Do you spend hours a week in long and often unproductive meetings? Do you feel like the powers that be are unyielding and stuck in a never-ending cycle of refusing to listen to others who may have better ideas?

Do you spend hours a week in long and often unproductive meetings? Do you feel like the powers that be are unyielding and stuck in a never-ending cycle of refusing to listen to others who may have better ideas?

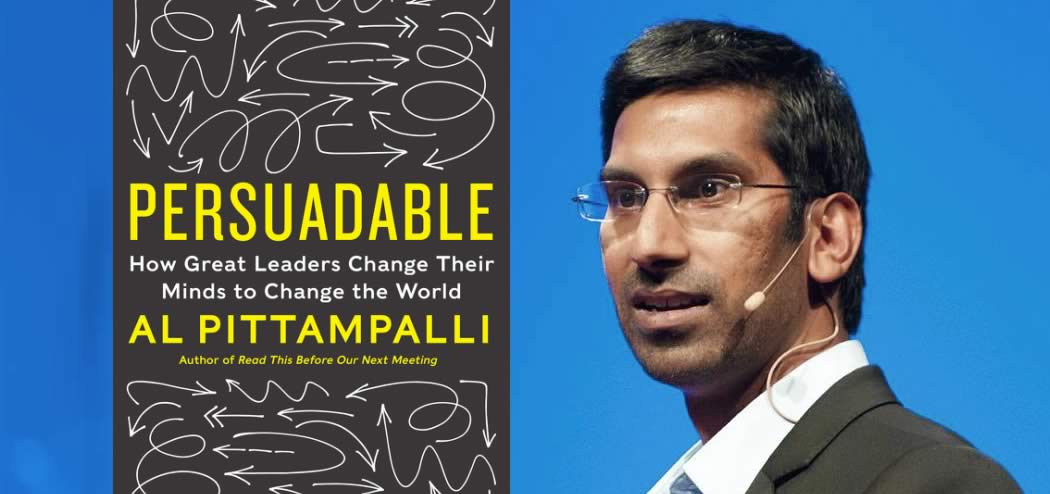

I am excited to introduce to you Al Pittampalli as this week’s guest on The Brainfluence Podcast. He is a best-selling author, subject matter expert, business consultant and writer for publications like Harvard Business Review, Fast Company, Entrepreneur and Psychology Today. He is an expert on persuasion and meetings, which I know are the bane of most people’s existence.

Al’s bestselling book, Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World, delves into how the willingness to change our minds is perceived as a weakness in our culture. In his book, however, Al uses decades of social science to reveal it as the ultimate leadership advantage.

While we have talked multiple times about persuasion, typically about how to persuade others or how to avoid being swindled by con artists, this interview with Al brings an entirely new theory to the table. Al and I talk about how being open to persuasion, at least some of the time, may make you a smarter leader and help your team, company, and life to be more successful.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why we still fall into the meeting trap.

- How to speed up and make your meetings more efficient.

- How to give yourself a competitive advantage over others.

- One of the traits that helps Warren Buffett and Ray Dalio to be successful.

- How to be right more often.

Key Resources:

- Amazon: Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World

by Al Pittampalli

- Kindle Version: Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World

by Al Pittampalli

- Amazon: Read This Before Our Next Meeting: How We Can Get More Done

by Al Pittampalli

- Kindle Version: Read This Before Our Next Meeting: How We Can Get More Done

by Al Pittampalli

- Connect with Al: Al Pittampali | Blog | Twitter | LinkedIn

- Brainfluence Ep #98: How to be a White-Hat Con Artist with Maria Konnikova

- Warren Buffett

- Bridgewater

- Jonathan Baron

- Kindle: Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare: Theory and Practice by Admiral William H. McRaven

- Kindle: The Power of Intuition: How to Use Your Gut Feelings to Make Better Decisions at Work by Gary Klein, PhD

- Steve Jobs

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. I’m excited to introduce this week’s guest for several reasons. First, he’s an expert in meetings, which in my rare corporate stints were the bane of my existence.

