United Way. And she got some contributions. But if she added one sentence before the request that said, “I’m a student here, too.” Contributions more than doubled. Just by becoming, in the eyes of her audience, one of them, now all kinds of positive outcomes accrued.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, I appreciate that summary, Bob. And I got to do something. I need to jump right to the end of the book where you make a point that these mental shortcuts are sacred or should be sacred or used in a very respectful fashion. And because what we talk about is often how audience can sell stuff more effectively, get more sales, and so on. I think this is probably a good point to interject that cautionary note. Explain what you mean by the sacredness of these shortcuts.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: We live in what is unquestionably the most stimulus- saturated, information overloaded environment that has ever existed on our planet. As a consequence, we need shortcuts, decisional shortcuts, that allow us to make good choices without having to process and tabulate, all of the possible pieces of information relevant to each of those choices that we have to make in our decision overloaded day. So these shortcuts, giving back to people we owe, following the lead of multiple comparable others, following the lead of genuinely constituted authorities, and so on, those things normally steer us correctly as to when to say yes.

If they are counterfeited, if they’re fabricated by some communicator who tricks the system by lying with statistics about the number of sales they already have or fabricating a testimonial from somebody who is a purported expert and so on, that’s the trickery we have to oppose at all costs. The person who uses those pieces of information honestly is hardly our adversary. That person is our ally in the process, because they’ve informed us properly. They’ve educated us into a scent rather than tricked or deceived us. Or certainly not coerced us in that direction.

Roger Dooley: And yeah, you give a great example of the sort of ethical and perhaps less ethical use of these kinds of shortcuts with scarcity. Where you recount buying a TV when the sales person told you it was the last one in stock, and then you wondered, “Well, was that really the last one in stock?” And went back the next day and indeed they didn’t have a shelf full of them. So in that case, the salesperson was helping you. If you really wanted that product, you didn’t want to miss out. Then that was a good nudge to buy it now.

On the other hand, there is so much false scarcity we see on the internet. I think that some of it is outright false. I recall one website that, every day, announced that their deals were expiring at midnight and you had to buy now. And then the next thing went back in the exact same deals were they’re in the exact same format. But then there’s this sort of gray area where when you go visit … Actually almost everybody in the travel business now, Bob, does this, where you visited a major airline.

You visit a major travel website. And you see that there’s only two seats left at this price. Or there’s only one hotel room left in this hotel on that day at that price. You say, “Wow, that’s really scarce.” But in some cases, or so I’m told by folks in the know, there are other rooms that are priced very slightly different. So they can truthfully say that there’s only one left at that price. But if you go back later, there’s going to be one priced five cents difference or something very minimal.

Dr. Robert Cialdini : Yeah, right.

Roger Dooley: And so, I think we all have to be on our guard for that sort of thing. And I don’t know if you have any opinions about, where does the gray areas start and sort of the downright unethical begin?

Dr. Robert Cialdini : That’s a good example of one where, it may be true in detail, but it’s not true in spirit. There are many others that are available for a dollar more, right? So it’s a distinction without a difference. And when that is recognized … So for example, when someone blows the whistle on them, that trashes their reputation. Now I don’t want to believe anything they say about their stock of rooms or the number of flights they have with this price available. Now I don’t trust them at all. And that’s really devastating to their future prospects as communicators.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). And you actually encourage our readers of the new edition to call this out when they see it. If they see influence techniques being used in a way that is clearly not the right way, to call it out, either by not purchasing the product or even on social media. So, I think that when we do that … I’ve been encouraging people to call out unnecessary effort when they find a particularly effortful purchasing process that maybe perhaps caused them not to buy or cause them to make a poor decision, to call that out on social. And I think that that’s a tool that we didn’t have fairly recently. Where you simply couldn’t get that kind of traction. But now these deceptive practices can be exposed. And have you picked out a hashtag yet, Bob, for that?

Dr. Robert Cialdini: No, I haven’t done that yet.

