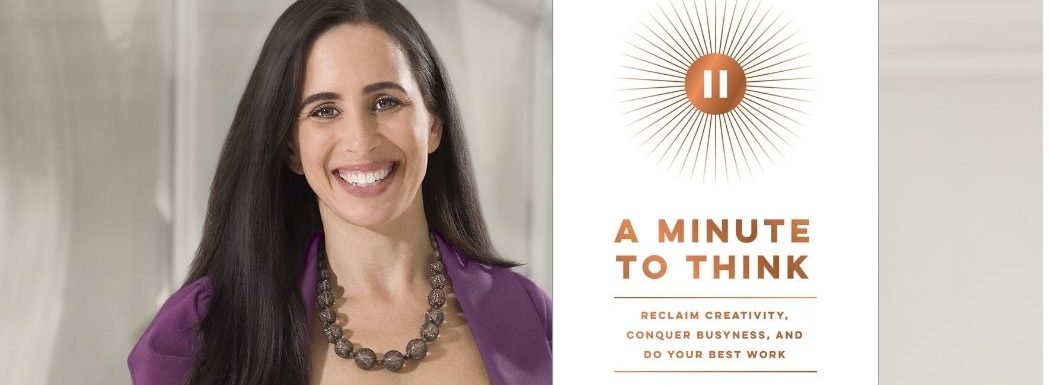

Juliet Funt is a keynote speaker and advisor to Fortune 500 companies. She’s the founder and CEO of the efficiency firm Juliet Funt Group and an evangelist for expanding the potential of companies by unburdening their talent from busywork. She has also put her insights into a new book, A Minute To Think: Reclaim Creativity, Conquer Busyness, and Do Your Best Work.

Listen in as Juliet explains what white space is and why it is so important to enhance productivity in the workplace and get away from the hustle culture that has so many of us feeling burned out. She also shares some of the small ways that white space can be incorporated into your day, why we need to break the assumption that white space is only for recuperation, and tips on how to get away from living in your inbox so you can be less frazzled and more productive.

Learn how to create white space in your day and cultivate productivity with @TheJulietFunt, author of A MINUTE TO THINK. #productivity #creativity Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The importance of space in the cultivation of productivity.

- The definition of white space and where the term came from.

- How to begin creating white space in your schedule.

- How to make white space intentional in your working life.

- The signs that we are not getting enough white space in our day.

- What hallucinated urgency is and how it actually gets in the way of work.

Key Resources for Juliet Funt:

- Connect with Juliet Funt: Website

- The Busyness Test

- @thejulietfunt

- Amazon: A Minute to Think

- Kindle: A Minute to Think

- Audible: A Minute to Think

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence, I’m Roger Dooley. In Friction, I wrote about Parkinson’s law, which says “work expands to fill the time allotted to it.” My focus is on bureaucracy, but the rule applies to most aspects of a business. Even when we are extending the time of individual tasks were filling empty space in our schedules with other tasks and activities or other people are doing that for us.

Today’s guest, Juliet Funt, has a solution. Juliet is a keynote speaker and advisor to Fortune 500 companies. She’s the founder and CEO of the Efficiency Firm Juliet Funt group. She’s an evangelist for expanding the potential of companies by unburdening their talent from busywork. Good news for us, Juliet has put her insights into a new book, releasing on August 3 and available for pre-order now. A minute to think, reclaim creativity, conquer busyness and do your best work. Welcome to the show Juliet.

Juliet Funt: Thank you. We did it, huh?

Roger Dooley: I guess so. I guess so.

Juliet Funt: I’m excited to be here.

Roger Dooley: We had a tech issue, but fortunately, our audience does not have to deal with those. So I was curious Juliet, I’ve only known one other person with the name Funt and this is probably a dated reference for many but in the TV show when I was a mere boy, there was a TV show called Candid Camera. It’s kind of an interesting pre-configuration. An interesting premonition of what marketers would like to do now and film people doing things without their knowing it, but in this case, it was done for laughs. There have been millions of imitators since, but the host of that show and creator of that show was Allen Funt and I thought I’m sure she gets told all the time, “Boy, you must like Candid Camera,” and it turns out you can explain the relationship to the show, Juliet.

