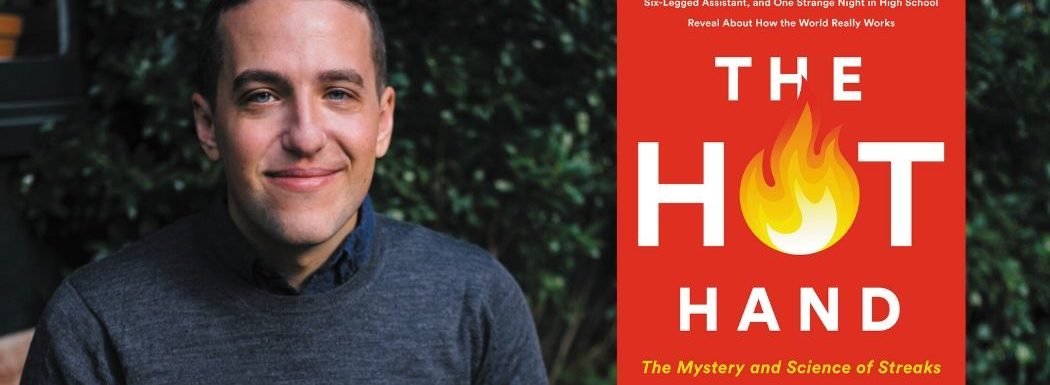

Ben Cohen is a sports reporter for the Wall Street Journal who writes about the NBA, the Olympics, and other topics that don’t involve extraordinarily athletic people. While he is definitely the first sports reporter to join this show, he may also be the first sports reporter to write about behavioral science and cognitive biases.

In this episode, Ben covers both of those topics and more as he shares insights from his new book, The Hot Hand. Listen in to learn about the science and mystery of streaks, how The Hot Hand Fallacy may be faulted, and how to differentiate between random and skilled performances.

Learn about the mystery and science behind streaks with @bzcohen, author of THE HOT HAND. Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How we all see patterns in randomness.

- Why we have to embrace The Hot Hand Fallacy.

- The science behind streaks.

- How Ben combined sports and psychology.

- The difference between random and skilled performances.

Key Resources for Ben Cohen:

- Connect with Ben Cohen: Website | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Amazon: The Hot Hand: The Mystery and Science of Streaks

- Kindle: The Hot Hand

- Audiobook: The Hot Hand

Share the Love:

- If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

- Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley.

I’m quite certain that today’s guest is the first sports reporter we’ve had on the show, but he may also be the first sports reporter who’s written a book about behavioral science, cognitive biases, and other topics we often discuss here. Ben Cohen is a sports reporter for the Wall Street Journal. He writes about the NBA, the Olympics, and other topics that don’t necessarily involve extremely athletic people, and his new book is the Hot Hand, the mystery and science of streaks. Welcome to the show, Ben.

Ben Cohen: Thanks for having me. What a pleasure to be the first sports reporter on the show.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well I guess it depends. If this was ESPN, it would be no special thing. But since we talk about things like behavioral science and neuromarketing and applying psychology to business, a little more out of the ordinary.

Ben Cohen: Yes. I’m not sure ESPN has cognitive psychologists on all the time either.

Roger Dooley: No, that’s true. And maybe they should, especially after people read your book. They would probably … undoubtedly they are totally believers in the hot hand and streaks. But let me start off Ben … and as we’re recording this, we are not quite there yet, but we are approaching the time of NCAA March Madness, which for our international listeners, is the very popular US college basketball tournament that determines the national champion. And you’re a Duke alum and this seems to be kind of a rare year when they aren’t unbeaten or almost unbeaten. How do you think they’re going to fare?

Ben Cohen: Well, the beauty of the NCA tournament is that it is incredibly unpredictable, right? It’s a single game elimination tournament in which anything can happen and often does. And so when you are a fan of maybe the best basketball team in the country, that’s not always great, because you actually would prefer something like the NBA playoffs where there are four rounds and a best of seven series and the best team usually wins. However, this year, Duke is not the best team in the country and that means that it’s open for uncertainty and lots of crazy things can happen. And so this year is actually not the worst year to be a Duke fan because the NCA tournament is random. And the reason it’s so mad is that anything can happen. And so it could be worse, right? They could be by far and away the best team in the country and they’re losing the NCAA tournament. That’s worse than the other option.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I guess there’s something kind of similar in the appeal of soccer or football to folks outside the United States where there seems to be a pretty big random element to … the best team doesn’t always win because in games that are decided with scores like one to nil, that … a lot can happen. You can get a penalty, you can have a freak shot and really upset things. So I guess some people like that, some people don’t. I always find it kind of strange when the best team didn’t really seem to win that game. Even though they played better, they didn’t win. But at the same time, it is sort of an equalizer where you may not have talent parity I suppose.

