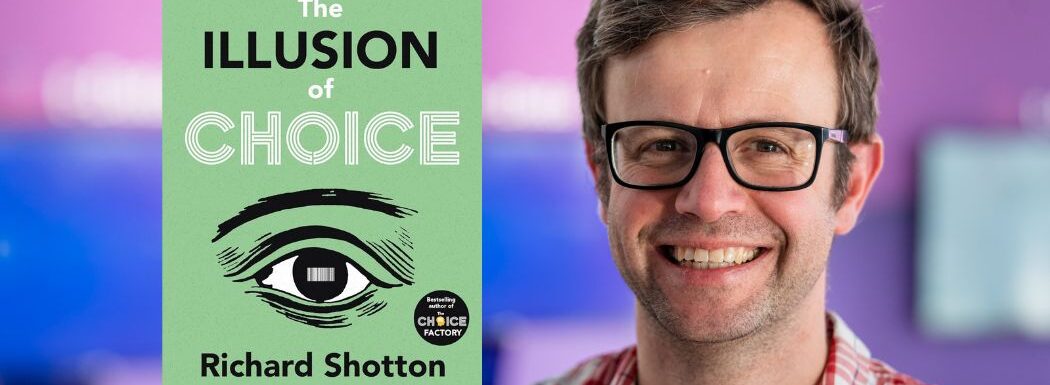

In this episode of Brainfluence, host Roger Dooley welcomes back Richard Shotton, a marketing expert with 23 years of experience working with major brands like Google and Mondelez. Shotton specializes in applying behavioral science to marketing and is the author of two books, including his latest, The Illusion of Choice: 16.5 Psychological Biases That Influence What We Buy.

In this episode of Brainfluence, host Roger Dooley welcomes back Richard Shotton, a marketing expert with 23 years of experience working with major brands like Google and Mondelez. Shotton specializes in applying behavioral science to marketing and is the author of two books, including his latest, The Illusion of Choice: 16.5 Psychological Biases That Influence What We Buy.

Listeners will learn about the reliability of behavioral science findings in marketing, the power of precise numbers in advertising, and how to use psychological principles like the “generation effect” to make marketing messages more memorable. Shotton also discusses the importance of reducing friction in customer experiences while explaining when a little friction can actually enhance perceptions of quality. Throughout the conversation, he provides practical examples and insights that marketers can apply to improve their strategies and better understand consumer behavior.

Listen or Watch

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Richard Shotton – Key Moments

Here is a list of key moments from the transcript with timestamps and a brief description:

[00:00] Introduction and guest background[00:54] Reliability of behavioral science in marketing

[03:39] The importance of replication in marketing studies

[05:39] The psychology behind “16.5” in the book subtitle

[08:01] Precise numbers in marketing and pricing

[12:44] The “intention to action gap” and creating habits

[16:14] Making it easy: Helping and hindering forces

[20:38] Why friction still exists in customer experiences

[22:40] The Ikea effect: When friction can be good

[26:19] The cork effect in wine tasting

[28:26] The generation effect in marketing

[32:28] Where to find Richard Shotton online

Richard Shotton Quotes

The Complexity of Marketing: “Even if a finding is genuine, as a marketer, you want to test to find out whether the insight works for you and your situation in particular.”

— Richard Shotton [00:06:58 → 00:07:09]

The Psychology of Behavior Change: “If you boost motivation, that’s all very well and good, but it’s often a necessary but not sufficient condition for behavior change.”

— Richard Shotton [00:14:01 → 00:14:09]

The Power of Small Changes: “Identify even the tiniest, most trivial bits of friction, stuff that feels like it’s so inconsequentially wouldn’t have any effect at all, and then put more effort into resolving that.”

— Richard Shotton [00:18:41 → 00:18:51]

The Reality of Decision Making: “We think people are logical, rational, deep, reflective thinkers, whereas in reality, and of course that can be the case, but an awful lot of decisions, most decisions are made speedily, in a reflexive way.”

— Richard Shotton [00:20:44 → 00:21:00]

The Ikea Effect Explained: “The more effort you put into a product, the higher quality you perceive it to be.”

— Richard Shotton [00:22:50 → 00:22:56]

Value of Revisiting Dubious Studies: “So I would say if you find these studies where the original was done in slightly dubious circumstances, don’t reject it entirely. Think of it as an unproven hypothesis, and maybe put it into your next research project.”