Juliet Funt: Yes. Actually, he was my dad. Everybody thinks he was my grandfather because he was a lot older, but yes, I grew up listening to the tales of the very first ever reality television show. And this was

the precursor of any time in all of recorded history that a person who wasn’t an actor is put on camera that seeded out of the Candid Camera Legacy from taste-testing commercials to reality television shows to a lot of versions of it that my father would really hate if he was here to see it, but it was a kinder time when the very, very first show started and that was Candid Camera.

Roger Dooley: Juliet, your new book is about busyness, how we all tend to be too busy and the impression I get is there’s the old expression, “Nature abhors a vacuum,” and it seems like in business any available time is something that nature abhors as well because things will immediately crammed in there to fill it, either of our own creation or not. Why is this such a huge problem and how can we begin to deal with that?

Juliet Funt: So in larger corporations where the busyness problem is the worst, we know that the version of what you said is business crap abhors a vacuum. So all the meetings and emails and decks and

reports and paperwork that people tend to be saddled with give them a sense that that level of activity is the same as being productive, and that confusion between activity and productivity is really at the heart of the problem you’re describing.

Another main component is the pervasive and passionate denial, that corporations and leaders are in about the cost of this waste. Because if they really looked at all those low-value tasks and quantified them according to salary value, which we do all the time with our clients, they would see spectacular numbers. We see a million dollars of annual waste for every 50 people in an organization, typically. So that’s like if you had 50 people and you said to 12 of them, “You guys can just eat Doritos and play video games all day long.” That’s the level of return on investment from those people that you’re getting, but we’re used to it. And so we keep ignoring it and we keep tolerating it. And we think that it’s just the way that work has to be.

Roger Dooley: Juliet, the problem about isn’t just these sort of extraneous activities that aren’t all that productive. I mean, because we could try and eliminate those. We could determine which activities aren’t leading to any better outcomes and say we’re going to stop doing those, we’re going to spend all that time on productive work. But I think you would make the point that we simply can’t be productive continuously if we are trying to be productive continuously even if it’s not on wasteful tasks, we’re still going to end up not being as creative or fulfilled as we could be, right?

Juliet Funt: Well, the foundational metaphor of the book and one that we should explore first is if you imagine if you built a fire, you’d want to get all the right ingredients. You’d want to get the little dry pine needles, newspaper, maybe that industrial white fire starter, and then the right kind of wood. But if you put it all together and you forgot one critical ingredient, it would never ignite and that ingredient is space. It’s the in-between oxygenating passages where the

fire has room to ignite and that is precisely what we don’t have at work. We don’t have a minute to think. We don’t have a minute to breathe. We don’t have a minute to reboot our exhausted bodies and without that space, everything we do is reduced in its impact.

So, you’re describing being productive all day long. I would still push back to say you’re probably still fluidly going back and forth between the definition of what is active and what is productive. Because if I put you in a bunch of Executives in a conference room for 8 hours and you sat quietly for eight hours and just did this. And then at the end of that 8 hours, you had a game-changing breakthrough idea that changed the nature of your business. You would call that a very productive day, but it wouldn’t be an active day. It’s just that we keep conflating the two.

Roger Dooley: I think it’s pretty hard to stay in that sort of continuous flow state where — I know you’ve written a book and probably there were times when you sat down and for 2 or 3 hours, just the words came out the way you wanted them to, and at least, I hope that happens.

Juliet Funt: On a good day.

Roger Dooley: It occasionally happens, in the hours of times it’s a bit more of a struggle. We do need that empty space in there. And of course, the challenge, I guess is to keep that from filling up with stuff because if I block out on my calendar, okay, I have this hour in the middle of the day or at the end of the day saying they’re not going to schedule. I’m still going to be drawn to — Well, gee, okay, I don’t have a call or specific activity so I’ll check LinkedIn or Twitter and see what’s going on or I’ll do something else and trying to actually create that white space and keep it open to me, seems to be a challenge. In fact, it seems like there’s a lot of social pressure, too. I mean, you read Gary Vee’s book Hustle and there’s this tremendous emphasis on a sort of a hustle culture that if you’re not going forward a hundred miles an hour, then you’re a loser.

Juliet Funt: Yes. Yeah, I think if Gary Vee and I stood in the same place we have both immediately, just self-destruct. Some sort of matter-antimatter. There are layers of accessing what you called the White space and that is the definition we use as well, we should talk about that a little bit. This space that we’ve been describing, the formal term we use is White space and we call it white because the name came from looking at spaces on a paper calendar back in the days of coaching Executives who had paper and realizing that when there were white squares an interesting thing happened, that that day held more promise and potential and creativity because there was fluidity in the day.