Ben Cohen: That’s right. And the structure of something like the English Premier League is kind of anathema to everything we know in American sports, right? There are no playoffs. It’s the team that has the best regular season record wins the championship. And it puts this incredible value on coming to the stadium every day and placing utmost importance on every time you play.

Ben Cohen: That’s not the case necessarily in the NBA, in the NFL, certainly not major league baseball where there are 162 games. But the beautiful thing about the NCAA tournament, in my estimation anyway, and this is about to be a very, very shameless plug, is that one player getting hot can take you pretty far in to the tournament. When you have a sample size of one game, when 60, 80 possessions is what is going to determine whether your season is over or whether you’re going to keep playing for a championship, one player getting hot for a few minutes can actually make the difference. And there are few places better to sort of study the power of the hot hand than the NCA tournament. We’ve seen it before, we will see it again. We might even see it this year.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So I’m curious, and just to back up briefly, because I do want to get to the idea in the book, but I’m curious, did you discover psychology and behavioral science while you were still an undergrad or is this something that developed really through sports and your looking at streaks and hot hand that drew you into it, or a little bit of both?

Ben Cohen: It’s a little bit of both. So the truth is that this is kind of a book … as much as it’s about sports, it’s about economics and psychology and statistics probably. And when I was in college, I did not take a single class in economics, psychology, or statistics, which I regretted as soon as I graduated because when I came to work for the Wall Street Journal and to write about sports and to really apply data to sports and study this very subjective endeavor in a more objective way, I realized right away obviously what use statistics and psychology and economics and computer science would be in writing about sports. They would be far more useful than my lousy English degree from Duke, right? But I’ve always had an interest in this sort of thing. I don’t really know where it comes from. Maybe part of it is being a sports fan and a sports reporter where psychology and statistics have become increasingly prevalent in school since Moneyball came out in 2003.

Ben Cohen: And I am of the age where I read Moneyball at a very seminal … I read Moneyball at a very formative time in my life and so I didn’t really have to change the way I thought about sports. This sort of was the way I thought about sports. And in the book, I write about a couple of people around my age who have contributed some really interesting papers to this field of hot hands studies, and they’re kind of the same way. They read Moneyball when they were in middle school and high school, and that way of thinking about sports, of rooting decisions in data and always looking for objective information, that was the way they thought about sports and that really applied to the hot hand. So to answer your question, it’s a little bit of both. I had this natural fascination with this world and I’ve seen it become more important in sports over the last decade.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yep. So one of the fundamental concepts that underlies your book, Ben, is that humans and even other creatures tend to see patterns in random data. It’s a cognitive bias that Tversky and Kahneman wrote about. And so if we’re flipping a coin and we get four heads in a row, some people might say, “Well boy, it’s really likely to be a head the next time because we’re on a streak, or that’s how the probability seem to be going.” If we’re a little bit more rational, we can say, “Well, no, it’s a coin. It’s 50/50, so it’s got equal probability of being a head or tail the next time.” But when it comes to Steph Curry making four baskets in a row, we immediately assume that he’s in the zone, he’s got the hot hand and is probably going to keep making baskets. Right?

Ben Cohen: That’s right. And I think you really hit the nail on the head. I mean, all of this really started in the 1980s with this first classic study of the hot hand by Tom Gilovich, Bob Vallone, and of course the great Amos Tversky. And what made this paper so classic was the counterintuitive conclusion, which is that there is no such thing as the hot hand. It was this cognitive bias, this very easily digestible example of seeing patterns in randomness. It was our brains playing tricks on us, right? But something amazing happened after that study, which is that it was so unbelievable that many people just refused to believe it. We’d all felt the hot hand, we’d seen the hot hand. And even when this evidence was presented by some of the smartest people on earth, we just wouldn’t listen to them. And that’s actually what drew me to the hot hand to begin with. It was a story that I could write in which the main characters were genius scholars and Nobel prize winners and NBA superstars. And that doesn’t really come along very often and it proves sort of irresistible to me.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So there’s been a replication crisis in psychology and social sciences. How did the later studies fair when other people tried to study and prove that there wasn’t a hot hand?

