Being respected is a competitive advantage for brands, but being loved is the ultimate differentiator.

Have you ever thought about what brands in your life you can’t imagine living without? Maybe the thought of giving up your Apple computer gives you anxiety, or the idea of shopping anywhere other than Amazon makes you cringe. Those are the types of reactions that indicate how strongly we become attached to brands—if their marketing is done right. Even for very technical products, emotional ads can increase brand attachment.

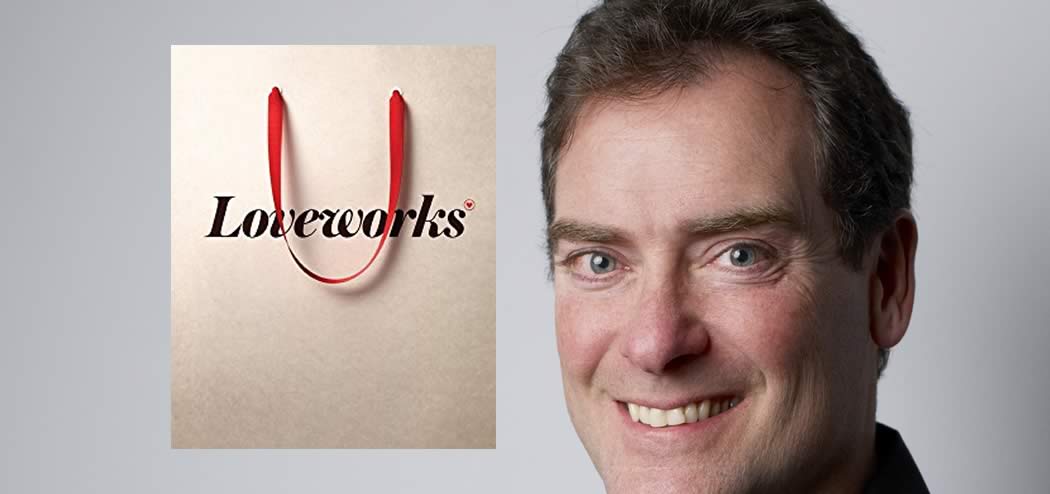

Today’s guest, Brian Sheehan, knows all about what it takes to create that kind of powerful brand attachment. During his 25 years working with Saatchi & Saatchi Advertising, Brian worked with top national and international brands, including Toyota, General Mills, Procter & Gamble, Hilton, IKEA, and many more. He has also consulted for a number of national and international companies, including Petrobras, Brazil’s national energy company, and Intesa Sanpaolo, Italy’s largest bank.

Now the Professor of Advertising at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, Brian teaches courses in advertising, advertising management, advertising strategy, digital advertising, and international advertising. His new book, Loveworks: How the World’s Best Marketers Make Emotional Connections to Win in the Marketplace shares his insights about successful marketing, and he joins us in this episode to explain what it takes to become a brand that consumers can’t live without.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The thing highly successful brands have in common.

- What many marketers keep getting wrong.

- Which question determines if a consumer “loves” a product.

- Why it’s easier for small brands to engender “love.”

- The unique advertising language that transformed T-Mobile’s brand.

- Four key steps to becoming a “love” brand.

Key Resources for Brian Sheehan:

- Connect with Brian Sheehan: Email

- Amazon: Loveworks: How the World’s Best Marketers Make Emotional Connections to Win in the Marketplace

- Kindle: Loveworks: How the World’s Best Marketers Make Emotional Connections to Win in the Marketplace

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is Brian Sheehan. Brian is a Professor of Advertising at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Communications. He’s a 25 year veteran of Saatchi and Saatchi, and has held key positions in New York, Hong Kong, London, Australia and Los Angeles with that firm. His articles appear in Ad Age and Adweek, and he’s the author of Loveworks: How the World’s Top Marketers Make Emotional Connections to Win in the Marketplace. Welcome to the show, Brian.

Brian Sheehan: Hello, thank you. It’s great to be here.

