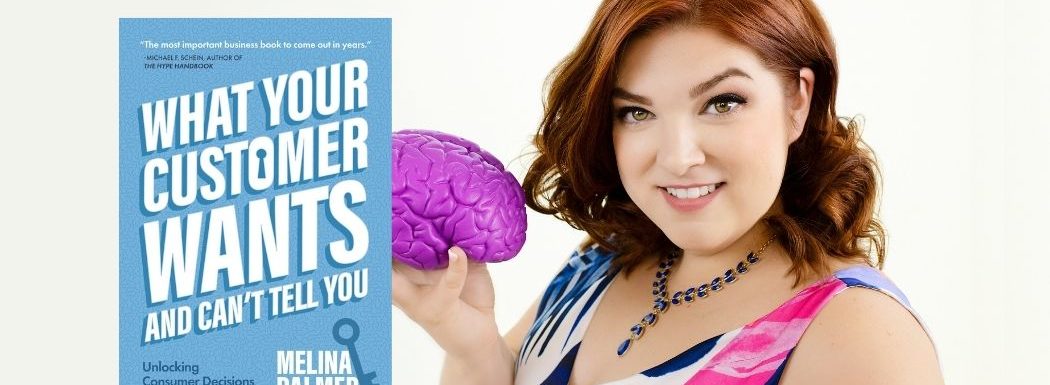

Melina Palmer is the founder and CEO of The Brainy Business, which provides behavioral economics consulting to businesses of all sizes from around the world. Melina obtained her bachelor’s degree in Business Administration: Marketing and worked in corporate marketing and brand strategy for over a decade before earning her master’s in Behavioral Economics. She has contributed research to the Association for Consumer Research, Filene Research Institute, and runs the Behavioral Economics & Business column for Inc. magazine.

Listen in as Melina shares her extensive insights into all the things that customers want but cannot tell us they want, including whether you should lead with the most expensive option when it comes to selling and how to use partitioning to our advantage. We also dive into some of the neuroscience behind behavioral economics and discuss why people buy and how to use that “why” to build better sales, relationships, and messaging.

Learn why people buy and how to use that knowledge to build better sales, relationships, and messaging with @thebrainybiz, author of WHAT YOUR CUSTOMER WANTS. #marketresearch #behavioralscience Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Whether behavioral economics has hit critical mass.

- How priming fits into behavioral economics.

- What partitioning is and how it should – and shouldn’t – be used.

- When it comes to selling, is leading with a more expensive item the better way to go?

- How surprise and delight fits into behavioral economics.

- Pricing tips to encourage conversion.

Key Resources for Melina Palmer:

- Connect with Melina Palmer: Website | Podcast | Facebook | Instagram | YouTube | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Melina Palmer on Inc.com

- Amazon: What Your Customer Wants

- Kindle: What Your Customer Wants

- Audible: What Your Customer Wants

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. Melina Palmer is founder and CEO of The Brainy Business, which provides behavioral economics consulting to businesses around the world. She hosts an excellent podcast, The Brainy Business: Understanding the Psychology of Why People Buy. Melina has contributed research to the Association for Consumer Research and the Filene Research Institute, and she runs the Behavioral Economics & Business column for Inc Magazine. She teaches applied behavioral economics through the Texas A&M, go Aggies, Human Behavior Lab. Her new book is What Your Customer Wants and Can’t Tell You. Welcome to the show, Melina.

Melina Palmer: Thank you so much for having me.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I was struck by something just about a day ago. I was looking at the actual paper edition of the Wall Street Journal, Melina, the weekend edition. And in the op-ed section, there was a lengthy piece by Daniel Kahneman and his co-authors of his new book. And, just one page over was also a column from Dan Ariely. I’m thinking this is the preeminent business publication in the US, and here we have behavioral economics, not in one spot, but within two spots within just a page of each other. Do you think that behavioral economics has finally hit critical mass?

Melina Palmer: I think there’s still some room to go before we make it to critical mass, but we’re definitely on the way. It’s been interesting with my book coming out this month in May. And so Katy Milkman has a book out. Like you said, Kahneman and Sunstein have co-authored a book. There are so many others where you just look and it’s another book, another book, another book, coming out right now. So, I think it is been on the rise for a long time, and people are really catching on, that this is something to pay attention to and listen to, and I’m glad to see it getting more traction.

