Do you ever feel like you’re not communicating as effectively as you’d like? Though we all know communication is an important and necessary part of life, the truth is– it doesn’t always come easily. Thankfully, there are tactics we can use to improve how we relate to others, as well as how others relate to and perceive us. Here today to explain more about that is Alan Alda.

An internationally recognized actor, writer, and director, Alan has won seven Emmy Awards, received three Tony nominations, and earned an Academy Award nomination. He is also an active member of the science community, having hosted the award-winning series Scientific American Frontiers for eleven years and founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University.

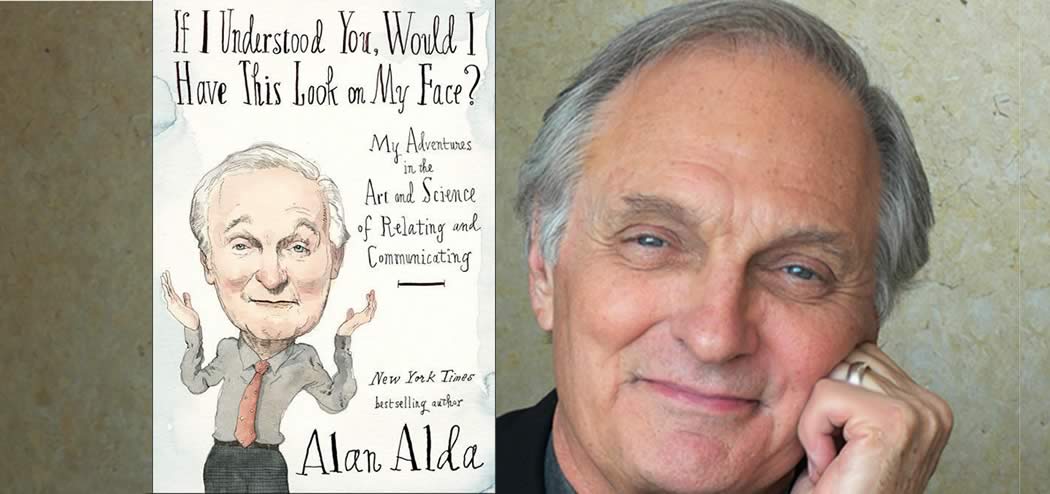

Already the author of two bestselling books, Never Have Your Dog Stuffed: And Other Things I’ve Learned and Things I Overheard While Talking To Myself, Alan recently released his third book, entitled If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating. Tune into today’s episode to hear takeaways from his newest book, as well as his advice for improving your communication.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to make people perceive you as interesting.

- What smart marketers focus on in their ads.

- Advice for conducting interviews.

- One thing Alan thinks can help all of us improve our communication and better connect with others.

- The most effective way of persuading someone.

- What “dark empathy” is and how it can be used against us.

- Tips for communicating well with a large audience.

Key Resources for Alan Alda:

- Connect with Alan Alda: Website| Twitter

- Alda Communication Training

- Amazon: If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

- Ebook: If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

- Audible: If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face? My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating

- Amazon: Never Have Your Dog Stuffed: And Other Things I’ve Learned

- Amazon: Things I Overheard While Talking To Myself

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is a person whose name will be familiar to many. Alan Alda is best known for his acting roles. He’s won seven Emmy Awards and received three Tony nominations. He’s hosted the award-winning series, Scientific American Frontiers, for 11 years and founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. He’s the author of the new book If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face? My Adventures In The Art And Science of Relating And Communicating. Alan, it’s an honor to have you on the show. Welcome.

Alan Alda: Well, thank you. I look forward to an interesting conversation.

Roger: I think that communicating is something we believe that many actors do instinctively and they’re the great at, but actually, it is both an art and a science. I think maybe a good way to intro our conversation, Alan, would be to explain your personal experience with a failure in communication that might have been a career imperiling experience of not an ender.

