Would you trust a doctor who didn’t understand physiology? An engineer with no knowledge of physics? Given how obvious those answers seem, it’s surprising that so many companies trust marketers who don’t consider behavioral science.

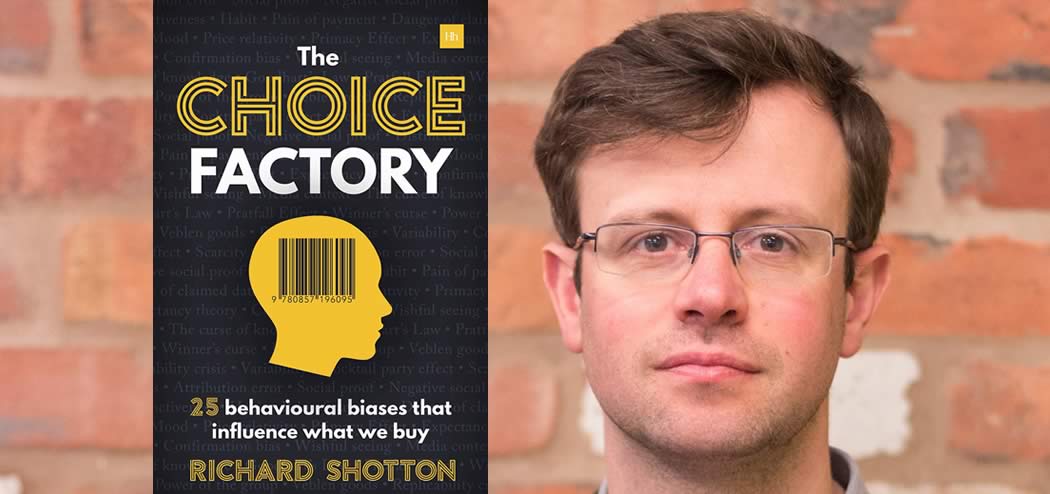

Today’s guest, Richard Shotton, illustrated the absurdity of this fact with the above comparisons in his book, The Choice Factory, and he certainly has plenty of room to speak on the subject. After starting his career 17 years ago as a media planner and working on accounts such as Coke, 118 118, and comparethemarket.com, he now studies how findings from behavioral science can be applied to advertising.

Richard currently serves as Deputy Head of Evidence at Manning Gottlieb OMD, the most awarded media agency in the history of the IPA Effectiveness Awards, and he writes about the behavioral experiments he runs for titles such as Marketing Week Campaign, Admap and The Huffington Post. He joins us in this episode to share his findings, how he has used them to increase campaign effectiveness, and more.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- What cognitive biases are, and how they affect our decision-making.

- Why so many advertisements don’t work.

- How Richard used the bystander effect to get more people to donate blood.

- A simple and effective tactic anyone can use to test a concept.

- The surprising social media strategy that increased Richard’s follower engagement.

- How to frame non-favorable social proof to make it sound positive.

Key Resources for Richard Shotton:

-

- Connect with Richard Shotton: Twitter

- Amazon: The Choice Factory: 25 behavioral biases that influence what we buy

- 67 Ways to Increase Conversion with Cognitive Biases

- Gumroad

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Believe it or not, this is episode number 200 and we’ve got a guest today whose interests align very well with my own. Richard Shotton has one of the more interesting titles I’ve run across. He’s Deputy Head of Evidence at Manning Gottlieb OMD in London. His particular interest is in how psychology and behavioral science can be applied to marketing. Sound familiar?

His new book is The Choice Factory: 25 Behavioral Biases That Influence What We Buy. I’m going to do something that I haven’t done once in the preceding 199 episodes: I’m going to read a very short excerpt from Richard’s book. Don’t worry; it’s really short. In the introduction he writes, “In the same way you wouldn’t trust a doctor with no knowledge of physiology or mention you’re ignorant of physics, my experience over the last dozen or so years suggests that it’s foolhardy to work with an advertiser who knows nothing of behavioral science.”

Now to me, that’s a perfect explanation of why so much advertising doesn’t work. Too many practitioners are either unaware of behavioral science or ignore its insights. On that note, welcome to the show, Richard.

Richard Shotton: Hi. Good to be here, Roger.

Roger Dooley: So Richard, what does a Deputy Director of Evidence do?