Second, he’s an expert in persuasion but not in the usual way we talk about here. Most often we’re talking about how to be more persuasive. When Maria Konnikova was on this show not too long ago, we talked about how to avoid being persuaded by unethical con artists. But this week’s guest explains why you should be persuaded, at least some times, and how to change your thinking so that you don’t resist being persuaded quite so much.

Our guest’s first book, Read This Before Our Next Meeting was a massive bestseller. His new book is Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World. Welcome to the show, Al Pittampali.

Al Pittampali: Great to be here, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Great, well hey, Al, before we get into Persuadable, let’s talk a little bit about meetings. Every productivity expert and leadership guru has a recipe for better meetings but it seems like many companies are still bogged down by meetings that are too numerous and they’re too long and really not very productive. Why is that?

Al Pittampali: Well I think that too many people have tried to kind of reform the meeting and make it better but I think that one of the most obvious conclusions I’ve come to is the fact that we just need to have less meetings to begin with. I mean the meeting itself is kind of broken the way we think about it. We just need to meet for really specific purposes and for other purposes, kind of the non-essential meetings I would call them, we just need to get rid of them.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think that sometimes people use meetings as sort of an excuse to avoid real productivity. I know in one of my corporate stints I had a person working for me and she was having difficulty making progress in new product creation and significant innovation, which was really her primary focus. When we looked at her schedule, she had more than 30 hours of meetings every week. In some weeks were there were some extra ones layered on top, it got closer to 40 hours.

I don’t pretend to psychoanalyze and it could just be that this was part of the corporate culture thing, but it seemed like the meetings were perhaps an escape from having to do sort of the hard creative work that maybe was a little bit more uncomfortable. As long you were in what seemed to be a mandatory meeting, you couldn’t really be criticized for not doing other stuff.

Al Pittampali: Yeah, I always say that the meeting is the best and most socially acceptable stalling tactic there is in corporate life, right? I mean it’s this amazing situation where you get to not have to make a decision and you look productive and you might even get promoted if you call enough meetings. So it’s kind of funny but it really is a serious problem. When you think about a meeting, just the term itself has lost kind of all meaning.

I speak at conferences all the time, these kinds of 1,000, 2,000 person events and they call those meetings. Then somebody asked me to get coffee with them the other day to pitch me an idea and we call that a meeting. The only thing these two meetings have in common is the fact that we call them both meetings, right? Meetings are kind of this catch-all term that we use to really avoid—a lot of times—avoid doing kind of the hard work of creation and connecting.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Is technology helping or hurting? I know that in the corporate environment that I was referring to they use—I think it’s Outlook or one of these sort of group scheduling things—where you can try and find those empty time slots and bring other people in your meetings. But it seems like you’re almost as an individual who’s trying to get stuff done setting yourself up to be interrupted by unwanted meetings because you’re putting your schedule out there and saying, “Hey, I’ve got these free hours here that are just waiting for you to schedule a meeting.”

Then there’s remote stuff too. It seems like these days you’ve got all these remote meetings where half the people aren’t in the room and they’re probably checking email or playing Candy Crush or something, but you don’t know.

Al Pittampali: Yeah, the problem with meetings is not that they’re not efficient enough. They’re actually too efficient in the sense that just with a click of a button we can schedule a meeting and interrupt like seven or eight people’s day in one moment. You know? Think about that. I mean, think about any other kind of expense in corporate culture where you could just so easily and so efficiently basically just do that with reckless abandon. I think that one of the challenges with technology is it’s getting easier and easier to do that kind of thing and more socially acceptable.

I always kind of had this thought experiment in terms of like what if there was some kind of friction to meetings? What if you had to pay a tax every time you called a meeting? Or you had to run around the building every time you wanted to call a meeting? I guarantee you there’d be way way less meetings and there would be more purposeful meetings because you’d have to actually think very hard about whether this meeting was actually worth it.

So I think that’s one of the things. Technology is not going to get us there. Technology is not going to get us out of this problem. It’s this kind of self-reflection and this understanding of prioritization to make sure that we’re only meeting for the important things because I’m not anti-meeting. I think meetings are extremely important. I just think that we should be meeting for the 20 percent of stuff that matters and then not meeting, making a decision and moving on, for the 80 percent that doesn’t.

Roger Dooley: You think things are getting any better? Or, not that you’ve noticed?