Roger Dooley: Well, I’ll throw out one possibility that is bad influence. A hashtag bad influence. So I don’t know if that’s being used for anything else, but we’ll see. Perhaps some listeners or viewers can let us know if they think that’s a good one or suggest something else.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: But anyway, I want to get into some of the really interesting things that I’ve either learned or relearned from the book. And one is, I’ve been really promoting the gospel of frictionless and totally seamless experiences.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Yes.

Roger Dooley: But one thing that you point out very early in the book in the reciprocation area is that sometimes, when seamlessness is interrupted by something bad, that can be an opportunity to create an even greater impact and be even a more successful with the customer. Explain how that works.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Well, of course, people want to give back to those who have given to them. But there is a supercharging dimension within that. If you give something that is personalized to the recipient, they become even more grateful and they feel even more obligated to give back to you at the highest possible levels.

So there was one account that I learned while I was giving a speech at a resort, where the general manager happened to be the audience of my talk. And he raised his hand and he said, “What you just said about reciprocity, it just happened to me today.” He said, “We had a guest who came with her two children to play tennis on our courts. But we have two child size rackets, they were already in use. So what I did was to send my assistant manager down the street to the sporting goods store. And within 20 minutes, we had two more rackets for her children. She came back to me just a few minutes after she completed the match with her children and said … Came to my office and said, ‘I want to book my entire family into this resort over the 4th of July weekend because of what you did for me this morning.'”

Now, notice that what the manager did was to make up for a slip-up. They didn’t have enough child rackets, right? He gave her something to compensate for that error and personalize the gift, thereby, for her. And it was that personalization process that led her then to book the family into the resort in a way that if those two rackets had already been there and he just went underneath the desk and gave them the rackets, she wouldn’t have thought anything of it. It was just “Okay, part of the service here.” But as a personalized gift, something special for her, it required something special for him.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that is so important. And I don’t think that you’re suggesting that companies or brands should create these opportunities by having some shortcoming in the customer experience. But when they happen, they are a golden opportunity to do a great job. And that’s why, I guess, Ritz Carlton empowers their employees to spend up to a couple thousand dollars. Because, in this case, your example, the general manager was able to address this. But had the-

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Exactly.

Roger Dooley: Perhaps well-paid person who manages the sports desk, then the one who experienced that, they would’ve said, “Oh, gee, come back later. I don’t think the other people will be very long.”

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Right.

Roger Dooley: But when you empower people to make these kinds of decisions on their own, they can multiply that experience.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: You’re exactly right that I’m not suggesting you have thin spots in the ice that your customer service prospects or clients can fall through so you can pull them out. No. What I’m suggesting is, where do you put your budget? The idea of making your experience seamless, without any glitches, that’s where you put your budget, you’re doomed to failure because there will always be glitches. We’re talking about human beings. They make mistakes. There will always be thin spots in the ice. You don’t have to create them. What you have to do is have the budget flexibility for the people who work with you and for you to be able to compensate those individuals in a personal way. And they will give back to you like never before.

Roger Dooley: That’s great, Bob. And we could spend all our time on one of the principles, but thinking about a social proof, one example that kind of stuck out as being sort of unexpectedly powerful was when a car dealer ran salesperson recruitment ads during a prime drive time, because they really needed salespeople because they were selling a lot of cars. And what happened then was kind of a surprise because they definitely got some sales resumes in, but they saw a spike in their actual car sales.

And that was an example of social proof because they cited the reason for needing the salespeople as extra strong demand for their vehicles. They were selling a lot, which is sort of the classic social proof when you do it for customer. “Hey, we’ve got 10,000 customers for this software already.” But the fact was, this ad wasn’t even directed at customers. How did that amp up its appeal?