Richard Shotton: Manning Gottlieb quite an interesting setup where rather than, like a lot of other agencies have a disparate team of researchers, so the econometricians and the insight guys and the martech guys all spread across the agency, we’re all in one department. So we’re meant to be working much closer together than you might find elsewhere. My interest particularly within that is, as you mentioned, applying social psychology, behavioral science to any of the challenges our clients have.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative), and so by evidence I assume that means that a key part of what you’re doing is to actually test assumptions and see if they work.

Richard Shotton: Yeah, absolutely. There’s two reasons why behavioral science is of such interest, in that on one hand, you’ve already got this great body of evidence that’s based on some of the leading scientists’ work around the world, so you don’t have to start afresh. You’ve got some certain findings about human behavior, but perhaps better than that, you don’t have to take anyone’s word for it. The methodology of lots of experiments by Kahneman or Tversky or Cialdini, all openly available, and you can test those to make sure they work at this particular time in this particular country on this particular brand.

Roger Dooley: Right. That’s really a great message, Richard. It’s one that I’ve certainly been promoting for a while: that there’s this huge body of work out there that is scientifically robust, in most cases at least. We do have that replication crisis that’s … have to be a little bit careful, but by and large the work is very robust, and it’s such a great starting point for testing. It doesn’t mean that everything that worked in a laboratory in Berkeley or MIT or someplace else is going to work for your company’s advertisement, but it’s certainly a logical starting point. Some of these in particular, like social proof for example, that’s one of the topics in your book, it doesn’t always work but boy, probably 95% of the time, it does, based on my conversations with conversion experts. Every now and then, it doesn’t, but this wealth of knowledge is a great starting point.

Richard Shotton: When you work with a brand, your ideal is to sell more of their product rather than find an absolute truth. Often we say to people, “Well but there is this evidence, and you’ve got to test it for yourself, but at least you’re starting from a … you’re stacking the odds in your favor rather than just starting randomly each time.” What’s interesting in the point that you make is that there are occasions when things like social proof don’t work. What’s really interesting is that I think researchers now are finding out more and more about the exceptions to the rule.

There’s two examples I mention in the book. The first is a lovely experiment done by the Behavioral Insights Team, sometimes better known as the Nudge Unit. David Halpern talks about a case where they’ve got a very famous social proof study where they told people to pay tax on time because eight out of 10 people do so. That had an uplift of about 15% across the board, but there are a couple of groups where it actually had a negative effect, so the top 5% of debtors, the top 1% of debtors, when they were shown social proof message, it actually reduced their likelihood of paying their tax. Halpern hypothesizes that maybe these are very rich people. They’ve got businesses, done very well for themselves and maybe they almost define themselves in opposition to people.

In future tests, the Behavioral Insight Team worked on segmenting their messages, so they had different message for that very affluent group.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that’s interesting. I think that’s certainly one hypothesis, or maybe they just … Some people are happy to find out that everybody else is supporting the government so that they don’t have to. So Richard, I have to compliment you on your social media efforts. I think I stumbled across you because you tweeted a quote from my book Brainfluence, and unlike every social media handbook that tells you that if you’re going to do a quote from somebody, you should make a little work of art out orf it using something like Pablo or Canva, they’ll let you put a quote with a nice background and then use it, Instagram and Pinterest and Twitter and whatnot, basically you just take a photo of the relevant part of the book page and got the page curvature from the book in there and any maybe marginal notes or underlines included. You seemed to get a lot of engagement on those posts. Why do you think that’s effective? Is this an intentional nudge or just the easiest way to do it?

Richard Shotton: I stumbled onto it, actually. When I first started on Twitter, and I joined in 2008 but never really found it very useful. It took me quite a few years to really start using it heavily. I used to tweet links to articles with a little synopsis, and got a little bit of engagement. Then I think for one reason or another just decided to take a photo one day of a little snippet from a book, and it got much better engagement. Then I started doing that forevermore. I think about 90% of my … that’s really an exaggeration. About half my tweets probably are now just pictures of little snippets from a book. Always about advertising or psychology. I think the reason they are more appealing than a link is, it’s just that little bit easier for people to … they don’t have to click on anything. They can see whether they’re interested or not and read it. It’s just removed one little barrier and it’s had a significant increase in the level of interaction. Which I’m guessing is a behavioral point there.

