Many of us leap to conclusions when trying to solve our problems, whether they are personal, financial, or otherwise. But is there a better, more thought-out way to find solutions?

Many of us leap to conclusions when trying to solve our problems, whether they are personal, financial, or otherwise. But is there a better, more thought-out way to find solutions?

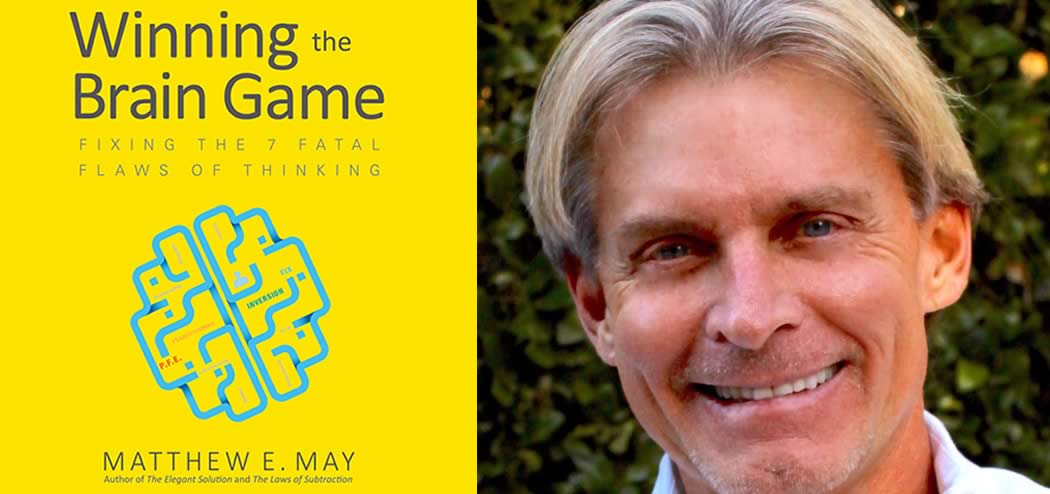

Matthew E. May is a specialist in critical thinking, as well as a prolific author of books about ideas and how to improve them. His new book, titled Winning The Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking, aims to point out seven common, yet destructive, flaws in our thinking patterns. Matthew’s book (and interview!) will help you understand these flaws, how you can change the way you think, and why it’s crucial to do so.

Matthew E. May is an innovation strategist and the author of five books, the latest being Winning the Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, AMEX Open Forum, Strategy+Business, The Rotman Magazine, Fast Company, and Harvard Business Review. Although Matt holds an MBA from The Wharton School and a BA from Johns Hopkins University, he counts winning the New Yorker cartoon caption contest as one of his most creative achievements.

Plug into our discussion on how you can change your thinking in order to solve problems by shifting your perspective. You’re sure to come away with techniques you can apply right away to enhance your critical thinking skills.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Matt’s technique of “frame-storming” and how it can help you look at problems from a new perspective.

- Why it’s important to avoid “analysis paralysis” brought on by overthinking.

- Why you can “satisfice” while you’re testing a new idea – but why you shouldn’t down the line if you want to avoid mediocrity.

- Why we downgrade our goals out of fear of failure – and how you can avoid doing so.

Key Resources:

- Connect with Matthew: https://matthewemay.com| Matt’s Column at Inc. | LinkedIn | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: Winning The Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking

- Kindle Version: Winning The Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking by Matthew May

- Matt’s Other Books:

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week is going to teach you how to outthink your competition. He’s an innovation strategist and the author of five books. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, strategy+business, the Rotman Magazine, Fast Company, and Harvard Business Review.

What really sold me on him as a guest though was that he actually won The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest. His newest book is Winning the Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking. Welcome to the show, Matthew May.

Matthew May: Thank you, Roger. Good to be here.

Roger Dooley: Matt, I’m surprised you just didn’t retire from public life after winning The New Yorker Caption Contest. That’s got to be the pinnacle of creative achievement.

Matthew May: Yeah, it must have been a fluke because I’ve entered several times since and haven’t had much luck. I don’t even think I’ve made it to the finalists. The fun part though, just a quick anecdote is that they have now gone to crowdsourcing the first cut among previous winners.

