Before he became internationally recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on body language, Joe Navarro was an eight-year-old refugee fleeing communist-controlled Cuba. In America, as a non-English speaker, he survived by observing others, eventually going on to lead a career as an FBI Special Agent studying and applying the science of non-verbal communication. From there, he went on to spend a quarter-century with the FBI, pursuing spies and other dangerous criminals across the globe.

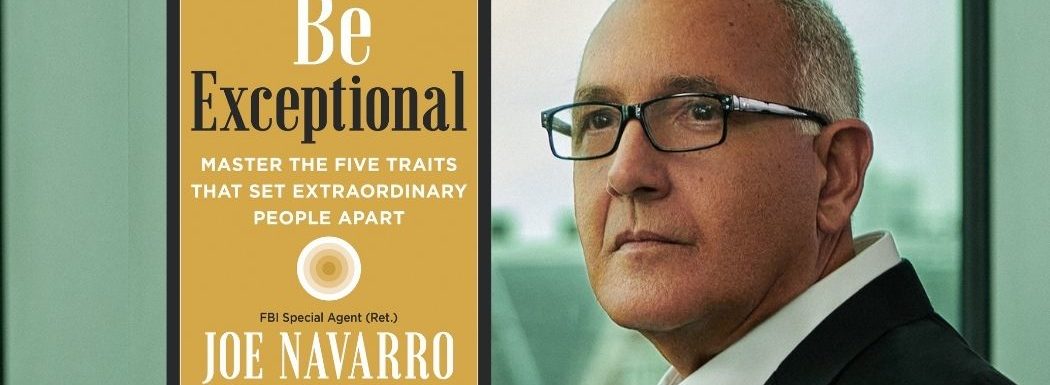

In this episode, Joe describes how he has collected his hard-earned lessons in his new book, Be Exceptional, distilling his experience into five principles that outstanding individuals live by. He also shares why observation is the key to innovation, what the pandemic has taught us all about body language and facial expressions, and where he sees the future of business and personal communication going.

Learn how YOU can BE EXCEPTIONAL from FBI #bodylanguage and #nonverbal communication expert Joe Navarro, a.k.a. @navarrotells Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The challenges the last year presented due to the pandemic.

- Where Joe sees the future of communication headed.

- The communication attribute that makes for the best business person.

- How we can each become better observers.

- The benefits of making observation part of your daily routine.

- Why observation is key to innovation.

- How to translate observation into beneficial action.

- The importance of psychological comfort in life and business.

Key Resources for Joe Navarro:

- Connect with Joe Navarro: Website | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

- Amazon: Be Exceptional

- Kindle: Be Exceptional

- Audible: Be Exceptional

- Amazon: Small Data: The Tiny Clues That Uncover Huge Trends

- Sizing People Up with Robin Dreeke

- Chris Voss on Negotiation: A Radical New Approach

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. In the US, the FBI, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, has always had a strong emphasis on science in general and psychology in particular. Joining us today is Joe Navarro, a retired FBI special agent, and an expert in nonverbal communications. These days, instead of chasing bad guys, Joe teaches business people how to communicate better and be more persuasive. His new book is Be Exceptional: Master the Five Traits That Set Extraordinary People Apart. Welcome to the show, Joe.

Joe Navarro: Roger, it’s a pleasure to be with you and thank you for having me.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, for a guy who specializes in nonverbal communication, I’m curious what challenges the last year presented because we’re all on Zoom, in person, we’re wearing masks and such. How has affected the way you think?

Joe Navarro: Well, that’s a great question. Me it didn’t affect all that much because while most people focus on the whole face, I focus on things such as the neck, the shoulders, the muscles above the eyes, for instance, the arching of the eyebrows when we greet, hand gestures and so forth.

One of the things that this last year taught us is how many people complained that they felt that they really couldn’t understand others, they felt there was a deficit because they couldn’t see them. And so for the first time, you have this overwhelming testament to the importance of body language that we depend so much on seeing that friendly face, that smile. And then the question was, “Well, what do we look for when the face is covered,” and so forth. And something so simple as the gestures that normally we would use out here had to be brought in, as broadcasters have learned, into this little small space.