Ben Cohen: Yeah. People have been looking at that paper over the last 35 years, basically ever since it was published, because basketball fans and players refused to believe it. What psychologists and economists did was try to figure it out for themselves, right? It launched this field, this great scientific literature, about the hot hand. And for many years that paper held up. It was bulletproof. What has happened in recent years, the first is that there have been some accusations that the original paper was underpowered, that even if there were a hot hand, they didn’t have enough data or computational power to actually detect it. But what’s really changed in recent years, and this is kind of why I wrote the book, is that we have come across some new evidence, powered by new data and new ways of thinking about that data and this very old problem about the hot hand to suggest that our intuition actually may have been right all along and that there really might be such a thing as the hot hand.

Roger Dooley: Well, it seems a little bit intuitively appealing. I know you have an anecdote in your book about a basketball game where you performed way above your normal level and seem to have that hot hand. I’m not a great athlete, but I have played rec ball in the past and I’ve had an occasional game or day where it suddenly seemed that my shots were just hitting right, stuff that I could not do on a normal day. I’m was normally a pretty mediocre player, but I would have a really amazing day. And you think of things like flow states that are apparently well documented and muscle memory where there’s not a conscious thought process going on. You’re performing at a more or less automatic level. So I mean, it seems like there is some kind of reality there. I guess where does the reality end and the misperception begin?

Ben Cohen: I think it’s one of the great mysteries and it’s why people have studied the hot hand and been compelled by the hot hand for so long. As you said, when I was in high school, I scored more points in one quarter of one game than I scored in my entire high school basketball career combined. And that actually says a lot about two things. It says a lot about what happened in that game, which is that I really couldn’t miss. And it also says a lot about the rest of my basketball career, which is that I was pretty terrible at basketball.

Ben Cohen: But I have this very clear vision of this very strange event in my life because it has just stuck with me. And what I’ve learned while writing this book and since publishing the book is that it’s actually not that strange. People have this feeling and they remember their own hot hands, which has sort of contributed to the public’s understanding about the high end. Can I ask you, Roger, do you have like clear recollections about those few basketball games when you did feel like you couldn’t miss? Do you remember everything about them?

Roger Dooley: Oh no. Well a little bit. I remember more about those than other games. And of course I think that’s one effect. If you flip coins every day, you aren’t going to remember all the days when they came out pretty close to even.

Ben Cohen: That’s right.

Roger Dooley: But boy, that one day when you threw a whole bunch of heads or tails, you can say, “Wow, I remember that day with a lot of detail.”

Ben Cohen: Also you have to be fairly interesting to begin with to be someone who flips coins every day, right? But Roger, do you remember though, walking off the court and feeling like there was a hot hand, like something had been different that day while you were playing basketball?

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it was rec ball actually. But yes, I mean I just felt that, to use a common term, I was in the zone, that without really thinking about how I was moving or swinging or whatever, that I was just doing it right compared to most of the time when I had great difficulty in doing it right, at least on a consistent basis.

Ben Cohen: Right. So there’s a basketball player who’s slightly better than both of us at basketball and his name is Stephen Curry and he’s one of the greatest players and he’s probably the best shooter in the history of basketball. And I’ve talked to him about the hot hand and he doesn’t know when it’s going to happen or where it’s going to happen or even why it’s going to happen. But what he says about the hot hand is that once it does happen, you have to embrace it. And I think that’s a really interesting way of thinking about all of this. Now the tricky part, and I think kind of the fun part is this inherent mystery of figuring out when you can embrace it. And I think that’s when we get to this question of does the hot hand exist? Should you believe in it or is it a fallacy, right?

Ben Cohen: And I think the crucial distinction is one of control. So when we feel that we have agency in a situation, such as when we are playing basketball, when the ball is leaving our hands, we feel like we do have the hot hand. But it’s important to differentiate between skilled performance and random performance. There are certain industries where it’s actually not possible to have the hot hand and believing in the hot hand can be disastrous. It can come back to burn you, so to speak. So skilled I think is when you can take advantage of the hot hand and random is when you’re at the mercy of chance. And it can be just as important to recognize those random situations because you don’t want to believe in the hot hand. It can really backfire on you.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, you work for a publication that does not focus on sports most of the time, but rather on business, and I’m curious how you see this effect manifesting there. I mean, business publications in general tend to love to write about the fund manager who’s had a string of successes or a business leader, a CEO, who’s had a couple of … or several successful turnarounds in a row and that sort of thing. Again, I think you have this distinction between, “Okay, maybe sometimes people are better managers or leaders or investors than others, but there’s also a huge randomness effect there.” How do you see this manifesting itself in what your colleagues are writing about?