Al Pittampali: Not that I’ve noticed actually. I spend a lot of time going to organizations and talking to them about this subject and try to move the needle. And we do. We do get great results usually in small groups.

I mean, trying to tackle an entire corporate culture is a very very difficult thing to do. But, yeah, I think when it comes to smaller teams and smaller groups and kind of these little sectors within companies, when you have strong leadership and you have people that are really fed up with the status quo, you can actually get some change.

Roger Dooley: What about stand-up meetings? Does that help at all? Any of your people you work with try that as a means at least of shortening meetings for one and be probably—people might avoid those meetings more if they knew they were just going to be standing up in kind of an uncomfortable situation. Not being able to check their computer or whatever.

Al Pittampali: Yeah, there’s some good research on this actually. They have tested these kind of stand-up meetings and they turn out that that they are more productive. They are shorter. They are more purposeful because again it adds more friction to the process, right? When people aren’t comfortable, they’re actually uncomfortable, you have to think really hard about what you want to talk about and what the goals are because most people want to get out of there as quickly as possible.

The problem is, again, it’s a cultural problem, right? Because if you’re the only person in a culture doing these stand-up meetings, it feels weird, it feels awkward. Most people aren’t willing to go out on a limb. I applaud everyone that does because I think that’s what’s important. But I think that one of the keys is making sure that the top leadership are practicing what they preach.

So if anybody out there today who’s a leader of an organization or a department, if you hold stand-up meetings, then more likely the people around you will. You’re going to set the tone. So the way you operate and hold meetings is the way your people will.

Roger Dooley: Interesting. I’ve also heard about walking meetings but that’s really good for only maybe two or three people or something otherwise I’m sure it gets unwieldy, somebody having to walk like a campus tour guide or something backwards so they can address the group.

Al Pittampali: Yeah, I’ve never thought about that.

Roger Dooley: I’ve heard that’s actually a good way of getting people outside their usual thought process too, where you can get them into a different environment and perhaps open up their thinking.

So let’s move on to your new book Persuadable which is really a fun read, Al. It turned out to my surprise to be more of a psychology book than sort of a traditional leadership book because our brains are really set up surprisingly to not be persuaded very easily. I think most of our listeners are in the persuasion business of some kind. They’re in advertising or marketing or sales or they’re entrepreneurs trying to introduce new products.

I think they’d probably agree that it is difficult to change people’s minds. Some of the things you talk about of course are the same techniques that a persuader would use, they’re trying to sort of approach that non-rational side, the nonconscious side of the individual perhaps by using an emotional appeal or by appealing to some kind of cognitive bias that might exist. But we all carry a lot of cognitive biases that prevent us from being persuaded, right?

Al Pittampali: That’s exactly right. That’s really kind of one of the main goals of the book is to really explore that. Really to understand we all know that we have problems changing our minds, probably all of us are a little bit more stubborn, not as open-minded as we want to be. And the question is why, right?

Because intellectually if we talk about it, if somebody presents you with information that has a better idea than the one that’s currently in your brain, just logically speaking, you should want that idea, right? You should want to get smarter. You should want to operate more effectively in the world. Yet so often we reject it even when we know it’s probably a better idea. I wanted to understand why that is so we could really try to change it.

Because I think that persuasiveness is important, don’t get me wrong. Leaders being persuasive of course is a critical leadership skill. My argument though is that although we’ve taken great strides to become better at being persuasive, and you know, your audience has probably read tons of books on the topic, listens to podcasts like yours, Roger, attended seminars on that topic, we haven’t really paid much attention to the other side of the coin which is being persuadable, having the genuine willingness to change your mind in the face of evidence.

I argue that in a world that is changing faster than ever, that is turbulent, that is uncertain, it’s actually being persuadable that is at least as great of a competitive advantage than being persuasive.

Roger Dooley: I guess you could argue that an investor like Warren Buffet is an example of that because he seems to be able to take information and put aside preconceived biases and analyze the numbers, analyze the facts, and come to usually a pretty darn good investment conclusion. Where so many other folks have a particular axe to grind. They’re technology experts or they have some specific goal in mind as opposed to simply analyzing the facts and then taking action based on those facts.