Roger Dooley: I guess it’s a fine line between competition and also validation of the space. If you had the only book about behavioral economics, then people would say, “Well, that’s kind of an outlier or some weird thing for eggheads.” But when you suddenly see best-selling books about behavioral economics, and that says, “Okay, this is a reasonable space.” And Melina’s book may have something different to offer than the others, which of course it does, because I’ve got it here for our video audience. And it is really a very practical guide to how to apply this technology or the science, unlike… There’s not really that much theory in it. The theory is there, so you can do the research if you want. But it’s a very practical guide, perhaps a little bit different than what Daniel Kahneman might write, because he’s not really a digital marketer or really a marketer of any kind. So I’m curious, Melina, we’ve seen this additional acceptance of behavioral economics in business. Have you noticed an uptick in negative or somewhat unethical uses of behavioral economics, behavioral science thing, what people call dark patterns?

Melina Palmer: Thankfully, I haven’t seen a lot of that and more… I get asked about the ethics and “is it manipulation” on pretty much every conversation that I have, which I’m guessing you’ve experienced a lot of that over the years as well. And to me, what I have found in working with all sorts of businesses, from solo-preneurs up to global corporations, is most everyone is trying to… They work for something they believe in, that they think is a value to people, and they’re doing what they can to help others to find this product or service that is a really great fit for them. They’re trying to solve a need. And while there is a small fraction of people that will do ill with whatever new knowledge they have available for them, I just don’t see as much of that. I think availability bias makes us think that it’s this gigantic percentage of people that are going to take things and use them for ill-gotten gains. But truthfully, I thankfully don’t see much of that.

Roger Dooley: Well, that’s good. I guess the sorts of things that I’ve observed, and I’m not sure they’ve really increased that much over time. In fact, many of these techniques were in use long before behavioral economics was a thing. But things like false scarcity, sales that expire at midnight, and the next day, that same sale is on expiring at midnight, things like adding friction, making things more difficult that you don’t want customers to do, like make returns for example, or unsubscribe but from a subscription that’s going to automatically renew. That, unfortunately, I still see quite a bit of, even with organizations that you would otherwise say are pretty good companies. But it’s a fine line. At what point does simple saying, “Okay, we want to make sure that people really want to make this decision,” suddenly become, “Well, okay. We’re going to make this really rather difficult, so that we’ll convince some people that that’s not worth the trouble to bother changing your mind.”?

Melina Palmer: Yeah. I think there is a lot of benefit that the field is getting its traction, really, at a time where you have an era of social media and where, when people do see those sorts of things, and especially as people are starting to understand the science, being able to say, “You, I know what you’re doing and it’s not okay.” I think that companies have been publicly shamed if they try to do stuff or make things too difficult, that makes it towards really not worth that risk of trying to make it worse. Some do, like you said, the false scarcity or things like that, but I think people, consumers are pretty aware of when that is happening and are not afraid to go complain on the socials if something is out of alignment.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I have been one of these shamers. I try and do my best to shame any examples of either high friction experiences, like unnecessarily high friction experiences, and also things that are kind of a negative use of influence principles. In fact, about a week ago, I aired an conversation with Bob Cialdini and at that point suggested that maybe a #badinfluence would work for that if folks encounter that somewhere, and I’m sure we all do, to call it to the public’s attention, because as you say, there is considerable pressure once a company realizes that they’re being called out on this. And often it’s probably not top management that is even aware that this is being done. I think that in general corporations, top management rarely experiences what the customer does, what a regular customer does. If they need something done, their assistant does it.

And they probably did not order their people to add friction to the unsubscribe process. But somebody’s did an AB test said, “Well hey, if we put this extra step in there, fewer people unsubscribe, so let’s do it.” So anyway, I think that we should exhort our viewers and listeners to do that. If you see stuff that is wrong, if people are misapplying these principles, call them out in public, and perhaps the rest of the community will amplify that. So I have a question for you, Melina. If a business has become aware that, “Okay, behavioral science is a thing. Behavioral economics is a thing. We aren’t really thinking about that at all in the way we are currently marketing to our customers.”, where would you suggest they begin? How can they bake some behavioral economics into their marketing?

