More often than not, the eight-hour workday feels like a mildly productive slog. Some people work more quickly and efficiently  than others, yet everybody is held to the same clock-in, clock-out schedule. So how can working less actually boost productivity, creativity, and success across the board?

than others, yet everybody is held to the same clock-in, clock-out schedule. So how can working less actually boost productivity, creativity, and success across the board?

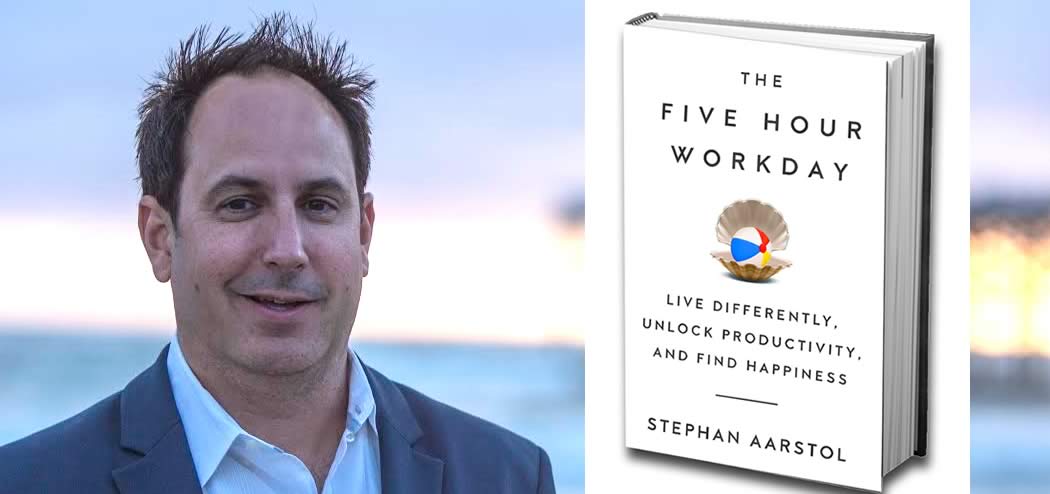

Stephan Aarstol of Tower Paddle Boards is also the author of The Five-Hour Workday: Live Differently, Unlock Productivity, and Find Happiness. After experimenting with shorter working hours last summer, Tower’s performance improved so much that the company’s five-hour day is now an integral part of its design.

Stephan and I cover a lot of ground in this interview: his appearance on Shark Tank, why the United States has some of the lowest happiness levels of industrialized countries, and how Tower has evolved into a beach-lifestyle brand are just a few of the highlights. The Five-Hour Workday challenges the stagnant workweek to catch up with the technological advances of the last few decades. Stephan has built Tower into a riotous success, all while leaving more time for happiness, hobbies, and fun in his life.

Stephan Aarstol is the CEO and founder of Tower Paddle Boards, an online stand up paddle boarding brand. You may remember Stephan from ABC’s Shark Tank, where he secured an investment from Mark Cuban. While Tower began as a disruptive, direct-to-consumer stand up paddle board company, it has evolved into a holistic beach-lifestyle company.

With a three-year growth rate of 1,853 percent, Tower was named the Fastest Growing Company in San Diego by the San Diego Business Journal, and was featured in the Inc.’s 2015 500 List of America’s Fastest Growing Companies. Tower’s success has yielded additional beach-lifestyle products, a travel and lifestyle magazine, and another episode of Shark Tank — this time about how Tower has become one of Mark Cuban’s best-performing investments from the show.

Stephan’s insights on entrepreneurship, online marketing, and productive business models have turned him into a highly sought-after thought leader in his industry. His work has been published in the Washington Post, Inc., Forbes, Entrepreneur, Fast Company, Mashable, and many other prominent business publications.

Stephan believes that many more of us can be free from the outdated eight-hour workday. Tune in to hear how, and pick up even more of his wisdom along the way!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How you can shape your business around a shorter workday and become even more successful.

- How the five-hour workday model can work for jobs outside the knowledge-industry, like customer service and manufacturing.

- Why time constraints are essential for productivity.