Al Pittampali: That’s exactly right. I mean, if you look at the world’s top investors, at least some of them, what you’ll find is that they are obsessively paranoid about being overconfident.

So the person that comes to mind is Ray Dalio who I profile in the book. He’s the founder of Bridgewater, the largest hedge fund in the world. When we think about leadership, we think about confidence. In fact, confidence is kind of this word in our society when it comes to leaders that everybody wants to be more confident and everybody wants to be more certain in the face of criticism and uncertainty.

Yet, Dalio is the opposite almost. He has this great quote when people ask him about kind of how he’s become successful. He says it’s partly because due to the fact that he’s always fearing being wrong. He spends so much time in the day really second-guessing his beliefs. In fact, he’s surrounded himself with a team of researchers, scientists, mathematicians, people from diverse fields, for the primary purpose of second-guessing his thinking.

Why would anyone do that? The answer is because he knows that his brain is subject to all these cognitive biases and by putting smart people around him and being persuadable, being willing to listen to them, being willing to be challenged and to be scrutinized, the beliefs that come out of that process are going to be improved and they’re going to be the most accurate possible. It’s that kind of thinking, that persuadability as I call it, that has allowed him over time to become arguably the most successful investor in the world.

Roger Dooley: That’s not a dissimilar approach to Abraham Lincoln, right? You mention him in your book where he would have his team of rivals that would basically argue things out and he could then try and assess the facts and determine the direction.

Al Pittampali: That’s exactly right. One common trait of both of these leaders, Abraham Lincoln and Ray Dalio, is there not just open-minded, they’re actively open-minded. Now this is a crucial distinction here.

So when we think about leadership and we think about getting other opinions, we are, it’s almost cliché, right? Like we know that leaders are supposed to listen to other people and get divergent points of view and yadda yadda yadda, have debates and that kind of thing. But at best, they’re open-minded. But open-mindedness is a passive activity. It’s kind of like, “All right, I kind of believe this thing. I want to believe this thing. But I’m open to your opinions. Prove me wrong” kind of thing.

Active open-mindedness which is what Jonathan Baron, professor of psychology at University of Pennsylvania calls it, is a much more active process. It’s where you go out of your way to prove yourself wrong. It’s about saying, “Okay, I have these beliefs that I kind of like too much and I know I’m fond of this decision that I just made or this opinion, but I’m actually going to go out of my way to try to scrutinize it.”

As uncomfortable as that is, I’m going to find people that disagree with me. I’m going to put them in a room with me and I’m going to say, “You know what? You’re obligated to show me why I’m wrong.” That kind of thinking really accelerates the feedback loop and allows these leaders to grow at a far faster rate and get smarter and right more often than their peers and their competitors.

Roger Dooley: Well at the moment we’re in the middle of a US presidential primary and it seems like the politicians who might choose a more thoughtful approach, like perhaps Abraham Lincoln, are getting punished for that and it seems that voters are rewarding those politicians who have extremely strong, rigid beliefs, are not open to compromise.

They’re not open to changing their mind. They criticize their opponents if they ever change their mind. Why is that? I mean, it seems like it is obvious that you would want a leader to be thoughtful and not go down a blind alley that’s clearly wrong. But the voters seem to be actively looking for those kinds of candidates.

Al Pittampali: Right. One of the reasons for that is actually evolutionary in origin. We are hardwired to distrust inconsistency. I mean, ever since the beginning of time, we’ve needed to figure out whether the person in our tribe was our friend or our foe and if they acted inconsistent, right? If they broke a commitment or if they did one thing one day and then another thing the next day, we learned to distrust them because that was a sign that they may bash our head in the next day and steal our food. At least that’s the evolutionary logic.

So fast forward to today, when we see inconsistency, when we see what they call in politics a flip-flop, we instantly distrust that person. We instantly see it as bad. That’s what Daniel Kahneman calls our System 1 processing, our intuition. That’s our kind of automatic, kneejerk reaction. What we need to do though as consumers, as citizens, as voters, is to step back and ask yourself, “Okay, I know that’s what I feel. I know I feel like this was the wrong thing but let me actually ask the question why.”