So every Monday I get an email from Bob Mankoff, the cartoon editor at New Yorker magazine with a link. We go through, each of us, all of us go through rating upwards of 5,000 of these things. So you can choose to do it or not, but that’s my claim to fame.

Roger Dooley: Wow, that’s pretty cool and probably saves them a little bit of work too.

Matthew May: I think so.

Roger Dooley: They must get a ton of captions and they have to have some way of screening them. So, yeah, that makes a lot of sense. What was the cartoon? I tried to hunt around and find it. I found one with a couple in bed wearing hazmat suits, was that the one?

Matthew May: That’s the one. It was, yeah, a couple in bed, both wearing hazmat suits. One turning to the other and my winning caption was, “Next time can we get flu shots like everyone else?”

Roger Dooley: That’s great. Did you apply any structured thinking in coming up with that or did it just sort of pop into your head?

Matthew May: No, I actually did. I used a bit of what I call synthesis, which is, gosh, the cartoon caption contest, it can’t be obvious except in retrospect. The way that I got around some of the obvious things—you know, people being in bed, motels, sex, all that kind of stuff, was to use word tags. I basically used a little bit of observation, tagged all the things I saw in the single panel.

Then used those as sort of jumping off points to think of all the various and assorted things associated with each of those word tags. Then combined those in different ways until finally I had about a dozen things that I liked. I had to choose between those and I just got lucky.

Roger Dooley: Well that’s great. Coming up with humor has got to be difficult. I really admire folks who write for like these nightly talk shows and so on. Of course, one thing they do is they employ a bunch of writers because any one person trying to come up with a full monologue packed with jokes and commentary, that’d be very difficult. But if you throw enough people at it, maybe even do a little bit of our outsourcing too, it can happen.

Matthew May: Yeah, I spent some time with a neuroscientist at UCLA here. For some reason, we got on the topic of humor and certainly observational humor seems to be the funniest of the humors rather than the constructed jokes. He said, “What we’re really laughing at is not the talent of any one writer or a joke line. What we’re laughing at is the recognition that we see ourselves in whatever that comedian or whatever that line may be and we’re laughing at ourselves.”

Roger Dooley: Let’s talk about your new book. Matt, you make a point that when we need a creative solution for a problem we often fail, sometimes miserably. You start the book early on by describing a meeting with a group of bomb disposal experts.

Now these are action oriented people who really have to find creative solutions to problems. Not only do they have to find these solutions, but they have to do it under great pressure of all kinds: time pressure, pressure from the consequences of doing it wrong, and so on. You gave them a problem involving shampoo to solve. Why don’t you set the stage up a little bit for our listeners?

Matthew May: This is probably ten years ago. I did a lot of work with the Los Angeles Police Department. One of the funnest groups I ever got to work with was the bomb squad. Bomb techs are all trained in one location no matter what unit they work for, police, military, they’re all trained in one place. They all have a common background. They are very, very high paid. Very type A kind of folks, to be honest with you. They have a little bit of an ego.

Roger Dooley: I would hope so. I mean, I hope they’re type As, not mañana types.

Matthew May: Yeah, these are the ladies and gentlemen that have to cut the little red wire so to speak that we all see on TV. I got to work with them because they had come to Toyota, which is where I was an advisor at the time. They wanted a little bit of help on thinking differently about a response to bomb calls, to bomb threats.

We were probably four years past the 9/11 point. Things had changed dramatically. There were newer kinds of enemies, terrorists and others on the front line. Old ways of dealing with bomb calls given technology weren’t working. So I got to work with them over the course of a couple of days. To loosen them up, I gave them a little thought challenge. The thought challenge really I thought would be right up their alley because it dealt with the theft. It was based on a real world problem.

I live in Los Angeles and I had heard a story of a Los Angeles upscale luxury club, a workout facility, that was having a problem with folks stealing these large bottles of shampoo from their stalls. Which doesn’t seem to be a big problem but these are very large bottles of shampoo and they’re salon-level only. Which means you have to basically be a licensed cosmetologist to buy these bottles. They’re $50, $60 bottles of shampoo, believe it or not.

Roger Dooley: So even the upscale patrons would be tempted to snag one now and then.

Matthew May: Absolutely. It was a very nice facility. The problem was that about a third of their patrons, about 33 percent of their patrons made off with a bottle of shampoo because it was free standing, wasn’t locked down, and put it in their gym bag.