And so it was a challenge for a lot of people, but I think it’s a testament to how important body language is to effective communication.

Roger Dooley: I’m curious in particular about Zoom, because it looks like Zoom communication or any kind of remote conferencing and so on is going be part of work for the foreseeable future. We’ve got many people now who are saying, “Well, I’m just going to be 100% remote,” and some companies are going with that, or, “We will be some portion of the time remote.”

And it just seems like Zoom inhibits certain types of communications. Certainly information can be transmitted just as well. If I want to update you on the status of three project elements, I can probably do that pretty well over Zoom, about as effectively as I could in person, but there’s a whole other dimension to that communication that’s lacking. If I appear to be looking at you trying to establish eye contact, I’m actually looking into a camera and not looking at you unless you happen to, or unless I happen to have a beam splitter. And I can’t really see what the rest of your body is doing necessarily. Typically, while some people are pretty good at using say hand gestures as part of a Zoom conversation, others, not so much, and it depends on how far you’re focused in and so on. How do you see this changing business and communication?

Joe Navarro: It’s a great question and it’s one that I actually, because I was in the middle of writing the book during the pandemic, I could literally comment, in real-time, “These are the effects we’re having.”

So let’s take the overarching thing that we’re looking at is, undeniably, the future will be hybrid. Businesses have learned that an X amount of people enjoy talking to each other and seeing each other, many more people will be working from home than ever before. There are companies that are now coming out with these little mini pods that you can buy for your home so you have your own little private setting so you can do virtual communications in a quieter, more tasteful environment.

All these things, nobody has a picture of the future. We know it’s going to be hybrid. The question is how much of it it’s going to be?

The other thing we learned right in the middle of the crisis was, I mean, we went from maybe 5% of the population using virtual communications to a large portion of workers using it, is that we had to transition from being just present in meetings, to doing presentations, to going to that higher element, which is how do we do a performance? So as I’m looking at you, you have this beautiful background, it’s well lit, your microphone and your speakers are working optimally.

Most Zoom and virtual calls, one of the things that happened was is we had poor production quality, bad lighting, bad microphones, everything from people moving behind us to animals jumping on us. And that’s cute and adorable, but in the end, businesses were saying, “Well, wait a minute, you’re representing us, so you need to be at this higher level of production quality,” what we now call performance. And we really weren’t prepared for that. And many people still haven’t bought into that, not realizing that people will only tolerate poor production quality for so long.

Roger Dooley: You have a funny story in the book about how, in your early days of firearms training at the FBI, the instructor asked, “Who here has experience?” And you were quite happy to raise your hand and say that you had some previous experience. And then you found that you pretty much had to unlearn everything you had learned to learn how to do it right or to do it the FBI way.

Joe Navarro: Yeah. Thanks for bringing that up, because this is one of those great stories where you’re young, you’re a little cocky, and you think, “Oh, well, I’ve already had a police training,” because I was a police officer in Provo, Utah at the Brigham Young University. So you think, “Well, I’ve had firearms training,” and there was five other guys in class that had training in the military. So we’re looking at each other like, “Well, we got one up on everybody else.” The instructor said, “Not so fast. We got to retrain you guys because we don’t know what junk you’ve learned.”

And so we were taken apart and said, “You have to relearn everything, everything from how you place your hand on the weapon, how you clear your jacket, how you draw that weapon up,” everything had to be done.

And of course we didn’t call it that back then, but we’re talking about it, and I know you’re very familiar with this, is the concept of myelination, that we need to do those best practices all the time and that we can strengthen, make those synaptic connections robust by doing them slowly, but perfectly, and then working on the timing.