Melina Palmer: Well, I think the first step is to get some awareness of how much bigger the field is than you think it is when you first get introduced. So, you read Nudge or Predictably Irrational, or the new expanded version of Influence like you’re talking about, and you have a little piece and think, “Wow, this is amazing. I’m going to go jump in and apply.” If you don’t think about all the associations of the brain and the complexities and understand context and all of that, you can inadvertently set up a test that’s too big, or looking at the wrong problem and feel like it’s not a field that actually works or that it’s not true. It didn’t work for you, something along those lines. And so when a business tries to apply this, the problem I see most often is trying to attack the wrong problem. And or, just again, starting with far too large of a problem that you’re trying to solve when you get started.

So, if you do some smaller tests and then have some understanding of a few basic concepts and how they would go together, then it gives you this ability to start building things together. I used in my book an analogy of behavioral baking. Say, if you wanted to open a bakery, you first need to know what the ingredients are and how they work. Butter, sugar, flour, and eggs can be combined to make all sorts of different things. It could be making cake and cookies or bread. But if you don’t know that you need more flour than sugar or whatever that is, or what the eggs are there to do, if you just throw everything in a bowl, you don’t know what you’re going to make, it’s a big mess. And so if you have a plan and a bit of a recipe to follow, you know how those concepts, ingredients are going to work together, it gives you a safe space to start applying the concepts and testing it out.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I primed you there, Melina, with the word bake into your marketing. So, I figured that’s where you would end up with that. So I have primed you. Why don’t you talk a little bit about priming as our audience might do it?

Melina Palmer: Yeah, absolutely. I love the concept of priming. And this is where… If we have, like you said, a word that you said that brought up, baked in, made me think of my behavioral baking analogy in the book, but also you can do this with smells, with visual implications, with the power of touch. The senses are very closely tied in with priming. And so, something that happens before, whatever the action is that you’re looking to take is, is very, very important. And so if you have an example, let’s say that there was a study that was done, where they had people they were asking to work together and the room, and for some people, there was a briefcase insight. For some, there was a backpack insight. And that study found that those in the briefcase room were more combative.

Those in the backpack room were more cooperative. But of course, everyone said they didn’t even see it. They didn’t even realize there was a bag of any kind there, but it influenced their behavior because they were primed by what it means and what’s associated with each of those things. Backpacks remind us of school and working on group projects and a different type, whereas briefcases are boardrooms and fighting over cash or whatever that happens to be. So those associations impacted the way that their brains approached the problems they were working on and being part of those teams.

Roger Dooley: One concept that I wasn’t that familiar with before I read the book, or at least the terminology, was partitioning. And by the way, I did, of course, read the book because you were kind enough to invite me to write the foreword, Melina, which I appreciate and… Explain partitioning in what, how people can use that.

Melina Palmer: Absolutely. Right. Should or shouldn’t. Yeah. Of course, also, thank you so much for writing the foreword. It was a great honor to have you do that for me. So, love having you been included in the book there, and of course there are a couple of references to Friction throughout the book as well. In the case of partitioning, this is having a separation and how you have these little kind of transaction costs and how it can impact behavior. The example that I like to use is, if you were to sit down with the giant bag, party sized bag of Cheetos versus a bunch, if you had an unlimited supply of little fun-sized bags of Cheetos, do you eat more in one scenario than another? And of course, yes, you do. When you have the large bag of Cheetos, you’ve made one decision, “I’m going to eat chips.”

And then every time you reach back in for another handful, you’re just reinforcing a decision that you already made. And so, keep on eating until you either get a stomach ache or you hit the bottom of the bag, and that’s sort of how that works. Whereas with the fun-sized bag, each time you go to grab another one and have to open it, it’s that tiny little moment of, “Do I need those? Should I get another one?”, separating that into those little multi-decisions, can make it to where someone will make a different choice and we’ll eat less. And so, that’s important to know, and you can use it both where it’s good to have the break points, and sometimes you don’t want to have those break points. So in that space, I give the example of Netflix. And if you had to re-engage every single time that an episode ended, do you want to keep watching? You have often that setting after five shows or something, they’ll say, “Are you still watching?”