Roger Dooley: I think probably it lends a little bit of authenticity, too. I mean, it looks like, “Hey, I was reading this book and found this cool thing I’m going to share with you,” as opposed to the more artfully done pull quotes where, you know, it looks like something that’s been sort of created to create social media content. I’ve done it once or twice myself, and based on what I’ve observed from your tweets I may adopt that too. In fact, maybe after people hear this podcast there will be a whole trend going.

Richard Shotton: Excellent. I wonder if there’s, I’ve never really thought about it before, but I wonder if there’s a bit of: if you artfully create something using some of those apps that you mentioned, if you create a lovely background, maybe some people are put off by that background and don’t want to share the statement, because they feel that the background doesn’t represent them, whereas if you keep it very neutral, which a photo of a book is, then perhaps it’s just available for more people to feel like they can retweet it.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I don’t know. Maybe you can do a study on that sometime. Richard, your book focuses on 25 cognitive biases. On my neuro marketing blog, we’ve got a massive post by my friend Jeremy Smith who describes 67 different cognitive biases. Nowhere near the detail, of course, that you do in the book. I’ll put a link to that blog post in the show notes page, but I’ve seen some lists that run to over 100 cognitive biases. For starters, why don’t you explain how you define cognitive bias?

Richard Shotton: Define it as a rule of thumb that people use to make decisions quicker in the world today and perhaps always, because there’s just too much information or decisions for us to weigh up what we’re going to do logically; to fully rationalize every element. Instead, we rely on rules of thumb that act as efficient, quick ways of making quite good decisions. Now, what’s of interest to marketeers is that those quick rules of thumb are often prey to biases. We can make our communications much more effective if we work with human nature rather than against it.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think the key point there is that many of these decision-making shortcuts that we use actually work in opposition to logic, so that, on like someone like Kahneman’s famous for expressing the exact same situation as a loss can produce very different results statistically than a numerically identical situation expressed as a gain. There’s no logical reason why that would be true, and I think for years certainly economists thought that people behaved mostly logically, but there’s such a huge body of evidence now that there’s all these effects that are sometimes subtle, sometimes not so subtle.

Richard Shotton: Yeah, because it’s interesting. You say that sometimes they aren’t logical. I mean, you could argue, maybe not on that framing example. Something like social proof, you could argue from a evolutionary perspective this was a really sensible, normally quite right decision-making approach, in that if everyone in your tribe or group sprinted in reaction to something, it would be in your best interests not to weigh up the situation but to just follow what everyone else did. There is often a reason, whether it’s logical or not. There’s a reason why the biases exist.

Roger Dooley: Right. I agree. Not all of them are contrary to logic, and if you look at some other Cialdini principles like authority, the same thing. There’s actually some good logic in following the advice of an authority, because presumably that authority knows what they’re talking about in whatever area they’re in.

Richard Shotton: Well yes, so the issue is sometimes those … certainly our environment’s changed, so what may have worked in one situation on the African savannas is not necessarily suited to a hectic, frantic 21st century life. You know, maybe moving outside of cognitive biases the most obvious thing is in diet. Our love of sugars and fats is a brilliant tactic over human history, but probably less appropriate in 2017.

Roger Dooley: Right, when sugar and fat are widely available at low cost. So, you’re in the ad industry, Richard. Explain something to me: it’s been decades since Robert Cialdini wrote Influence. That book sold millions of copies. We’ve had two Nobel prizes or more, depending on how you count behavioral scientists. Why do so many advertisers not get the message? Do you think more are now?

Richard Shotton: I certainly think more advertisers are using it, but I agree with your underlying point: that it’s still surprising how few are, considering how relevant social psychology or behavioral science is to advertising. Every day, advertisers are trying to change the decisions of consumers. They’re trying to get them to pay more, to switch less often, to pay out a premium. You’ve got this body of evidence that gives you the best way of doing that. A science of decision making. So it is surprising why it is not used enough. I think some of that might be to do with, you know, going all the way back to the 50s when Vance Packard’s Hidden Persuaders came out. That was a tarnished psychology, certainly, in America and Britain for a long time.