And it was interesting to see that those who had never held a weapon before learned it quickly. They learned the best way. And for those of us who had learned all sorts of terrible ways to handle weapons, now had to recreate these things. And it’s a reminder to us that well-meaning people come into our lives and they share things with us, but I’ve seen it with people that were learning the piano, I’ve seen it with people who learned to play tennis, people were trying to be helpful, but it’s a reminder that when someone comes along, a good coach, a good mentor and says, “Look, let me help you because you’re not doing it to the best of what we know,” that we have to be humble and say, “You know what? You’re right. Teach me how to do it, and then I will rehearse that and myelinate those synapses so that they become robust in this new way.”

Because we can actually have very robust synaptic connections in doing bad things. And so it’s a matter of really learning. Yeah, that was a real humbling session for us.

Roger Dooley: Well, I wanted to actually take that story in a little bit of a different direction. Although what you’re talking about with the myelination is that old saying, neurons that fire together, wire together, and that the more you reinforce a particular pathway, the more automatic it’ll be, but where I wanted to go with that too is you had been studying nonverbal communication for 10 years before you joined the FBI. I’m curious whether you had any kind of a similar experience with that, whether you were able to put those skills to use, whether you had pushback or how that went?

Joe Navarro: Oh, well, yeah, so for reasons unbeknownst to me, I just developed this interest right out of high school and into college, and there weren’t a lot of books back then on body language, but I became fascinated by the limited work that existed, for instance, in anthropology, in sociology and in psychology. And so I was trying to latch on to that because I came to the United States as a refugee, and not speaking English, I had learned to have great confidence in body language. Body language never let me down. I mean, if somebody doesn’t like you, you pretty much can figure it out from the way they look at you, talk to you, turn away from you and so forth.

And then of course when I got into law enforcement, I realized that’s all we do. As we said before in our conversations, Roger, in law enforcement, all you are is a paid observer. I mean, television makes you out to be this guy. You got weapons and you can jump through buildings and so forth, but that’s not reality. The reality is, and you’ve had some of the best FBI agents that I ever worked with, Chris Voss, Robin Dreeke, and others, it really is about observation. Whoever’s the best observer is going to be the best agent and is going to be the best business person unequivocally.

So as I started to collect information from all the fields, because nonverbals is an area that’s not dominated by any one ology, psychology, sociobiology, anthropology, ethology all contribute, I started to find that there was almost nothing out there that would help me in law enforcement. There was a lot of misinformation. I mean, basically it was a lot of crap that if somebody talks and touches their mouth, they’re lying, or if they scratch their ear, I mean, just absolute nonsense.

And so once I got into the Bureau and I began to apply it, and you’re right, there was some resistance from the people we affectionately called the dinosaurs who said, “Well, that’s not really science,” or, “We don’t need that,” or stuff like that. By the time that I had begun to use it and to explain the efficacy of its use, it became something that became more respectful.

And then of course we hired the best. We hired Paul Ekman. We hired Bella DePaulo, Judy—and all sorts of professors that would come in and teach us. But the one thing that they couldn’t teach us is what we would see in vivo. These are all researchers, but they’d never talked to a spy. They’d never talked to a terrorist. They’d never talked to a bank robber, and that’s where we could contribute to the literature.

And so when eventually the Behavioral Analysis Program was created in the National Security Division, I in effect became the FBI’s expert on body language, which included not only how to observe, but then what do we do with that? What do we do with that information?

And that’s what this book is about. A lot of people can say, “Oh yeah, I saw the lip compression,” or, “I saw that there’s a little sweat between the philtral columns.” That’s great, but what do you do with that? And that’s what most people can’t answer, is do you tell the person, “I’m seeing this behavior.” How do we use that to assess others?

And so when it comes to that all important thing of harmony and getting along with others and communicating effectively, we have to be able to dissect, interpret, decode each other in the same way that perhaps no one does it better than a parent or a mother with a baby who can understand, “Oh, he needs to go to the bathroom,” and so forth, but that only takes place because of observation.

And so it was important obviously in the FBI, but later when I retired, I think that’s why my career post-Bureau took off is because businesses began to see, “Oh, this translates exactly into what we do.” How do you hang on to your customers? How do you read a patient that maybe is holding something back? There was resistance, and there will always be resistance, but its efficacy is really unequaled.