Why did they change their mind? Because when—a lot of the politicians obviously which will not be news to anyone lie, right? They change their mind for purely political reasons, for selfish reasons, but other times when circumstances change, when facts change, it’s the intelligent thing to do to change your mind.

So we have to try to kind of distinguish between when an inconsistency or when a flip-flop is actually a thoughtful thing to do and when it’s a dishonest thing to do. That’s a hard thing. I think the media, you know, needs to responsible here and to provide context but I think that we as citizens can’t just sit back. We have to be engaged and we have to try to figure out who’s really the ones that we can trust and not rely too much just on our intuitive gut reactions.

Roger Dooley: You think there’s an element of dominance there too? That a leader who is uncompromising and unwavering comes across as a more dominant leader than somebody who is asking opinions and listening and perhaps behaving in a normal, positive way but is not embodying what people expect for a leader?

Al Pittampali: Absolutely. I think that in our culture in general there’s that kind of leadership archetype. I call it the traditional leadership archetype which is this confident, convicted, and consistent leader. We see that as strength. We see that as kind of somebody who is going to lead us during times of uncertainty and stuff but you know this is changing. I mean maybe not completely culture-wide but it’s changing.

Like for example, in the book I document Admiral William McRaven. Admiral William McRaven is the commander of Joint Special Operations Command, at least he used to be, he’s the guy who oversaw the raid to get Osama bin Laden. One of the amazing thing about that story when you read some of the books on the topic is you’re expecting the guy to have led the raid to get Osama bin Laden to be this traditional leader, right?

This confident, convicted, consistent guy but the administration was shocked to find that this guy when they brought him in for the first time was none of those things. In fact, they found that dissimilar to military brass—usual military brass—he was humble. He was open to suggestion and he was willing to change his mind.

From the outside, you could look at that and you could say, “Wow, this guy isn’t strong. In fact, that’s weak.” But the people who knew Admiral William McRaven because of his track record were smart enough to realize and know when the world is certain and when the world is simple, you want the guy who seems like he has all the answers, because he might.

But when the world is complex, and by the way Special Operations is extremely complex and uncertain, you don’t want the guy who has all the answers. You want the guy who is smart enough to admit that it’s not possible to have all the answers. You want the guy who’s willing to be humble, to be open to suggestion, and change his mind.

Roger Dooley: Makes a lot of sense. If more people would only get onboard with that I think. Moving over to the business world again, you have sort of the same thing happening where people idolize Steve Jobs and he was—although you do point out that occasionally he was slightly open to suggestions and changed his mind, like moving the iPhone ahead of the iPad in the product roadmap once he saw the technology that was developing.

Nevertheless, he is pretty much your top down leader who did not really consider other people’s opinions as being very important. When is that the right approach? Is he just like a one in a million person? Because he was right most of the time. Is that just an exception that should be ignored or are there some leadership situations where that’s the way to go?

Al Pittampali: Well, it’s hard to know with Steve Jobs. I mean, he could be a one-in-a-million example or he could be the one that we should all be emulating. It’s hard to know but I’ll give you this kind of rubric which is that we shouldn’t always be persuadable. Persuadability takes time and intention and cognitive energy and we just can’t be persuadable all the time. If you’re persuadable all the time, then you turn into this kind of perfectionist / somebody who’s paralyzed by decision-making and that kind of thing.

It’s funny, my first book and my second book kind of dovetail together because my first book which was all about meetings, the thesis was that we need to be, in the context of meetings, we need to be more decisive. Leaders need to be decisive because we are just meeting too often and often over very trivial things.

When it comes to these trivial things, we need to just stop meeting. We need to just trust somebody to stand up, make a decision, and move on. If we could just do that and leaders could be more decisive in that domain, then we would just get so much more done as an organization.

That being said, there’s often obviously times when we need to do the opposite, right? When the decisions are higher stakes, when it comes to important matters, a good enough decision isn’t good enough. We need a great decision. We need to avoid catastrophe when it comes to high-stakes decisions. In those situations, we need to be persuadable. We need to consider other people’s opinions. We need to second-guess our own thinking.