But if it was to stop every single time, or there was something that’s reminding you that you’re paying, every single time along the way, it would be a worse experience for everybody. People wouldn’t use Netflix as much. They wouldn’t engage in the same way. So making the single decision to watch a show is a better viewing experience. And of course, it’s better for Netflix to keep people in there, whereas if you are trying to get people to break up whatever habit that they’re working on and having those small transaction costs along the way, can be beneficial, even as simple as encouraging someone to buy smaller bags of Cheetos, if they’re trying to lose weight.

Roger Dooley: Well, I would guess that’s a big argument for auto-renew for any products that have a renewal process, which these days, it seems like nearly everything we buy is sold as a subscription. The more you can have customers on an auto-renew basis, they don’t have to re-decide each time. And again, as long as you don’t make it unethically difficult to unsubscribe, that’s, I think, a perfectly fine thing to do, because there will be many people who simply won’t want to make that extra decision. They, for whatever reason, won’t renew manually, but even if they were finding value in the service or the product and would have renewed otherwise.

Now, loss aversion is something that really underlies so much of behavioral economics. It’s one of Kahneman and Tversky’s initial major findings that humans tend to be averse to losses and the losses are more important than equivalent gains. And one scenario that I really hadn’t thought about in terms of loss aversion is, with a product that may be sold in either, say a basic version or a loaded version with many additional features and benefits and so on, and how should a salesperson approach that kind of a sale? Is it better to lead with the inexpensive item and then build up to the more expensive one, or vice versa?

Melina Palmer: Well, we’re definitely getting into relativity there as well, and some anchoring in our loss aversion example, in which case, there are always exceptions to every rule, but in general, you would want to go with the biggest thing first. That’s the more expensive, with the bells and whistles, and work your way down. So, if you come in and say you’re going to buy a car, and in that experience, do they say, “This is the baseline model and it would be $200 a month. And if you want, these are all the things you can add on, a power door locks and power windows,” and you have to tick tick tick tick tick tick tick your way up on the process? No. What they do is they say, “This is the super amazing version of the car, and this is what your payment would be, $295 a month or whatever.”

And if there is anything, if they may be bulk at the price, then you say, “Here’s the list of stuff. Feel free to get rid of anything that you don’t want.” Then your loss aversion, of course, kind of comes in. You go, “Well, I mean backup camera, for $500, it’s going to be, it’s like a couple bucks a month. I’m going to get $5 a month of value out of my backup camera. That’s worth it.” Whereas, in the baseline model, if you just see that $500 thing you think, “do I really need that? I don’t have one now. It’s not worth it.” So that context and association of whether you have taken perceived ownership over it already in this model, and then you look at the small costs per month versus adding it on where you kind of just see the whole big thing, loss aversion is a real big player in that, for sure.

Roger Dooley: I think that that’s another area affected by bundling too. Typically, when companies are selling cars, they don’t try to avoid the single little upgrade feature and sell packages or the luxury package or the ultra luxury package, because one thing that does is, first of all, it makes life simpler for them. They don’t have to build 10,000 different versions of the same model, but also because it sort of disguises the value proposition of each item.

If the leather seats would cost, be a $2,000 option, and somebody says, “Well, man, my leather couch only costs me $1,000. That doesn’t seem like much of a deal for a few little leather surfaces on the front seats.” Well, when it’s all part of a bundle, it just seems like, “Okay, I’m paying an extra few thousand dollars for this pile of luxury I’m getting here that has the heated seats and the leather and a few other fancy items to go.” So, I think that was maybe researched by Ariely or Loewenstein, I’m not sure, but it’s selling any kind of complicated packages like that, I think there are so many nuances. And you mentioned a few others too, via setting a high anchor price and so on.