— Richard Shotton [00:30:06 → 00:30:20]

About Richard Shotton

Richard Shotton specializes in applying behavioral science to marketing. He has worked in marketing for 23 years and helps brands such as Google, Mondelez and BrewDog with their challenges. He is the author of The Choice Factory, a best-selling book available in 15 languages, which explains how behavioural science can solve business challenges. His latest book, The Illusion of Choice came out in March 2023. He’s the founder of Astroten, a behavioral science consultancy. In 2021 he became an associate of the Moller Institute, Churchill College, Cambridge University.

Richard Shotton Resources

Amazon: The Illusion of Choice: 16.5 Psychological Biases That Influence What We Buy

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/richard-shotton/

Website: Astroten

If you like Brainfluence…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Transcript:

Full Episode Transcript PDF: Click HERE

Roger Dooley [00:00:06]:

Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley. If you’ve read my book Brainfluence and liked it, you are going to love today’s guest. Richard Shotton specializes in applying behavioral science to marketing. He’s worked in marketing for 23 years with big brands like Google, Mondelez, Brewdog. On Richard’s last visit, we discussed his book The Choice Factory, a best selling book that is now available in 15 languages. Richard’s latest book is the Illusion of Choice, which turns academic findings into actionable advice for marketers. Welcome to the show, Richard.

Richard Shotton [00:00:35]:

Nice to see you again, Roger.

Roger Dooley [00:00:36]:

Yeah, Richard, I’d like to start by asking a question that actually your introduction of the book sort of sets up. You talk about how a lot of marketing advice is not based on science or based on anything that’s actually provable, and that, in contrast, we can rely on behavioral science findings because they’re peer reviewed. And over the last few years, we’ve seen, first of all, the replication crisis, where things like priming and some other work was called into question because other researchers who tried to replicate those findings couldn’t. And then more recently, it’s gotten even worse, where we’ve seen dishonesty research that apparently is dishonest, wherever some prominent researchers actually incorporated fraudulent data into their data sets. So this goes beyond the sort of little statistical manipulation or dropping an errant data point or two to make the findings look better. This really is fraud. Now, I think that probably at least a few of our listeners are wondering, okay, all of this work was peer reviewed. How do we know what to trust? Is any of this behavioral science stuff trustworthy? And so how would you answer that question?

Richard Shotton [00:01:54]:

Roger, I think it’s a great place to open, and I would recommend most people take a kind of nuanced point of view that it’s fine to have a skepticism, but if it becomes a cynicism, then you’re in a bit of trouble. And maybe it’s easier to think of the replication crisis if we think about another field, a more everyday field. So think about something like medicine. Now, medicine’s a fair analogy, because about as many papers replicate in oncology, the study of cancer, as they do in behavioural science and psychology. Now, when there are fraudulent researchers in medicine and there have been some very high profile cases, or simply there’s some statistical flukes, people I don’t think would react by saying, okay, well, there’s a rogue study. It’s been disproved. Well, because that rogue study was a lie. The whole field is hokum I mean, we can see when we think about medicine that that would be insane because one player has acted inappropriately.

Richard Shotton [00:03:03]:

You don’t reject all the findings. Now, I think you take that approach and apply it to behavioral science. If you find a paper has been created fraudulently, or probably more likely there was a accidental error in the methodology or just a statistical quirk in the data collection, the response should be proportionate. Strike that particular study from the database, don’t reference that again. But the findings that have been found to replicate again and again and again give those genuine credibility. And I think it’s a really important issue, and I try and address it in a chapter in my first book, the Choice Factory. And one of the points I make there is marketers are in a generally worse position because most of the theories and opinions and ideas we have in marketing haven’t ever, there’s been no attempt to replicate them. So we don’t know which ones are genuine, which ones are fraudulent.

Richard Shotton [00:04:07]:

At least with psychology and other scientific studies, people are going through the hard work of trying to retest ideas again so we can start sorting the wheat from the chaff. So two principles here. Firstly, make sure you are striking out studies and not applying them once they’ve been debunked. But secondly, within marketing, I think we could learn from a lot of these fields and start trying to replicate many of the findings that come from other sources.

