In this episode, we’re exploring the sweet spot between marketing and psychology to uncover why people make decisions and reach the judgments that ultimately shape their lives. Listen in as Adam Alter shares how cognitive fluency can help or hinder persuasion, how the pandemic has forced a cultural shift over how we view screen time, and why word choice is an important consideration in brand names and marketing copy.

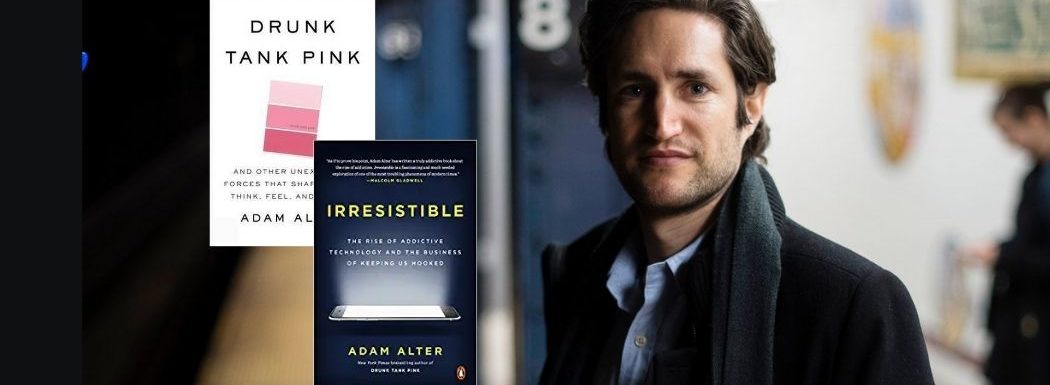

Adam Alter is a professor of marketing and the Stansky Teaching Excellence Faculty Fellow at New York University’s Stern School of Business, as well as an affiliated professor of social psychology in NYU’s psychology department. In 2020, he was voted Professor of the Year by the student body and faculty at NYU’s Stern School of Business. Also the New York Times bestselling author of two books, Adam has shared his ideas with thousands of people across dozens of audiences, including through his TED Talk, the Joe Rogan podcast, the World Economic Forum, and at dozens of companies and non-profits, including Google, Microsoft, and Amazon.

Learn how our environment shapes our decisions and judgments with @adamleealter, author or DRUNK TANK PINK. #digitaladdiction #psychology Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Watch:

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The story behind the name of Adam’s book.

- What cognitive fluency is and how you can use it to your persuasive advantage.

- The importance of word choice and language in persuasion.

- How the pandemic has forced a cultural shift when it comes to screen time.

- The impact of our environment on our decisions.

Key Resources for Adam Alter:

- Connect with Adam Alter: Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | LinkedIn

- Amazon: Drunk Tank Pink: And Other Unexpected Forces That Shape How We Think, Feel, and Behave

- Kindle: Drunk Tank Pink

- Audible: Drunk Tank Pink

- Amazon: Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked

- Kindle: Irresistible

- Audible: Irresistible

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome Brainfluence, I’m Roger Dooley.

Today’s guest is in the sweet spot for this show. The intersection of marketing and psychology. Adam alter is a professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business, and also of social psychology in NYU Psychology Department. In 2020, he was voted professor of the year by the student body and the faculty at NYU Stern School. And he’s the author of two New York Times bestselling books, Drunk Tank Pink, one of my all-time favorites, and Irresistible. His Ted Talk has been seen over a million times and was named one of the 10 best Ted Talks of 2017. Welcome to the show, Adam.

Adam Alter: Thanks very much for having me, Roger. I appreciate it.

Roger Dooley: So great to have you here. I’m reaching off here because I have both of your books here in my possession.

Adam Alter: Thank you.

Roger Dooley: I think Drunk Tank Pink was how I first got to know you or know of you, and it’s really one of my all time favorite books. First, I have to comment on your being professor of the year in 2020, was that pre-pandemic when it was live or was that the virtual, Adam?

Adam Alter: It was just pre-pandemic. Actually need the voting happened during the pandemic, but it was based on teaching that was done right up until March.

Roger Dooley: Okay.