Ben Cohen: Yes. The brilliant people around me who don’t bother with sports. No, I think it’s a very interesting question and I think the question of how the hot hand applies to business is the billion dollar question. In the book I read about this firm called Dimensional Fund Advisors, which was founded by this billionaire named David Booth. And Dimensional has really been at the forefront of the passive investing revolution that has swept through finance in recent years. And most people on Wall street probably believe that you can get hot, right? There is a hot hand. And in fact they are the people who are hot, right? They want you to give them your money because they can beat the market. They’ve done it a few years in a row and they have uncovered some secret and it has resulted in a hot hand. David Booth doesn’t believe that. He studied under Eugene Fama at University of Chicago at the time when Fama was beginning to unveil his thesis that markets were inherently efficient, right?

Ben Cohen: And this was a deeply radical idea at the time. It’s become conventional wisdom today, but it was super counterintuitive back then. And what Booth did with Dimensional was sort of let the markets go to work for him instead of believing he could beat the market. What he says is if you look at what the fundamental question in investing is to this day, even after all this research, it’s still are there hot hands in stock-picking? And he says the best working assumption is no. Now that doesn’t mean that people can’t get hot because we know that they can. It’s just that it’s hard to identify them before the fact and it’s silly to believe that you can be the person who will identify them before the fact. And I have to admit, I could’ve written about anybody in this book, especially anybody in finance on either side of the hot hand, someone who believes they can get hot or also someone who believes it’s silly to think that they can get hot.

Ben Cohen: But the reason I wrote about David Booth is that he has this very odd connection to basketball and I found that most people in the field of the hot hand do have some connection to basketball because basketball happens to be this wonderful excuse to explore the rest of the world. A few years ago, as you might recall, or not, the original rules of basketball as written by James Naismith, the game’s inventor, were sold at auction. And who bought them for a few million dollars? None other than this investor who doesn’t believe in the hot hand named David Booth. He spent part of his fortune to get the rules that James Naismith wrote about basketball many hundreds of years ago. So I thought that was a very cool little odd connection that was intriguing to me.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). So I mean I guess there are people like Warren Buffet, who, I don’t know if you would say that he has a hot hand, but he has produced outside returns consistently over multiple periods. He’s definitely not sort of a random walk success story that wow, hey, just turns out that he was successful and his peers weren’t, I don’t think. What do you think?

Ben Cohen: Well I don’t think so either. But even Warren Buffet, probably the greatest stock picker in the history of the universe, he also has complicated feelings about the hot hand. In his will, he lays out these explicit instructions for how to invest his fortune when he dies. He says, “Put 90% my money into a low cost S&P 500 index fund.” And he even had a bet with a hedge fund investor about 10 years ago in which he sort of encouraged anyone who was willing to take the other side of this $1 million bet to put together a fund, a portfolio of any hedge fund they wanted, tweak it as much as they wanted. He was almost encouraging these people to chase the hot hands, to figure out where they could beat the market every year.

Ben Cohen: And on his side of the bet, he would take a low cost index fund and not look at it again over the course of 10 years. And what happened? They called the bet off a year early because it was such a route that the other guy couldn’t possibly catch up to Warren Buffet. He put his wallet where his mouth was and it paid off tremendously for him as it tends to do for Warren Buffett.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and I guess you could also say that Buffet himself isn’t a hot hand type of investor. He’s not placing a bunch of similar bets that he thinks are going to be immediate winners. It’s just more of an almost consistent exploitation of maybe small differences in valuation that over time have paid off really well for him. But I guess we can look at mutual funds or ETFs and such that end up getting folded if they’re losers so that the remaining ones look good for potential investors.

Ben Cohen: Right, there’s a survivor’s bias.

Roger Dooley: So when your fund company says, “Hey, look. Look at the returns for this fund over the last 10 years and how they’ve outperformed whatever the market metric is that they’re trying to outperform,” they don’t tell you about the ones that did not do that and just kind of quietly went away.