Roger Dooley: We’re experiencing some pretty chilly weather here in Texas over the last couple of days, Brian. We’ve had a hard freeze that’s probably lasted about 36 hours, which, for Austin, is very unusual. But, I’ve got to believe it’s even chillier in Syracuse, New York. What’s it like there?

Brian Sheehan: Yes, well, welcome to our world. It’s been probably an average of about five degrees all week. Today, it got up to 23, which is positively balmy, so we’re thrilled.

Roger Dooley: Right. And those are Fahrenheit temperatures, so those are all well below zero Celsius.

Brian Sheehan: Yes, absolutely. Tomorrow, it’s supposed to really get down maybe below zero again.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, better you than me. I grew up in Buffalo, New York, and spent years and years in South Bend, Indiana, so I’ve had enough of that cold stuff. But, stay warm.

Anyway, Brian, I’m sure that many of our listeners know that the Newhouse School at Syracuse is one of the pre-eminent schools for communications, particularly broadcast journalism. In the last decade or two, we’ve seen really dramatic changes in the media landscape: big TV networks are no longer dominant, local newspapers are either gone or fighting for their lives. Much of this change has been driven by the shift to digital. How has Newhouse adapted its focus to stay relevant and prepare its graduates for the future?

Brian Sheehan: Well, I would say I think we’ve done a really very good job of transitioning to the digital age. I’ll say that, but I will also say that our transition has been painful for all media. The internet has really disintermediated lots of marketplaces, not just the media marketplace, and it’s created a lot of change.

It’s really challenged us to look at our curriculum. We put a completely new curriculum in place around 2009, just as it was clear that digital was going to revolutionize the media landscape. We’ve continued to work with that, we’ve merged departments, I’ve also worked with a number of professors over the last year to create a group here called Navigate New Media, where we get together regularly to talk about what is happening, what are the dynamics of the change and how is it affecting all the different media that we look at as a school.

So, the answer is I think we’re doing a pretty good job, but that still puts us kind of behind, just because changes are happening probably faster than anyone can deal with them.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, I’m sure it’s going to keep changing, too. But, these days, I guess the barriers to entry in the field have really become far, far smaller, so I think it makes it all the more challenging for those schools that previously were sort of the gatekeepers for people in media now to maintain that position and also convince people that what they’re doing is valuable, which, of course, it is, because just the fact that anybody can publish a blog doesn’t mean that everybody is particularly good at it or is a journalist. So-

Brian Sheehan: Absolutely. We’ve had challenges here because some of the things that we’ve been famous for historically, for example, our journalism – we are one of the great journalism schools in the country – has really been challenged. It’s hard to make money in old fashion in journalism, if you will. The good old newspapers have pretty much folded up or at least had trouble monetizing news. Magazines are having some of the similar troubles.

So, a lot of our transition, we’ve had a lot more students coming into areas like public relations, like advertising, and continuing to come into television, film and radio. We’re still offering everything we’ve offered before, but we notice that students are realizing that some of them may lead to more lucrative positions in the future, so we’ve had more students moving from one department to the other, for example.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Of course, there’s always content creation and content marketing, which, again, that’s an area that may have few barriers to entry, but, for those folks who want quality and well trained people, that’s … Newhouse is probably … our very good source for that kind of graduate.

Brian Sheehan: Absolutely right. I’ll tell you, as an advertising professor, I’ve really never found the marketplace more exciting. When I started in the business in the 1980s, it was pretty much if you had a decent sized client, you were going to do a television commercial every year, you might do some print ads, you’d do some outdoor, you’d do some radio. Actually, most of the year was spent trying to figure out where you were going to run those things in media that was really five or six deep.

Now, it’s really exciting because commercials can be two minutes long, they can be eight minutes long, they can be six seconds long. All the things you can do online, all the content that you can create, is so interesting and dynamic and exciting. I think it opens up a lot of creative possibilities that didn’t exist 30 years ago.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Well, let’s move onto the book a little bit, Brian. I think the very first thing that the reader encounters opening the book is a full page graphic of a quote from Dale Carnegie: “When dealing with people, let us remember we are not dealing with creatures of logic, we’re dealing with creatures of emotion”. Then a few pages later, there’s a highlighted quote from neurologist, Donald Calne: “The essential difference between emotion and reason is that emotion leads to action, while reason leads to conclusions”.