Alan Alda: Well, I have a few failures in communication, but then you may be talking about the terrible communication I had from a dentist once. Is that what you were thinking of?

Roger: Yes. Think of it. Dentistry has been a cut-and-dried thing and not too much of a chance misunderstanding.

Alan Alda: Well, it’s certainly a cut thing. It’s not dry. This guy had it. It was going to take out the front tooth which had gone bad. He had an operation that he involved pulling a flap of my gum down over the sockets when the tooth was gone to give it a blood supply which sounded like a nice idea, but he didn’t really explain it very well to me. He had the scalpel just inches from my face. He said this cryptic thing. He said, “Now, there will be some tethering.” I said, “What?” He said tethering. What do you mean tethering? He said, “Tethering. Tethering.” He started barking at me.

Roger: You know what a tethering is, right?

Alan Alda: I still don’t know what tethering is. As a result of that procedure because I didn’t have the wherewithal at the moment. He was in his priestly white surgical gown. I figured I guess he knows what he’s doing. I didn’t object. After the operation, I was making a movie. It was a scene where I was supposed to be smiling. Instead of that, I was sneering. My smile never totally came back because of the procedure. It makes it much easier for me to play villains now, but it would have been nice to keep my smile.

Roger: Yeah. But it’s so true. Often, particularly people who are experts or in positions of authority just assume that people know what they’re talking about, and then they get impatient with them if they don’t, but clearly, if you want to change people’s minds, change their hearts speaking in the way they understand is critical.

Alan Alda: Yeah. One of the one of the problems is not only do we often think that they know what they’re talking about. They often think you know what they’re talking about as well. This guy assumed I knew what he meant. I had no idea what he meant. He was using an ordinary English word. He wasn’t even using a special vocabulary. To this day, I don’t know what he meant. He never explained it to me.

But the thing is that it’s often referred to as the curse of knowledge when somebody assumes that you understand it with the depth that they understand and the special use they put the words to. It’s a mistake most of us make all the time. We have to guard against it. Every profession has its own private language. If we really want to connect with other people, we have to make sure that they’re able to follow us. It’s our job to make them follow us to help them to follow us. It’s not their job. If we’re trying to sell them something or trying to convince them of a point of view or just reveal to them what the facts are about something scientific or something complex that affects their lives, very important to make sure they follow us.

This sounds obvious, but it’s not that easy to do. I spend the whole book trying to show people what we’ve learned in our practice training 8000 scientists and doctors. What we’ve learned to help make that happen make the other person follow us.

Roger: There must have been an interesting challenge hosting Scientific American Frontiers because, undoubtedly, we’re talking to some absolutely brilliant people who were the tops in their field, tops in the world but may not have been able to express that in words that the layman could understand.

Alan Alda: Yeah, because they often assumed that I understood what they were talking about. I had the advantage on that program of having an enormous supply of ignorance. If I didn’t get it, it was hardly anybody in the audience left who was more ignorant than me. If I didn’t get it and I press to understand it and most of the people watching would understand it too.

Roger: It’s great. Of course, you have the benefit of editing there too where I presume you could add explainers and whatnot if necessary, but still it’s …

Alan Alda: No. That’s very good point, very good because in a live interview, I’ve done plenty of live interviews, I do have to have a road map and a structure to make sure I help the person talk about the things they want to talk about. But still, I try to make it a conversation as much as possible because … I was advising somebody in our center, our Center for Communicating Science, who’s going to start interviewing scientists on the air. My one little bit of advice was try as much as you can to ask questions you don’t know the answer to because something happens to your voice when you don’t know the answer.

If you actually do know what they’re going to say an answer to your question, all you’re really giving them is a signal that it’s okay for them to start going into a little mini-lecture. They’re not talking to you anymore. It’s not a conversation. They’re talking to the audience. I think that if you can stay together with the other person, then life happens. How do you feel about that because you do nothing but interviews? You do …

Roger: That’s an excellent point. I think that, undoubtedly, when you are able to break away from the somewhat scripted questions because I’m sure you’ve had that experience too where you go to interview somebody and they have mainly monosyllabic answers. Under those conditions, it helps to have some questions already that you can use to keep things flowing.