So leaders should constantly be moving back and forth between being decisive and being persuadable. But the core argument with this book is that we already know that we need to be decisive. In fact, most leaders at least pretend to be decisive or they assume they need to be decisive so they kind of live there. And occasionally when nobody’s looking, they’ll be persuadable. Then they’ll move back because they don’t want to look like a weak leader.

What I’m saying is instead we need to live in persuadability. We need to be persuadable leaders and every now and then we need to be decisive. But of course we need to be both. It’s just persuadability when it comes to the most important issues of the day, which is the one that we care about in an organization, that is really the critical leadership skill.

Roger Dooley: Al, you mention our brains conserving energy, that’s something that comes up a lot in my talks. It’s a key fact for marketers because if they want to appeal to that energy-efficient System 1 thinking that you mentioned, they can use emotional appeals. They can use other things that sort of fly under the radar like social proof or any number of somewhat nonconscious type cues.

But you point out that that tendency works against us as being open to persuasion too. That because it is energy efficient to not change our mind to reject new information that doesn’t agree with what we have, you have to overcome that. Just the fact that we all start with confirmation bias, I think. We tend to look askance at facts that don’t agree with ours unless we’re one of these well-trained deciders that you mentioned. But it’s really hardwired into our brain, isn’t it?

Al Pittampali: It’s absolutely hardwired into our brain and we need to fight against it every single day. Just think about the last time you were in an argument. You were in an argument and somebody raises a point that immediately triggers your kind of defense system. You get angry about it because to you it’s like rubbish, right?

It’s like, “What are you talking about? That’s ridiculous.” And yet there’s this very subtle sense of confusion because you’re like, “I don’t quite know why that’s wrong but I know it’s wrong.” It’s what Dr. Robert Burton, the neuro-philosopher, calls the feeling of knowing. You just have this feeling that that’s wrong.

The problem with that feeling is that it is often unreliable. It’s a kind of function of this cognitive miser part of our brain that wants us to maintain the beliefs that we have and to conserve energy. What we need to do is we need to actually learn to distrust our gut. We need to really learn that you know what? We need to sometimes—you know our intuition is really valuable and it provides us information but we have to treat it as just information. As Gary Klein says, “We should never trust our gut, our intuition, we should consult it.”

What we do need to do is engage in more effortful thinking and asking ourselves, let’s consider the opposite. So that thing that that guy said that I think is so wrong right now, ask yourself, well what if it were right? Under what conditions would I believe that maybe that this could be true what he’s saying? That kind of thinking is something that when leaders engage in it more and more, they end up being right more often.

They end up making better decisions because so often the obvious answer is not the right one. The one that jibes with our existing beliefs is not the true one. If you want to be right more often, if you want to be more accurate, if you want to be able to predict the future with more clarity and more precision, then you have to be constantly fighting against this feeling of knowing and this confirmation bias.

Roger Dooley: Do you have any tips for somebody who is working with a leader that either hasn’t read your book or didn’t really take it to heart and is suffering from all these various types of things that they are in System 1 thinking mode? They’re rejecting logical arguments. They’re not really seriously considering alternatives to their current thought process. Do you have any suggestions for how to break them out of that and perhaps sort of kick them into a more rational analysis?

Al Pittampali: So I have two answers for that. The first answer is I don’t want to let people off the hook because the immediate thing when people read my book is, “Oh my god, I love this book. I can’t wait to give it to my boss.” Or “I can’t wait to give it to somebody else because they really need it.”

The whole thesis of this book is to look inward and say, “You know what? Is it possible I’m the one that needs to be persuadable? I’m the one that needs to be convinced? I’m the one that needs to be more open-minded?” Because I think there’s great power in it. For a long time, I think people assume that if you do do that it’s because you’re this altruist, that you’re just being selfless, and you’re just being a nice person. But I’m trying to make the argument that there’s actually an advantage to doing that. I kind of lay that out in the book.

So, please, before you even think of about applying this to other people, apply it to yourself. That being said, of course you’re going to want to spread the gospel once you’ve really embraced this concept of persuadability and it’s not easy, right? I mean it’s very difficult to try to convince somebody who’s unpersuadable that they need to be more persuadable.