Roger Dooley: Joe, how do we become better observers? It seems like today, we have so many distractions. A few years ago, if I were sitting alone at say an outdoor cafe table, I’d probably be looking at people, looking at birds, traffic, seeing what’s going on around me. Today, my immediate instinct would be to pull out my phone and amuse myself that way. And I think that’s pretty much what everybody does. If somebody is standing in line at Starbucks and they have 10 seconds, they pull their phone out. How can our audience become better at observing?

Joe Navarro: That’s a great question. And you’re right. We transitioned, in the matter of three to five years, we literally transitioned from being a species, speaking as an anthropologist, who observed the world and would comment on the world and would say, “Oh, look at her, look at him, can you believe what he’s wearing?” that type of thing, to all of a sudden now, it’s go to the screen, go to the screen.

What’s happened, as you say, it’s affecting our ability to observe. And let me say, it’s affecting us in critical areas. In law enforcement, we have law enforcement officers who are coming on board who are not as good at observing as previous generations. And from talking to doctors, saying that we now have doctors who are just switching from every day conversations where they normally would interact with each other and nurses and patients, to, “Well, we got to get this on the tablet because it’s got to be an electronic file,” and they’re hardly making any eye contact. And of course that contributes to lack of eye contact. If you’re a doctor and you’re listening, lack of eye contact with your patient equals lawsuits. I’ve been there. I’ve testified.

Now, how do we become better observers? One of the things that I try to teach, and there’s a large section that I cover in the text, and that is how do we go back to that magical when we were six, seven years old and we had that curiosity, that benign curiosity, and then later, it’s taken from us because people say, “Well, don’t stare,” or, “We got to move along.” “Yeah, but I want to watch that alligator.” “No, no, we got to go.”

We have to train ourselves, and the way that I do it is I compel myself to the minute I walk outside, is to force my eyes to engage the environment, and even my nose because I will take deep breaths just to see, “Okay, what am I smelling?” and so forth. But using that, forcing myself to walk down the street and say, “Okay, what are the new cars that are on the street? Why is that mailbox open when all the other mailboxes are closed? Why is there dirt around the tires of this vehicle?” it’s not so that I will solve crimes, it’s to force myself to become observant so that I never get lazy.

Now, people say, “Gosh, Joe, if you do that and you’re in a crowd of people and you’re picking out who’s got the yellow dress and who’s got the blue suit and whose tie is loosened, that’s a lot of work.” It’s a lot of work the first time you do it. It’s a little less the second time. But by the time you get to my level, it’s like software that runs in the background.

I don’t sit there and sweat what I’m observing, but if you ask me, I can break it down for you. I can tell you the blink rate of everybody in front of me. I can tell you where the exits are. I can tell you everything, but only because I have trained myself to observe. And so rather than becoming more difficult, it actually becomes easier.

And so if you’re in human resource and that person walks through that door, you need to be able to do that quick scan that says, “This person needs my attention because they’re struggling right now emotionally,” and they may be trying to restrain it, most of us do, but they’re breaking apart. Something so simple as they walked in and their interlaced fingers are like this or the mentalis muscle is pulling upward, put everything down. These are reserved behaviors. This person is struggling. I need to make time for them because that’s what’s needed.

That’s what observation allows you to do. That’s on the human side. On the other side is you can’t innovate unless you’re a good observer. You can’t possibly innovate if you’re not a good observer. If you don’t see, “Oh, we can change that, we can make that better,” it’s not going to happen. As I studied exceptional people, one thing they had in common is their extraordinary ability to see detail, and you can only do that when you apply yourself.

Roger Dooley: It reminds me a bit of Martin Lindstrom, who’s been on the show several times. He wrote a book called Small Data about going into hundreds or more people’s homes in different cultures and just observing and drawing conclusions from little things like refrigerator magnets. And it’s pretty much exactly what you’re describing. Assuming that we can become better observers, at least we start paying attention to what’s going on instead of keeping our nose in our phone or listening to podcasts like this one, how do we translate that into something useful, into beneficial action?