- How to make your business more efficient despite spending less time at the office.

- Where you can find Stephan’s free collection of productivity hacks, which have helped Tower grow exponentially.

Key Resources:

- Connect with Stephan: Tower Paddleboards | The Five Hour Workday | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: The Five-Hour Workday: Live Differently, Unlock Productivity, and Find Happiness by Stephan Aastol

- Kindle: The Five-Hour Workday: Live Differently, Unlock Productivity, and Find Happiness by Stephan Aastol

- Tower Lifestyle Magazine

- ABC’s Shark Tank

- Inc.’s 2015 List of the Fastest Growing Companies in America

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is another first. We’ve had the top selling business author ever, a Nobel Prize winner, but we’ve never had a Shark Tank contestant on the show, much less one that got a deal with Mark Cuban. Stephan Aarstol is the CEO and founder of Tower Paddle Boards, a company that registered a three-year 1,800 percent growth rate to earn a spot on the Inc. 500 list.

Tower is now morphing into a beach lifestyle company with brand extensions that include a magazine, sunglasses, and more to come. Stephan is also the author of a new book, The Five-Hour Workday: Live Differently, Unlock Productivity, and Find Happiness. Welcome to the show, Stephan.

Stephan Aarstol: Hey, Roger. Thanks for having me on, I appreciate it.

Roger Dooley: Great, I think that Shark Tank is syndicated globally, Stephan, but if any of our listeners have not seen the show, it brings entrepreneurs in front of a panel of five billionaire investors. The entrepreneurs pitch their concept, answer tough questions, and may or may not get a deal. Stephan, do you know what percent of the entrepreneurs that present on Shark Tank actually do get a deal?

Stephan Aarstol: It’s probably, I would say 25 to 50 percent, probably close the deal on the show. Maybe it’s closer to 50 percent.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it seems like it’s less than half. I know it varies on some shows. I think I’ve seen the occasional show where they went through the entire roster and maybe the last person got a deal but then others where multiple successful deals happen.

But you know I really like Shark Tank because it’s one of the few shows on TV that portrays business people and entrepreneurs in a positive way. Seems like most scripted dramas, particularly crime shows, don’t get beyond the greedy CEO—willing to murder anyone who’s inconvenient—stereotype.

The one thing I find a wee bit annoying about Shark Tank is the sort of oddly-scripted intros that the entrepreneurs use. I don’t know if it’s because these folks aren’t professional actors or announcers but the intro segments just seem a little bit, well, unreal to me.

Once the entrepreneurs start answering questions, then it strikes me as being a lot more real and from the heart but you pretty much sort of skipped the scripted info in your segment. In fact, you mention in your book that it’s known as perhaps the worst Shark Tank pitch ever. Explain what happened there.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, I mean I’m not an actor or really even a presenter. I’m a business guy, right? You’re going on TV and the show is most interested with this being entertaining. So they want you to have this sort of slick introduction that is exciting and dramatic. I tried to do that but they’re like, hey, you’ve got to pump up your energy. So they sort of coach me up on this and then I have a horrible memory.

So the idea of memorizing a two to three minute spiel is almost impossible to me. So I practiced that for days in the hotel. Then I went out there to do it and then my slideshow screwed up so I lost the train of my thought. I froze. I was literally silent for like minutes on end. The sharks were tearing into me. It was really this horrendous on-screen thing. Then of course I knew this was going to air to all these people, so I had to dig myself out and come back.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, that’s sort of the ultimate presenter’s nightmare for folks who speak or do presentations where you push wrong button and it wipes out your entire presentation. Then to compound it, forgetting what you’re going to say.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, but for TV it was actually good. They said I wouldn’t have even aired if they didn’t have this like dramatic start to it because it was kind of a dry presentation. But that made it like this Rocky-like comeback where the guy got beat up and then he fought back.

I ended up getting a deal from Mark Cuban for $150,000 for 30 percent of the company. Then he also negotiated for first right of refusal to invest in any business I do in the future, which was a first in the history of Shark Tank. It wasn’t like an investment just in this business because nobody even really liked the paddle board business. But they’re like, hey, this guy is an internet marketer, I could use him for other stuff. So it was kind of an investment in me.