I also think there’s a over-reliance on asking people, so a lot of the time I think some of the biases that aren’t used is that marketers still insist on going and saying to consumers, “Well, why did you do what you did?” Unfortunately, one of the things we know from social psychology is that consumers aren’t necessarily … people aren’t the best. Don’t always know why they did the things they did.

Roger Dooley: That’s certainly true in some categories that are subjective like fragrance or something, but even in B to B I’ve seen surveys that are just totally inaccurate, and one I recall fairly early in my business career, there was a survey of these B to B buyers and they were asked to rate what was most important in selecting a supplier. The product was a commodity product with relatively minor differentiations between suppliers. They listed things like customer service and product quality and all these things, and price came in at like, number six or number seven. This was proof that the ad agency had been looking for that price didn’t matter if we excelled in these other areas. A small difference in price, obviously, not a big one, wouldn’t matter. When the company acted on that bad advice, where the people who were familiar with the industry said, “No, no, don’t do that!”, the business for that division dropped by literally 50% in a month, after a two or 3% price increase.

There the buyers who were surveyed weren’t trying to be misleading, but the industry was basically everybody charged the same price, because it was a commodity and you competed based on service. So for them, price was not a factor in their decisions because it never had been. But boy, once somebody was different, that shot to the top.

Richard Shotton: Absolutely. Whereas actually, I think that’s often the best thing to do is rather than listen to those claims, try and observe their behavior. Set up simple field experiments to observe people, and you can do that face to face, in the street, in various different settings. You can do it online. Ideally, I mention a few in the book, you can try and find a company bar or a pub or a coffee shop that you can work with to test ideas. There’s all sorts of ways now to look at behavior rather than just listen to clients.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think between the sort of experiment that you’re talking about and also the ease of testing digital stuff online now where you can do AB tests basically at no cost, assuming you’ve got at least a little bit of traffic going, makes testing so much easier.

So Richard, your first experience in testing a psychology intervention in advertising had to do with getting people to donate more blood. Why don’t you explain that?

Richard Shotton: It was probably, what, 2004, 2005? I was working with the NHS and one of the campaigns around give blood. I read the story about the Kitty Genovese murders in New York in 1964, and so for listeners that aren’t aware of that, it was a cause celebre at the time. A lady coming home from working at a bar, late late one evening, went home and unfortunately was brutally attacked at three o’clock in the morning by a serial killer called Winston Moseley. Now, this caused an outrage in New York because supposedly, according to the front page of the New York Times, it was witnessed by 38 people yet no one helped. No one intervened.

Now, all the editorial at the time was up in arms, because they were saying, “Well, how could this happen? Has society gone to the dogs? It was shocking that no one helped despite there being 38 people.” Two psychologists, Latané and Darley, were aware of the same case but thought the newspapers had got things the wrong way around, and that actually, people hadn’t helped because there were so many. They argued that there was a diffusion of responsibility. Over the next few years they ran a load of experiments which essentially showed the more people that you ask for help, the less likely any one of those is going to help.

I read about this, thought this was fascinating. Thought, well, bloody hell, this is exactly the same problem we’ve trying to deal with in advertising for this client. That we’re going out and saying, “We need blood from everyone in the country because our stocks are low.” Actually, wouldn’t it be far better if we regionalized, tailored, localized our appeals? So rather than going out and saying, “Blood stocks are low in Britain,” we’d go and say in Birmingham, “Blood stocks are low in Birmingham.” In Basildon, “Blood stocks are low in Basildon.”

Now, very luckily, there wasn’t really necessarily the place to suggest these things. Very luckily we were working with an amazing creative agency called DLKW and a lovely man called Charlie Snow. He liked that idea, persuaded the creatives to test it and a couple of weeks later, results came back in and customer response had improved by 10%. It was, for me, absolutely eye-opening that I’d been all these years in advertising and not realized there was this huge body of work that could explain why people behaved the way they did and best of all, it was very practical. It wasn’t some abstract science; you could just take it, try and apply the right bias to your campaign and generally see a positive improvement.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative), and that led to a lot more work and to this book, too. That’s great. That same sort of local, regional effect can apply in social proof as well. Generally, social proof is more effective if you can make the people involved in social proof more like the person who’s seeing it, so that’s some of Cialdini’s work and I think also the tax work in the UK, that when they were able to localize the tax payers in this specific city are complying at a rate of 80%, it was more effective than just saying “Taxpayers comply.”