Alan Alda: Yeah. Well, and on the other hand is the other side to be in a conversation or an interview with somebody who says, “Tell me about your family,” and say, “Well, my grandmother died today.” He says, “Great. Now, tell me how long you been married?” Just going down the list.

Roger: I think that, sometimes, it’s usually important to have some prepared stuff just in case but, often, the best conversations happen. One, it flows more freely. Perhaps, you bring up a point that I prepared but then, from there, morphs into something else.

Roger: I think that’s especially important in a meeting where you want something from the other person. It’s good to know what you want. I think it’s … I don’t like to go into a meeting unless I have a goal. It can be a very modest goal and probably the most modest goal. The more modest, the better. I hope this leads to another meeting so that we can lay the groundwork for trust between us and that kind of thing, but whatever happens, if I’m not sensitive to what’s really happening in the moment with the other person, I might be missing hordes of opportunities. If I let the conversation go based on my real interest in what the other person is saying, the other person might start telling me a story about something that has nothing to do with our meeting but that I’m very interested in it and then that I’m very engaged in.

Suddenly, we might find we have a point of contact we didn’t expect we had. That commonality, I think, it’s been shown in a number of research efforts that when you have that commonality, and often it happens by accident, there’s more trust, and there’s more of an ability to collaborate and really communicate on a scale that’s much more workable.

Roger: Well, I think you’ve taken it from the interview situation into the more personal communication, say, in a meeting. Of course, that’s something I think most of our listeners have to deal with for better or for worse. One of the classic pieces of advice about conversation is that people perceive you as being really interesting if you’re a good listener.

Alan Alda: Yeah. Boy, if you’re interested in them, then they’re interested in you.

Roger: People say, “Yeah. He was such an interesting person. What did you talk about?” Well, I told him about this and that because he was interested. It’s probably something that can have a lot of benefits in business. I think one thing that I could throw in too is that when you listen to the other person, you find those areas of commonality that you have that you might not have realized. That in turn is a really powerful tool of persuasion. If you find that you’ve got something in your background in common whether it’s school or family or ethnicity or that you both lived in Cleveland at the same time, that can establish what Robert Cialdini, the persuasion and influence guru, calls liking. But you don’t find that out unless you’re listening and paying attention too.

Alan Alda: Yeah, and especially looking at the other person. That’s amazing how many conversations take place with our attention not on the person but on what we’re trying to say. Then, we’re looking off sometimes. I see some people talking to each other with their head at an angle that it is like 45 degrees away from the person they’re talking to. You pick up so many clues from the person’s face. It’s not a good idea, not to watch and respond to the face moment by moment.

When you do, when you find this moment of commonality, there’s something happening to the tone of voice that wasn’t there before. The tone of voice gets more personal. It sounds more like two living people talking to each other. They don’t sound robotic where they’re just reeling off what they had planned to say. It’s not a real encounter if you just memorize what you want to say and dish it out to the other person, I don’t think, because I might as well send them an email. But this personal encounter is rich with possibilities if you’re really paying attention. I didn’t mention this in the book. It just occurred to me this observation I’ve had.

So many times, I had a lunch. Check this out with your experience too. Being in a dining room at lunchtime, and I hear the drone of conversation and table after table would be filled with people having business conversations. They sounded a little robotic to me each time I heard this. There was a level tone. The tone of voice didn’t have the ups and downs that it has when people are connecting socially and trading words with each other rather than making alternative monologues.

That sound to me is an indication, I may be wrong about this, but it sounds to me like they’re not really exchanging bits of themselves. They’re just having what you could call dueling monologues.