I think our listeners would agree with both of these statements. Most of them I’d say are very well attuned to idea of non conscious drivers for decision making. But, the funny thing is that the Carnegie quote goes back many decades, and his book remains one of the most widely read books, even today. I just saw, on Amazon’s list of most read books, his book was on there, which is truly phenomenal.

But, with as much exposure as his thinking has gotten, and certainly many other folks, ranging from Daniel Kahneman and so on, why do marketers keep getting it wrong and do this logic stuff, they try and persuade people with logic?

Brian Sheehan: Well, I would laughingly say because marketers go to business school. I think, in reality, what marketers are taught to be are managers, and one of the key things managers are taught to do is to look for ways to take risk out of the system. They’re looking for ways to find something that works and repeat it, organizationally. That’s really why it’s funny, because you would say to yourself you’ve got all these really smart people in clients, why are there so many ad agencies in the world? Why, for example, can’t they just do their own advertising? They know more about their products than the agency ever will. They’re more deeply attuned to the organization and to how that product is made than the consumer or the agency.

The reality is they think too logically about the situation. At the end of the day, they’re selling to consumers, and, as you said, we’ve known for hundreds of years, perhaps thousands of years, that consumers have logic, but they don’t necessarily buy things based on logic. That’s why this book is really important in terms of looking at new research techniques, for example, to find out how people are reacting to products and what the opportunities are for different brands and different marketplaces.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. So, the book, Loveworks, is a follow on to an earlier book by Kevin Roberts, Lovemarks, and, actually, Kevin wrote the intro to this book. What is the story of Lovemarks? It’s turned into something that sort of grew beyond the initial book, right?

Brian Sheehan: Well, it did. It was interesting because when Kevin launched the book … Kevin was my boss, which is one of the reasons I wrote the follow up book. Kevin wrote this book, and it was really talking about the things we’ve already been talking about: that consumers are ultimately emotionally driven, and that if we can connect to them based on emotion, not only can we give them a better brand experience, but we can probably sell them more and sell them things at a higher price, which is ultimately what marketing is all about.

Kevin really dove into this idea that brands that succeed at the higher level are brands that tap into things like mystery, sensuality and intimacy. These are things that are not necessarily logically driven. They’re not necessarily saying, “Here’s a side-by-side scenario where we beat the other brand.”

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Right. Those are terms that you don’t hear thrown around that much in marketing discussions, at least in my experience.

Brian Sheehan: No. It was interesting because Kevin launched the book in 2004, and, at first, people made fun of it. Marketers would look at it and they’d say, “Oh, we’re going to talk about the ‘L’ word today,” and they were made very uncomfortable by the word ‘love’. What happened was it started to grow and people started to understand what this was about. Really, by the end of the 2000s, around 2010, it was hard to go to any boardroom in the country where people weren’t talking about either making their brand a lovemark, or something equivalent to that. Advertising Age, for example, named this book “one of the biggest ideas of the decade”, when six or seven years earlier, people were making fun of it and thinking it was all just a big joke.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, it wouldn’t be a business book, I guess, if it didn’t have an XY graph divided into four quadrants. As those things go, I think the one that you have in Loveworks really is rather sensible. It’s easy to understand and it seems to make sense, to me at least. Why don’t you explain the love and respect axis and the different quadrants?

Brian Sheehan: Sure. The love and respect axis, as we said, any axis, from north to south it’s respect, and from east to west it’s love. What you generally have is, on the bottom left, where you have low love and low respect, you pretty much just have a product. When we say a product, we’re talking about a commodity. It’s completely interchangeable. We don’t care what brand it comes from, it’s not something we care that much about, and we don’t respect one brand more than another.