Richard Shotton: Absolutely. Yes. I guess it was lucky that I stumbled across how bias actually works, otherwise my career would have…

Roger Dooley: Right. Had it been a failure, who knows? We’d be doing something totally different today. Getting back to social proof, talking about some of the classic examples, so Cialdini’s hotel towel experiments where the most effective messages were the ones that used social proof. That other guests are recycling their towels, and so on. Today it’s pretty hard to go to a website that doesn’t use some kind of social proof like, you know, how many customers they have, how many subscribers or some other indicator. But those are kind of interesting and when you talk about some of the potential applications of this, it doesn’t always have to be that “We have X number,” or, “X% of the people do this.” That just something visible like Apple’s white earbuds serve as a form of social proof. Why don’t you explain that? I thought that was interesting and I think it probably might guide the way for some brands to approach social proof in a different way.

Richard Shotton: Yeah. I think it might be … There’s a wonderful creative director called Dave Trott who was very prolific in the UK in the 70s, 80s and 90s. I think he pointed out this case to me first of all, the argument being that, yes there’s lots and lots of social proof done very directly, as you say. “1 million people buy this product,” or “eight out of 10 cats prefer this.” However, the Apple is a lovely example of a brand obliquely implying it was a market leader, maybe before it actually was.

In about 2001 when the iPod launched, pretty much every mp3 player had these bland, black earphones. Because people were keeping their mp3 in their pocket, you had no idea who was listening to what. Then on bursts onto the scene Apple in 2001 with these very distinctive white earphones, which everyone could see it was Apple being worn. It felt like it was a far bigger player than it actually probably was. So it implied it was popular, and then that became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

There’s a few nice examples of that I think I came across while researching the book. One that I read about that Jeremy Bullmore mentions was an old Ford ad, where they wanted to talk about the popularity of their convertible. Rather than being slightly crass and direct and saying, “We’ve sold a million convertibles,” or, “The most popular convertible in America,” instead they had a picture of a pram with a line above it saying, “The only convertible that outsells us.” There has been a history, I think, of clever, witty examples of social proof being applied.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and that’s a good argument, I think, too. If you have a brand that people would expose on their clothing or someplace else, to incorporate that because not only doing your job of advertising for you, but they’re giving you that social proof. Obviously that doesn’t work quite as well for luxury brands, because luxury brands don’t necessary want people to think that, “Gee, everybody’s doing it.” But for more mass-market like maybe athletic wear or something, then pretty effective. And of course, if you can do something that’s distinctive that isn’t a brand, that’s even better. If you can sort of make that link the way Apple did. Although coming up with that particular kind of strategy wouldn’t necessarily be easy.

Richard Shotton: No, absolutely. It’s easy in retrospect to see it as an obvious decision, but at the time, it would have been, you know… hugely.

One other thing that we looked at, I think I did a study with a lady called Claire Linford and we looked at whether or not people know brands are market leaders. Although you say lots of websites put their popularity, if you look at ads on the newspapers, magazines or TV, yes it’s not a completely rare tactic but it’s still … I think I went through some newspapers one weekend and it was only about one or 2% of ads that use social proof in the national press. I was wondering if one reason maybe social proof isn’t used more often is that people who work on brands, let’s say you work on a toilet paper, you’re completely immersed in this brand. You think about it 40 hours a week. You assume because you pore over the Nielsen reports that everyone in the world knows you’ve got this amazing selling toilet paper.

But when we surveyed 1000-odd consumers, for most of the … No, in fact I think for all the categories we looked at, more than half the people were unaware of the market leader and in lager in particular in the UK, only 24, 25% of people knew that Carling was the bestseller. Often what marketers think is an obvious thing that doesn’t need telling isn’t known to consumers.

Roger Dooley: Hm, interesting. I hadn’t thought about that aspect of it, but that makes a lot of sense. Something we’ve both written about, Richard, is negative social proof. A while back I described a pastor who tried to raise money by pointing out that 80% of the parishioners in the church didn’t contribute, and I think we both have commented on Wikipedia’s appeals about how only 3% of their users donate money. You know, it’s basically telling non-donors, non-contributors, that their behavior is completely normal and they’re fine.