Melina Palmer: But something that doesn’t have to be a huge car or something along those lines that also kind of looks at this partitioning pain of paying aspect we were just talking about is, I have an example in the book of, I was needing to buy a razor holder, little thing for the shower, and it was $6.99, which I was fine with. But it was $3.99 to ship it to me. And I know this thing weighed less than an ounce. You could ship it for 50 cents. And I agonized over this choice for three weeks, which is ridiculous because I needed the thing. I actually knew the person that owned the company, but it was just, oh, I just don’t feel good about it. And I was looking at things on Amazon. Maybe I should do it this way. If that extra decision by partitioning and separating out the fee from this process made it to where I wasn’t really ready.

It took a long time. And if it would have just been $9.99 or even $10.99 with free shipping, I would have bought it, no problem, and been very happy with the experience. But my overall feeling about the entire brand is now tainted by this one tiny aspect, this extra moment where it felt like they were really gouging me on shipping, which I know probably has nothing to do with them, but it just felt bad, and everything else became this big problem. At the beginning of the book, I use a quote from Peter Steidl, that “a brand is a memory”, and it’s that same, I can’t unlive that moment, and it’s impacted every decision I make with that particular company. And whenever I think about them now, because of just that one little moment that they potentially don’t even realize, is a problem.

Roger Dooley: In my Friction book, Melina, I’ve got a little section that kind of provocatively titled Delight is For Dummies, and talking about how there are certain things that delighting the customer doesn’t do, or isn’t quite as powerful as doing some other things like making things incredibly easy. But it’s really not always true. And it’s meant to be a bit of a provocation there to get people to read what follows. And it’s based on some research from Gartner about how an effortless experience is the thing that really creates loyalty. But I do think that delight is a really important factor. Talk a little bit about delight and how it fits into your work and your book.

Melina Palmer: Yeah. So I think in the space of surprise and delight, and there’s a chapter about it in the book where it’s talking about how delight is needing to have a lack of expectation and delight really does drive loyalty, which is something that’s very profitable and important for businesses. And looking at ways, if you’re trying to get away from this question of “is it manipulation and whatnot?”, if you’re looking at ways to be delighting your customers and have them have this really enjoyable, wonderful experience that they want to go positively tweet about, you need to be in a space of where you’re providing things that are unexpected and in a positive way. And thankfully, because of some of the brain chemicals going on, there’s a lot of dopamine that can be released when you have that anticipation of “am I going to win something?”, versus having to give everybody whatever the delightful thing would be.

And then you end up with an issue of expectation and it’s not delightful anymore. So for businesses, it can actually be cost-effective to do a contest or something along those lines. They’re just random giveaways for people that follow you on social media or whatever that is, to where you’re able to be in this unexpected space and doing something that they enjoy and can be just excited about and get delighted if they win. I give the example where Heinz ketchup did ads with Ed Sheeran and created Edchup, which seems super weird, except apparently Ed Sheeran really loves Heinz ketchup. He has a tattoo of the Heinz logo because he just loves Heinz so much.

And so, for an anniversary special, they came out with these limited edition bottles where the tomato on the bottle looks like Ed. It’s got little leafy hair and glasses of Edchup instead of ketchup. And they shared about it on social media and all these great followings and people excited and wanting to go get their limited edition bottles of Edchup, which is just ketchup. But it was a very delightful experience for him as well, which is important because he loves that brand so much. And then all of his followers know that he does and then they love it too. And it’s just delightful and people share and feel like they want to be part of that conversation.

Roger Dooley: I guess that’s a true measure of brand loyalty, if your customers have it tattooed on their body. And I can’t think of too many brands that really incite that kind of loyalty. Harley Davidson maybe, sort of an overlap with tattoo users there too. But also maybe Apple, I’m sure I’ve seen a few Apple tattoos out there, particularly before Apple became something that everybody had with the iPhone, back when it was the Mac and kind of a counterculture thing almost. But yeah. That’s… Definitely, if you can incite that kind of customer feeling, you’re going to be in business for quite a while. And I think there’s probably another kind of delight too, that is, maybe not necessarily a complete surprise, but I know… A while back I had Jay Baer on the show and his co-author Dan Lemin, and they talked about DoubleTree hotels, where they give their customers a nice big cookie when they check in, and they actually saw several cookies when they checked in.