As you move up into the top left hand side, we’ve got high respect and low love. We have what we would call brands, and those are brands where I respect and I believe that the performance of one brand might be better than another. That’s usually on a logical basis. That’s really what’s been happening in advertising for the last 100 years. The goal people have had is to build brands. Ultimately, by building those brands, people can look at the brand and say, “Okay, I trust that this brand will do something for me. I trust when I buy Tide, it will get my clothes clean. I don’t have to think beyond that. As I walk down a supermarket aisle, I don’t have to make lots of decisions about what I’m going to pull off the shelf.”

So, branding is a wonderful thing. It helps the consumer, and then those brands obviously are able to charge a few cents more, a few dimes more, sometimes a few dollars or even a few hundred dollars more, based on the fact that people respect them.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I think so Brian, I think that plays well into the sort of system one decision making that Kahneman talks about, where when there is a respected brand and you’ve purchased it before, you really don’t have to think about it. It can be done on autopilot, so you don’t have to devote cognitive resources to really evaluating all the detergents on the shelf, and there are a lot of them. There certainly is value in having a recognized and respected brand. But, go on.

Brian Sheehan: Well, there really is. And just as a side, because you brought it up, I actually have my students, every semester, they do a project, a case study, on the shampoo market. I ask them to go down the shampoo market, and their job is to create a new shampoo and to position it in a gap in the marketplace. It’s really funny because they’ve been walking down shampoo aisles their whole lives, but then when they walk down it and start thinking about how they would position a product, all of a sudden they realize, oh my God, there’s an entire aisle of shampoos and it’s five stories high and it has hundreds of brands.

To your point, if a consumer had to think about every apple juice that they bought and every shampoo that they bought and every detergent that they bought, they’d be in the supermarket for 10 hours. They’d walk out very stressed. So, brands really do allow you to just say, “Here’s something I trust. I put it in the cart and-”

Roger Dooley: Have your students been able to find those gaps in the shampoo market? As you were saying that, I was visualizing what the shampoo aisle looks like in my local supermarket, and there’s just so much there. It’s hard to visualize that there’s sort of a big empty spot, even an emotional spot, that somebody’s overlooked.

Brian Sheehan: Well, it’s funny you say that because, actually, they have. It’s not often. Usually, people come back with very similar things like a kid’s shampoo or a shampoo specifically for men or something, very niche things. One that I thought was really interesting was a seasonal shampoo, where they would go into certain markets, like the Northeast, and they would have a brand, but it would have a winter mix, a summer mix, a spring and a fall mix, because your hair is up against different elements. I thought that was very interesting.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Not sure how real or practical that is, but you’re right, it would stand out, and there would be probably some consumers who would say “Wow, this is great. I always think about my hair in the winter differently.” So, yeah, interesting.

Brian Sheehan: Just a thought. Going back to the matrix … Well, I’ll start going to the bottom right, which is where we have low respect and high love. That may sound great. People, they love you, but they have very little respect, and that’s what we call a fad. That’s something where everyone loves you for 10 minutes, you sell lots and lots of products, and a year later you’re out of business.

Roger Dooley: What would an example of that be?

Brian Sheehan: Oh, pretty much any fad in the marketplace. For example, Pokemon Go is a perfect example of that. Pokemon Go was this, we’ll call it a product, where everyone played, and it was the coolest thing in the world for a month. Now, trust me, there are very few people in the world playing Pokemon Go.

The key area that we’re looking at is the top right, where we can have high respect and high love. The great thing here is, when you have that, when consumers get up into the high respect, high love area, not only is the brand giving them a superior experience … So, where people really want to be is in the upper right, where we have high respect and high love. That’s really rarefied air. It’s a very hard place to be. It means that a brand needs to get consumers to love it. I think it’s important, when we use the word love, we don’t mean love like the way you love your wife or the way you love your daughter or the way you love your son, or even perhaps the way you love your dog. The research question that we ask to establish love is: is this a brand you could imagine living without? In reality, we can all live without any brand, but there are certain brands that are part of your daily life, that you would rather not live without. You couldn’t imagine living without them.