If you have a situation from where your social proof isn’t strong, in fact sort of goes the other way like say like, “Yeah, I don’t really want to show these statistics.” Are there some ways that you can turn that around or use some different social proof that may not be quite as obviously to get that effect?

Richard Shotton: I think so. One of the very first examples you mentioned was around framing, and the same thing can be done with some of those stats. So you know, you mentioned the Wikipedia example. Only 3% donate. Wikipedia could honestly say something along these lines of, “10,000 people donate every single week.” Or they could survey people and ask them something along the lines of, “Do you think people who use our site should pay for it in some form?” And I’m sure you’d have 90-odd percent of people agreeing with it. So those are the stats that I would be publicizing. They’re not misleading; they are genuinely true facts, but they avoid emphasizing the small proportion. Instead they emphasize the absolute amount or people’s aims and beliefs.

It’s an interesting thing you bring up. I think Cialdini calls it “The Big Mistake,” and it does happen a remarkable amount of times. The Guardian are running ads at the moment which emphasize how few people donate. It is one that you see used worryingly regularly.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, hopefully among both of our readers and listeners, they’ve learned that lesson by now. But always good to emphasize it. Yeah, Richard, you know, years ago Sears was the biggest direct marketer on the planet and just about all of their prices ended in 97 cents, so an item wouldn’t be $10; it’d be $9.97. Does that still work?

Richard Shotton: Yes. I think that’s a fascinating one. You mentioned at the beginning, like, “Why aren’t more people applying psychology?” One of the things I forgot to mention was I think in advertising and marketing we’re obsessed with the latest new thing. Because social psychology has been around for so long, sometimes that damns it in certain people’s eyes. It’s certainly the case with charm pricing or prices that end either in £99 or 97 cents as you said, because we have reams and reams of evidence from quite modern experiments that consumers are more likely to purchase when a good’s at, say, £4.99 rather than £5. I think one of the latest studies used real world data from Gumroad and showed much better conversion rates when prices ended in 99 cents rather than round prices.

What’s interesting though is that certainly in the UK, the use of charm pricing has declined over time. So back in the 80s there were studies showing about, from memory here, but about 50 to 60% of prices ended in 9. That has decreased quite significantly over time. I did a study using 1000-odd prices that are collated by The Grocer for various different supermarket items. We saw that there had been a significant drop in the usage of charm pricing, to the extent that one or two of the supermarkets we looked at hadn’t used a single charm price in the range of prices we looked at.

Roger Dooley: But nevertheless the data shows that it tends to work. Again, that’s something that would be easy enough to test, especially on a eCommerce site. You mentioned Gumroad. In case any of our listeners aren’t familiar with that, that’s an eCommerce site for downloads, correct?

Richard Shotton: An eCommerce site where I think you can … I’ve not used Gumroad. The way I’ve heard it described is you can buy and sell stuff. I’ve heard it described as a bit like eBay, but it might be worth someone checking.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’ve heard it used for more intangible goods, but I could be wrong about that. I haven’t used it either.

Richard Shotton: The other thing on that, Roger, though, is because they do get us thinking. As you say, it’s very easy to test whether or not charm prices have a positive effect on sales, so when we started suggesting this to various different brands, one of the bits of feedback we got was, “Ah but it conveys a poor quality image.” We thought, “Oh yeah, this might be the case.” So what I did with a colleague was go out onto the streets around London Bridge, and we stopped people and we told them that a new chocolate brand was coming to the UK. Would they like to try it? It was going to be 79p for a 50 gram bar and could they rate the taste on a scale of zero to 10. So we got lots of people who answered that. Then we went out the next day, exactly the same spiel, exactly the same chocolate, but we told people it was costing 80p for the same weight of bar. What we found was that there was no significant difference in the rating of the taste whether it was charged at a char price, 79p, or a rounded price, 80p.

Despite there being this myth, I think, in the industry that it conveys poor quality dues, I’ve never actually seen any evidence of that and the small scale study I did with a colleague suggested that it wasn’t the case.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative), and that really simple experiment reminds me of one more. I don’t want to use up too much of your time here but I’ll ask you one more question, Richard. You ran a test for a company that was planning on introducing a men’s clothing line. You know, I thought that was a really simple, relatively inexpensive … at least I hope it was inexpensive … test that, you know, really anybody could do to test a concept out pretty quickly or at least to get some opinions. Why don’t you tell us about that one?