Now, the layers to access it are not just — There are layers. So first, we have to understand that we don’t have it. And then we have to really, really wrestle next with why we don’t give ourselves permission for it and that permission slice is non-negotiable as if something we have to pass through. In fact, when we were editing the book, I notice that we use the word permission 31 times in a normal-length manuscript. I sat with the editors saying, do we need to do something about this? And she said, “No, this is — We need 50 more permissions in this book,” because we just feel uncomfortable. As soon as the action stops, we’re flooded with thoughts, like I’m doing nothing. I’m slacking off. We have poor definitions in our own minds about the value of space. So all of that really needs to be wrestled with before we strategically move to what is the method by which we add this into our daily calendar.

And when we get there, I want to just say that the spaces might be a little shorter than your starting with. Most people are not going to take an hour of whitespace if I can teach them to take 5 seconds, 10 seconds, 20 seconds, a minute, they’re on their way to a different kind of life.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Well, explain how that process would work, Juliet. I mean, we’ve got somebody who sees themselves caught in this trap of continuously busy, not necessarily continuously productive. Where do they begin with creating white space in their schedule? I guess there are two ways of looking at this, is one from a person who is part of a much larger team, in a large company who may not have total control over their schedule, over their workday. Hopefully, they have some agency and then others like Executives who can set their own time. And also may be responsible for setting the timing of others.

Juliet Funt: So let’s take each population one at a time that you just rattled off there. So, starting with the executives that you ended with, we are in a time in professional history right now, where all of the work is being redesigned. All the car parts are out on the driveway and the gunk is being cleaned and we’re looking at them before we put them back together in hybrid designs, in post-pandemic designs. So, for leaders, this is maybe the most critical time ever to take a minute to think. And make sure that you’re being purposeful and strategic about the next work that you’re creating.

We almost have a blank slate to write on right now. It’s a very exciting times. But if leaders are not careful, they will get wrapped up in the busywork of re-entry. And all, they’ll be doing is logistics, logistics, logistics. They’ll be over-focused on where people sit and where people work and hybrid design, and they won’t take a minute to be strategic about the type of work environment that they like to create. So that’s a very important call to action. For people who are on teams, that permission aspect is more accessible when you talk about this together. So in order to start accessing White Space, one of the greatest things that teams can do is sit down together and talk about the space deficit and the costs of it. What does it feel like? Are we exhausted? Are we creatively running dry? Do we have no idea why we do the things we do anymore and could a little space help that? Once you start enlisting each other in this conversation, you feel bold or you feel empowered that space is something that you deserve and can actually take.

And then for the individual entrepreneur, retiree, we have in the book, there’s from sheep farmers to retirees who feel that they are too busy, family, doctors, and little mountain towns. We all suffer from it. The tool that I like to start people with is called The Wedge. Now, the wedge is a small portion of space that you insert in between two activities to open them up and uncompress them. And this is something that you can work in the most space unfriendly corporation in the world and you’ll still be able to use this tool personally. So between getting an email and responding or between a meeting and a meeting or between hearing something that is an affront to you, that makes you feel defensive and giving your response, between a thought and giving a question to somebody else. These are all little moments where we could just open up a little bit of space, one second, five seconds, ten seconds, a minute, and there starts to be a little bit of that oxygen in the day.

Roger Dooley: So how does the individual trigger themselves to do that? In other words, I say okay, well I’m going to be sure that meetings are at least ten minutes apart.

Juliet Funt: Sure.

Roger Dooley: And those ten minutes open up and immediately my thought is, well, oh, gee, okay, maybe I’m going to go get a cup of coffee really fast and I’m going to check email. I’m going to do this and that and pretty soon it’s time for the next meeting. Any tricks for making that sort of an intentional part of the day’s activity?

Juliet Funt: Sure. So we call it Hall Time, what you’re describing, we model it after classic high school system where you used to have two bells. You remember you had a bell and the bell said, “You should stand up and go,” and then the other bell said, “You should arrive and sit,” And there was this beautiful Hall Time in between that allowed you to have some oxygen. So from a meeting’s point of view, you just brought up a wonderful point and one that couldn’t be more valuable now in this Zoom-aholic life that we’re living. Five to ten to fifteen minutes of Hall Time between meetings is a critical use of White Space.