Roger Dooley [00:04:39]:

I think that marketers have replicated, not necessarily in as scientific or academic a way as researchers, but many marketers constantly use tools like social proof or reciprocity or many of these tools have been around for decades, and in fact, we know they work in most cases. Now they’re not going to work in every case, but that’s okay. Social proof is going to work for many things, but not everything. But I think that those are reliable. And usually the more startling a finding is, and sort of counterintuitive, like, wow, that’s really unusual. And if there is no replication, then maybe that stuff should be called into question. I guess we probably both feel a little bit betrayed occasionally. I know that, for instance, Brian Wansink’s work at Cornell, I’ve quoted in brain fluence and really did some wonderful little studies on, particularly marketing of food that were so nice, so actionable.

Roger Dooley [00:05:39]:

And now it’s like, well, which one of those studies is, which of those studies are actually real? And many of them have not been replicated. So I’m just really not using those. Have you gotten pushback from clients about this topic in recent times. In other words, are people saying, well, yeah, all this behavioral science stuff is baloney?

Richard Shotton [00:06:00]:

I wouldn’t say it’s a common reaction, but there have been a few mentions recently, and it’s much better if someone states that directly rather than just thinking it and not expressing it, because if they state it directly, you can address it. So there have been a couple of comments and I think part of it is a reflection of behavioral science, certainly in the UK, becoming a mainstream topic of debate amongst marketers. So now, knowing that it’s not magic and it always works, I think to some degree shows a level of sophistication. I thought, Roger, two things that you said were really interesting in that point around social proof, for example, that people have known about these ideas for ages, but even for a finding like social proof, which is a genuine, robust finding, been shown in lots of different circumstances, you make the point, it doesn’t work in every single instance. So even if a finding is genuine, as a marketer, you want to test to find out whether the insight works for you and your situation in particular. So, for example, with social proof, there’s a couple of studies that might be of interest. The behavioural insights team in Britain, I think, back in 2011, ran a study looking at social proof to encourage tax repayment rates. And although they found it was very effective overall, they found that actually it backfired amongst the top 5% of debtors.

Richard Shotton [00:07:31]:

So the super rich genuinely didn’t believe that they were influenced by others. So mentioning what the average person did backfired amongst that group. And then I think it might be was MEC did a study where she showed that as people aged, it’s not that social proof wasn’t effective, it just became slightly less effective. So, absolutely. Even for genuine findings, I think you’re right about the importance of context, and the impact will vary from one context, one category to another.

Roger Dooley [00:08:01]:

Richard, the subtitle of your book is “16.5 Psychological Biases That Influence What We Buy.” The 16 and a half number is rather unusual for a book subtitle. I’m guessing there’s some psychology behind that.

Richard Shotton [00:08:14]:

Absolutely, absolutely. I thought if I’m going to write a book about behavioral science, I should at least apply some of the principles to the book itself. So I was drawing there on the work of brilliant psychology called Schindler, who’s at Rutgers University. He does a super simple study, recruits a group of people, shows them two versions of an ad. So both ads are for a deodorant. Same picture, same description. But one ad claims that it reduces perspiration by 50%. So a very round number.

Richard Shotton [00:08:47]:

The other half of people see an ad that says it reduces perspiration by 47 or 53%. So one group see 50%, one group see 47 or 53%. He then questions both groups as to the believability and accuracy of the claim, and he finds that the group that saw the precise number rate the accuracy at plus 10%, the credibility believability at plus 5%. So his argument is people begin to notice over time that communicators who don’t know what they’re talking about, speaking generalities, those who are certain of themselves and have making claims from knowledge, they tend to talk in precise numbers. Now, if you think about your own situation, you can see this acting out. If someone says to you, how old’s your brother? You say, 62, 49, 53, you know, you give an exact number. If someone says, how old’s the lady who lives five doors down from you on your street? You might say, okay, she’s in her fifties, she’s in her sixties. Now, if we know what we’re talking about, we tend to talk precisely.

Richard Shotton [00:09:57]:

If we don’t, we’re talking generalities. And over time, people begin to fuse those two things together. So I applied it into the subtitle of the book. But if you’re a marketer, you could easily apply this. Loads of marketers currently go out and talk about their popularity in very suspiciously rounded numbers, or they talk about the amount of time it takes to fill in a survey of five or ten minutes or two minutes. They pluck very round numbers out. The argument here would be much more precise. You haven’t got 10 million customers, you’ve got 10.3 million.