Richard Shotton: Yeah. A clothes wear brand that was associated with, they had always sold women’s clothes and they were launching a menswear range. Called New Look. What we did was we wanted to see whether or not men would be willing to shop there. Our hypothesis was that they would be put off by its female image. Now, we didn’t have any money to test this, so we needed to think a bit laterally. We couldn’t do various focus groups or chat to people or any other complicated study. What we did instead was colleague Dylan Griffiths and I took 12 male volunteers from around the agency, took photos of them one time holding a plastic bag emblazoned with the New Look logo, the one they used in their stores, and then the next time we did exactly the same thing but this time the people were holding a Topman bag. So the main competitor.

We put those photos up onto a dating site that was called Hot or Not. I think it became Badoo a couple of years later. The specialty of that dating site was that when you uploaded your photo, all the users would rate how good looking you were on a scale of zero to 10. So we left photos, one with the New Look bag, the other exactly the same pose with the Topman bag. We came back two weeks later, hundreds of different ratings and scores, and we saw that on average when people had the New Look bags, this brand was associated with women’s clothes, they were seen as 20, 25% less sexy than when they had the Topman bag.

So as you say, it was a really simple, really easy experiment that used the web almost as a laboratory. Tried to create a realistic situation. We didn’t quite do it for free. I think the aim was to spend nothing but we didn’t have any New Look bags so we had to go to the shop and buy a t-shirt. So it cost about a fiver to do that experiment.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and that’s such a great experiment and it really … There’s a couple of findings. First of all, it was important information for the brand, to know that theirs was not a particular powerful brand for men if it made them look less attractive, but also the influence of a small detail in a photo where logic might say, well, if you’re asked to evaluate a buy as far as how handsome he is, you’d look at his face, maybe his build and so on. You wouldn’t necessarily take into account some other details that aren’t really relevant to his appearance like a shopping bag or maybe even clothing itself, but obviously it had a big effect.

Richard Shotton: Absolutely. I think the outcome … With all these things there’s always a practical output, and I think the original belief of the brand had been, “Well, if we’re going to get people to shop at and buy our new range of men’s clothes, all we need to do is a simple announcement.” Our argument was, actually there’s a far deeper problem. You’ve either got to change the association of the brand so it’s seen as a unisex shop or you’ve got to make people comfortable with shopping at somewhere that’s associated with women’s clothes.

Roger Dooley: That there, that’s brilliant Richard. It’s a really cheap, almost zero cost study that leads to the need for a big expensive campaign.

Richard Shotton: In that case. I mean, it doesn’t … Not every thing … There is always a danger of you know, our study wouldn’t find that. But I think that has been, it’s certainly one of my favorite parts of the job: thinking, “Well, we’ve got a particular problem. How can we create a study to try and quickly and easily and reasonably low-cost prove the hypothesis one way or another, or prove a different hypothesis?”

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and you know, that totally dovetails. We had Om Marwah, who’s Walmart’s Head of Behavioral Science on this show, a few weeks ago, and that’s the same approach they take. Before they do any big expensive test or develop an app or something that would require a lot of investment, they’ll send one of their people into a store with a bunch of copy paper forms or something, just to get that sort of initial test and then depending on what they find there, then they can refine it, maybe scale up a little bit. But you know, rather than this whole thing of, “Let’s build it and then see how people like it,” it’s, “What can we do really cheaply that will tell us if we’re on the right track or not?”

So let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Richard Shotton, Deputy Head of Evidence at Manning Gottlieb OMD, and author of the new book, The Choice Factory: 25 Behavioral Biases That Influence What We Buy. Richard, how can people find you and your work online?

Richard Shotton: Well, as you mentioned right at the beginning, I’m quite a regular tweeter, so I tweet off the handle @rshotton. That’s probably the best way to find me. I’m normally tweeting about either social psychology or the interplay between social psychology and advertising.

Roger Dooley: Great, well we’ll link there and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. You’ll find a handy text version of our conversation there, too. Richard, thanks for being on the show and good luck with the new book.

Richard Shotton: Fantastic, thank you very much. Good to speak to you, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion, and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at rogerdooley.com.Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.