Adam Alter: So, it was really tweaked 2019, but then as the voting happened in 2020.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Got it. Either way, that’s pretty impressive. And both the students and the faculty vote on that. How does that work?

Adam Alter: There are two separate awards. The students vote on one of them and the faculty vote on one of them. And I just happened on the same year to vote the same way this year.

Roger Dooley: Just happened is probably, honesty, Adam. Well, what’s the correlation between those two? Is there enough of a history to tell?

Adam Alter: There’s a pretty long history. I knew Nothing of the history until now. It’s voted on faculty across the whole of the business school, so they’re coming from lots of different departments. I don’t think a marketing faculty member had one for some time. So, when I ask people in marketing what the story was, a lot of people had no idea. But I think usually they diverged. So, this was unusual.

Roger Dooley: That’s great and congratulations on earning both of those.

Adam Alter: Thank you.

Roger Dooley: So, I would describe Drunk Tank Pink as somewhere between Predictably Irrational, Ariely’s book and Freakonomics. It’s just full of these amazing little studies that shed sometimes kind of a strange light on human behavior, and I think it’s a great book for business people and marketers in particular, who think that people behave rationally, think rationally and the best way to persuade them is by showing them the facts.

And certainly, facts are important these days. We’ve seen sometimes a lack of facts works pretty well, but I think fundamentally, you’ve got to have your facts right before you want to start persuading, but still, there are so many other things that change our perceptions in such crazy ways. Let me ask you first, Adam, are you a member of Netflix?

Adam Alter: I am. Yeah. I’ve been-

Roger Dooley: Almost everybody else it seems these days and we probably all been watching too much Netflix in the last nine months or so, but one of their big breakout hits, was the Queen’s Gambit, about a young female chess player who starts life as an orphan with all kinds of issues and ultimately becomes spoiler alert. Sorry, a chess champion. That is a actually a great story, I thought it was very well done. But there was actually some research going back some years on that, that you disclosed in Drunk Tank Pink. What is the story on that?

Adam Alter: Yeah, and I also enjoyed Queen’s Gambit. I thought it was great. I’m a struggling chess player from way back. So, I really enjoy watching it. The research is by a group of economists who are interested in the dynamics between male and female chess players. So, most of the grandmasters have historically been men, but there have been some women who have played chess at a very high level. And they became interested in what happens when a man and a woman play and the woman is attractive in particular?

We know a lot about the way men respond to women in general. One of the things men tend to do when they’re surrounded by attractive women is they tend to behave in ways that are a little bit more risk seeking. And there’s an evolutionary explanation for this. It’s a way of sort of distinguishing yourself from the crowd. And it’s just an instinctive behavior that kind of leaks out whenever men are around attractive women.

And it’s well-recognized. It seems to be driven in part by testosterone levels and a whole lot of sort of biological mechanisms that drive that kind of behavior. And so, I think Queens Gambit, it’s interesting because the actress cast in the main role, Beth Harmon’s role, is herself a formal model even, I think she may be a model now, she’s very attractive. And the question is, is there a chance that playing against this attractive woman would change the way the players play?

And what this research found, was that looking at lots of real games, looking at the real decisions that male chess players were making when faced with women, in particular women who were attractive, they found exactly that they actually played a less well, and it was because they played very risky moves. They played risky games. Almost games that were kind of showy. And so, rather than playing solid games that would lead to the kinds of outcomes that they would like in the long run, they did silly things in the short run to demonstrate that they had sort of extra resources, that they were so competent and confident they were happy to be risk-seeking.

It’s a fascinating paper. Because again, if you ask these players, are you playing a different kind of game to impress your opponent? This is high-level chess often with a big prize purse. And so, they uniformly would say no. And yet, as I talk about in Drunk Tank Pink, a lot of the time we have no idea what’s driving our behavior, and this is one, I think strong biological example of that.

Roger Dooley: Right. One of a million examples of how people are unable to accurately, not just predict their future behavior, which is pretty difficult, but even describe their past behavior accurately. I guess one thing we glossed over was the name of your book, Drunk Tank Pink, which is really I think, a tremendous name because it immediately intrigues the potential reader, and it also is a really viewing to one of the really funny or interesting stories in the book. What is the story behind Drunk Tank Pink, Adam?