In order to not have it infused with the busywork you just described, we have to respect the Space. We have to begin by understanding that the recuperative and reflective gifts of that space are undeniable. Science backs it up, example backs it up. I could tell you a story after story. Maybe I’ll share a couple of leaders who’ve used this thoughtful time to their advantage. So once we respect that space, we begin to give ourselves that permission. And in terms of queueing ourselves, we can either do it through an intellectual choice where we do something like calendar it in or we can do it through a visceral awareness of when our body is queuing us that we needed. It’s that fried frazzle-y feeling where we’re kind of trying to get ourselves to pay attention and often trying to force ourselves into caffeine, sugar, or some sort of digital stimulant. And those are actually the moments when we need to recognize the bell that space is calling and we need to stop and just pause.

Roger Dooley: So what does this pause look like? I’ve said that space between meetings or between activities, what do I do then? I mean, I think about a waterfall in a forest or what? How do I create the right mental space to achieve what you want me to?

Juliet Funt: Sure. So I said, I promised you a leadership story or two. So from the grandest level will begin to say that if you show me, someone who’s achieved a lot of things, they absolutely take space in their day as a given. They take it as their right. So Bill Gates used to go away for two weeks every year on these famous think weeks. And Phil Knight of Nike had a chair in his living room that was designated only for daydreaming. And so, on an executive level, we see these grand examples of the use of the pause. And we want to figure out how does that trickle down to us? We think of it in this way, the paws can be used in four directions. Now yours, when you are slightly parroting, they do, I think of a waterfall, we would call the recuperative use of the pause. This is when your brain and body are so tired, you just need a, hah. But the recuperative use of space is only one of four ways that we use it and it’s the default setting that people assume all white space is.

So we have to break that assumption that all white spaces are for recuperation. It’s actually for a lot of other things. It’s also for reflection. That can be in that meeting, how did I do? Did I really read that client right? What went well? What could have gone better? What did I miss? It can be a pre-meeting reflection. Now, you’re turning toward the upcoming meeting. What do I need to prepare for? Which version of me and my bringing? What do I want to start with? That’s a reflective activity that all occurs in those pauses.

Next to use the pause to reduce. Now, this is a very, very large topic but it’s basically stepping back from all that waste work that we talked about quantifying at the beginning of the podcast and understanding how do we make that smaller. It’s taking time to really examine where work does and does not have value. And then the fourth use is constructive. And this is the creative space where we’re hatching products, we’re concocting plans, we’re getting the next great idea for our client. That only occurs when there’s nothing else on the table. And so taking a creative pause allows our creativity to arrive the same way you get water to run downhill. You just get stuff out of the way. It’s no creative magic but we just have room to do it. So those four uses are very important to go through because we need to break the presumption that all white space is for rest. It’s really only one usage.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm. Speaking of the number four, Juliet, another number four that you have are the four thieves of time. And these are things that would normally be considered positives. Like this is what we should be focused on and you point out that, “Well, maybe there are two sides to this coin.”

Explain those.

Juliet Funt: Sure. So the pernicious busyness that we described in the beginning, we have to ask ourselves, where does this come from? And when we studied busyness, we found that there were four main drivers that fueled almost all professional overload, but there was a big irony and surprise in that discovery, which was they were good things. That they were good things that had run amok. So the thieves of time are Drive, Excellence, Information, and Activity. And you think, “Well, I wouldn’t work anywhere that didn’t have those things. I wouldn’t hire anybody that didn’t portray those passions, but when they overgrow, they begin to steal our resources.” So the analogy I always use is there’s a plant in California called Morning Glory. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen this Vine.

Roger Dooley: Vine, sure.

Juliet Funt: It’s a beautiful purple-y, fairytale-y vine and has these little tendrils and you think I want — You drive by it on somebody’s trellis and you go, “I’ve got to get that,” and you go to the garden center and you get four pots of it. You put it up in the first month, it’s beautiful. It’s all over the side of your house and then you start realizing it’s clogging the doggy door and it’s trapped your bike spokes and it’s invading the neighbor’s roses and you loved this thing, but you can’t kill it. It’s resistant to pesticides. So that is the thieves. Beautiful, vibrant, glorious, but with a tendency to run amok and take over. And when they do, they become their own risk.

So Drive turns into overdrive, Excellence becomes perfectionism, Information becomes information overload, and Activity just becomes a frenzy. And so then they are no longer our friends.