Joe Navarro: Well, it’s very easy. First, by the way, when we begin to train ourselves to observe, one of the things that I point out is also reward yourself. Find a way to reward yourself because you’re going above and beyond. Let me tell you, there’s a lot of people that you ask them, “Do you want to be average?” nobody says they want to be average. You say you want to be exceptional? Yeah? How are you going to do it? How are you going to do it? What, you’re going to tell me you’re going to work harder? Stop right there. That’s not exceptional. You’re going to have a heart attack. Exceptional, you have to do certain things. And that’s what I talk about, is what are those things?

So you asked, “Well, so I become a better observer, where does that get me?” Well, you and I, as humans, at any moment are transmitting our thinking or emoting needs, wants, desires, preferences, fears, or concerns. Whoa, think about that one for a minute, needs, wants, preferences. Like how should I talk to Robin or Chris? Or how do I talk to Roger? Because each human is different. How do I communicate empathetically? How do I sense that you may have apprehensions, concerns?

Roger, you’ve been doing this a long time. You make it look easy. For a lot people, they may be nervous to come on your show. So how do you assess for that? And that’s the beauty of observation, is that this is part and parcel of being humane, to be able to assess for those, just like a baby, those needs, wants, desires, fears, preferences, and concerns. And if you can do that, you are miles ahead. You are orders of magnitude more effective in life, be it at work or in relationships, because now you’re in that exceptional realm where you are so in tune with the person in front of you that you can both communicate more effectively, but you can also act more quickly and more ethically.

Roger Dooley: One story that stuck out in the book I think was the Ritz-Carlton general manager who you were having a conversation with, and suddenly he said, “Oh, wait a minute,” because he had spotted a couple who got off an elevator and look just a little bit off, like there was something about their body language that they didn’t seem like they knew where to go or there was something wrong. And he was A, observant enough to catch that, something that probably most people would not have noticed, and then immediately interrupt what he was doing and act on it. And that’s one small indicator of why Ritz-Carlton has such amazing service.

Joe Navarro: Yeah. I’ll never forget it. I was there for training, a beautiful facility in Sarasota, highly recommend it. We had broken for lunch and we were wondering where we’re going to eat. And some people were going to join us. And we were just standing there in the foyer. And this couple comes out, and the manager just… I mean, talk about being able to observe. I mean, he just looked over like a little quick look and he said, “Just a minute.”

Now, I’m pretty good at this, this guy was great. He went right over to them and he said, “How can I help you?” And they were visiting from out of the country and they couldn’t figure out how to get to the because they felt like with their bathing attire, they shouldn’t be walking through the lobby. So he took them right to it and comes right back to me.

But he said something that is so important. It’s so important in business and it’s important in relationships, and it was this, “If I am running a hotel and I have to wait for the customers to come all the way from the elevator to the front desk to ask, I have failed.” Think about that. Think about that. Think about how many places you’ve checked into where, to get help, it’s like everybody’s standing around clueless. And yet you go to these exceptional locations, and I’m thinking of, I have a favorite hotel in New York. I mean, everybody just immediately comes to you and says, “May I be of assistance?” the minute they sense that you need assistance.

And this goes right in line with the ample research that has been done with babies. At 14 months, a baby will favor even an inanimate object that does pro-social things for them more quickly.

And so when I coach businesses, I said, “If your valued clients have to jump through all these hoops to get to you, you’re failing them, because you should be moving as quickly as you can towards them so that you create this wonderful thing called psychological comfort.” Because whoever provides psychological comfort, that’s who wins. That’s who wins in life and in business.

Roger Dooley: Another story in the book, Joe, is how running, you found the, well, now, ex-FBI director Louis Freeh, joining the running group of agents or trainees. And that isn’t something you’d see in a lot of organizations, where you’d find the CEO jogging along with you. And it kind of ties into something, a long-term principle called management by walking around, made popular by Tom Peters in his In Search of Excellence book, about how simply not interacting with senior leaders only, but getting around and talking to everybody in the organization is important. So how do you find that fits into your philosophy?