They had tried a number of potential solutions. They had tried penalizing people. They had tried checking them in and out. They sell the bottles at the front desk. Reminders on the bottles themselves, “Please don’t steal. Respect your fellow patrons.” All these various and assorted things never moved the needle on the 33 percent theft rate.

I knew what the employees actually did to eliminate the theft, at least temporarily. But I turned it over to the bomb techs to sort of loosen up their right brain, get them thinking differently. They did what every other group that I have seen attack this kind of problem, and other challenges like it, they did immediately what everyone else sort of does.

They actually exhibited all of these things that I’m calling fatal thinking flaws. By and large, we’re not able to solve the problem, at least in the way that the employees were able to solve it. They can up with a host of different ideas.

Roger Dooley: Now you gave them ten minutes I think, Matt, we aren’t going to pause this show for ten minutes, but if any of the listeners do want to pause the recording and think about it for a few minutes, they’re free to do so and then turn it back on. So anyway, continue.

Matthew May: Yeah, and I put them in a box. And I’ll put your listeners in a box, too. In other words, I’ll give you some constraints. These were the actual constraints that the manager of the health club gave his employees:

- Low or no cost solution. Talking pennies. They had spent money, it wasn’t working.

- They did not want to alter the offering in any way. They wanted that free standing bottle of salon level shampoo.

- Not a miniature bottle. Not anything less than that.

- Had to be freestanding.

- Couldn’t interrupt the normal operation of the health club in any way.

- At the same time, you couldn’t put any further burden on the patrons, because these were fairly wealthy people and they didn’t want to disturb them or burden them in any way.

Those were the constraints. And ten minutes, as you mentioned, was the final constraint. So that was the problem. Are you looking for me to give you a solution?

Roger Dooley: Yes, we can proceed. I think now is the time for a spoiler. Or perhaps you could throw out some of the incorrect obvious ones that people came up with.

Matthew May: Oh, yeah.

Roger Dooley: Like putting it in a dispenser, which doesn’t really satisfy the needs—although, actually, from what I’ve observed in both health clubs and even some upscale hotels and cruise ships, that’s actually the solution for people making off with even all the little bottles.

Matthew May: Yeah, you know, that’s the obvious solution. Interestingly, I had an interview with a gentlemen last week and he’s a member of one of these clubs. He said, “That didn’t solve the problem. It doesn’t solve the problem at our club because people bring in their own empty bottles and just fill it with the shampoo from the pump top dispensers that are locked to the wall.”

Roger Dooley: Oh, they’re motivated.

Matthew May: So didn’t solve the problem but that was the sort of the obvious one. There were things like RFID. There was monitors. There was, you name it, half-empty bottles of shampoo. Holes in the top.

But what the employees decided to do was to simply remove the tops of the shampoo bottles. Immediately theft was stopped. The root cause of that problem was just simple accessibility. It wasn’t that people were necessarily evil or dishonest or hardwired criminals in any way. It was just easy to do.

Once they made it not so easy to do, the thefts stopped. A lot of people will say, “Well that’s a terrible solution. Water gets in the bottle” and da da da da. There are a lot of “yeah, buts” to that particularly solution but by and large it met all of the constraints and solved the problem in the real world.

Then I was able to sort of debrief all of the things that the bomb tech teams had done in solving the problem. It loosened them up. It met the goal. It actually was the kind of thing that I spent the next ten years giving all sorts of groups and people at all kinds of levels and different functions and jobs all over the world and sort of tracked their behaviors in trying to solve the problem. That’s where sort of these thinking flaws come into play. It’s observations over the course of about a decade. At this point, over 100,000 people have tackled these kinds of challenges.

Roger Dooley: Right, so you identify seven flaws. The first one is leaping. Explain about that, Matt.

Matthew May: This is jumping to conclusions, leaping to solutions. Gosh, that’s what the bomb techs did. They right away went into good old brainstorming. It is the most prevalent thing that I see. Anytime you give a problem to someone, the first thing they want to do is toss out an idea or a solution. There’s good reasons for it.

At this point in our lives, we probably solve most of our problems with a quick workaround. We don’t need a complex solution. We don’t need to think deeply around why is there traffic on the freeway? How do I get to work? Am I going to have tall, grande, or venti today? They just are sort of workaround solutions to surface level or routine problems.

