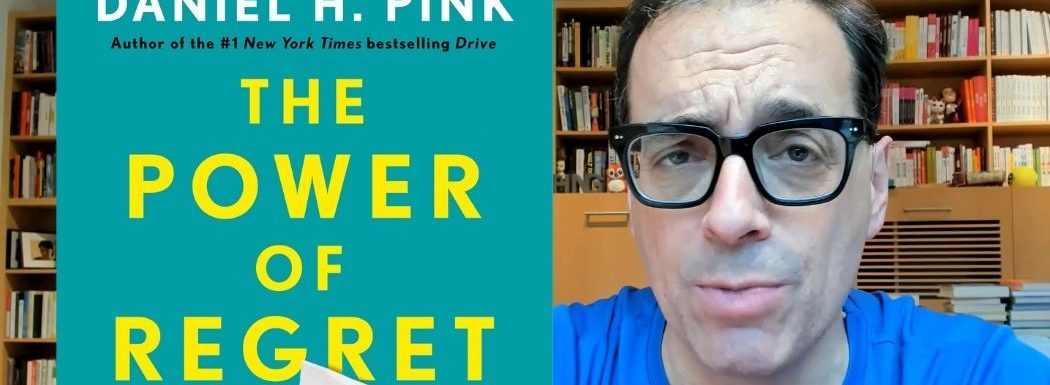

New York Times instant best-selling author Dan Pink always has promising research to unfold. For his most recent book, The Power Of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, Dan conducted what’s considered America’s largest-ever survey for analyzing the human attitude of regret. He surveyed more than four thousand Americans from a multitude of age groups, gender, and race about their experiences of regret. He also uncovered a trove of stories of human longing, aspiration, and insight from an online survey of 17,000 people across 105 countries. Dan deduced the types, reasons, and effects of regret and discovered its enormous power in adding meaning to our lives.

New York Times instant best-selling author Dan Pink always has promising research to unfold. For his most recent book, The Power Of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, Dan conducted what’s considered America’s largest-ever survey for analyzing the human attitude of regret. He surveyed more than four thousand Americans from a multitude of age groups, gender, and race about their experiences of regret. He also uncovered a trove of stories of human longing, aspiration, and insight from an online survey of 17,000 people across 105 countries. Dan deduced the types, reasons, and effects of regret and discovered its enormous power in adding meaning to our lives.

Dan joins us for yet another insightful conversation on Brainfluence to share the lessons gleaned from his qualitative and quantitative research. He describes the broader reasons for regret and explains how our regrets can be grouped in four areas: Foundation, Boldness, Morals, and Connections. By default, humans work hard to minimize every regret, something Dan points out can be unnecessary.

Dan says your overall goal with regrets should be to recognize them and their underlying causes. Then, use them to help both yourself and others in the future. Resolution, not rumination, is the key to a fulfilled life.

Listen to the conversation for a deeper dive into Dan’s work on regret!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Key Highlights for Dan Pink & Regret

● [3:59] The four types of regret we could minimize:

Foundation regret – A regret about not doing the work.

Boldness regret – A regret of not taking the chance

Moral regret – A regret of not doing the ‘right’ thing

Connection regret – A regret of not doing enough for a relationship

● [06:48] Inaction regrets outnumber action regrets. We are most likely to regret not doing something than doing it and realizing it wasn’t worth the shot.

● [10:09] Connection regret is one of the most common regrets we face in our lives but are often easily repairable. The awkwardness or fear of not being well-received by the other keeps us from mending them.

● [11:39] It’s essential to deal with a negative emotion like regret intentionally and positively and not ruminate over it.

● [15:30] A good way to utilize our regrets is while setting our new year resolutions. Take inventory of your life the previous year, assess your regrets, and find ways to keep away from those in the new year.

● [19:43] Moral regrets are tricky because what we think of as moral isn’t always the same for another person. As John Haidt explains in his book, The Righteous Mind, people’s notion of morality is wider than we think.

● [22:42] Dan’s Regret Optimization Framework explains why minimizing every regret is unnecessary; it would only cause us misery. Our intention should be to minimize regrets in the four categories of Foundation, Boldness, Morals, and Connections alone.