Roger Dooley: That’s great. Do you think that maybe the rough start actually helped? That you seemed sort of vulnerable and you didn’t come off as one of these slick salespeople?

Stephan Aarstol: Well it helped me air was the big thing. Like when you were talking about how many deals close, like you’re right, it’s under 50 percent. I was guessing maybe 25 to 50 percent. But then another half of those, like after the fact when the due diligence is done, then those don’t close. So it’s really a small percentage where the money actually gets placed with the company.

Then you want to air, too. You can do the deal and not even air and then you’ve given away a chunk of your company and you don’t even get the benefit of the exposure.

Roger Dooley: Right, wow. I didn’t realize that was even a possibility. I guess you still have the deal and hopefully the assistance of the shark or sharks but you really miss that national exposure.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, I mean I kind of looked at Shark Tank, I mean I wasn’t really super needing to raise money. It was nice, but I was looking at it like a celebrity endorsement. Like I wouldn’t have given anybody else that deal except Mark Cuban. But I looked at him, he’s going to give me a celebrity endorsement and he’s going to give me $150,000 and I have to give him 30 percent of my company for nothing was kind of how I was looking at it.

Roger Dooley: Right, well you must have really been convincing because I’ve seen Mark eviscerate some other folks who were in the digital marketing space. There was an SEO guy a while back who went on and Mark really just killed him. So that speaks really well.

Stephan, one thing that you did was have an attractive assistant, an attractive female assistant I should say, in a small bikini demonstrate your paddle board product. Did you get any pushback on that? I think there’s some good psychology there that I’ll get into in a second but did anybody find that problematic?

Stephan Aarstol: When I pitched the initial show, my initial tape to Shark Tank, that was my roommate. So I just had her in the video. Then when I pitched it to Shark Tank, I had no intention of bringing her, but they’re like, “Hey, that blonde in your video. You should bring her on the show.” This is what the producers told me. So I brought her on the show and then we went up there.

Then we were doing our dress rehearsal to the producers the day before and you can get cut at that stage if you’re not good. The only thing they said was she’s too hot for TV. So I had to get a bigger bikini.

Roger Dooley: Oh, that was the big one.

Stephan Aarstol: We had all the ABC’s standards people, like you know, going through this whole thing. We got delayed the next day because of this. But you know, obviously that helps on TV. It has nothing to do with the pitch. We did get a little kickback from like the paddle board community and some people, but I mean, that’s how they sell everything to be perfectly honest.

Roger Dooley: Right. I watched your segment on YouTube, or a portion of it anyway. If that was the bigger bikini, the original one must have really been interesting. But you know, there’s some good psychology there because research shows that when males view a photo of an attractive woman, they become more impulsive and more short-term oriented. I don’t think anybody has studied the effects of a live model ten feet away but I have to believe they’re even more powerful than just viewing a two-dimensional image. So at least for the male sharks, and of course it’s always predominately a male group, that was probably a good thing.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, and Barbara really didn’t like me and I think it was because of the bikini. Barbara called me a nerd, she called me a leprechaun. She just tore into me and I think it was because the guys sort of liked it. I don’t think she really liked it.

Roger Dooley: One lesson, and you partly alluded to that already—I’ve done a variety of investment deals and, boy, price and ownership percent are really a pretty small part of the entire deal structure. You’ve got to deal with stuff like compensation and what happens if the business goes south and all these other really important issues. All we see on TV is, yes, here’s the dollar amount and here’s the percent. How does all that other stuff get done?

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, to do a deal like that where you’re going to give somebody, especially a billionaire, an equity stake in your company, you’ve kind of got to protect yourself. So when I first started shopping around to get lawyers, they were talking about $20,000 to do that deal. Just the legal fees from it. So imagine the person who goes on Shark Tank and gets $50,000 and they go to spend $20,000 to land that deal.

Even for a $150,000 investment I just thought that was insane. I ended up negotiating down to about $6,000 but I wanted to protect myself so I didn’t get into a situation where I could basically get “Facebooked” out of my company. If you’ve ever seen the Facebook movie, how the partner just sort of gets marginalized out of the company by some financial wizardry or whatever they’re doing. So you have to protect yourself there.