The difficulty is we do it so often that when we’re given a tougher challenger, we use that de facto methodology and we toss out all the workarounds and top of mind solutions. Lo and behold, what happens is we come up with unsatisfactory solutions. Solutions that potentially make things worse. The problem remains unsolved.

Roger Dooley: So a brainstorming approach is fine for straightforward problems but if the problem is more the kind that defies easy solution, then that tends to be the wrong approach because people get stuck in that sort of rut.

Matthew May: We’re so good at brainstorming, we’ve been taught for years. And we’ve also been taught by our teachers in school to get an answer within a certain period of time and that answer has to be the right answer. So we’ve become conditioned to not asking questions but tossing out solutions.

The interesting thing is that’s not how we came into the world. You think about little kids, all they do is ask questions, and a lot of them. Why? Why? Why? Why? All the time they’re asking questions. We forget that once we get into school and then when we get on the job and into our professions. Likewise, we forget to ask questions.

We’re in such a fast-paced business world that no one wants to do anything that feels like slowing down the process, slowing down business. God forbid someone sees me in my office just daydreaming, what looks like to be daydreaming, and not working, not doing.

I’ve learned that trying to ask people to slow down and think more deeply is counterproductive. No one wants to do it. It doesn’t work. They’d rather feel like they’re doing something and tossing out solutions. So I’ve come up with a technique that I’ve injected into the whole problem-solving process that seems to work very well. It’s called framestorming.

Roger Dooley: Explain that.

Matthew May: Framestorming is very much like brainstorming except with brainstorming you are tossing out ideas and solutions and answers. With framestorming, you’re tossing out questions. “Why this? Why that? What if? How might we?” You’re coming up with a host of different questions that basically enable you to look at the problem from different perspectives. That really is the source of creative solutions, innovative solutions, resourceful solutions. It’s simply looking at the same problem through a different lens.

So framestorming is reframing the problem that you’re given. For example, in the shampoo case, given all the constraints that I put people under, you could reframe the problem by saying, “How do we make it completely unattractive and inaccessible to put a bottle of shampoo in one’s bag?” Once you reframe your problem like that, then the brainstorming can happen and you’re far more likely to come up with an elegant solution to the problem.

Roger Dooley: So really it’s rather than brainstorming solutions to a well-defined problem, you are brainstorming ways to reformulate the problem?

Matthew May: Yeah. It feels like brainstorming, so people don’t have an allergic reaction to it. It feels like they are moving ahead and they are solutioning. Because we have sort of two parts of our brain. The one part that wants to think more deeply thinks slower and requires a lot more mental energy and we resist that. So this little trick, this sort of cognitive trick, gets around that.

Roger Dooley: So it’s kind of funny, in the book you describe a simulated fire exercise involving you reacting to situations that a policeman might have to react to and either firing or not firing.

I just last week, I spoke to another author, Amy Hermann, who trains law enforcement officers including folks like Hostage Rescue Team and SEALs and so on to observe using artwork, which is really a fascinating kind of thing. I’d encourage our listeners if they happened to miss that episode to check it out. But she did one of those too and pretty much took out all the good guys and failed to take down the bad ones at experiment.

Matthew May: Oh boy, they got their revenge on me. They actually took me out to the LA Police Academy and set me up with a firing simulation. It’s basically a gun. It’s wired to, at the time, it was like a video kind of game machine but it was real world people in situations. Yeah, the first time I got killed because I reacted too slowly. The second time, I killed an innocent person who was pulling out a wallet that I thought was a knife or a gun. They were rolling on the floor. They got their revenge.

Roger Dooley: Why is that exercise so hard for civilians do you think?

Matthew May: Well, we’re not trained. If you can think back to the very first time that you were a child or you have a child and you throw a ball to them. What do they do? It probably hits them right in the chest, right? They don’t have the heuristic in the pattern, that rule of thumb if you will, mental rule of thumb in their brain yet.

It would take you a few times before they were able to catch it. But once they catch it, they’ll probably never have to think about it again because it’s there. It’s sort of hardwired, locked in. That’s what these quick reaction, one-shot learning is all about.