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Because the customers didn’t see it as that they were being targeted by this ad. That the ad was generated for them to convince them. It was the subtext of the ad. The ad was to get more sales people, because there was a lot of demand for the car as well. That piece of information that came from the side rather than flush in the face was much more credible. It didn’t have any ulterior motives associated with it. It was subtext, and people were much more willing to say, “Oh, this must be true then.”

Roger Dooley: Another example that stuck out as something that really seemed almost too powerful to be true is the example of the person who was involved in negotiations and was trying to go back and forth between two parties. And just changing one word caused a big difference in outcomes and where instead of, “We could have a deal where we will have a deal, if we do these things, or if you do these things.” Instead, it’s, “We have a deal if you do these.” How does that work?

Dr. Robert Cialdini: It has to do with the idea of loss aversion, that people are much more … In fact, the research shows, twice as motivated to seize something in order to avoid losing it, than to gain it. There was a study that I like to cite. Researchers went door to door, offering people an audit of their home to see where they needed, oh, insulation and weather stripping. And so on. And half of them were told, “If you will insulate your home fully, you’ll be able to gain, let’s say, a dollar a day, every day.” The other half were told, “If you fail to insulate your home, you lose a dollar a day, every day.” 150% more insulated under loss language than gain language, right? So people hate the idea of losing something.

Well, this example where you were talking about actually a friend of mine, who’s a divorce lawyer, who said that when she would get near the end of a mediation, she’s also a mediator between the two parties. And they often are in separate rooms because you can’t have two divorcing individuals in the same room. It quickly devolves into shouting matches and so on. They’re in separate rooms. And she would shuttle between the rooms, making offers and conveying negotiation details to them of how to settle the divorce.

And she would come to the end, where very often there was some sticking point. And she used to say to people, “Look. If you will accept this last deal that your spouse offered, we will have a deal. And we will be able to finish the negotiations. We won’t have to go to court.” She said, very often, that didn’t work. She’s like, “Can you help me, Bob? What could …” So what I suggested is, she go with that last offer and say, “We have a deal. All you have to do is agree to this final point.”

And I saw her at a party a few months later. She put her hand on my arm. She said, “Bob, this works every time.” I said, “No, nothing works every time. This is behavioral science. It’s not magic.” She put her hand back on my … She said, “Every time.”

Why? Because if you say to people, “We have a deal.” Now you lose it, if you deny it. What she was saying, “If you do this, we will have this deal, which you get to gain.” And we know from psychology, people are more mobilized into action by the idea of losing something than gaining the same thing.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So let’s spend a bit of time talking about unity, Bob. I think this is kind of an interesting principle. It almost seems like an extension of liking, only more powerful. But instead of being like somebody, we’re part of the same group. But there are a lot of interesting little quirks.

One interesting one was, we have a mutual acquaintance, Scott Adams, the creator of Dilbert. And he has a wildly popular podcast that goes out mostly in video format. And every time he starts with something he calls the simultaneous sip, where he’s got this gigantic coffee cup as big as your head, practically, where he takes a sip and encourages his viewers to do the same. And I always wondered what was up with that. But then after reading the unity section of your book, I realized that there was some behavioral science behind that.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Yes. It turns out that when we perform actions in a coordinated way with others, we come to feel more unitized with them. We feel more like we share an identity with them. So in that study that you were talking about, people watched somebody on a screen take a sip of water, put the glass down, and then do some work. And half of them were told just to watch that. The other half were told to take a sip of water at the same time this person was drinking the water. And then watch them and so on. And then afterwards, they were asked to rate how they felt about those people. The people who, who drank the water at the same instant as the person on the screen liked that person more. Because they felt more at one with him.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that’s wild. And I’m guessing that Scott saw that study. And that’s how he instituted that practice. Because he starts his shows live. You can watch them recorded, of course. But all of the shows that begin live. And such a brilliant use of science.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: You see that in? If you go to rock concerts or any kind of concerts of popular music, the band often tries to get the audience to sing along. “Come on,” and they’ll give them parts to sing. And, “When I say this, everybody says …” Again, they’re trying to get them unified with the band, with everybody together. And research shows that not only does sipping together unify people, singing together does. Song has that because of the rhythms and meter and beats associated with commonality of action.