Dan Pink Regret Quotes

“These four regrets operate as a photographic negative of the good life. That is, if we understand what people regret the most, we also understand what they value the most. And so, this negative emotion of regret gives us a sense of what makes life worth living.”

“The pathway to New Year’s resolutions is to think about our old years’ regrets.”

“Feeling is for thinking and thinking is for doing. So, when we have negative feelings, we have to think about them, we have to confront them because they’re telling us something.”

“People who try to maximize every decision are miserable.”

'People who try to maximize every decision are miserable,' says @DanielPink while discussing THE POWER OF REGRET Share on X

About Dan Pink

With millions of copies of his #1 New York Times bestselling big-idea books sold, a renowned TED talk that has been viewed more than thirty-eight million times, lectures around the world, a popular MasterClass, and the acclaim of everyone from Oprah to Malcolm Gladwell, Daniel H. Pink has changed the way we live by changing how we think. With his extensive scientific research and practical takeaways, his books have transformed the professional and personal lives of his readers. In his newest book, Pink moves from big ideas to big emotions by exploring the transforming power of our most misunderstood yet potentially most valuable emotion: regret. Everyone has regrets. They’re a universal and healthy part of being human. But they often have an underserved bad reputation. In THE POWER OF REGRET: How Looking Back Moves Us Forward Pink helps us understand how regret works, how it can help us make smarter decisions, perform better at work and school, and most important bring greater meaning to our lives.

Dan Pink Resources

Website: https://www.danpink.com/

Book: Amazon

Twitter: @danielpink

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/danielhpink

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/danielpink/

Previous Episode: Psychology Goes Prime Time with Dan Pink

Share the Love:

If you like Brainfluence…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Dan Pink/Regret Transcript:

Intro: 00:00

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley shares powerful but practical ideas from world-class experts, and sometimes a few of his own. To learn more about Roger’s books, Brainfluence and Friction, and to find links to his latest articles and videos, the best place to start is rogerdooley.com. Roger’s keynotes will keep your audience entertained and engaged. At the same time, he will change the way they think about customer and employee experience. To check availability for an in-person or virtual keynote or workshop, visit RogerDooley.com

Roger Dooley: 00:37

Welcome to Brainfluence, I’m Roger Dooley. Today’s guest has taught us how to sell, how to motivate, how to use timing. Those answers should be enough to identify him as Best Selling Author Dan Pink. He’s been on the show before and I have been lucky enough to enjoy His company in person. Yes, he’s as smart and funny as you might expect. Every book Dan writes is a deep well-researched dive into a new topic. His latest title is The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward. I have to admit that regret wasn’t my shortlist of guesses for a new Dan Pink book, so I’m eager to learn why he chose that topic. And spoiler alert, the topic may sound like a downer, but it’s not. There are some surprising and practical takeaways in the book, and we’ll get to as many of those as we can. Welcome to the show, Dan.

Dan Pink: 01:18

Hey, Roger, it’s good to be back.

Roger Dooley: 01:19

Dan, how did you start on the topic of regret? Like I just alluded to, it’s not the most obvious thing to write about. It’s something people don’t even think about that much. Was that part of the key to it?

Dan Pink: 01:32

That was some of it. A lot of the stuff that I worked on started at a personal level, just wondering things about myself. And a few years ago, I was at my elder daughter’s college graduation, and it’s one of those moments, those milestones in life where you’re just wondering where time when, and why time moves so quickly? Inevitably, being in a college setting, I thought back about my own college experience, I started thinking about my own regrets there and began talking to people about that, and realized that even though our instinct is that people really recoil from regrets, I found that people instead leaned in when that topic came up. And I found it really intriguing from my own self. I would not have written this book in my 30s, but in my 50s, it felt sort of inevitable.

Roger Dooley: 02:14

I guess we’ve all had a chance to accumulate a few more elements of regret over the years. So, you actually did some of your own original research for this book, which is kind of unusual I think for a nonfiction book author who’s not an academic and has an army of grad students to do the research. Explain what you did?