Richard Shotton [00:10:32]:

It’s not going to take five minutes, it’s going to take four and a half. The more precise you are, the more believable and accurate you’ll be perceived.

Roger Dooley [00:10:40]:

That works for prices as well. There’s research on that that shows that people found prices to be more accurate and believable when they were precise. This isn’t a dollar 500 television, it’s a $497 television or $503 television. I see some marketers using this quite a bit. If you look at typical social proof claims for, say, newsletters sometimes see we have 25,000 subscribers, or you might see we have 23,507 subscribers, which, again, it’s a slightly more believable number.

Richard Shotton [00:11:16]:

Yeah.

Roger Dooley [00:11:16]:

So, yeah, always good advice. Be precise. Makes a lot of sense.

Richard Shotton [00:11:21]:

I think, especially on your point about price. So there was a University of Florida study. I’m probably going to muck up the pronunciation. So apologies the academic self. I think it was Janiszewski who did the study, I think you’re referring to, and this was slightly abstract in that it was asking people what they might do. There’s an amazing study that’s come out from Uber, or at least Uber have commented on data that their behavioral science team have run. So they’ve shown that when people are shown a surge price, they are more likely to accept a 2.1 x surge price than the two x surge price. Now, I love that as a finding because it’s as robust as you can get in the.

Richard Shotton [00:12:04]:

No one knows they’re taking part in these experiments. There’s not an opportunity for them to fake their behavior. They’re just getting into an Uber without realizing they’re in an A B test. And so it’s a really, really strong finding, massive sample size. And then the second great bit about it is it’s a really rare finding because you can increase your price from, say, ten dollars to ten dollars, fifty cents. You can increase your price, get better margins and also increase your conversion. So that’s a lovely point, Roger. I think that’s definitely something people should be thinking about testing.

Richard Shotton [00:12:37]:

If you’ve got round prices, why not test making them precise and seeing if you can benefit from both great conversion and higher margin?

Roger Dooley [00:12:44]:

I think that echoes your earlier point too, Richard, about the importance of testing rather than just running with some kind of a finding from behavioral science, because so often behavioral science studies are conducted with a small group of subjects who might be undergraduate students in one institution and may or may not represent everybody on the planet, most likely not. But when you can run your own test across your customers at scale, that’s very good data to have, and you can use that then to plan your future actions. So, yeah, that’s great stuff! Richard, one of the kind of amusing studies that you cite in your article was done by Katie Milkman and involved a stuffed green alien. Can you mention that or describe that?

Richard Shotton [00:13:33]:

There’s some lovely work by Milkman, and I think the part where I’m talking about there is trying to create habits. The main focus of the section is a really important idea called the intention to action gap. So many martyrs try and change behavior by motivating people to want to change. And there’s an argument from psychologists by people like Susan Milne. Was it Sarah Milne, where she says, look, if you boost motivation, that’s all very well and good, but it’s often a necessary but not sufficient condition for behavior change. Alongside getting people to want to exercise or want to eat healthily or want to purchase your product, you need to make sure that there is a very clear cue or trigger that people associate with your product. And it’s when you combine those two things that you unlock the greatest effect. Many, many brands boost appeal very successfully, but they forget about the simpler part, which is associating their product consumption or their product purchase with a time, a place or a mood.

Richard Shotton [00:14:45]:

So the argument here would be, think about what kitkat do in the UK. They talk about have a break, have a kitkat. Actually, I think the line might be different in the US. Or snickers. You’re not you when you’re hungry. They’re being very clear about the moment that you should think about their products. And by being very clear about that time, place or mood, you effectively convert vague intention into concrete action. Now, what Milkman showed is if you’re going to create a trigger, this kind of cue or trigger moment, try and make it as distinctive as possible.

Richard Shotton [00:15:20]:

And if you do that, you’re going to have the best success.

Roger Dooley [00:15:24]:

And in her example, or in her study, to remind customers to use a coupon, I think they were told, when you see the fuzzy green alien, then use the coupon, and then they tested the coupon use with and without a little stuffed alien by the cash register. And in fact, when the stuffed alien was there, there was a higher conversion rate. And I think that can even apply to personal habits, too. If you’re trying to remember to do something, put something weird and out of place there as your cue, and then you’ll remember to do it. How many times have you said, okay, I’m going to do this first thing in the morning, and then, of course, you get to lunchtime and realize that you failed to do that thing. If you had your stuffed green alien by your computer monitor, you probably would remember to do that thing.