Ben Cohen: But Buffet is also an interesting example in another way, right? Because people know who Warren Buffet is. He has opportunities that the rest of us peons do not have. And he’s able to take advantage of those opportunities. He’s able to take advantage of when circumstance bends his way. Now, his circumstance has bent his way for a very long time, but it’s actually not all that dissimilar from someone like Steph Curry or any other basketball player. When you feel hot, your team will run plays for you, right? Your teammates will try to get you the ball and it suddenly becomes permissible and actually kind of acceptable for you to take shots that you wouldn’t take otherwise. You can take riskier shots and longer shots and harder shots and sometimes those shots go in and they elevate you to this other plane where people start to see you a different way. So I think that’s actually kind of the power of the hot hand. It’s sort of this way in which success begets success and you can actually use it to create even more success from there.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). And sometimes I guess … I don’t know, how would you describe the Dan Brown phenomenon, the author of the DaVinci Code, where at one point he had three books or maybe more on the New York times bestseller list, which is a pretty phenomenal achievement. And really what drove that was … I mean it looks like maybe a sort of hot hand situation, but it was the popularity of one book, the DaVinci Code, that ended up elevating the popularity of the other ones. Is that a pretty common scenario?

Ben Cohen: Yeah, I think so. I think in the sense that he was able to turn one hit into two or three hits. And that’s sort of how I think momentum works in this sense. So in the book, I didn’t write about another author. I wrote about a movie director named Rob Reiner, who most people know by now because he has directed some of the most beloved films in Hollywood. And he sort of followed a similar pattern. The first movie he made was This Is Spinal Tap, which nobody wanted him to make. He had to drag his demo reel all across Hollywood until he finally found the very least amount of funding that would be acceptable to make this movie. And he made it on a shoestring budget. It still made almost no money when it came out, but it was a critical success and that let him make another movie.

Ben Cohen: And so for a second movie, he makes another movie that nobody wants him to make. And for his third movie, he makes another movie that nobody wants him to make. But as he is doing this, he continues to be a hit with the critics, but he also starts to become a hit at the box office. And that’s a really powerful combination and it allows him to make a fourth movie that nobody wants him to make. And he sort of understands this. He has this conversation with a studio executive around this time when the studio executive says, “We want to be in the Rob Reiner business,” essentially. “Tell us what movie you want to make next and we’ll help you make it.” And Reiner says, “I’m telling you, you don’t want to make the movie I want to make.” And she says, “No, really, we do. Tell us what movie it is and we’ll help you make it.”

Ben Cohen: And he says, “No, I’m really telling you, you’re not going to want to do it.” And finally she puts an end to this Abbott and Costello routine that they have going, and she says, “Just name the movie.” And he says, “The movie I want to make is the Princess Bride.” And the studio executive says, “Anything but the Princess Bride.” And it was because there was … the Princess Bride was this mystery haunted by a riddle and a curse. Everybody in Hollywood had tried to make it. Everybody had failed. And yet Rob Reiner, because he was hot, because there were opportunities available to him that wouldn’t have been otherwise, he took advantage and he used his hot hand to make a movie that nobody wanted him to make. And it was a brilliant decision because it turns out that the Princess Bride would become this cult classic and one of the most beloved movies ever made. And so I think there are some similarities to a Dan Brown phenomenon there, where you can turn one hit and two hits and three hits into something else entirely. You can actually use it to change your entire career.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Right. And of course there are authors who arguably might be better writers than Dan Brown who didn’t happen to have lightning strike once, and as a result, their whole body of work never really got the same level of recognition.

Ben Cohen: Are you talking about me, Roger?

Roger Dooley: No, actually, your book isn’t out yet as we’re speaking. So I’m really anticipating that pretty soon you’ll be right up there with Dan Brown and in fact that way you can serve as real life proof of your theories. And do you have some other projects in the works?

Ben Cohen: Yeah, I’m working on this novel about people looking for DaVinci works in the Louvre. It’s this mystery thing. I think it has a real future.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well hey, Hollywood has proven that a formulaic ideas can still achieve success. So I would not discourage you from that.

Ben Cohen: Yes. If Tom Hanks is reading the Hot Hand, he can feel free to auction it whenever he wants.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’m sure he is among our listeners, so we’ll hopefully get some lightning striking there for you, Ben. So Ben, one of the anecdotes in the book that I found pretty funny involved Steve Jobs, one of our perennial favorites on the show because he’s exemplified so many things, but it has to do with randomness and music. Why don’t you explain that story?

Ben Cohen: Yeah, it’s a story about Spotify and it’s also a story about Apple because it turns out they sort of faced the same problems. Spotify, when they launched and they had something called a shuffle button, which was supposed to essentially randomize your music. And Apple the same way, they had a randomizer on the iPod. And what Spotify had to do was actually something that Steve Jobs had to do many years earlier. The problem here was fundamentally a reflection of how we systematically misread randomness and we see patterns where they don’t exist because it’s hard for us to understand randomness. We’ve actually sort of evolved to search for patterns. Amos Tversky, I mentioned him, again, once said, “We invent causes to explain those patterns.” And the pattern that Spotify and Apple users seemed to be hearing was that we would hear the same artists twice in a row on a playlist, sometimes even the same song twice in a row.