And these are really good cookies. I mean, these are bakery-quality cookies, are very fresh, very tasty. And the first time you show up at one of their hotels, you’re definitely going to have that surprise delight factor. And even after that, though, it’s a self-reinforcing thing that you go back there. I’m sure there are customers who make that choice. If they’re one of these typical sort of hotel meccas where there’s six similarly priced hotels, all within about a one block radius, people will choose the DoubleTree to get the cookies. And probably the only risk factor there is the DoubleTree is now locked into those. If they ever stopped doing cookies, they would have a customer revolt.

Melina Palmer: Yeah. I actually talked about this a little bit and wrote a post somewhere, I forget, but that was talking… Early pandemic days when everybody’s sort of, “What do we do?” And of course hotels were suffering and how can you stay top-of-mind for people in this process? And so DoubleTree gave away, for the very first time ever, their very secret chocolate chip cookie recipe, so people could make it at home, of saying, “We know you’re probably missing these, business travelers or whatever, so you can have the joy of DoubleTree, while in the comfort of your home. And we look forward to having you back with us when we can,” or however they messaged that.

And that was a delightful thing for people, and as everybody was really baking a lot during pandemic, and you get to try this great recipe that people love, and it builds this additional association with the brand, and you get some Ikea effect in there. All this goodness that can come from just giving that little piece, reciprocity, there’s a lot of concepts happening in that space, but it helps to reinforce their brand, even when people couldn’t stay with them.

Roger Dooley: I think that’s a good example too, Melina, that what seems like, oh, just a marketing gimmick, “Oh hey, let’s give away our cookie recipe and maybe get a little bit of social media,” really has quite a bit of behavioral science baked, I have to say it, baked into that, with all those different things that you mentioned. All those principles can be powerful alone, but this one really invoked multiple principles. So it’s really a fantastic example. We’re just about our time, but I’m curious whether you have a few quick pricing tips for our audience. I know that there are a lot of pricing topics in the book. What should somebody look at for pricing? Just maybe a couple or three.

Melina Palmer: Yeah. Yeah. So, would say that when it comes to pricing, everything that happens before the price generally happens, it more matters more than the price itself. And I use this example, funny enough that it’s not about the cookie. It’s how I’ve talked about it when I have episodes and things on this, but that’s the scent of the cookies priming and drawing you in and making your subconscious brain ready to buy. You can use that loss aversion the way you frame the message makes an impact. And so, one of the biggest things where I see businesses go wrong when it comes to applying pricing is getting really focused on the exact number of the price. And this really is an issue of bikeshedding, in where you think, “This is the most important thing, and until we figure out our exact price, we don’t have to think about any of the… We can’t even begin to think about these other things yet, because this is the most important thing.”

If it’s going to end in a five, a seven, a nine or a zero, and what that perfect price is going to be, in reality, research is pretty much… If you’re a gift or a luxury item, you end on the even number. If you are trying to be a discount or associated with something that’s a deal, then you can end with something else, pick whatever you want. Nine, seven, five. It doesn’t really make that big of a difference. Move forward. And then the strategy of, what do you want people to do? What’s the best product or service that you are trying to feature? How do you use that anchoring and relativity to showcase it as the best option for people, that thoughtfulness is all more important than that specific number.

Roger Dooley: Melina, where can our listeners find you and your ideas online?

Melina Palmer: Well, yeah, you can find me on all the socials, as TheBrainyBiz, B-I-Z, or just Melina Palmer on LinkedIn. You can also go to my website, which is thebrainybusiness.com, which has The Brainy Business podcast, links for my book, What Your Customer Wants and Can’t Tell You, and all sorts of other great things. We have a community for everyone that’s interested in behavioral economics to just get together and connect and chat and network, just a free space called the BE Thoughtful Revolution that you can get to there as well.

Roger Dooley: We will link to all of those places on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and we will have audio and text versions of this conversation there as well. Melina, congratulations on the book. I was glad to be a tiny part of it, and stay safe and good luck.

Melina Palmer: Thanks so much, Roger.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.