Roger Dooley: Right, that makes sense. Do deals fail in that phase even though they were concluded on TV, then they just don’t quite make it later on?

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, I think a lot of people exaggerate on TV because there’s nobody—it’s all live. You say whatever the heck you want. You can make up numbers. Nobody knows, right? So then after the fact, the shark’s team or the shark themselves does due diligence on your company.

If you were exaggerating your numbers or certain information didn’t come out, they’ll reject the deal. Some of the sharks are better than others at actually following through on their close. I think some of them, they close a very little percentage of their deals. They just want to make it for good TV, like they’re doing the deal. Then they don’t really follow through. But Cuban in that regard, he closes on most of his deals.

Roger Dooley: Interesting. So let’s talk about your new book, The Five-Hour Workday, and you practice that in your company. It seems completely counterintuitive, particularly to Americans who in general regard a long workweek, many hours and so on, as the path to success and even pride themselves on working more than other cultures.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, we’ve really sort of grown into that. It’s sort of capitalism gone awry, where we’ve become a very one-dimensional nation that we are defined by what we do for a living. That’s usually the first question you get from somebody. But the reality is, in the modern world, in this sort of information age, we’ve gone through this transition over the past 20 years where what used to take us eight to ten hours to do we can now do in two to three hours because there’s all of these productivity tools. Just a smartphone, a cell phone, all of the software that we’re using.

It’s just amazingly efficient to do stuff today, like we’re doing this interview over Skype instead of flying out there. There’s just all of these advantages. People sort of haven’t realized that and they’re not using these tools because they haven’t had to. Productivity in the country, even without using a lot of these tools, has gone way up. But, we’re still spending eight to ten hours a day in the office doing basically two to three hours of work.

So what I’ve done as an entrepreneur, because I was an independent entrepreneur for about the last twelve years, and a good portion of this was just working on my own. I went from this rigid 9 to 5 schedule to just going in, getting my work done, and getting out of there. This is what all of my entrepreneurial friends are doing and they’re thriving doing this.

It’s a big contrast from the corporate world where you’re going in there, you’re kind of watching the clock, you’re trying to impress people by getting in early and staying late. It’s not really focused on productivity, at least not for a lot of workers. What you have is you have some workers that just do two to three times the work of everybody else and then there’s some people who really are doing nothing and it’s all been judged by time.

So the world has changed and our workday is basically the same as what was invented for factory workers 100 years ago by Henry Ford. The eight-hour workday was just a fabrication, an invention, by a man in the U.S. It’s much different in other countries. In India, they work six ten-hour days. In Mexico, they work six eight-hour days. France has a 35-hour workweek.

There’s all these different workweeks all over the world, but in America, if—and I’ve got a lot of pushback from this—as soon as you start to challenge the idea of an eight-hour day, people think, “That’s stupid, that’s crazy. That’s impossible. That’s the way it is.” But if you look back 100 years ago in America, people used to work 10 to 16 hours a day, six days a week.

The Industrial Revolution came along, the assembly line came along, and all of a sudden, these people were not leaning on brooms anymore in the factories around the world and America. They had to keep up with the assembly line. So productivity had this overnight shift of basically a 10X shift and Henry Ford saw that. And workers were dying on factory floors and being injured. I mean, it became a really hazardous environment to health to sustain these long hours. All of a sudden, people were ten times more productive.

Roger Dooley: In his case, he saw that he could afford to cut back.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, because he had these huge productivity gains. So how do you react to that? You work these people to death and take all the money at the top? That’s what was happening during that day. That’s where the robber baron class came from.

You fast forward 100 years, we’ve gone through the exact thing transition. Except this time, it’s the information age and these productivity tools for the mind, where it was productivity tools for the body before. Now, we have similar unhealthy things happening in society. We’ve got stress-related diseases are through the roof. We’ve got a real obesity problem in the U.S.