Ben Cohen: Now when you think about it, of course you would. That’s how pure randomness works, right? If you have a 10 song playlist, the chances are pretty good that you’re going to hear the same song twice in a row. But that’s not how we want randomness to work. It’s not how we want to listen to music. And so what Spotify had to do, which is what Apple had to do many years earlier, was actually changed their algorithms and disperse artists and songs evenly over the course of a playlist. Now this is kind of absurd, right? If you actually go back and watch Steve Jobs, his keynote speech, when he’s talking about this change that they’ve made to the iPod, he’s kind of laughing at the whole thing because what they really had to do was they had to make it less random to feel more random.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. So how did they do that?

Ben Cohen: They changed the algorithm. They literally went into the code and they gave us what they wanted. So instead of our playlists being purely random, they are random in the way that we think about randomness. So if you have a playlist of 10 songs, some by the Beatles say, and some by Beyonce and some by Billy Joel, they will make sure that you don’t hear Beyonce twice in a row, or, god forbid, Billy Joel three times in a row or four times in a row. They will space those songs evenly over the course of a playlist so that we get randomness the way that we think about randomness.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it seems kind of ironic that to please the brains of human listeners, we have to reduce the randomness to make it seem more random.

Ben Cohen: Not only were people convinced that the shuffle button on Spotify was broken, they were actually convinced that there were corrupt motivations behind this, like Billy Joel was paying Spotify under the table to keep playing him instead of the Beatles or Beyonce. I mean, it sort of speaks to why the hot hand has endured for so many years because it makes us crazy. We love thinking about it and even if we don’t always think about it rationally, it persists.

Roger Dooley: And of course our brains always trying to try to find a narrative for something that is … there may not be an obvious explanation for it, but our brains will try and create an explanation for that, whether it’s Billy Joel paying off Spotify or whatever it’s … there’s got to be a story there to make it make sense.

Ben Cohen: Right. Or Steph Curry is hot. Right. And that’s what the original paper said, is that we invented these causes to explain what is essentially randomness. And that’s sort of the core question that all of this, did we or did we not?

Roger Dooley: So Ben, we’ve discussed your fictional aspirations. I’m curious, in your work as a journalist, do you and your colleagues get measured by views or shares that articles get? And if so, and if people are tracking this stuff, do you see evidence of the hot hand there?

Ben Cohen: Oh, that’s an interesting question. I hadn’t thought about that. We don’t. We will not get like promoted or fired based on how well our stories are performing. However, we do have access to that data and we want our stories to perform well because we want those stories to be widely read because we’re proud of them. So I don’t think that I have necessarily found a hot hand effect in stories doing well because previous or future stories … I don’t think I’ve seen a hot hand effect of stories doing well because previous stories have done well. However, what I have felt at work sometimes is that I am in some sort of zone. And so sometimes that’s just on individual stories or coverage of a breaking news event where I will work harder in those weeks when I’m covering that story because I’ve put out a string of hits stories in a row and suddenly there are resources available to me that weren’t there when I started reporting.

Ben Cohen: People are reading those stories and they want to talk to me, which isn’t always the case. And so I sort of do feel this obligation, especially since writing this book, to kind of recognize when circumstance is bending my way and to try to take advantage. Because what I’ve learned while thinking about the hot hand, and also from my own experience with the hot hand on a basketball court many years ago, is that that feeling disappears. It doesn’t last forever. And it’s important to take advantage when it is there because you never know when it’s going to come back.

Roger Dooley: Well that is probably a good message to end on. Let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Ben Cohen, sports reporter for the Wall Street journal and author of the new book, the Hot Hand, the mystery and science of streaks. Ben, where can people find you and your ideas?

Ben Cohen: They can find me on Twitter or on my website, bzcohen.com. That’s B as in boy, Z as in zebra, Cohen. And I’m also on Twitter and every other social media platform. And read me in the Wall Street Journal. I write about basketball and other sports and other things sometimes. So in addition to this book, you can read me in the Wall Street Journal

Roger Dooley: If you are a subscriber, they have a very effective paywall I’ve found, but I have subscribed at times. So yeah, we will link to those places and to any other resources that we mentioned on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. Ben, thanks for being on the show.

Ben Cohen: Thanks so much, Roger.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.