Roger: I think it relates to the way people think where the numbers vary, but the number that I like to use is from Gerald Zaltman from Harvard that 95% of our thought processes and decision-making processes are non-conscious, and only 5% conscious. But what you’re really trying to do when you’re in that semi-robotic business pitch mode is you’re really only dealing with that rational logical part, the conscious part. You’re really missing both non-conscious part, the emotion, and so on that goes with it.

That’s why the advertisers use emotion in their ads and ads that just to emphasize product features generally aren’t very effective and maybe in a few settings they work if you’re selling industrial machinery, but in most cases, the smarter advertisers and marketers focus not just on the futures which may be important but on the emotion and so on. I would guess that applies to conversations too.

Alan Alda: I think it does. In fact, I was talking to a scientist just last night who was concerned that he was having a hard time getting his climate change message across to a lot of people. He was concerned by the research that he’d read that showed or suggested that telling people the facts doesn’t necessarily change their minds in any way or make them more available to what you have to say but making contact with them in a more human way finding out what your commonality is establishing trust. Trust is really important. You don’t necessarily establish trust by telling people facts alone including the fact that I have this degree and I know more than you. That’s not a fact. That’s easily accepted by a lot of people.

Roger: Yeah. Well, if you look at the case of the vaccine deniers, I think that’s probably a perfect example of what you’re talking about where the scientists go out with all those statistics showing that vaccines are safe, but they save many lives that the risks are absolutely minimal and so on. But then you get one mom who goes on TV and tells her story about her kid who was diagnosed with autism three weeks after he was vaccinated. That carries much more emotional punch. It’s actually much more persuasive for many people.

Alan Alda: That’s right. We all tend to go with the influence of people we trust including those of us who are really interested in science. When you think about it, I trust that if I read an article in the magazine science or nature, I trust that that research study has been vetted by competent scientists and that the research protocols were done properly.

When I talk about that research and rely on it for decisions I’m going to make about my own health or fitness or medical condition, then I’m operating to a great extent on trust. I think I’m rational about trusting them, but it’s in some ways similar to somebody who trusts her Aunt Tillie because Aunt Tillie so far has lived a good long life and has seemed to make good decisions and has this opinion that’s not backed up by research, but you can trust Aunt Tillie in a way we all have an Aunt Tillie, but we have to try to be as careful as we can about putting our trust in the right people.

But if you want to o get somebody to pay attention to what you have to say, not necessarily to convince them of it, just to hear your story and then enter into a conversation about how it applies to them, what’s best for them and that kind of thing, then I think you have to establish a certain amount of trust. That takes a little vulnerability. You can’t say, “Look, Jack I know, and you don’t.” Pay attention. It’s not going to work, I don’t think.

Roger: I think you mentioned the word the story there too. That’s a pretty powerful tool for communicating and again the power of … You can read Consumer Reports and say, “Well, now, Toyota makes by far the most reliable cars.” I don’t know if that’s true these days but if your neighbor had a Camry that was a total lemon, that’s probably going to be a bigger influence on you than the much more reliable statistics in Consumer Reports.

Alan Alda: Yeah. Absolutely, because for one thing, when any claim is made in a piece of advertising, we all know that they’re pleading a special case. They’re telling you pretty much what you need to know to buy the product and not saying. On the other hand, some of our cars fall to pieces. This is not going to mention that. They remember that time when cars were blowing up because they had rear-end collisions. I forget what the exact …

Roger: Tthat was that was the Ford Pinto. I forget what year. That was a while back.

Alan Alda: Yeah. They didn’t mention that in any of their eggs. I don’t even know if they talked a lot about fixing it because that would bring up the subject that they had a problem to fix, but in in real time conversation, I love it when somebody says to me, “Here’s what I’ve learned. Here’s what I think I’ve learned. Here’s why I might be wrong about it.” But the preponderance of evidence to me seems to be this. Boy, I listened to them a lot more closely than somebody says, “Here’s what I know, and it’s what you ought to know if you know what’s good for you.”