So we don’t have the discipline. We just haven’t been taught to look at the right things. Look for the right visual cues and react to them in a way that experience has shown by others to be the most successful. I think civilians who are untrained are bad at but civilians who have gone through training get good at it, just the way children do when you learn to toss the ball to them.

Roger Dooley: One of the things that I like about your book, Matt, is that in each of the flaws you get into the neuroscience of that particular flaw and how to cure it. In the case of leaping, you talk about Kahneman’s division of thinking into System 1 and System 2. I often bring that up when I’m talking to groups.

Usually I’m suggesting that they do not want to—if they’re marketers, which is probably the most common kind of group that I talk to—is that they don’t want to push their customers into System 2 where they’re doing this sort of cognitive rational, logical analysis because often, at least from a marketing standpoint, the outcome of that is no decision at all. Suddenly the problem gets really complicated and they say, “I’ll have to think about this some more.”

But in your case, what you’re really saying is that you want to push yourself or others into System 2 when you’re trying to avoid the danger of leaping to one particular conclusion.

Matthew May: Absolutely, yes. You bring up a good point which is actually one of the other sort of fatal thinking flaws which is the notion of overthinking. If leaping is not thinking enough, then overthinking is on the other end of the spectrum too much. You’re right, it ends up being a case where you’re paralyzed by analysis. Analysis paralysis and all of that.

Actually, sometimes you end up not only not doing anything but making the problem potentially worse and creating problems that weren’t even there to begin with because you’ve overthought it.

Roger Dooley: Jumping ahead to one of your other flaws: satisficing. That term was coined by one of my idols, Herb Simon, at Carnegie Mellon and ultimately a winner of the Nobel Prize. In business, it means doing the job well enough, more or less, because for decades if not centuries economists and business experts thought that managers attempted to maximize profits. That was the economic golden rule.

But what Simon observed was that in many or most cases, managers just did well enough to satisfy their various constituencies and that maximization beyond that often didn’t take place. That’s not perhaps entirely bad all the time in business because it’s somewhat of an adaptive strategy too I think. But why is satisficing bad when it comes to creative problem solving? And define it in the context that you use it too.

Matthew May: I think you’re accurate in your definition there. Satisfice is not our word, it’s Herb Simon’s word. It’s satisfy plus suffice. I think that in business there is a time and a place for it. You could say, “Well, gosh, 80/20 rule. Give me the 80 percent solution and then just let me sell it.” There’s a time and a place for that.

But when you are trying to solve a difficult problem with an elegant solution, satisficing won’t get you there. It will just lead to mediocrity. Now, let me put this in the context of say someone coming up with a new product or a new service. There is definitely a time where you do not need a perfect solution. That’s when you’re beginning.

You want something that is a satisficial solution so that you can exact user behavior from it and see if your idea has prayer of a chance of working. You’re not necessarily trying to validate that it’s a great idea, but you just want to figure out if it’s—make sure that it’s not a bad idea.

For that, you don’t need anything that is on the other end of the spectrum of maximizing or a maximal solution. You need something that’s minimal. You need something that will just get you to the next point. But when you have a finished product, a finished service, if you put something out into the marketplace, a problem solution, a strategy, that is mediocre, that is satisficial, it’s a satisficing strategy, you put yourself at the mercy of a better solution, the winner in your category or your segment.

When there is a clear winner and that is not you, that winner can use the resources that accrue to a winner to beat you up all day long in business. That’s something to be very conscious of, very careful of. Me-too kinds of solutions work if you decide that you’re going to take sort of the lowest cost provider status and position it in the vertical or the market, the segment that you’re competing it. But that’s a very, very difficult strategy to sustain.

So, there’s a time and a place for satisficing but when you’re trying to come up with an elegant solution, a final solution, and build a business around it, that’s not the time to do it.

Roger Dooley: Probably safe to say that Steve Jobs didn’t really permit a lot of satisficing when folks were working for him proposed various designs and tried to perhaps push back against some of his seemingly impossible specifications.