I have a group of students that I meet with, teach every fall, and it’s the only really big class that I teach. It’s about 80 students, and it’s done in an amphitheater. It’s funny because when I look out at them, what I can see that they can’t see, ’cause I’m looking at all of them at once, is I can see 80 glowing apples. They’ve all got their computer open, there are all these apples, right? Of the 80, it’s usually 80 of 80 or 79 of 80 are Apple users. What I do for a little bit of fun is I say to them, “I have to read a letter from the chancellor,” and I hold up a piece of paper with our University letterhead on it. I say that, “The university is becoming a PC only campus, driven by the needs of our business school. The bad news is we will no longer support or allow you to use Apple products on campus, the good news is we’re going to buy all of you a top-of-the-line Dell laptop computer.” Then all hell breaks loose.

Roger Dooley: I’d love to see that.

Brian Sheehan: It’s funny. The students are like, “You’re kidding?” I’m like, “No, I’m not kidding. This is what we’re doing as a university.” I’d say, “You can’t do that,” and I say, “Wait a minute. What’s the problem?” I literally have two or three students will say to me, “I’m sending an email to my parents and I’m going to look into transferring to a new school.” Now, the Newhouse School is a top school, it’s one of the hardest schools to get into in the country. Our students often have worked their whole lives to get here, yet what I just told them is I’m buying them a $1000 top-of-the-line laptop, and they’re leaving school. That’s how strongly they feel about their Apple products.

So, Apple, in that case, is a clear lovemark. I laugh because when I brought my daughter … My daughter went to college a few years ago, and I brought her to the mall, and we went and we bought her an Apple laptop. I knew that I was paying $200 – $300 more than the equivalent PC in terms of just pure computing power, yet I did it gladly, my daughter did it gladly, and all of the 80 students in my class did it gladly, and most of the students in the country do it gladly. Because they love the brand. It’s not a brand they can imagine living without.

That’s a really good demonstration of the difference between a lovemark and a brand. Dell is a brand, Hewlett Packard is a brand, they’re very well respected, but they don’t tap into the emotions the way a brand like Apple does.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. An example I’ve used a few times on the podcasts are … Listeners may get tired or hearing it, but, for me, I see something equivalent with Amazon, where I don’t really think about loving Amazon, but when I think about buying from somebody else, I sort of cringe.

We had a test here in Texas a few years ago, where, previously, they did not charge sales tax in Texas. Then, ultimately, they negotiated a deal where they’d build a couple of warehouses, but they began charging Texas sales tax, and suddenly … It was equivalent to an 8% price increase on basically everything that they sell. That’s not a small thing when you’re buying stuff, but I found that my buying behavior changed almost zero, despite … I did not anticipate … I thought before that I’m probably going to start shopping around a little bit more and so on, but, in fact, I didn’t because the Amazon experience was just so good, and I didn’t even want to try shopping with other folks.

Brian Sheehan: It’s interesting. Amazon has a couple of big advantages there. One, of course, is that it was really the first big online marketplace, meaning everyone was shopping with Amazon and felt comfortable doing it. Now I think we’re at a stage where, you know, how many different places do you want to open up an account with, who’s going to have your information and where you’re going to have a different password. Beyond that, I think the real thing that they’ve done to move to lovemark status is Amazon Prime. Prime is an amazing marketing product, and not only does it … Once you pay your money for Prime, it’s almost impossible to buy something anywhere but Amazon, because you think, oh my gosh, I’ve got this Prime and it’s all free shipping, I’ve got to buy everything there. Then, on top of that, you get Prime TV. It’s a miraculous product, it really is, and I think Amazon is clearly, among many people, a lovemark.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Let’s get to some of the examples in your book. I think that beer is a product that depends on emotional attachment. I agree that at least most American beers, traditional American beers, taste alike. Few people could differentiate them. So, it’s some kind of an emotional attachment to a brand or the brand values, and so on.

Now, we’ve got the craft beer movement today that’s sort of fragmenting things, but you tell a story of Guinness marketing their beer in Africa, which I thought was not just one, but a remarkable sequence of approaches to turning that brand from a well respected brand into a love brand. What did they do?