Dan Pink: 02:32

Well, I did two different things. One of them is a piece of quantitative research. The other was a piece of qualitative research. And this kind of research is much easier to do these days than it was even 10 years, certainly 20 years ago. So, the quantitative piece of research is that I put together working with a data analytics company, the largest survey of American attitudes about regret ever conducted. So, we looked at a sample of about 4,489 Americans, representing what this country looks like by age, gender and race, and all that, and ask them a whole bunch of questions about what they regret, how they process regret, how often they experienced regret. And so, we get some good insights there. And then, perhaps even more valuable, I did something called the World Regret Survey, where I just put up a website that has so far collected regrets from about 17,000 people in 105 countries. It’s an incredible trove of stories, and human longing and aspiration. And together those two things gave me some insights into what we regret, why regret is much, much more effective and beneficial than we think. And combined with some of the social science on regret, what I’m hoping is that we can rethink our relationship with regret because it’s not only our most misunderstood emotion, but it’s also our most transformative emotion.

Roger Dooley: 03:46

You identify in the book four key types of regret, and I would not have thought we could break them down into major categories like that. Can you briefly summarize what those are? And we can see how many folks in our audience can identify with one or more of those.

Dan Pink: 03:59

You see, this is also a surprise. So, traditionally, academics have looked at when they’ve asked what people regret… both academics and public opinion pollsters have when they tried to determine what people regret, they look at the domains of people’s lives; so, this is a career regret, this is an education regret, this is a romance regret, this is a family regret. And what I found is that those categories weren’t that revealing. Let me give you an example about that. So, again, among people who went to college, huge numbers of people regret not studying abroad. “I wish I had taken the chance and studied abroad; I didn’t do that.” Huge numbers of people. That’s an education regret. Huge numbers of people around the world, Roger, it’s incredible, who regret not asking somebody out on a date. There was somebody they really liked, they wanted to ask that person out, they didn’t, and they’ve regretted it ever since. That’s a romance regret. And I’ve got huge numbers of people who regret sticking with a job and not starting a business. That’s career regret. So, we look at all those regrets, they’re in different domains, but to me, it’s the same regret. It’s a regret about boldness. It’s a regret where people say if only I’d taken the chance. And what I found is that beneath that surface domain, the surface domains of our life there are these as you say, four core regrets. One of them is foundation regrets, regrets about not doing the work. about not building a proper foundation, things like smoking and not working hard enough in school, and not saving enough money. There’s also boldness regrets, which I just talked about; if only I had taken that chance. There are a smallest group but very powerful of moral regrets where people look back at their lives, there was a juncture, they could do the right thing, or they could do the wrong thing, they did the wrong thing and they regretted it. Huge numbers of regrets, especially about bullying kids, and that lingers for decades, and marital infidelity, those kinds of things. And then finally, our connection regrets. And those are regrets where there was a relationship or should have been a relationship that came apart. Usually, it came apart slowly, and people regret that they didn’t do anything to bring that relationship back together. And to my mind, these four regrets operate as a photographic negative of the good life. That is if we understand what people regret the most, we also understand what they value the most. And so, this negative emotion of regret gives us a sense of what makes life worth living.

Roger Dooley: 06:13

How can you really tell when you talk about boldness regret? I think that probably many of us have those things that we wanted to do something and we couldn’t quite do it. But some of them seem so ephemeral, you have no idea how they would have worked out. You have a story in the book about the young man who met a young woman on a train or bus or something, and they have this fantastic conversation, then they never saw each other again, and he regretted not staying in touch or not having the ability to stay in touch. But good grief, what are the odds that that would have turned into a lifelong relationship? But it’s a lifelong regret.