Adam Alter: Yeah. Drunk Tank Pink it’s a very bright bubble gummy pink paint color in color, that psychologists used in the 70s and 80s-

Roger Dooley: Get it on camera here for our video viewers.

Adam Alter: It’s the one in the middle there actually.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Adam Alter: That middle one is drunk tank pink. So again, it’s that bright pink color that psychologists discovered in the 70s and 80s pacified people. So, if you’re surrounded by this color, if you painted all the walls in your room but with this color, it’s supposed to physiologically suppress you. It’s supposed to make you a little bit more quiet. A little bit more compliant. And psychologists used it in the early 80s. First, they use it in classrooms, especially with unruly kids. But then they started to paint the inside of jail cells or drunk tanks. So, they take someone who was misbehaving and they put them inside the cell for 15 minutes and they found that the color being surrounded by the color pacified them or calm them down. And the term drunk tank pink was just this term of art that was used to describe the color sensitive being used in these so-called drunk tanks.

I thought it was a good emblem for what I was talking about in the book. Just as the example with Beth Harmon with female chess players. It shows that you often recognize that things shape how you behave and feel, but you don’t always realize the extent to which that happens. And I think you say to people, “Does color change how you feel and think and behave?” A lot of people say, “Yeah.” But then when you show them the extent of that, I think it’s greater than they imagined. And this pink color, I think is a really good emblem and a good example of that.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I’m predicting if this pandemic continues a bunch of pink supermarkets and such where they’re simply trying to calm down the customers who may be freaking out. Something would be a really interesting research topic I think Adam would be to check for sales of pink paint in 2020 versus proceeding years ago would not surprise me, now that your book has been out for quite a few years. That book has been out for years, it would not surprise me if there was a spike in pink paint sales.

Adam Alter: I think a lot of us could use pacifying. So, absolutely.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I wonder if pink light might even work. If you’ve got these typical builder white walls, and maybe you change out your light bulbs to pink light bulbs. And a topic that I think is really interesting for marketers, many of them are familiar with is the concept of framing and choice of words and such, and your how, the way you describe something changes the way other people will perceive it. And one, I think really great example in your book of language is how people described a car crash or how they estimated the speed of a car. Explain that, it’s such a simple but powerful thing.

Adam Alter: Yeah, the way I got into psychology, actually was, I was studying law in Australia about 20 years ago, and I became very interested in advocacy and what it meant to stand up in front of a judge or a jury, or with people you were arguing with and trying to get a point across. And I became very interested in the communicative aspects of the law. And this is a big part of it, is how do you describe an event if you’re reconstructing an event for a jury or a judge? There are lots of different word choices that you have to make. And they may seem trivial, but often they aren’t. And this is classic work from the mid 70s, by Beth Loftus, who studies memory reconstruction and memory processes.

And what she did was she had people watch a car crash, the car accident. Even even using the word crash, actually as part of the problem here. That if you watch two cars collide, you can frame that in lots of different ways depending on the words you use, you can say those two cars contacted each other, which is obviously a kind of low key attenuating form of the word. You can also say they smashed, which sounds much more intense, a little bit more violent. You can say that collided and say there was an accident. There are lots of different ways of describing how two objects might come together at speed.

What the researchers showed was that if you are reconstructing this event, so people have actually physically watched this happen on a video tape. If you then ask them how fast the cars were going when they collided or when they had the accident, the estimates of speed are tied to the words used. If you say smashed, people think the cars were going about 5 to 10 miles an hour, faster than if you say they collided. And so, word choice, they have five or six different versions of this. The word choice really matters. And it even matters to not just speed, which is hard to perceive, but objective facts.

So, one of the questions I asked people was when you saw those two cars colliding, was there glass spelt? So, did one of the windshields break? You don’t actually see that happening. But what they found was when the word smashed was used, the word smashed connotes, it suggests that there has been some glass broken or some breakage. And so, people were much more likely to misremember seeing glass broken than if the word collided was used.

So, obviously this matters a lot for the law. It matters in everyday life. It matters for marketing. It matters business. It matters in persuasion. It matters in lots of different domains. I always thought that was a very powerful effect that spoke to a lot of different areas.