But if I were to give you one tip it’s this: do not try to convince somebody to be persuadable when you’re currently in some type of conflict with them. Because they’re going to assume you have an agenda and that probably has the benefit of being true that criticism because you probably do have an agenda.

What you have to do is you have to say, like in this book what I say to people is, “I’m not trying to push.” You know, I talk about politics, I talk about very particular moral beliefs, and I say, “I’m not trying to push any particular agenda. I’m not taking sides in the debate. I’m just trying to set the rules for the debate.”

That’s your goal with your boss. You’re not trying to push any agenda. You’re not trying to convince them of anything in that moment. You’re just trying to say, “Listen, boss, I just want to set the rules of the debate. I just want to make sure that we’re always arguing in a way to let the best ideas in, in a way that the best idea wins. Where we let the best idea prevail.”

Again, that’s no easy task but if you do it that way, if you approach things without content, just the structure, just trying to set up the rules, you’ll have a better chance of winning.

Roger Dooley: Right. I guess you could also say that you might have to employ some persuasion tactics of your own in that case to try and at least open up the discussion whether it’s say using a story that sort of flies under the cognitive radar or including a lot of graphs that illustrate your points that give you more credibility.

There’s a million of these things and perhaps choosing a few of those might at least get the discussion rolling because I think once that more powerful individual is in that rational analysis mode, then you can have a good discussion. But it’s up to that point that’s perhaps the hard part.

Al Pittampali: Yes. It is hard but it’s possible and people need to continue to try because it’s worth it.

Roger Dooley: One last thing I’ll ask you about, you talk about taking on your own tribe as a key element in being persuadable yourself. That sounds difficult to me, particularly since humans are still kind of tribal in our own ways. We prefer and we trust people that are most like ourselves. What do you mean by taking on your own tribe?

Al Pittampali: Well this book is not just about changing yourself. It’s really about changing the world because persuadability just isn’t an advantage for the individual, it’s an advantage for society. Can you imagine if we lived in a world where we all agreed to let the best idea prevail, right? Not just our own idea or our tribe’s ides. I know it sounds pretty kind of pie in the sky but I think that it’s possible to at least move the needle in that direction.

We have to recognize that we do operate within these tribes, right? There’s the Democrat tribe, the Republican tribe, there’s the Toastmasters tribe. There’s the Detroit Pistons tribe. We all are a part of these groups that govern what we think, what we believe. You know, when is the last time one tribe has ever stood up and convinced another tribe that they’re wrong?

It happens but it’s extremely difficult, right? Like when is the last time a Republican has stood up at the Democratic National Convention and given a speech that actually persuaded them that they’re wrong on something? It doesn’t happen.

So what we need is a few brave individuals who are willing to use the social currency they have with their own tribe to actually say—instead of somebody else saying you’re wrong, for them to stand up and say, “You know what? I think maybe we’re wrong.” I agree that’s incredibly difficult because that might get you criticized, that might get you kind of ostracized from the tribe.

But it’s so valuable because when we look throughout history, when we look at every successful social movement, every successful change, we always focus on the persuaders. We always focus on the Martin Luther King Jrs and the Mahatma Gandhi and the Susan B. Anthony. For good reason, right? I mean these were incredible people that changed hearts and minds.

But when we look at the product adoption curve and we look at how change happens, we also have to realize that in order for them to sell change, there had to have been people to buy. What we find is that people within tribes that were at odds with these people, prominent people actually changed their mind and took on their own tribe. That had so much influence that allowed the really social change to happen.

So it’s really my plea that—I tuck it in the final chapter because I think it’s the biggest ask I make, but that’s my plea to people. Is to find a way to take on your own tribe.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Al Pittampali, author of Read This Before Our Next Meeting and his newest book, Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World. Al, how can our listeners connect with you and your content online?

Al Pittampali: You can find me at AlPitt.com, that’s A-L-P-I-T-T dot com. And you can actually download the first chapter of Persuadable for free. Do that, read it. If you like it, buy the book. If you don’t, don’t waste your money.

Roger Dooley: Okay, great. We’ll have links to that site and any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/Podcast. We’ll also have a text version of our conversation there. Al, thanks so much for being on the show and giving us a view of persuasion from the other side.

Al Pittampali: Thank you for having me, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.