Matthew May: You know, gosh, I’m sure your audience has read the biography or various biographies or seen movies about Steve Jobs. Yes, he did not allow, at least consciously, knowingly allow, a less than in his mind perfect solution to enter the market. Now, there is no really such thing as perfection so things do go wrong but I can’t remember, at least in my lifetime having an Apple solution that was an 80 percent, a me-too, a mediocre product under his watch.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think he set goals that actually were no doubt in many cases seemed to be impossible, or nearly so, and forced people into these creative solutions because they did not have the opportunity to say, “We can’t do two tenths of an inch thick but we can do three tenths of an inch.” That wouldn’t have worked. Then the thing that might be even worse than satisficing is downgrading. What’s that about?

Matthew May: It’s a very close cousin to satisficing but this is when you consciously voluntarily force a formal revision of a goal. So Steve Jobs has a goal of xyz and his team comes back to him and says, “We’re going to give you 90 percent of xyz.” You can imagine how that probably would go over. But that downgrading of a goal happens a lot because we don’t like to fail.

But downgrading is basically that formal backwards revision of a stated goal. Simply so that we can declare victory at some level, which is kind of, it’s almost perverse if you think about because it’s kind of like preemptive surrender, right? You’re surrendering the initial goal just so that you can declare victory. Surrender. Victory. At odds with each other.

Roger Dooley: Although it seems like there’d be some management situations where that does make sense, where a manager might set a goal that’s very aggressive and at some point if the team is 90 percent there, perhaps that’s good enough for the market. Perhaps that other 10 percent would cost twice as much in terms of time or money and maybe wouldn’t lead to sufficient additional sales or profits.

Matthew May: Then that’s fine because then that’s deeper thinking that you’re employing to revise that goal. But when it’s a willy-nilly, “Oh my gosh, I can’t see the solution right away so here’s my solution that’s the 90 percent solution.” So it is very close to satisficing but you formally declare that at the get-go we think the initial goal is impossible. We do think that xyz, which is less than the original goal, is possible.

So downgrading is what we do when we can’t find that elegant solution right away. We tend to lose steam. We get discouraged. We begin to contemplate failure and rather than casting about looking for ways to springboard our thinking in new directions, get a little bit off road, we give up. That’s what downgrading is really all about is giving up when you shouldn’t give up.

So it’s a different situation than the one you described but absolutely there are times when it makes sense to revise a goal when the learning that you’ve done in the marketplace suggests so.

Roger Dooley: Do you have a suggested way or approach, Matt, for our listeners to attempt to solve a problem if their business has some fairly challenging situation ahead, whether it’s product related, maybe it’s financial? Do you have a suggested framework that is simple to implement or use that would let them apply some of these techniques and most importantly avoid these seven mistakes?

Matthew May: You know, I have over time I have sort of shied away from a step-wise approach to things. My approach mostly is that of a situational or contextual problem solving. So whatever the problem might be, I use sort of a going in proposition that what appears to be your problem probably isn’t. Therefore, whatever solution you’re probably contemplating isn’t the right one. And what appears to be impossible to you probably truly isn’t if you look at things from a different perspective.

So I take the approach that I can’t approach every problem in the same way, neither can a business. You have to sort of do what any good scientist does and any good conscious problem solving does. I don’t think there’s anything new or radical about that approach.

You gather as many facts as you possibly can. You observe as best you can. Try and diminish your biases and your assumptions. Frame up the question properly as best you can. Then go about thinking about solutions to that provocative framework. Then testing them out in a scientific way, a minimal way, experimenting, getting learning, getting feedback and iterating from there.

So it’s not a new or unique framework, but there are things that get in the way of that particular framework and that’s what I’m really interested in. I’m not here to push any kind of method. It’s simply how do you remove the obstacles that might get in the way of your native creativity and your native innovative ability? Because we all come into the world that way. Watch children in the sandbox out on the playground. Gosh, they’re imaginative. Oftentimes, it’s just getting back to that.

Roger Dooley: That’s probably as good a place as any to wrap up. I’ll remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Matthew May, author of Winning the Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking. Matt, how can our listeners find you and your content online?

Matthew May: It’s very easy, matthewemay.com. There are two Ts in my name. Middle initial is E., Matthew E. May. Every handle in the social world that I have is Matthew E. May. So Twitter is @MatthewEMay, LinkedIn is Matthew E. May. Facebook is Matthew E. May. Little bit of symmetry there.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well we’ll link to those places along with Matt’s books and any other resources we talked about during the show on the show notes pages at roogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Matt, thanks for being on the show.

Matthew May: It was fun. Thank you, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.