Richard Shotton [00:16:14]:

Absolutely. I think the people might be thinking, okay, well, stuffed green aliens, that’s a big jump to my huge business problem. But you can see some of the world’s most successful brands or categories applying this principle. My favorite example is champagne. Now, champagne is a multi billion pound industry, but really, is it any nicer than a merlot or a pinot noir? I don’t think you can explain the financial success just from the taste. Arguably, the success comes from the brilliant taste and the very clear trigger moment. Champagne goes together with celebrations, it goes together with New Year’s, it goes together with birthdays. Promotions.

Richard Shotton [00:16:56]:

It’s very clear the moment when you should use the product. My mum is basically teetotal. She doesn’t even like the taste of champagne. But New Year’s Eve, she’ll still bring a bottle out. That’s the power of a trigger moment. So, yes, I think you can apply it in small is like Milkman’s green alien study, but the underlying principle that can be applied on a massive scale for great profits for any business.

Roger Dooley [00:17:22]:

You’ve got a section in the book called making it easy that discusses friction, which, as you might guess, is one of my favorite topics, Richard. And one area that you get into that I don’t specifically talk about is the concept of helping and hindering. Can you explain that a little bit?

Richard Shotton [00:17:36]:

It’s a really nice analogy that I think Tim Harford, who’s an English economist, has. So he kind of draws on work by Kurt Lewin and Daniel Kahneman, but I think explains it really clearly. So he says, look, there’s two ways to change behavior. What you were referring to as helping force is, he says, this is motivation. You can push down on the accelerator, you can make people want your product. And the argument is marketers tend to focus on that part, motivating people to want to change. The other part of the equation, though, is you called hindering forces, which he calls in his car analogy the handbrake. That is, the small barriers that are getting in the way of people changing their behavior.

Richard Shotton [00:18:18]:

And the argument from people like Kahneman, Thaler, Tim Harford. It’s that we tend to underestimate the impact of those really small hindering forces, the small barriers that get in the way of change. And because we underestimate them, most people put too little money into resolving them. So the argument here would be, go through your customer, Jerdik. Identify even the tiniest, most trivial bits of friction, stuff that feels like it’s so inconsequentially wouldn’t have any effect at all, and then put more effort into resolving that. So an example might be Netflix. Now, if you wanted to motivate people to watch more tv, you would spend, as they do, billions of pounds on great tv shows. But if you wanted to focus on the hindering force, you might think about, well, what are the tiny little barriers stopping people watching that next program? And they also looked at that.

Richard Shotton [00:19:13]:

So it used to be with Netflix, you had to, at the end of your program, go and find the remote control. That’s a two second barrier. Now they’ve got rid of it. So the next program in the box set autoplays. You have to go and find your remote control if you don’t want to watch the next program. So by thinking of accelerating the handbrake hindering helping forces, if you look at those two angles, it gives you two different prompts to solve the challenge. And the watch out from behavioral science perspective is if your organization is anything like the norm, you’ll probably be putting too little attention on those hindering forces.

Roger Dooley [00:19:53]:

That ties into the work of BJ Fogg too, where he says basically getting somebody to act is an interplay between their motivation and what he calls ability, which is lack of difficulty. It has to be easy and same finding and same concept. Why do you think with so much both academic work and even commercial work in this topic, why do we still see so many customer processes that are more arduous than they need to be, websites that don’t work particularly well, where you’ve got to do too many clicks, too many keystrokes, or you reach point of confusion, and so on. Why is there still so much friction in the world?

Richard Shotton [00:20:38]:

I think because an awful lot of marketing is based on the wrong model of human behavior. We think people are logical, rational, deep, reflective thinkers, whereas in reality, and of course that can be the case, but an awful lot of decisions, most decisions are made speedily, in a reflexive way. So people probably think to themselves, well, I’ve made this amazing mortgage or trainer, surely someone will push through these tiny little barriers. It doesn’t really matter if we ask them to fill in a six point form because it’s only 10 seconds of effort, surely they should be motivated enough to push through to the other side. So I think we have that model, that untested model, often in our minds to represent the consumer. And because we have that model, it doesn’t seem worth the investment. And it can be quite expensive to rationalize a website or to make a customer journey easier, and therefore we can’t justify that cost. So the great thing about behavioral science is it replace existing models of human behavior, which are often based on speculation and introspection, with a more accurate model which is based on experiments and research.