Brian Sheehan: Well, it’s interesting. They did something that a lot of the cases in the book do. They took a very different approach to research. We talked earlier about this idea of logic versus emotion, and many marketers lean on things like focus groups, one-on-one interviews, surveys, and even social listening, which is a little more honest, but it’s not exactly reflective of how people think and how people act in the real world. So, what they did, is they did something that Saatchi and Saatchi calls exploring, and it’s a type of ethnographic research. What it does, that I find really interesting, is often when we’re doing ethnography, where we’re getting involved in the lives of consumers, we still often have some research objectives that we want to meet or we have a discussion guide that we want to follow. What they did in the case of Guinness in Africa is they threw that out. They just said, “Look, we’re not going to have a discussion guide, we’re not going to have a questionnaire. What we’re going to do is we’re going to put on backpacks and sneakers, and we’re going to go out into the heartland of Africa, mainly countries like Nigeria, and we’re going to actually see what life is like and how people interact with our product and products like it.”

What they did is, when they went out, they found a couple of things. First, they found that outside of the big cities, there was a real dearth of entertainment. Many people didn’t have televisions, for example, and the pub might be a place where people would go and they could all watch TV together, while they were drinking the product. Also, at this time, this really happened about 10/15 years ago, when this campaign started, it’s about a 15 year campaign … what they found was there were really no black African role models for men. Men in Africa had a really bad image, in part due to things like the most famous African men were people who were warlords. There was a whole issue of child soldiers. And beyond the shining example of Nelson Mandela, there were very few black African role models, or even heroes in the movies or on television.

So, what Guinness did is they actually created a black African hero, and his name was Michael Powers. What his role was, he was kind of, you would say, an African James Bond, and he was always up against evil geniuses and he would always find a way to capture the evil genius, to get the girl, to get the beer, very much like a James Bond character. What was really interesting is that, as this campaign developed, he became one of the biggest heroes in Africa. It was really a new look, in Central Africa, to believe that there could be a black African hero, to the point where television stations started running the ads as a public service. When the actor who played Michael Powers would show up at airports in Central Africa, tens of thousands of people would be there to welcome him. It was all about the power that was inside African men and they called it ‘greatness’. The greatness of Africa, the greatness of Guinness and the greatness of African men.

The campaign ran like that for a few years and then it went and transitioned from Michael Power, who was sort of this made up superhero, to the goodness and greatness that’s in the average African man, the average African man who does what’s right for his family, who does what’s right for his tribe, who does what’s right for his community. They started running campaigns showing real African men doing small things that made a big difference in their communities. It was an incredibly successful campaign, and, in the end, Guinness became not only the best selling beer in Nigeria, Nigeria became the number one Guinness market in the world. They actually drink more Guinness now in Nigeria than they drink in Ireland.

Roger Dooley: Very powerful. How did they connect the brand to these things? Was it a pretty subtle branding effort in the commercials, whatever?

Brian Sheehan: It was. In part, the brand was very easy to connect because the product itself, which is, you know, it’s strong tasting, it’s a little bit bitter, and it’s black, it looks different than a lot of other beer, tied in very closely to a lot of tribal drinks that were drunk originally in Central Africa and that had the same sort of consistency. They were black, they were very strong flavored and they were bitter. So, they were already seeing … That sort of drink was already seen to hold a lot of masculinity in it. They really didn’t have to do a lot, they just had to own it, by the word ‘Guinness’ and the word ‘greatness’. Guinness was all about the greatness of Africa.

Guinness very much, if you go to Africa, is seen as, in many ways, the African beer, which is, in a way, silly because it’s obviously the Irish beer.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Of course. Let’s switch to a less likely brand for being loved, T-Mobile. In general, cellphone service providers are not loved at all, it seems like. Did they really become a loved brand?

Brian Sheehan: Yeah, they did. They did it because they created an advertising language that was different than everyone else. What they were trying to do is show off that they have 3G speeds, back then … Now we’ve got 4G speeds. They were really trying to underscore this idea that if you wanted to share things on your phone, there was no faster, better network to do it on than T-Mobile.