Joe Navarro: It’s a great philosophy. As agents, the FBI, it’s not like it’s paramilitary, but we have a hierarchy. We have agents, we have supervisors, we have special agents in charge, unit chiefs and so forth. And to get that message up to the director is convoluted.

Louis Freeh, who, bless him, he understood what it was like to work with agents because when he was in the Manhattan US Attorney’s Office, he worked directly with agents. And so he knew how hard it was to work on an agent’s salary and so forth. And he would come to Quantico on Friday, which was graduation day, but he would leave his home at 4:00 in the morning to make sure that he would hit where we would run between 6:00 and 8:00. And we’d be running along, and all of a sudden, and we still don’t know where he parked, but he would just come up behind us. And all of a sudden I’m looking to my left and here’s the director of the FBI. I can’t imagine Hoover doing this. And just, he’s running with us.

And whatever we’re talking about, he’s talking about that. And he made sure that there were no hangers on from headquarters. He didn’t want to have any deputy directors or assistant directors or any of these people interfering with that, as you said, that direct line of communication between himself as a director and that agent who is doing the best that he can with the resources and so forth. And it was a great lesson to me of the power of direct communication, of the power of direct observation, and clearing and making yourself accessible. And I think businesses that do that, leaders that do that, do themselves a great favor. They really do.

Roger Dooley: I think that in today’s organization, if a senior executive would just go out to somebody’s workstation elsewhere in the building or in a field office or something like that, and also, as you say, employ those enhanced observation powers, because chances are the person that one is speaking to you might be a little bit intimidated or nervous about what they could say or what they shouldn’t say, they don’t want to get in trouble, but using those enhance observation powers, they can come to some pretty important conclusions about maybe what to ask next, what to talk about, and maybe what actions might be helpful for that person or for the organization.

Joe Navarro: Absolutely. Roger, I talked to one executive who said, “Just from walking around, I’m walking around and I see this little work area. And I notice that my employee there, she has a call-out sheet of five names, and these are the backup babysitters in case she’s running late.” And he said, “Just seeing that list that was posted for her,” he said, “you know what? I need to spend some time with her and see what she goes through. Because we throw things around and say, ‘Well, can everybody stay around for an hour?’ But for her or him, they’ve got to scramble and find somebody that will go to the school and pick up their child.” And he said, “That observation alone helped me to create a program where the first priority was the control of time for families,” so that this immovable thing called, hey, school’s releasing, somebody has got to pick up this child, and the fact that many schools now, even private, well, especially private school, says, “If you don’t pick up that child within the first 15 minutes, we start charging you.”

And he said, “That made such a difference, but the biggest difference it made, it let the employees know that the boss cared.” You think that person is going to go to another job? No, they’re going to stay there. Why? Because somebody cares. Somebody’s creating psychological comfort and they did it by observation. And that’s the importance of observation, is that when you train yourself to pick up on the little things, you’ll be able to achieve major things.

Roger Dooley: Such a great point and probably a good place to wrap up, Joe. Joe, how can people find you and your ideas online?

Joe Navarro: Well, thank you. They can reach me at joenavarro.net or jnforensics.com, but my books, most booksellers have them. Certainly Amazon has them. HarperCollins has them. Major book dealers has them. And I do try to answer everybody’s emails. I think I’m fairly easy to get ahold of.

But I want to thank you, Roger, really for what you share, because I think what you share with the public is really important and it’s that humanity that is so powerful. So thank you.

Roger Dooley: Well, thank you, Joe. And we will link to all the various places that you mentioned, and we’ll also link, you mentioned Robin Dreeke and Chris Voss, both past guests on the show. We will link to the episodes with them for any of our FBI junkies. And everything will be on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And there will be audio, video and text versions of this conversation there too. Joe, thanks for being on the show.

Joe Navarro: It’s my pleasure. Thank you. Thank you for inviting me.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.