Richard Shotton [00:22:03]:

So I think that could be a big reason.

Roger Dooley [00:22:06]:

One of my favorite areas of friction is packaging. Friction. People hate these horrible heat sealed plastic clamshell packages that you have to get your way into with sharp instruments and risk personal injury. And Amazon found that people not only liked their frustration free cardboard packaging better, but the products themselves had far fewer negative reviews when they were packaged that way. But you point out in the book that sometimes a little bit of extra friction in the packaging can be a good thing. What are a couple of examples of that?

Richard Shotton [00:22:40]:

I talk a bit about a Michael Norton study from 2012. I think the Ikea effect that people may well be aware of, and it’s essentially the idea that the more effort you put into a product, the higher quality you perceive it to be. So their example, recruit a load of people, bring half into a room with a preassembled Ikea box, get them to bid on the box, say how much they’re prepared to pay for it, to take it home. I think from memory, it’s like $0.40 or something like that. Next group, they’re brought into the room, same Ikea box, but this time it hasn’t been assembled. They get the participants to build the box, and then afterwards they ask them to bid on it and say how much they prepared to pay to take home with them. And I’m doing this from memory, but I think something like, say, $0.60 is the average bid. So it’s about a 50% variation.

Richard Shotton [00:23:33]:

The argument here is because people have put effort into it, they feel that that product is going to be higher quality. Now, you can apply this, I think, in areas like packaging. The effort that people put in, you don’t want to get interpreted as frustration. But if you put friction in at the right moment, then it can help bolster some of those quality perceptions. So you think about Apple, for example, when the iPhone arrives, it doesn’t arrive in a, you know, cardboard box that just pops open with a single flip. You have to just, you know, gently peel it out from that cardboard outer and there’s just enough pressure that whilst it’s not complex to do, it does take a little bit of effort. That’s a brilliant way of turning a bit of friction into a perception of quality. Now, sometimes as you begin talking about that experiment, people think, wow, wait a minute, 1 second you’re saying remove friction.

Richard Shotton [00:24:36]:

1 second you’re saying add friction. Now, I would explain that contradiction by saying which of those experiments is appropriate? Depends on the context and the challenge. If you want to change behavior, 99 times out of 100, remove friction. Removing a small barrier will have an unexpectedly large effect. So if it’s about changing behavior, if you think there is an intermediary step where you want to boost perceptions of quality, well, that’s where you might want to add friction at a very select moment or two, whether it’s the apple box or the cork in a wine bottle, be very careful about removing those types of friction where it sets up expectations about product quality.

Roger Dooley [00:25:26]:

I think in the cork example, Richard, I might push back a little on that one and suggest that there’s another effect that people. There’s lots of research that shows that people think wine tastes better when they’re told it’s expensive wine. And it seems like those findings are fairly robust, even down to the fMRI level of people finding wine more pleasurable when they think it’s a $50 wine instead of a five dollar wine. And I think you could possibly make the case that the cork effect isn’t so much from the effort that goes into opening, although that could well be. But also the fact that people associate screw tops with inexpensive wine, that like the cheapest wine in the supermarket, that you’re going to take on a picnic with you or something and won’t have an opener available. So I think that there could be that effect as well.

Richard Shotton [00:26:19]:

I agree. I think they probably effects that complement each other. So you’re absolutely right. Evidence suggests expense creates positive expectation, and then that positive expectation creates a positive experience. There’s some lovely studies by Abba Shiv on the wine front. Exactly the same wine served. Some people think it’s $5. We’ll get a much worse rating than the same wine served to people who think it costs dollar 45.

Richard Shotton [00:26:46]:

I think it’s of the order about. In fact, it’s a 70% improvement. So, absolutely. That finding, I think is contributing to much of it. But there’s in the book I talk about a lovely study by Charles Spence, where he tries to unpick the two, and he shows if people uncorked the wine themselves, there was a greater uplift in taste perceptions than if they just heard the wine being uncorked versus unscrewed. Now someone else is doing the effort. So from memory, I think the majority of the uplift is from those perceptions of price that come from a cork. But some of it was the amount of effort involved.