We have a child happiness problem in the U.S. I talk about this in my book. Of the 29 industrialized nations, the U.S. ranks 26th on unhappiness. Our children are unhappy because our parents are not even participating in their lives because we’re all about work and we’ve really lost this sort of bigger life where you have healthy relationships, you have your health itself. It’s just all about work now.

Roger Dooley: Is your concept really just for knowledge workers? It seems like in the manufacturing environment or in some kind of repetitive clerical environment like a call center worker or a bank teller that the output per employee is largely governed by external factors and not something that they can say, “Well, I’m going to get a day’s work done in five hours instead of eight.” Is it practical in these non-knowledge worker type areas?

Stephan Aarstol: Well, we’re doing it in our entire company. Our company is an ecommerce company. We have a call center. We have a physical store. We have a warehouse and shipping people. So there’s all different types of jobs. We’ve got our marketing people and business people. We did it across the whole thing because we actually think productivity has changed in all of these areas. Software in our warehouse has changed stuff.

The fact that we have a website that goes 24 hours a day, we can help people with their customer service sort of self-serve. There’s voicemail. There’s email. There’s all of this different stuff that wasn’t available 20 year ago that customer service needed to work eight hours to get that done. So we changed everything to five hours and there has been no downside. In fact, there’s been an upside because this is the thing that people don’t really realize when I talk about the five-hour workday. They think, “Okay, he’s just saying let’s get a better work-life balance. Kumbaya, that will make us all happier.”

But by putting time constraints on stuff, it forces productivity. It forces you to find creative solutions. This is what is going on with three guys in a garage, a startup, that’s going against a 100-million-dollar company with 1,000 employees. If they go after a certain project, you can almost bet today on the three guys in their garage will win. The reason for this is because they have a severe constraint on money, for one, and also time. So they have to figure out creative solutions or they die.

When they do figure out those creative solutions that are forced upon them by these artificial constraints they have on them, that becomes a competitive advantage and they end up upending the larger company, the corporation, that is well funded and has an unlimited amount of time on that. If you take that extreme out further, you have government at the very extreme of that, where they have no budgets. They just have as many people as they want to throw. They just raise taxes if they want to spend more money.

So in the absence of constraints, you get wildly inefficient. That’s what we’re doing with this five-hour day is we’re putting this artificial constraint. Every day you’ve got that clock running and you’ve got to figure out how to get what used to take you 40 to 50 hours done in just five hours a day, and people figure it out. That’s what we found. We started it as a three-month test last summer but it worked so well we just continued with it.

Roger Dooley: I take it your customer service folks don’t staff the phones 24/7.

Stephan Aarstol: No, they staff them for 8:00 am to 1:00 pm. We reduced the hours. We put our reduced hours on the website and you know what happens? The same amount of people call in just a reduced hour. This is what happens with our store. People just come in at a wider click. We’re not a 7-Eleven. We’re not a convenience store. Just being open more does not necessarily translate into even better customer service.

When we’re there, we physically answer the phone. We haven’t gone to automated phone trees and stuff like this. We’re a very high customer service company and we’re a very high growth company. So what we’re trying to prove here is we’re going to build the biggest beach lifestyle company in the world and we’re going to do it five hours a day. Then everybody can say, “Well this obviously this works,” and we’re going to say, “Obviously you’re doing it wrong if you’re spending 50 to 60 hours in the office.” You’re basically just working very inefficient and there’s a better way.

Roger Dooley: I guess you can say that somebody like an airline might not find it quite as practical where they do have to have staff going 24/7. Saying, okay, we’re going to now have basically half as many people or something to do the same job would be kind of a burden because they probably wouldn’t be able to get the job done that much more quickly because it’s one of those things sort of governed by the workflow to some degree. I mean, you can still improve.

I guess another question would be—I get that you can use technology to increase productivity and offset some of the lost man-hours or person-hours but what about companies that have already fairly highly optimized their operations? In other words, they’re using the best software, they’re really exploiting technology as best they can. There’s not really a lot of room for improvement there necessarily, or is there?