Dan Pink: 06:48

But that’s what gnaws at us. And you’ve hit on a couple of important points, Roger. One of them is that if you look at people’s regrets, inaction regrets easily outnumber actual regrets. We’re much more likely to regret what we didn’t do rather than what we did do. And when it comes to that one category you’re talking about here, boldness, we don’t know how it’s going to turn out, but I can give you a glimpse from the database of regrets that gives us an idea. I have plenty of people… I have some people who, let’s say starting a business, I have some people who started a business and it failed, and that was a regret of theirs. But not that many people. There are some. Meanwhile, for every one of those, I have 25 who regret not starting the business. And I think one of the things we see with boldness regrets is that we’re much more likely to regret not taking the chance than taking the chance and failing. And I think that teaches something about what we want out of our lives. I think all of us recognize that we’re not here forever and that it’s important to do something, to learn, to grow, to do something psychologically which can take us to have a psychologically rich life. And when we fail to act, it gnaws at us. And when we act but fail, that actually bothers us less.

Roger Dooley: 07:58

I think there’s probably some interesting research on outcomes too, not just the fact you won’t have that regret if you act boldly. There’s research from Steven Levitt, the Freakonomics guy, that shows that when people are having difficulty making a decision, like a career decision, for example, like changing a job, that in general… Well, he tested in by randomly doing a coin toss in essence, and the person did accept the outcome of that, they either moved or didn’t move. What he found was that the people who moved were actually much happier on average after the experiment. And the way that you can interpret that is that we tend to have this… oh, it’s probably a combination of status quo bias and endowment effect, makes the decision seem more difficult than it should be. When something is clearly better, but we’d be giving up these things that we have now, we don’t do it. So, I think you’ve got two reasons.

Dan Pink: 08:53

It’s complex behavior, particularly, we’re talking about that realm of boldness. I think the other core categories are, in some ways a little bit different. They’re the same in the sense that they’re core to the human condition. They’re different in the mechanisms that work there. So, if you look at something like connection regrets, huge numbers of them, and it doesn’t really so much matter what the relationship is, it could be parents and kids, it could be siblings, it could be friends, one of the things that stuck with me in doing this research, particularly collecting these regrets, and interviewing a few 100 people about them is the importance of friendship and people’s lives, and what it feels like when those friendships drift apart. And that’s usually how they come apart; they usually drift apart. And what happens is that we think about reaching out, but we don’t. And the reason we don’t reach out is that we feel it, it’s going to be awkward, and we feel like it’s not going to be well received on the other end. And we’re almost always wrong about that. It’s less awkward than we think. And it’s almost always well received. So that’s a cognitive error in our projection of what the world is going to be like in our ability to imagine what’s going to be an upside and what’s going to be a downside in our decision-making. And there are relatively few cases where people reach out and they regret reaching out. And there are ginormous numbers of cases where people did not reach out and it stays with them the rest of their life.

Roger Dooley: 10:09

Well, at least many of those connection regrets can be fixed. You can reestablish that connection unless the other person is deceased or impossible to read or something. But there are others that really can’t be fixed. And your initial category of regret is foundational regret. These are often early life decisions like not completing a degree, not saving money when you were in your 20s, and choosing some sort of a path that really now at this stage of life can easily be altered. In fact, I noticed that we regret, both education related to. You went to law school, which you kind of regret, although I suspect that still served you well in many ways. And my similar regret is following the advice of my advisor and sticking with chemical engineering instead of going into computer engineering back in the early days when he assured me that, gee, that might be a fad, there’s always a need for chemical engineers.

Dan Pink: 11:06

Yeah, computers are just a fad. Here’s the thing, chemicals aren’t going anywhere either.

Roger Dooley: 11:11

Right. But when I look back, I ended up in the computer and digital space anyway. But I probably could have shortened that path by a couple of decades had I not done that. But at the same time, these are things that you can’t really fix. Well, we all have those kinds of issues, so how do we deal with those? How do we look at that and avoid regretting? I certainly don’t ruminate about this. It is what it is, and it’s turned out really well.