Richard Shotton [00:27:31]:

Now, let’s go back to our very first question, which you raised is around replication crisis and such things. We’re now down to a single study that tries to unpick the relative weight. I would have that as a interesting hypothesis, and if I had to bet on one side, I’d go with the split we’ve just been talking about. But absolutely, it’s a single study. So definitely to be treated with caution.

Roger Dooley [00:27:57]:

Maybe in a restaurant, the sommelier a should just deliver the bottle and the corkscrew to the table and let the customer open it. The wine might taste even better after that.

Richard Shotton [00:28:07]:

Bring them into the kitchen and let them cook themselves as well. This could be a.

Roger Dooley [00:28:11]:

There you go. You have the Ikea effect, right?

Richard Shotton [00:28:13]:

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Roger Dooley [00:28:15]:

Well, there are those places that do let the diners participate in preparation, so maybe there’s something to that. But I want one last question for you. Can you describe the generation effect?

Richard Shotton [00:28:26]:

Oh, yes. So a wonderful study, I think, was 1978, University of Toronto. Graf and Slimecker get a small group of students. We’ll come back to that point, and they basically give them lists. One group get a list that says fish, cat, dog. The other group get f blank, sh do c a blank. Both groups get the same time to look through the lists. The lists are then taken away, and then both groups are questioned as to how much they can recall.

Richard Shotton [00:29:04]:

And from memory, I think it’s a 15% higher level of recall amongst the group who had to generate the answers themselves. So if you saw c blank t, you had to do a little bit of work to come up with the answer being cat. It was that group that were more likely to recall the words. The argument being, putting that little bit of effort in, you know, this self generation, the answer makes the idea or the facts slightly stickier. Now, I mentioned the. That was a small sample size, and it was on students who aren’t exactly representative. And that sometimes occurs with, especially the 1960s, 1970s psychology experiments. So I reran that study on a much larger sample with a Mitra Harnett Liabanetz, and we did the same approach, but used brand names.

Richard Shotton [00:29:57]:

And we found that finding, when you do it on a nationally representative audience, on a much larger sample, is still robust today. So I would say if you find these studies where the original was done in slightly dubious circumstances, don’t reject it entirely. Think of it as an unproven hypothesis, and maybe put it into your next research project. The findings are all, sorry, the methodology is all there in the public domain. You can take that same methodology, maybe twist it to fit your category, but twist it so the bigger audience representative, and then you can see whether those findings still hope today. And there’s quite a few occasions, there’s about a dozen, maybe slightly more occasions where I’ve done that in the book to try and verify the experiments when I thought they weren’t quite up to standard.

Roger Dooley [00:30:46]:

How do marketers use the generation effect?

Richard Shotton [00:30:49]:

Some people do it very literally. There’s a very famous whiskey ad by JMB where they just ran a green page at Christmas and it said, dash ingle, dash bells. It was something like JMB makes the difference. So that would be a very literal use of the idea. But you can apply these principles a bit more laterally as well. If you think back to the classic economist campaigns, lines like, I don’t read the Economist, management trainee, age 42, I would say that’s a slightly broader, more creative, more lateral application of the generation effect. The economists don’t tell you you will be a failure unless you read our product, partly because just telling someone and not allowing them to be involved in creating the answer is not very memorable. And secondly, it’d feel a bit arrogant.

Richard Shotton [00:31:43]:

But by setting a small puzzle for people to solve themselves, you give people the burst of excitement that comes from success. It allows you to convey what could be seen as a slightly nasty idea. You won’t be a failure, you won’t be a success if you don’t read this. But then going back to the generation effect specifically because people have come up with the answer themselves, then it will be much, much stickier.

Roger Dooley [00:32:09]:

Reminds me of the old classic Absolut dvodka ads that did not show the product, but it showed various things, objects, whatever that suggested the shape of the bottle. And then people, of course, had to fill it in themselves. This is a probably a great place to wrap up. Richard, how can people find you and your ideas online?

Richard Shotton [00:32:28]:

Through bookstores, Amazon or whatever? Got two books, the choice faction, the illusion of choice. So that might be a good starting place. But also on Twitter at @rshotton, I tweet about behavioral science and marketing, or via LinkedIn, I do something very, very similar.

Roger Dooley [00:32:43]:

Great. Well, we will link to those places on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast and in the YouTube notes. Richard, thanks so much for being on the show. It’s been fun talking.

Richard Shotton [00:32:54]:

Fantastic. Thanks a lot, Roger.