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, I think there definitely is. Let’s take the airline because that’s a good scenario. So the people that are flying the plane and the stewardesses, those people have to work whatever hours that plane is in the air. They’re constrained to that. They can’t even leave the airplane. Like the police, fireman, a 7-Eleven, or maybe even like fast-food workers, there’s certain jobs that you’re actually not paid for productivity, you’re paid to occupy time, to fill time. Like you need police and firemen 24 hours a day. But in most jobs, you don’t.

If you look at the airline, their customer service reps or their agents at the desk or whatever, that’s much less so. If you take it into retail, like our company, we answer the phone but what’s the biggest retail innovation in the world right now, is Amazon. You can’t even call Amazon. So if you look at business how it’s always been done, you’re going to say, “We’re as efficient as we possibly can.”

If you start to put it in these time constraints, you say, “What can we actually take off the table and people won’t even miss it? It will force us to be better.” That’s what Amazon did. They just said, “We’re going to have a retail store and you won’t be able to get ahold of us by phone.”

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well actually I have called Amazon once or twice but the reason that they can do that, and they’re quite efficient when you do, but they make it so easy to do everything else on their website that there’s almost never a reason to call them. Calling up a company to ask a question or to place some kind of a transaction is actually pretty inefficient, at least from my standpoint. I would much prefer to click one button on the product and have it show up at my door a couple days later than calling somebody up and telling them who I am and where they should ship the darn thing.

So I think Amazon has really done a brilliant job in that respect. That is a good example where you might not be able to completely eliminate the 24/7 access but you could take tasks that had been performed by these people and automate them or shift them to the customer in a way that’s actually a positive.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, it’s leveraging technology. How can you leverage technology to make the human have to be there fewer hours? The other thing that’s happened is life has just gotten a lot cheaper because we have all of this automation. If you look at the food budgets, what people had to spend to basically feed themselves at the bare minimum. In the 60s, it was 20 percent of a person’s budget to just eat. Today, it’s three percent. So food has gotten really cheap.

If you look at electricity in the early 1900s, you’d have to work 15 minutes to light your house for an hour, to buy enough kerosene to light your house for an hour. Today, electricity is basically free. People don’t even think about the cost of flipping on a light. It’s near zero.

So all of life has gotten a lot cheaper and what we’ve done is we’re making more and more money, it’s getting cheaper and cheaper to live and where the society that thinks, “If I just make another $20,000 or $30,000 that’s going to make me happier.” In a lot of cultures around the world, that’s really where they are. Money is a scarcity. In the U.S., not so much.

Even people on welfare have flat screen TVs and smartphones. They have these basic nonessential things. So we’ve become this entire country where money is no longer a scarcity. The only scarcity is time. So that’s really what we’re doing with the five-hour workday is we’re saying, “You’re going to work 8:00 am to 1:00 pm.” You’re going to get off. So every day during the week, you’re going to have nine or ten hours of free time in a block. It’s going to be better than most people’s vacation weeks. Then you can do with that time what you want to do.

You can go make more money if you want. You can spend time with your kids. You can volunteer in your community. You can get in shape. Work on your relationships or just spend more time with people you love. You can do a lot of these things that actually were much more important in the world 1,000 years ago or at different times throughout humanity. Where today we’ve sort of pigeonholed ourselves into this it’s all about making money and working and then buying a bunch of crap that you really don’t need. It doesn’t make you happy.

Roger Dooley: I imagine the five-hour workday makes recruiting both easy in one sense but also interesting in another. I’m sure you must get some portion of the applicants who are primarily attracted by the fact that they would have to work fewer hours. Not because they’re motivated to work intensely in those hours but because, hey, five hours is better than eight.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, exactly. So this is a recruitment and retention strategy at its core. When Henry Ford changed the work hour to an eight-hour workday and doubled everybody’s wages, he did that because he wanted to get the best workers in his factory. The following month they had like tens of thousands of people lining up to get a job there.

When we did this, it’s like in the knowledge working world, and especially in our type of industry, we’re kind of on the cutting edge, we’re going to win or lose this war on our ability to attract the best talent. Bring in the smart people, let them do their things. So we want to give them a better deal.