Roger: Well, let’s get on to your book a little bit. It’s a great guide, very readable and, of course, it’s a book about communication should be. But what do you think how the most important takeaways are for the reader? I’m sure you speak occasionally. You can’t quite deliver all the content in the book. What are what are the most important takeaways?

Alan Alda: Well, I’ve very cleverly been talking about that the whole time we’ve been talking without mentioning the book so that it’ll sound like I’m repeating myself.

Roger: Hey, this is this promotion 101, Alan. You’ve got to mention the book. Say, “Yes, I say in Chapter three.”

Alan Alda: Well, as I say in the title of the book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face which is the title, book is based on the notion that empathy is a really important part of communication. I doubt that you can have good communication without empathy. By empathy, I mean an awareness of what’s going on in the other person’s life and mental life especially the emotional part and also to try to figure out what they’re thinking while you’re talking which you could call theory of mind.

Without those two things, without an estimate of what they’re going through, I think it’s very difficult to be able to get them to understand what you’re trying to explain to them especially if it’s complex if you’re trying to talk to them about it a financial instrument or pretty much anything about how to redirect their nutrition or something like that. There’s a real difficulty. If you’re not paying attention to what’s happening on the other person’s face and the other person’s tone of voice and that’s the viewpoint of the person speaking in the title of the book.

Well, what makes you think I can understand you if you’re not paying attention to this look on my face that’s telling you I don’t know where we are in this conversation? There are many ramifications to that if we fill up a book. It’s not just that one thought, but that’s the general theme which is how do you get that empathy because almost all of us have a capacity for it, but it tends to dribble away. You have to keep getting booster shots. What can you do to maintain empathy? How can you use the empathy to really communicate with other people?

I don’t see how you can get things done without communicating. You can’t have good teamwork. Sales can’t happen. Employee-employer relations can’t happen. It works in both directions. The employer has to be aware of what’s happening in the mind of the employee and the other way around for sure because you’re not going to get hired. You’re not going to get a raise. You’re not going to get more resources for your team unless you can communicate really well what the situation is. That’s what I found in talking to many people who are expert in this and in the years I’ve spent teaching scientists and doctors and nurses to communicate better.

In the past eight years, the art center for communicating science has trained over 8000 scientists and doctors across the United States and in four or five other countries. This is not just coming out of the blue. It really comes out of science and experience. At heart, it’s applying all of those factual ideas to the art of communicating because at the heart of it, I think it is an art, but you can really sharpen up to yard and science it up and make it more valuable and effective.

Roger: Now, what is dark empathy?

Alan Alda: Well, that’s my name I use for empathy that’s not so good for people. It depends on how you define empathy. I realized a lot of people feel that empathy is the same as compassion or wanting to treat people well. I don’t think so. I think you can have empathy and not have any compassion for the person you’re dealing with.

Roger: Good comment probably as the kind of empathy.

Alan Alda: Psychic palm reader, they’re watching your face. But I’ve interviewed a number of them. They have a technique. They watch your face really carefully. They listen to the little grunts you make as they talk about something at random. If they hear, if they see that you’re lighting up, it’s something that they mentioned randomly, they wait five minutes. They talk about others stuff. Then, they come back to that random thing like they saw you light up when they mentioned somebody with dark hair. Then later, they come back and say, “I guess I see it now. There’s somebody with dark hair in your life.”

Now, the person says, “Wow. Where’d they get that from? Well, they got it from your face. That’s an example to me of dark empathy. Interrogators use it to make a person feel helpless. They know exactly what you’re going through emotionally. They play on it. It’s not always in your best interest. The same thing is true for bullies. I think bullies know how you feel. They use how you feel to make you feel worse. It’s possible to use it. For me, it’s pointing that out is a way of pointing out the fact that empathy is just a tool, I think an essential tool for communication and one that you can improve on.

There are people who teach empathy. We, and the work we do at the center, I think we raise people’s level of empathy. It helps in the very basis of communication.