What they did, instead of just doing traditional ads, they actually created sharable events. They created really one of the very first flash mobs of all time in Liverpool Street Station, where, all of a sudden, in the middle of rush hour, a dance started, and all of Liverpool Street Station was crowded with dancers. People were on their phones, taking pictures of it. They followed that up with the world’s largest singalong, which they did right in the center of London. They got about 10,000 people, all singing. What they did, which was really interesting, is they brought in Pink, the recording star, Pink, who got up there, so it ended up becoming a free concert with Pink, and they had recording stars from all over Europe sprinkled throughout the crowd. They had people filming this, and they turned those into commercials for all different markets in Europe.

They did this and many other things, where they would create these live demonstrations, where hundreds of people, thousands of people, even tens of thousands of people, would capture it on their phones. That was really fun because it kind of showed that the brand got it. It’s not just about advertising, it’s about sharing. The tagline around all this was ‘Life is for sharing’. They were doing things in a very different way than other phone companies were.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I guess probably the most hated category of all are cable service providers, at least in the US. In fact, we got started a little bit late recording this because my cable internet service went out and I had to reboot the whole thing. Do you think you could turn Time Warner Cable into a lovemark?

Brian Sheehan: Well, that becomes a key question, right? Can you turn anything into a lovemark? The reality is I think you can turn almost any brand into a lovemark if the brand is willing to do what it takes to make that experience great for their consumers, not just on an advertising basis, but on a product basis. You have to be able to deliver. It’s funny, because if you look at airlines, for example, airlines, at least in the United States, are one of the most hated categories. Yet, you look at a brand like Southwest, and the love that it engenders, because that’s a brand that’s willing to do what it takes for its customers.

So, to answer your question, if that cable company’s willing to do what it takes, yes. If not, no.

Roger Dooley: Oh. Fair enough. All of the stories in the book are about big brands with relatively large budgets, some larger than others certainly. If a smaller business, if an entrepreneurial business or perhaps a local business wanted to employ this strategy, how would you suggest they go about doing that? Is it even possible to generate the same kind of thing, where you don’t have massive amounts of money for market research and sort of in depth studies and then, of course, enough to spend on media and so on?

Brian Sheehan: Yeah, actually I think it’s easier. In many ways, the reason I wrote the book is to prove that big brands can engender the kind of love that small brands find easy to engender. When you’re a small brand, for example, when you talk about doing research, you’re doing research usually amongst a smaller community, and the word ‘community’ is really important. When you’re a small brand, or at least a new brand, you’re usually coming to the marketplace ’cause you have a distinct point of difference. It’s very hard to come in as a small player just offering what everyone else offers, you’re not going to last very long. You’re usually offering a new proposition, or something different.

I actually think it’s much easier for small brands. And if I can, I’ll just talk about at the end of the last chapter, it talks about what big brands have to do to start making this transition. What it says is there are four key steps. The first step is discovery, which is discovering how the general public actually feels about your brand, as opposed to how you think it feels about your brand. Again, smaller brands that are tied in more closely to their communities find that easier to do. The exploration process, which is step number two, that research process. One of the reasons big brands have to employ ethnography is because they live in these buildings and they’re looking at lots of research reports. Smaller brands, newer brands, are actually much more attuned to their community, so, again, that’s easier. The whole creative process is easier, which is the third step. Then, finally, the fourth step is all about getting your community involved, allowing them to help you do your advertising, helping them to propagate your brand’s proposition.

So, that’s a long way of saying I actually think that if you’re a new brand, a small brand, and you’ve come into the market with a distinct point of difference, and you’ve done that because you actually get and understand the community better than the big brands do, all of this is much easier.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. That’s fair enough, I think. I think probably my favorite story, Brian, in the whole book was how Toyota reconnected with their rural Australian customers by ads featuring border crossings into the outback, and this was for their four wheel drive vehicles. This campaign ran years before Cialdini came up with his 7th Principle, Unity, but I think it exemplifies it perfectly. Toyota saw that these customers thought of themselves as sort of a unique tribe, and they built on that. You can explain some of the things they did in these ads and the border crossings, but, to me, I thought it was just a brilliant campaign, that apparently worked pretty well for them too.