Roger Dooley: I think that any time marketer can use words that are particularly vivid or sensory in nature. There’s research that shows that a sensory words tend to light up our brain in different ways than the same meaning words don’t have sensory connotations. I know that Wansink, I’m not sure if this one survived a replication or not, but he did some interesting work on describing food items on restaurant menus, and there were choosing words that were emotional or sensory, or had about five different characteristics. It would increase sales. And I think on average was 27%. To me that was a fairly believable research just because if you see successful restaurant menus, most of them do use these types of descriptive words. They all just read the research and are blindly doing it but my guess is that, they found that’s what actually sells more food items.

Adam Alter: Yeah. There’s a lot of work across domains. So, looking at the way restaurants describe food on menus, there’s a lot of work. Zillow has done some work combing their listings to see, if you want your house to sell above the asking price, what kinds of words should you use and should you not use? Are there certain phrases that are handy or less handy? There are examples from online dating as well. If you’re putting together a platform on one of the oldest sites like OkCupid. Christian Rudder was the Chief Data Scientist at OkCupid and he combed a lot of these different profiles. He basically delivered a lot of wisdom through a blog that he put together saying, “Don’t use these phrases. Don’t make your first message this one, make it this one. You’re 80% more likely to get a response.” So, I think that word choice is absolutely critical in every domain.

Roger Dooley: That’s great stuff. Marketers are kind of aware of it, but there’s such a wealth of research out there depending on the field that you’re in. So, a good part of your work in the past is dealt with the subject of fluency and cognitive fluency. And in general, fluent tends to be better. There’s research out there about stock prices. Stock names that are easier to say, have higher prices and such. But some of your work is counter-intuitive. And can you first begin by briefly explaining what fluency is and then sort of when it’s good and when it’s bad?

Adam Alter: Yeah, sure. So, cognitive fluency is basically how easy or difficult it is to make sense of any information in the world. It could be… Imagine you’re at the Oscars and you’re announcing the winner. You’ve just opened the envelope, you’re pulling out the name. There are names that are very easy to pronounce or to process, and then there are names that are much more difficult to process. Perhaps foreign names, names you’ve never encountered before, things like that.

And so, this is the fluency dimension. It ranges from very fluent, something that’s very easy to make sense of or process to something that’s very difficult or complex. And it’s not just about names, it could be how easy it is to read font. So, if you’re making a font choice, is it easy to read the words that are written in that font or is it difficult? It could be about the contrast between the foreground and the background. If I use black text on white background, that’s easy to read. If I use light gray on a white background, much harder to read.

It could be about things that are in memory. So, things that you’ve said many times over the last few months are much more likely to be at the top of your mind. They will be more fluent or easy to draw from memory than things that you haven’t thought of in years. So, if you’re trying to reconstruct an old memory that will more disfluent to process.

And so, fluency is this very domain general description of how easy or difficult any cognitive process is. Most of the time, as you say, it’s a good thing to be fluent. If you’re communicating with someone, you want them to understand you quickly. You don’t want them to have to exert too much effort. If you’re a product, you want people to immediately understand what you’re selling. If you’re in product marketing, you want them to hear the name of a book or the name of a product, or the name of the person and to immediately say, “Yeah, I understand what that is.”

So, fluency is generally, by default a good thing. But there are times when disfluency is a good thing, when in injecting a little bit of artificial complexity it goes a long way. So, if you think about the way humans function, most of the time, we kind of bumble along, not thinking very deeply about what’s in front of us, and that’s because it’s tiring. It takes up first of all, a lot of calories, but also it’s exhausting mentally for us to have to really deeply engage. That’s why this concept of deep work, this idea, you can only really do deep intensive work for a few hours of the day mentally at least, suggests that we have this limited capacity for deep thinking.

And so, our default is to go back to system one thinking, as it’s called, or to think lightly or shallowly about things. And that happens when you experienced fluency. Fluency is this sort of signal that everything in the world is fine. There’s nothing to be alarmed about. You don’t need to engage any extra resources. If you inject a bit of disfluency, so if I suddenly throw in a very difficult to pronounce word or a word you’ve never heard of before or something like that, or I stop and stutter for a second, that little burst of disfluency will cause you to go from that system one low level processing, to a higher level system two processing, where you really engage much more deeply. And so, we’ve got some evidence that if you want people to process something or pay attention to something more deeply, you actually want to make it slightly harder for them to make sense of, which is a little bit surprising to people.