Roger Dooley: Well, I guess religion is a pretty strong type of unity for many people. And often in services, you see some of those same factors at work where either people are singing together with choir, the congregant, or they are reciting the same prayers together. So really, that’s the same effect there.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Yeah. It’s unified. A dance has the same effects. And it’s interesting that if you go back into our earliest history of cave paintings, rock art, and so on, the depiction that most frequently appears in those prehistoric depiction is dance. People dancing together, moving in unison. So it’s a unifying technology. It’s a social technology that groups have discovered since prehistoric times that gets us together as groups.

Roger Dooley: One of the insights in Pre-Suasion, Bob, that I’ve often used as an example of something that’s so simple, but super actionable. And it mentioned, too, in the unity section in the new edition of Influence, is when you are perhaps creating a new product, a new service or a writing a book, you often go to people, whether they are experts or friends or somebody for some feedback on what you’re doing.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Right.

Roger Dooley: But it’s really important how you phrase that if you want to invoke unity, right?

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Exactly. Of course, it’s a great idea to get feedback from people around you before you advance an idea. But you want those people to be on your side when you do advance it. You want people to support your new initiative or new idea. And the way to do it is not to ask them for their opinion on your idea. Because when you ask for an opinion, you get a critic. But instead, to ask for their advice. Because when you ask for someone’s advice, you get a partner in the process. And the research shows that when you ask people for an opinion versus advice on the same idea, they’re more likely to support it. Because when you ask for advice, you have brought them in in a unifying way with you on the idea.

Roger Dooley: Bob, one last question. We’ve been through a crazy last year with the pandemic. We’re just barely at the one year anniversary, but really hitting home here in the US. I’m curious what you’ve observed in the last year about messaging, about human behavior, that you say, “Wow, that really ties into this part of my seven principles.”

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Yeah. I think what I’ve noticed the most is that the idea of unity, as it appears in political parties, causes people to say no to an idea even though it may be beneficial because the other party has proposed that idea. Because the other party is the one pushing it, or is the one who came up with it. I think when Donald Trump used the idea of getting a fast start for inoculation, right? Democrats weren’t willing … For viruses. Democrats weren’t willing to give him the credit for it. Because it was him. It was the other party.

Now the shoe’s on the other foot. With vaccination, now it’s the Republican hesitancy that is at issue because the Democrats are involved in the rollout. So what you have is these two groups that are in-groups and resisting the out group, no matter what the idea or initiative. It’s really troubling.

Roger Dooley: Well, there is a downside to unity. You point out things like Princeton’s members of the police force. So unity is generally a good thing where they take care of each other, watch out for each other, support each other if they’re in trouble. Even risk their lives for each other. But when it comes to say, protecting a member, a police officer, who is not well behaved, who has perhaps a committed a crime or behaving in a bad manner, then unity suddenly turns negative. And I think that’s true. Not necessarily. That’s just one example. There are many, many examples of where people sticking together too much has a negative effect. So it’s got to be tempered.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: That’s right. I mean, what we have to do is get … The group that we’re thinking of is humanity rather than small sections of it. If we can all think about ourselves as unitized as a species. We have common interests. So if we can all pull together, we will do better. So what we have to do is keep changing the focus from localized in-groups to globalized in-groups.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, Bob, what is the best way for our audience members to connect with you and your ideas?

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Clearly the easiest way is to go on our website. It’s influenceatwork.com. Influence at work is all one word, no spaces, dot com. They can get access to all of the information that we have to offer.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link there and to all versions of the new edition of Influence on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have text, audio and video versions of our conversation there, as well. Thanks for being on the show. And again, congratulations on the new book.

Dr. Robert Cialdini: Well, thank you. I enjoyed spending time with you yet again.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.