Dan Pink: 11:39

You mentioned that word, rumination, which is important. It’s important the way that we deal with any negative emotion, including a negative emotion like regret is really important. And I think that in many cases, we’ve gotten it wrong. And one extreme is this absurd philosophy of no regrets. “Oh, I don’t have any regrets.” All right, that’s a really bad idea. And what the research tells us is that everybody has regrets. The only people who don’t have regrets are five-year-olds whose brains haven’t matured, people with neurodegenerative disorders and brain lesions, and then sociopaths. The rest of us, not having regrets is the sign of either an immature mind or a grave disorder. So, we all have regrets. The question is, what do we do with them? One thing that we can do is we can say, as many people do, “Oh, it doesn’t matter. I’m going to ignore it. I’m going to overlook it. I’m going to deny it.” That’s a really bad idea. That leads to delusion. Now, what’s even worse idea is exactly what you said, Roger, which is ruminating over them, wallowing them, basically saying “Oh, my” and sort of getting trapped in them. What we need to do is we need to recognize that negative feelings are signals for thinking. That’s the key right here. Negative feelings aren’t to be tossed aside, negative feelings aren’t to be taken just as feelings, as things to bathe in. They’re signals. And when we get a signal like regret, it’s telling us something. And what we have to do is extract a lesson from it to go forward. Now, in some cases, let’s say saving money, it’s hard to repair. If you haven’t saved money into your 40s, you’ve got a problem. There’s an old Chinese almost cliche adage; the best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the second-best time is today. So, what you can do is you can start saving now. The other thing that happens a lot Roger as people age is that their regrets become tools and lessons they give to other people. So, I made a mistake, I have regrets about this, I don’t want you to have regrets about this therefore here’s the lesson I’m conveying to you. So, the overall goal with our regrets is to disclose them, to treat ourselves with compassion about having them because they’re part of the human experience, and then to extract a lesson that we can go forward. And when we do that. Regret has a huge array of benefits. There’s a pile of research on this. It makes us better negotiators. It improves CEO performance. There’s some really interesting research on how it can help our careers. It can deepen our sense of meaning. But it goes back to what you were saying before, it’s how we respond to these things. Don’t ignore, don’t wallow, confront, use it as a tool for thinking.

Roger Dooley: 14:15

I love the story about the fellow who had the no regrets tattoo, who ultimately regretted the tattoo and had to have it removed at a great expense.

Dan Pink: 14:27

What was it, like six or seven times more, maybe 10 times more expensive than having it in the first place? But that’s one thing that we can do. Now, there are certain kinds of regrets, certain kinds of action regrets, we can undo. We can actually compensate, we can repair, we can make amends. So, if you’ve been unkind to someone, you can always apologize. If you can’t reverse the unkindness, but you can apologize, you can make restitution, you can make amends. There are other things that you can do with certain kinds, especially action regrets, is that you can look for the silver lining in that. And that is actually psychologically helpful in many cases. I’ll give you the best example of this from the database. Huge numbers of people., 99% of them are women who say, “Oh, I really regret marrying that idiot, but at least I have these three great kids.” So, you at least… if you find a silver lining in that. That doesn’t help us improve in the future, but it helps us feel better in the present. And that can very useful as well.

Roger Dooley: 15:24

As we’re recording this Dan, we’re approaching the New Year, and you’ve got a particular strategy for new year resolutions. Explain that?

Dan Pink: 15:30

Well, I think that the pathway to New Year’s resolutions is to think about our old years’ regrets. And so, at the end of the year, or any time period, think about… to me, like think about the three things that you most regret. And when I came to the end of this year, one of my biggest regrets was connection regrets, which is that I have plenty of people in my life who have sort of drifted apart from, friends, mostly, and I just haven’t reached out. And so, I think… God, I really regret not staying in touch, I really regret not reaching out. And that positive side of that can become the basis for New Year’s resolution. So, that’s how I’m thinking about it. I look at my 2021 regrets, top of the line is connection regrets. And I say, okay, you know, what I have to reach out. I’ve also just sort of been bedeviled a little bit the last 10 or 15 years… is that I feel like I haven’t been bold enough in what I’ve been doing in my life. And that’s something that’s been really sticking with me for a while, and it’s telling me something, I can say, “Ah, it that doesn’t matter. I feel like I’m not being bold enough. Who cares? It’s a feeling. Feelings don’t matter.” Or I can say, “Oh, my God, I’m a terrible person. Oh, let me bathe in how terrible I feel about myself. Let me relish the negative emotion.” That’s a bad idea too. What I should do is say, “God, Dan, you know what? You have been feeling this sort of unease about not being bold for a while. The world is telling you something young man. What are you going to do with it?” And they’re all a whole variety of techniques to help us make better decisions for ourselves, to take those regrets, extract a lesson from them, and then use them to chart a path forward.