So, if I ask you a question that I really want you to engage with. If I presented to you in a font, like a standard 12 point times new roman font, you’re less likely to engage with that question than if it’s a little bit grayed out. A little bit italicized, maybe a little bit condensed. A bit harder to read.

So complexity, disfluency is good when you want people to engage more. It’s also good for signaling luxury. So, if you think about luxury branding, a lot of the products we buy every day are easy for us to process. They tend to be brands that are from the country that we live in, and so we’re familiar with the language that drove those names. But if you think about luxury branding, so if you’re thinking about a luxury fashion brand, a lot of them are Italian or French. If you’re thinking about luxury car brands, again, you’ve got a lot of European names. You’ve got a lot of difficult to pronounce Scottish names, so you’ve got Lamborghini. I mean, there are all these names that are hard to pronounce it. So, we have this association between something that’s a bit different. Something that’s unique and interesting and luxury-based and being disfluent. So, if you want something to seem different and interesting, often disfluency is valuable.

Roger Dooley: Maybe the Welsh should go into the whiskey business, because I think, of all the languages, at least in our part of the world that I’ve seen, Welsh is probably the most disfluent. Some of their words are completely unpronounceable to a non-Welsh person.

Adam Alter: Right. Exactly.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Actually to add one example to what you were describing a while back. I was in a restaurant in London that had a hamburger on the menu that was I think like 26 pounds or something, not of meat, but the price. And it was a Wagyu burger and the description for that was a very long paragraph. A very faint Italic type. And it occurred to me that the association of the effort of decoding that hard to read description, kind of translates to the effort that goes into preparing that because all about, how much work the chef has to do to select the beef and prepare it. The different steps involved and everything else. So, if you want to sell a really expensive hamburger, maybe a disfluency approach could actually work.

Adam Alter: Yeah, absolutely. I think another great example of that is Häagen-Dazs Ice Cream. And so, the name Häagen-Dazs has an A with an umlaut on top of it, followed by an A without an umlaut. So, it’s H-Ä-A-G-EN. There is no language in the world that features an A with an umlaut, followed by an A without one. But this was a name that was concocted by a man in Brooklyn when he decided that he wanted to introduce a luxury ice cream to the marketplace. So, this brand is totally concocted to sound foreign, exotic, vaguely Eastern or Northern European. It’s not clear exactly what part of Europe it might be associated with.

And so, you can really take these ideas, these principles and apply them to novel examples and instances. And they’ve been really creative uses and I think the one that you described to taking the menu and introducing a slightly harder to read font, is exactly the kind of thing that we as people who are producing content for others to consume, have at our fingertips. So, we understand these principles.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I want to get onto your other book, Irresistible. It’s been a few years since that’s been out. I mean, the basic thesis is, that technology can be addictive and that the producers of that technology know that and are taking advantage of it in order to get us to consume more of their content or their product or whatever. I’m curious, it came out in 2017 and kind of two parts up, until the beginning of 2020, what had changed since then? And then secondly, how did the pandemic affect the evolution this phase do you think?

Adam Alter: Yeah, I mean, screen tech is relatively young. TV has been around for a long time. But apart from TVs, the kinds of things that we really interact with on screens every day, the smartphones, tablets are really only about 15 or 20 years old. And so, there’s been a pretty rapid evolution. When I was first interested in this topic in about 2013/2014, a lot of people said it was a storm in a teacup to argue that these forms of tech were a problem.

And now, I used to spend 20, 25 minutes in front of an audience, out of an hour long talk, just trying to convince people that we should pay attention to screens as a concern. And if I did that now, I’m preaching to the choir, I’m spending 25 minutes that I could spend on other things. So, things have really changed a lot. And I think that’s been useful. The book was really an argument for being concerned about a problem that I think now we are, as a society quite concerned with. So, that’s been a really big shift.