Roger Dooley: One of the amusing stories that you have is about a security guard. And this is one of the most unlikely stories that I’ve come across in a business book lately, but why don’t you tell that one.

Juliet Funt: John. It’s one of my favorites really. It’s a perfect example of what we call the Constructive Pause, this use of white space to be generative. This gentleman named John. He works in Fortune 200 insurance company. And he’s a security guard, but he happens to work in a company that very much prides itself on innovative patents. And what is fantastically interesting about this man is that he, sitting in front of his surveillance monitor year after year, after year, actually holds the record for the most patents in the company. More than anyone in the Innovation Department, more than anyone in new technology. And so I met him and I interviewed him and he was an enormous advocate of white space as a concept.

Now, it is the reason that he has all those patents because his job is 95% white space and 5% acting on what’s needed maybe. Maybe he’s a — Yes, he’s a very individually, impressive thinker, and he has a very unique, brilliant, creative mind. But I believe so much of it for him is just that his job by definition, has so much permission for space. That he’s in a waiting mode all day long and in that waiting time, his brain is free in a way that his executives aren’t free and what was really, really interesting is he was transferred twice into Innovation and out of security and both times he quit and returned to security because he felt that the tasks that he was being assigned actually prevented his creative process, in the Innovation Department.

Roger Dooley: Right. It was pretty amazing. I think one other thing that I’ve certainly heard expressed more than one company is it somebody like that is told, “Look, your job isn’t to think, it’s to watch the monitors or to any building safe. We don’t want you to be thinking about stuff that isn’t related to that,” and of course, if cut it would have lost out on a lot, had they taken that attitude. So giving people the permission to think outside their space is pretty important, too. But it was fascinating that having all that time available, that at least he was able to put it to better use than many, I’m sure. But still, it’s an incredible story.

Juliet Funt: You said permission to think. We also have to keep floating in these extra words when we were titling the book Permission To Think, we talked about it’s really, it could be A permission to A Minute to Think, A Minute to Breathe, A Minute to Recuperate. A Minute — There are many kinds of minutes that we need and I think that there’s just a visceral intelligence sitting in the world right now, with all these exhausted people burn out, just cresting, breaking through the tops of all the charts where we just feel, “Don’t we deserve to just take a minute? Can we just take a minute to step back from all of this and allow a little space?” I believe it’s instinctively, in people already right now, the need for that element and they just have to have it acknowledged from an intelligent source.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm. I think that’s an extreme example, but we also see it in different departments where somebody from manufacturing as a marketing idea, and it never gets any traction. It’s like that’s just saying your own swim lane. So a really fun story and I would have enjoyed chatting with that individual myself. I’m sure one of the phrases you use in the book, Juliet, is an unusual one, Hallucinated Urgency. What is Hallucinated Urgency?

Juliet Funt: It’s part of the reason that we’re also frantic. It’s the sense that everything is time-sensitive by default. And so there’s this kind of pen clicking, toe-tapping frenetic pace. If you could take away the human sadness of it, it’s almost comical. When you walk into a larger corporation, you see everyone running around like they had seven espressos that morning which they may have. And it gets powerfully, in the way of work. Because it confuses all of us in our pursuit of understanding what’s really important and what’s really time-sensitive. So one of the phases of white space work is to break that presumption, is to understand that you’ve been tricked by an external metronome to think that everything is time-sensitive, then you’ve ingested that internal pace and now there is no vague doing it to you anymore. It’s just the way that you’re moving and it’s a choice and it’s a choice that can be chosen otherwise.

So we want people to start becoming more aware of that frenetic quality and stepping back from it. So, in the book, what we do is we give them three different tiers of urgency. And when they get together as teams and they use these tiers, they operate much more effectively. So I can share the tiers if you want. I think will help a lot is things can be not time-sensitive. We know that, but we don’t acknowledge it often, that’s number one. Number two, things can be tactically time-sensitive. That means that when you have the speed to do this thing, it actually has a positive business result. And those are the ones for which we want a sense of urgency. But the third and tricky category is that things can be emotionally time-sensitive. And that’s where so much of the real-life activities fall. Curiosity, pressure, stress, anxiety is causing us to advance ideas, projects, and requests at a pace that has absolutely nothing to do with their tactical necessity.