Roger Dooley: 17:04

You want to share a boldness plan for the coming year, Dan?

Dan Pink: 17:07

I don’t have a plan, but it’s at the top of my list.

Roger Dooley: 17:10

Wait for that opportunity to present itself.

Dan Pink: 17:11

Well, maybe. Yes and no. There’s a mix. It’s not connected to regret, but there’s an interesting work about how people make transitions, [unintelligible][17:22] has done some of this work, and about how do people make transitions, particularly when they’re at the stage of their life where I am, where I have a decent amount of mileage on me so I can look back, but I also have, I hope, a decent amount of mileage ahead of me so I can look forward. And the way that people often find the path forward is not by my sitting down here in my office, where I’m talking to you from and coming up with a strategic plan for the next 10 years, but really by experimenting your way toward that kind of discovery. But the catalyst for that is often regret. And when we feel that, I can’t emphasize enough how much that negative emotions, particularly regret, which is our most common negative emotion, negative emotions are useful. They’re telling us something, they’re giving us information, they’re warning us, but we have to be open enough to accept it, and not batting it away, saying it doesn’t matter nor taking it so severely, that we’re debilitated. I have to say, like William James, the great [unintelligible][18:24] the founder of psychology and America, once implied in some writing, that thinking is for doing. The reason we think is so we can act, but what’s been unresolved is what are feelings for. And to me, feelings are for thinking. Feeling is for thinking and thinking is for doing. So, when we have negative feelings, we have to think about them, we have to confront them because they’re telling us something. It’s like getting an email or telegram or signal from the universe. And we have to actually reckon with it. And when we do, there’s a pile of evidence showing it is a powerful way to do better in our lives, to make better decisions to improve our performance, and to find greater sense of meaning.

Roger Dooley: 19:05

One area of the book, Dan, is mortal regret, and that it seems to be an increasingly secular society, globally at least. Certainly not there yet. But I think the point that you’re making…. you can maybe clarify that, but that moral regret tends to stem from violating rules that are sort of a basic human nature, what almost any person of any background whether they are an atheist or a Christian or Muslim would say, yeah, that’s a bad thing to do. And so, moral regret comes from that type of action rather than violating a particular moral precept of whatever a belief you ascribe to.

Dan Pink: 19:43

It’s a great point and a great question. Moral regrets are tricky because what human beings think of as moral is not always the same. So, there are some areas on which there is incredible consensus, whatever your religion is. We shouldn’t harm other people unjustifiably for instance. We have an ethic at some level to care for other people. We shouldn’t cheat other people. But there are other things that there isn’t a consensus. And one of the things that we have to understand, particularly, and if we look at this globally, particularly in the secular well educated West, is that people’s notion of morality is vaster than we think. John Haidt, who wrote an incredible book called The Righteous Mind, talks about in terms of tastebuds, that is sort of secular, liberal, westerner, well educated, basically too moral taste buds, but they don’t have taste buds for things like authority, should you read… I’ll give you a mundane example from everyday life. There are some people who feel very deeply that kids should never call adults by their first name, they should always refer to them as Mr. so and so or Miss so and so. And there are some people who think, well, that’s ridiculous, just call them by their name. But we have to understand those are two very different views of say, authority. They’re very different views of desecration. There are some people, that made a classic example in America is flag burning. There are some people whose immediate response to flag burning is saying, “You know what? I don’t like it, but it’s a free country, you should be able to burn a flag.” There are other people saying, “You know what? This is such a desecration. We can’t allow this.” And it’s not like one of those is right, and one of those is wrong. They’re just different moral codes. And what’s interesting about the moral regrets is that… I’ll give you an example, I have people in this database, who regret not serving in the military. Now, there are plenty of people who say, well, that’s okay. But I don’t think that offers enough respect for that particular moral code, saying you have a duty of service, you have to protect, and that I actually feel a sense of regret that I didn’t step up and do that. To make things even less controversial, I have a lot of women in the database, who regret having an abortion. And we have different views on abortion, but understandably, this country is very divided on abortion. And we have to recognize that for some people having an abortion was a huge regret of theirs. And so, moral regrets are the smallest category, but they’re very tricky. On some things, we have a consensus about, on other things we really don’t. Anyway, to me, it’s a very, very interesting point. When we think about something like bullying, atheist, person of faith, whatever your religion, we think that’s probably a bad idea. Swindling a business partner, probably a bad idea. But on other ones, we don’t have full consensus on, and we have to recognize that people with different moral codes have different moral regrets.