The other thing that’s really interesting is I had parents coming up to me earlier on, when I first published the book in 2017 saying, “I can’t get my kids to stop using screens. What do I do now?” Now What I’m seeing more of… More so in 2019, before the pandemic was, kids would come to me and say, “I can’t stand up. My parents can’t get off the screens.” So, you see this interesting generational reversal, which gives me hope. I think young people who grew up around screens have managed them in ways that we didn’t anticipate, and I think have become competent and fluent with them in a way that all the generations that didn’t grow up with it and have not, which is interesting.

So, older adults in some ways are more of a problem now than younger adults and teens. 2020 I think, with the pandemic, has done a number of things. One of the things it’s done is, I think it’s pushing people away from screens or will do when the pandemic ends. So, I think having forced people to use screens for utilities, for schooling, for work, has made screens unattractive in a way that they weren’t before. It’s makes the association between screens and these kinds of more negative, more utilitarian, more hardworking uses more prominent. That’s been quite a shift.

I think a lot of the time we spent on screens before was for leisure. A lot of the video conferencing was for leisure. Most of the work we did was in person. And I think that’s been useful because I think it means that at the end of all this, we’ll want face to face time with people. We’ll be craving that. We’ll be craving real live experiences. And so, I’m hopeful that if nothing else, it’ll push people away from screen when this year ends.

Roger Dooley: Right. Sort of the phenomenon of if you’re forced to eat pizza for year, even if you loved pizza before, maybe you’ll be ready for something other than pizza after that.

Adam Alter: Exactly.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So, I am the guy who created a website some years back that the Chicago Tribune compared to crack heroin and porn. Now I have to tell you, it wasn’t the higher ed space and it bore little resemblance to any of those, substances or topics. But one of my metrics for success, in fact, key metric was how much time people spent on my website. To me, that meant that people were getting value out of it. That I was serving their needs and that they were enjoying it and so on. And I do know that in fact, many people did benefit from it. Millions of people got answers to questions about higher education and somewhat smaller number, probably, but many tens thousands or more either got into their dream school, or found a new dream school because of the site.

So, it was basically a force for good but at the same time did chew up a lot of people’s time. And I could probably go into a few, maybe negative effects from the site, but if I look at a game designer. If I build a game, an app say, and if people try it for 60 seconds or 20 minutes and quit, and don’t come back, I failed. On the other hand, if I build such an incredibly good game that people play it for six hours every night, that’s probably having a negative impact on their lives. How does a business know how much is too much? How do you figure out where the benefit stops and the harm begins?

Adam Alter: Well, I think nuance is very important. If you’re creating a site that’s creating value for people and the more time they spend, the more value they get, that’s one thing. And I think that makes sense in the context of your education platform.

Roger Dooley: It’s partly true, Adam. Maybe not a 100%. I’m sure there were some folks who spent too much time there in rational value they derived.

Adam Alter: Fair enough. even in the gaming world, you can take different examples. If you look at companies like Nintendo, Shigeru Miyamoto was the creator of, I think 12 of the 25 best selling games of all time. He was responsible for the Mario Brothers Empire. When he was designing games, his question wasn’t how do I get people to spend as much time as possible playing my games? His question was, if I make something, will I want to play it? Will my friends want to play it? And so, it was really an act of passion and he threw himself into the process of creating these games. And the reason people play them is not because they were embedded with lots of hooks and cynical devices designed to keep us playing, it’s because they were just really good games. They were fantastic. They did what they were setting out to do better than any other games at the time.

And so, he had a knack for doing that. But now you have games that are cynical. They are predatory in what they do. And so, they do have you playing for many hours a day. But it’s not because you’re happier or feel better off or really enjoy the experience, it’s because they’ve embedded those games with a whole lot of psychological hooks that make it difficult for us to resist.

And so, if you’re a company and you’re asking yourself, what’s the metric for success? The first thing to ask yourself is what does time mean? Time is agnostic. Well, we should be agnostic about time as a metric until we know what time represents. Time could be, I spend hours and it makes me feel happy at the end of that experience and I’m enriched forward, and it prepares me better for work and I sleep better at the end of the experience, or it could be an experience that leaves me feeling impoverished, socially disconnected, exhausted. There are lots of different ways of explaining what that time, say it’s an hour, what that time means.