We want to give the people—because in every office in America, there’s people that do just two to three times the work of everybody else in the office but they’re all held to this whatever hours you’ve got to work, that’s kind of how you’re measured. We want to attract all of those people that we know can work could work at this high clip and repel the other people. But you’re exactly right, we’ve all of a sudden attracted these two audiences.

When people apply to our company, and this is another way we’re efficient, is we require them to do video cover letters. So they’ve got to do a little two to three minute video on their iPhone, it just saves us from having to see so many people. We get basically an initial screening. We’ve got an initial project.

We get two types of people. We get people like the slob on the couch that is just like, “Oh, five hours, that sounds great. Why didn’t somebody think of this a long time ago?” Then you get the very high-performing people that sort of see this, “Wow, I could do this 8:00 am to 1:00 pm, work this job, knock it out of the park for them. I could start a business on the side. I can do whatever I want on the side because I know I can produce in five hours what most people produce in three days.” Those are the type of people that we keep at Tower, and the rest of the people we fire.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I guess also evaluating your current employees is really important because usually if there’s maybe not the best fit with the employee, they’ll often self-select themselves out of it and try for something that’s more their liking, but who else is going to offer a five-hour workday, at least at this point. As a result, you probably get people sticking around who might not be all that happy so then I suppose you have to be proactive about things and weed those folks out.

Stephan Aarstol: Yeah, and a few people have left since we’ve done it because there is pressure to perform. It’s like if you’re not performing and you check out at 1:00, you’ve still got a problem. It’s not like you can instantly just move your hours and all of a sudden you’re producing the same. You’ve got to figure out ways to cut out the waste, cut out the Facebook, cut out the online shopping, cut out the fantasy football, whatever people are doing at work today to fill their time—and there’s a huge amount of waste in corporate America.

Anybody that’s honest will tell you, they’re honestly getting two to three hours of work done in that eight hour day. They come into the office, they make themselves some breakfast, they go have some coffee, they check their Facebook. It’s a ridiculous workday because we are so productive now. We can get away with it. The bosses are not complaining because productivity in a larger scale is off the charts. People are working at a slower pace but productivity numbers are way up just because people are able to be much more productive today.

Roger Dooley: Stephan, one key to working a five-hour day is being really productive. I’m wondering if you have some productivity hacks that you use and would recommend to our listeners?

Stephan Aarstol: There’s a site for the book called fivehourworkday.com. If you go on there, you can enter your email and you can download the first 50 pages of the book for free. Then you can also, you’ll get, it’s about a 30 to 40-page pdf that goes over, it’s like 35 or 36 productivity tools that we use in Tower, sort of the secret sauce that allows us to work this compressed workday and be in 2014 we were named the fastest growing company in San Diego, as a surf company with five people doing five million dollars in revenue. These are the tools that we use.

There’s tools in there that have been around for a decade that are literally worth a million dollars to some companies and that are free to use and people are just oblivious that these tools exist. Because I’ve been in the startup world and I’ve had these constraints, we’ve been forced to identify these tools and use these tools. These are the tools that most of corporate America is just not using because they don’t have to, but these are the tools that are our competitive advantage. So anybody can go take a look at those. You can really ramp up what you can accomplish in a day by using those.

Roger Dooley: Great, well Stephan, I just looked at my watch and I see I’m already well past my five-hour mark. So, I’m going to have to call it a day here shortly. I’ll remind our listeners that we’re speaking to Stephan Aarstol, author of the new book The Five-Hour Workday: Live Differently, Unlock Productivity, and Find Happiness. Stephan, where else can our listeners find your content online? Are you on social media?

Stephan Aarstol: Sure, yeah. Our main website for our company—the fivehourworkday.com is just for the book—our website for the paddle board company is towerpaddleboards.com. Then we also have a beach lifestyle magazine which sort of tells you how to live this extraordinary life once you’re only working five hours a day, what are you going to do with the rest of your time? That’s at tower.life. Then you can reach me on Twitter @stephanaarstol.

Roger Dooley: Great. We’ll have links to all those places, to the Five Hour book itself and any other resources we talked about on this show on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Stephan, thanks for being on the show.

Stephan Aarstol: Roger, it was my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.