Roger Dooley: 22:34

One of the solutions that you offer in the book Dan, is a regret optimization framework. And I love that name. Explains what that is?

Dan Pink: 22:42

Okay. So, this is my modest attempt to debunk Jeff Bezos, who came up with something that he calls the regret minimization principle. So, there’s a reasonably well-known story where Bezos was working as a banker in New York, and he thinks about starting this internet company. It’s 1994, I’m going to sell books over this thing called the internet, and his boss says, “You’re crazy. You shouldn’t do this. Take some time before you leave.” And he takes a walk in Central Park as the story goes. And he says, “Well, you know what? I know that when I’m 80, I’m not going to regret taking this chance.” And so, his view, and that became this thing… it’s what we should do is we should work hard to minimize all of our regrets. And there is some truth to that, but it needs a little bit of nuance, and it’s this; we cannot minimize every regret. If you say what car should I buy? I’m going to buy a car that minimizes my regret. What shirt should I wear today? I’m going to wear a shirt that… You’re going to go crazy. And so, there’s some really interesting research that shows that people who try to maximize every decision are miserable. And that there’s room for what’s called, and you know this Roger, some of your listeners might too but for those who don’t, there’s something called satisficing, which is just choosing a good enough option. And it turns out that people who satisfice are often pretty darn happy, and people who maximize often or not. And so, my view is what we should do when we anticipate our regrets is that we shouldn’t worry about our regrets in most realms of life, but we should maximize when it comes to these four things, that we should try to do everything we can to reduce our regrets about building a foundation, reduce our regrets about acting, boldly reduce our regrets about being mortal, and reduce our regrets about connections. We should make sure that we go crazy in a sense of reducing regrets in those areas and everything else, don’t worry about it. Make a decision, move on, you’ll be fine. And so, instead of minimizing all of our regrets, what we should be doing is optimizing the ones that are most important.

Roger Dooley: 24:33

Well, Dan, one of my regrets actually relates to satisficing. Herb Simon, he was actually still teaching at Carnegie Mellon when I was an engineer there and failed to go into computer science and psychology, so that amplifies regret a little bit. But chances are he would have had nothing to do with me as an undergrad student anyway.

Dan Pink: 24:52

You never know. He’s a Nobel Prize winner but he was one of the… they’re rare today as you know, he was a total Polymath. He was an economist, but he also did some early computer science. He was interested in psychology before most economists were interested in psychology. Again, this is not about regret, but I think one of the things that you see is that people who end up really contributing, often have some breadth to them. They are interested in a lot of different things and can see connections that people who are siloed in only one area can’t see.

Roger Dooley: 25:26

that’s probably a pretty good place to wrap up Dan. How can people find you and your ideas online?

Dan Pink: 25:31

Well, you can go to my website, which is www.danpink.com. I’ve got a newsletter. I’ve got all kinds of free resources. Anything that you will want is there.

Roger Dooley: 25:43

We will link there and to any other resources we spoke about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast Dan, it’s been great having you on the show and great reconnecting with you.

Dan Pink: 25:54

Thanks for having me back. I enjoyed the conversation, Roger.

Outro: 25:57

Thank you for tuning into Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s books, articles, videos, and resources, the best starting point is rogerdooley.com. To check availability for a game-changing keynote or workshop, in person or virtual visit rogerdooley.com