Roger: Well, I think it’s probably like many other things. I’m constantly asked this since a lot of my work it has to do with influence techniques and so on. There’s a lot of good science there. People who will always ask, “Well, is this ethical?” It’s really the way that you use it. If you use this knowledge to deceive people to get them to buy stuff that they don’t want or they’ll regret a day later or a week later, then no. That’s wrong. That’s unethical. But if you’re helping them get to a better place, then it’s a good thing. Empathy, I guess, is no different. If you have that ability to establish empathy, you want to use it for good purposes not evil.

Alan Alda: It doesn’t mean we should never have discovered radioactivity and in the same way to place newfound attention on the value of empathy and communication and even influencing people. It doesn’t mean that because it could be misused that it should never be used. On the contrary, I think we have an obligation to ourselves and to the people that we’re doing business with when we do business with people to do what, as I remember Daniel Goleman pointed out, makes for a good salesperson which is you find out what the person who you’re selling to really need even if they don’t fully see it themselves, not only do you concentrate on what they want.

But if you see that they would be much better off with something that they truly need and that might not even make you as much money as what they want or what you’re trying to get them to what, but you satisfy their full need, then you don’t just have a customer once. You have a customer for life in all likelihood because you’re putting their interests at heart. The same thing goes for influencing them and using empathy. If you don’t use empathy in their interest and you’re only using it in your interest to their detriment, there’s something not only wrong about it, but it’s not in your interest either.

Roger: No. It’s a short-term tactic. If you persuade somebody to do something that’s not in their best interest, that’s going to be a one-time sale probably where the really effective salespeople do exactly what you’re suggesting. Goleman, for our audience, is the emotional intelligence guy and really the guy who started that whole movement.

Alan Alda: Yeah, very valuable guy, I think.

Roger: Let’s change gears just a little bit. We’re talking an awful lot about the in-person communication. We are sitting across the desk from somebody or perhaps in a meeting. What about where it’s one-to-many communication say if you’re speaking to a larger audience or doing something where you can’t necessarily see the gauge the individual reactions very well? Sometimes, you can actually do that. If it’s a small audience and the lights are up in the house, you can engage with people pretty well. But other times, you feel like you’re just alone out there talking.

Alan Alda: Yeah. That’s a terrible feeling. It’s not a good feeling. When I talk to a big audience, a thousand or 2000 people which I do from time to time, I asked the technicians to, please, bring the lights up to about 25% or 30% something. They’re still focused on the stage where most of the light is. But there’s an ability for me to see my other reacting. I can actually look into the eyes people in the audience.

What we do in our training when we train scientists to communicate better, a lot of it is one-to-many. What we do is we spend a lot of time teaching them communication through working on improv exercises, improvisation exercises, not to make them actors and not to make them comedians. The point of these exercises is to get them in the habit of making a close personal connection with the person they’re doing the exercises with.

Then, when they turn to the audience, they’ve got that habit of talking in a personal tone of voice. There’s an intimate connection that’s actually possible between one person and hundreds of other people listening. You hear it in the tone of voice. You see it on the face. You see it in the willingness to get out from behind the fortress of the podium to put down the written material and talk from the heart. If you’re talking about something you’ve spent decades studying and you can’t just talk about it as if you really know what you’re talking about, there’s something wrong if you have to repeat every word of it. The worst example is to turn your back on the audience and read your PowerPoint at them. I love what somebody said once, “Power corrupts and PowerPoint corrupts absolutely.”

Roger: There are there are different techniques. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen Lawrence Lessig use PowerPoint but he’s a virtuoso of timing in a 45-minute keynote. He will have hundreds of slides. They’re just a visual punctuation of what he’s saying. But of course, the more typical use is five-bullet points on a screen or big table full of data that nobody in the audience can read and saw their similar abuses.