Brian Sheehan: Oh, absolutely. This is one of my favorite campaigns too, because I was CEO of Saatchi Australia for three years, so my son was born in Australia, I love the country. What I love about it, also, is it’s a country with an incredible sense of humor. When you look at what they did is … Originally, this campaign was just meant for the outback. If you look at the Australian population, most of Australia’s population is in two big cities. It’s in Sydney and it’s in Melbourne. The rest of the population is really spread out. There are some other medium size cities: you’ve got Adelaide, you’ve got Darwin, you’ve got Perth. But, a lot of the outback, you know, you’ve got a country, which is physically the size of the United States, with about 10% of the population, and almost all of that population along the coasts.

So, when you look in places like Queensland or South Australia or Western Australia, these are people who see themselves as good, old fashioned Aussies. They’re Aussies who are really in touch with themselves, they’re not pretentious in any way, shape or form, and they live on the country and in the country. In many ways, they see the people in Melbourne and Sydney as being soft, right? These are people that have become city dwellers. So, the campaign was originally to really sort of appease those outback Australians and say, “Toyota’s making cars, this Landcruiser, for really tough people. It’s a really tough car for really tough people, and unless you’re driving a Landcruiser … We’re setting up these border crossings, so none of these metropolitan, soft, pretentious people can come in with their pretend four wheel drives.”

It’s a really, really funny campaign, and the best part of it was the people in Melbourne and Sydney, because they’re real Australians, can make fun of themselves too. They know that they’ve gotten soft. They kind of wish they were tougher and like real Australians. So, the campaign originally was just for the outback, but it became so popular, it started running in Sydney and Melbourne. It really helped Landcruiser become more of a lovemark. Landcruiser has always been a lovemark in Australia, but this campaign helped it become even more of one.

Roger Dooley: I thought it was great. The confiscating lattes and tofu and so on.

Brian Sheehan: And man bags.

Roger Dooley: Oh, man bags, yeah. Of course. It’s great stuff. Certainly, I can see how it would appeal both to the folks in the more rural areas, but at the same time, if you look at the four wheel drives that are sold today in the United States, certainly a lot of those are sold to people who are never going to take them off road, but they still want that rugged image.

Brian Sheehan: Exactly. It’s all about the imagery.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Are there any campaigns running today, Brian, that you think are really smart and would compare with some of the ones in the book?

Brian Sheehan: Oh, you know, I haven’t really thought about that. Let me think. What do I … You know, I have to admit, this is a funny campaign that’s one I’ve been doing a lot of research on, actually, is Bud Light. The Bud Light Dilly Dilly campaign is actually one of the most successful beer campaigns in the last 20 years. In many ways, it is because of its pure and utter silliness. The idea doesn’t mean … Dilly Dilly doesn’t actually mean anything, but it’s really captured the imagination of people. If you go online at any given time, you’ll hear people in social media using the term Dilly Dilly. So, consumers have co-opted this idea, and that’s really the best you can do. When you’re a brand and you want to be a lovemark, when consumers are co-opting your ideas and using them amongst themselves and with each other, that’s really an example of a brand that’s offering a much better experience to its consumers. That’s just one that jumps top of mind. I’m sure if I had more time to think of it, I could think of it.

Roger Dooley: That’s great. That’s probably a good time to wrap up, Brian. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Brian Sheehan, Advertising Professor at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School, long time Saatchi and Saatchi Executive and author of Loveworks. Brian, how can people find you and your stuff online?

Brian Sheehan: Well, they can contact me. I can give you my email address, which is bjsheeha – Sheehan without the last letter – @syr.edu. There’s also a video on YouTube about the book, which I believe I’ve given you a-

Roger Dooley: Right. We’ll link to that video in the show notes page, and we’ll also link to any other resources we talked about during our conversation.

Brian Sheehan: Sure. And then I’m on Twitter and I’m on Facebook and I’m on LinkedIn, just like everybody else. But, generally, if you wanted to talk to me directly, I’m more than happy to just take emails directly.

Roger Dooley: Great. Okay. We will have all those links on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Brian, thanks for being on the show.

Brian Sheehan: Great. Thanks, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at rogerdooley.com.