So, I think understanding what people are getting from your platform is really important. Even asking, “How do you feel using my platform?” Is important. One of the big innovations in time use metrics, was Moment this app that was designed to measure how long we spent doing different things on our phones. And it would ping people who had opted into the program to say, “How do you feel now using this app?” “How do you feel now using that?” And people would say, “I feel happy or unhappy.” And the app basically showed, “Well, we turns out we’re much happier when we’re using utilities.

Google maps, you shouldn’t be spending hours a day on it, but the time you spend, is time that enriches you. It makes you feel happier and better off because you can get more easily from place to place. We feel less happy when we spend a ton of time playing games or on social media or doom scrolling through news platforms, things like that. So, I think as with any of these questions, it’s really important to be nuanced and to ask important psychological questions. What exactly does the metric mean at a phenomenological level to the person who is experiencing whatever it is that you’re releasing. Whatever the product is.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, a while back there was a program. It was a virtual reality type thing, not virtual reality, but a second reality called second life. That was a sort of life simulation that people played on their desktops. And I guess it still exists, but its heyday is long past. I’m curious, we are about to enter a time when virtual reality becomes more effective, much better experience than it has been, where it’s been pretty expensive and not very good necessarily. But certainly the technology is improving. It’s getting cheaper, it’s getting better. Do you see a potentially negative aspect of that where people become so enmeshed in a virtual world that seems quite real to them that they become more divorced from their everyday life?

Adam Alter: Yeah. I think it’s certainly something to be concerned about. One of the reasons to spend so much time asking questions about in particular smartphones. So, wondering about this particular device, the extent to which this comes between us if we’re having a conversation. I think part of the reason to ask that question is because we actually want to understand what smartphones do to social relationships and communication. But a more important reason is to recognize that this is a long road. Technology is going to continue to evolve and in 10 years, in 30 years, in 70 years. Who knows what screen tech will look like? The one thing we know for sure is it’s going to become more immersive. More impressive. Processing speed will increase. The number of options for software will increase. So, in a virtual and augmented reality space, what we can do now is quite primitive. What we can do in 10, 15, 20, 30, 40 years is going to be quite advanced, relative to where we are today.

And so, one question is, if in 30 years I could ask myself, I have these little global sitting here, the latest version in 30 years of whatever the Oculus is, I can say to myself, “What is the thing I most want to be doing right now?” Is it having a conversation with three of the most interesting people from history, the AI versions of those people? Is it being on a beach in Greece? Is it walking through a particular forest that I haven’t been to, but I’d love the sights and smells. Maybe won’t even have be able to smell those experiences too at that point. Once it’s that immersive and the software is that advanced, you’ll constantly be forced to make the choice between the kind of imperfect messy complex here and now, and this perfect ideal version of what you’d like to be doing.

So, if phones can come between us and we know there’s a lot of evidence that they diminish our social connections. Imagine what will happen when it’s not the phone, it’s actually slipping something on over our eyes, going to this place that we really want to be. It’s going to be hard for us to stay in the here and now. And I worry about how that’s going to atomize people and separate them from others.

And there’s a lot of fiction about this already. Ready player one, ready player two. These classic fiction books that are really geared around this future world where people spend all of their time in virtual space rather than real ones. There’s something very dystopian about that. And so, I do think quite a lot about that and I think it’s something we should be concerned about.

Roger Dooley: Maybe at some point a few decades down the road, there’ll be a pandemic that forces us all to live in virtual reality for a year and we will emerge are ready for some real reality. We could go on forever, but I will be respectful of your time here. How can people find you and your ideas, online or social media? However you like to connect?

Adam Alter: If you just search for my name, you’ll find I have a page that has all my latest writing, whatever I’ve been working on and thinking about. My latest book, that sort of thing. You can find me on Twitter. Adam Lee Alter, A-D-A-M L-E-E A-L-T-E-R. In true to the book Irresistible, I don’t spend a huge amount of time online, but that’s where I do most of my thinking and writing in a social media space.

Roger Dooley: We will link to those places as well as both of your books, add them on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And we’ll have text, audio and video versions of this conversation there as well. Adam, it’s been great to connect after so long of not connecting. Thanks for being on the show.

Adam Alter: Thanks for having me, Roger. I appreciate it.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.