Alan Alda: Yeah. Sometimes, it’ll be almost a whole chapter of something up on the screen. Then, I find if the person giving the talk reads what’s on the screen, it becomes almost entirely unintelligible because the audience is trying to read it with their eyes at the same time they’re hearing it with their ears from the speaker. The tooth aren’t totally in sync, and you have a conflicting signal. I really would say unless you have a picture, and I realized this contradicts the expert you just mentioned, but I would make a suggestion that if you can be personal with the audience and conversational with the audience, really make contact with them.

I wouldn’t show anything on the screen unless it’s a picture or a video that’s absolutely essential to show because they wouldn’t understand it without that or if you’ve got three incredibly important points. I don’t know how you can do it more than three because I don’t think anybody can remember more than three things or at least it’s hard to. Then maybe put them up. I would really cut way back on having people look away from person talking because if you can involve them, engage them in interesting stories and authentic talk about how you got to where you are in your thinking or in your life, I don’t think there’s any picture on the screen or any words on the screen that can beat that. But you’ve got to really make contact with them. You can’t just recite but you decided to say to them.

Roger: Right. It makes a lot of sense, Alan. I think that different techniques work for different people. There is some evidence that when people see information visually, it’s more memorable. At the same time though, you just use the S word again, Story. Stories are probably even more memorable. If you can encapsulate your key points into stories, that’s what people will really remember from your talk. Let me just ask one final question here. You’ve got a lot of science in the book. Is there anything that as you were doing the research for this it really popped out as being a surprising finding that you didn’t expect? So much science as well, we knew that, but now we’ve got proof. Do you find anything that was a really a surprise as you’re doing the work for this?

Alan Alda: I was surprised. I don’t know if it fits in with the interest of your audience. But this is an example of not directing the conversation but seeing what comes up. The honest answer to your question is I was very surprised to talk to a scientist who had used improvisation exercises to help autistic people relate better to events that and people that they came across in the outside world. He could do remarkable work with them.

I was interested in that because we use improvisation, as I mentioned, to help scientists and doctors and everybody else we worked with to connect with other people better. He was able to help autistic people who have problems connecting especially when things happen in an unexpected way which is the way things happen. Nothing happens in an expected way pretty much.

I was really surprised at how effective it was even with that population. It only reinforced my belief that it helps all of us in every way to the whatever practice we can make in contacting other people and letting to be a two-way street between us, the better off we’ll both be.

Roger: The improv is an interesting point. I’m certainly not an expert, but as an outsider who has never actually done it, it seems like a creativity exercise. In other words, somebody prompts you with a word and how quickly can your brain come up with something amusing to do with that and a mental quickness thing but actually, it’s also about the interaction with other people and feeding off each other. That’s really what you’re getting at, I think.

Alan Alda: Yes. That’s the basis of the creativity part. It does help you be more creative. Oddly enough, as it develops your empathy, empathy has the side effect of not only putting you in touch with what the other person is feeling. It puts you in touch more with what you’re feeling. You’re more able to let thoughts and feelings and ideas rise from your unconscious which is where they come from when you’re working creatively so that this creative process improves oddly enough with your focus on the other people. The social connection is very important for this. This is backed up by a bit of research that that makes me confident to talk like this.

Roger: Great. Well, just in case there’s a few listeners out there who don’t recognize your voice, Alan, let me remind them that we’re speaking with Alan Alda, award-winning actor and author of the new book If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look On My Face. Alan, how can people find you and your content and information on your training online?

Alan Alda: A number of ways. I started a corporation to help train in companies that do science and also to train at the executive level and all the proceeds from that company go to the Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. The company is called the Alda Training, I’m sorry, the Alda Communication Training Company or ACT, A-C-T. You can look up at that. You can look up to the Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook. You look Alan Alda in communication, you’re going to trip over one way to find out more about it.

Roger: Great. Well, we will link to those places and any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. I also have a text version of our conversation there too. Alan, thanks so much for being on the show. It’s been a real honor.

Alan Alda: Thank you, Roger. I enjoyed our conversation, and thanks for making it a conversation. I really appreciate that.