So again, we focus so much on teams in this work to get together as your teams and be able to share that language and then take it out into the field to say, “Is this actually tactically time-sensitive? Or is there maybe an emotional reason that we feel that it is?” And for executives, especially important, nervous, anxious Executives during all this difficult time that we’ve been through, our spastically sending out time-sensitive requests in every direction when they can stem it and realize how much of it is just curiosity and anxiety, they’re preventing their team from enormous amounts of unnecessary work.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm. And certainly, studies that show a missive from an executive gets treated with a lot of urgency, hey, this is the big boss, and the bigger the boss, the more urgent it is. And oftentimes, those might have been an offhand remark, just a question of curiosity or something. Not something that says, “Drop everything and find this out for me,” but so it is I guess. One area that I think impacts all of us is email. And it’s kind of a challenge because it’s one thing to say, “Well I’m only going to work on the important emails,” like if I look and say I’ve got a hundred emails in my inbox and probably 80%, we can just be deleted because they’re entirely unimportant. Maybe they’re only to about things that are actually important that are going to lead to some kind of a business result or could lead to a business result that’s important. But there are other things that are coming from people that I don’t want to be unhappy with me, or that might be important but I’m not really sure and all these sorts of things in the middle and if I fail to deal with them, they just build up and until I become stressful in themselves.

So there’s a real sense that I need to deal with these things now. Get them out of my inbox and then I can settle down and do my important thinking work, but of course, that’s not always happened. Do you have any strategies for email?

Juliet Funt: Yes, sure. A lot, a whole chapter’s worth. But that important work, I just want to say that you alluded to the time that that’s going to happen is after dinner, when the kids are in bed, you do the second shift with the laptop. And that is the worst time for people to be doing high-value work. At the end of an exhausting day when they should be rebooting with family, loved ones, hobby, joy. So it’s a very, very important thing to conquer. All right. The big spectrum of email is very, very daunting to the kind of spaciousness that we want. Not only because it’s pernicious, but because it’s also very addictive and we understand that the box that email comes in is a screen. And therefore, we are drawn to interact with it and they’re finding out so many fascinating things about our magnetism toward the screen itself, which I think is very important to talk about. If the email came in an auditory file that we listen to, we wouldn’t be as drawn to it as we are.

So once we acknowledge that factor then we have to understand the next level, which is that we, as teams are polluting each other’s inboxes without really thinking about it. We’re cc’ing and FYI’ng ourselves into a state of tolerated misery every day and we don’t have a lot of control about what comes in and what goes out. So I can go through just a couple of things that might make that easier for you. The CC demon is a very funny one to deal with because almost every professional at this point has been taught over and over and over and over to stop CC’ing people and yet, they can’t. And that from a psychological perspective of being told so many times to be cautious in that area and yet, to see that there is no caution, I find that just fascinating on its own.

There’s a lot of proving. There’s a lot of showing off of work. There’s a lot of fear-based undercurrents of making sure that people have visibility, all these motives that twist into our actions before we actually populate a CC field. But one of the best lines of demarcation that people can draw is between who has an action and who is an observer. I think of it like those hospital waiting rooms, where you’ve got a surgery going on and then there’s that glass-walled room above the surgery where everybody’s watching down. You don’t want a lot of people up in that room during your email thread. You want the people who have an action.

So one of the very simple things that we do with clients is we start them on a technique called WAIT. W-A-I-T is Whose Action Is This? And all you do is you fill in your CC’s as you normally would. Habitually, you probably going to put five, six, seven people in there before you even think about it. And then you pause and you bring in that moment of space and you say, “Whose action is this?” And you’ll find those very few people that you’ve put into that field actually have a reason and action on the thread. You’ve just popped them up into that glass-walled observing room and ask them to watch. And so it’s one simple technique in the time that we have but it’s a very, very effective one to start with.

Roger Dooley: Great. We’re just about out of time, how can people find you and your ideas?

Juliet Funt: Oh, thank you. It’s generous. So they can come to julietfunt.com and we’ve actually prepared something that they can do there, that will be of value for them. They can take the busyness test, which is a quiz, they should take it with their whole team and then sit and discuss the results that will help them understand, for them as individuals where busyness is coming from and how to do something about it.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, I will be taking that busyness test. After we’re done here, we will link to there and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We will have audio, video, and text versions of this conversation.

Juliet Funt: Great.

Roger Dooley: Juliet, thanks for being on the show.

Juliet Funt: Thank you so much. It was fun.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.