According to our guest this week, you’re better off adapting to the future as it hurtles toward you rather than trying to predict it.

Roland Smart has experience with entrepreneurship and business in ventures both large and small. While he now works for tech-industry giant Oracle, he has spent most of his career working for start-ups and having odd entrepreneurial adventures.

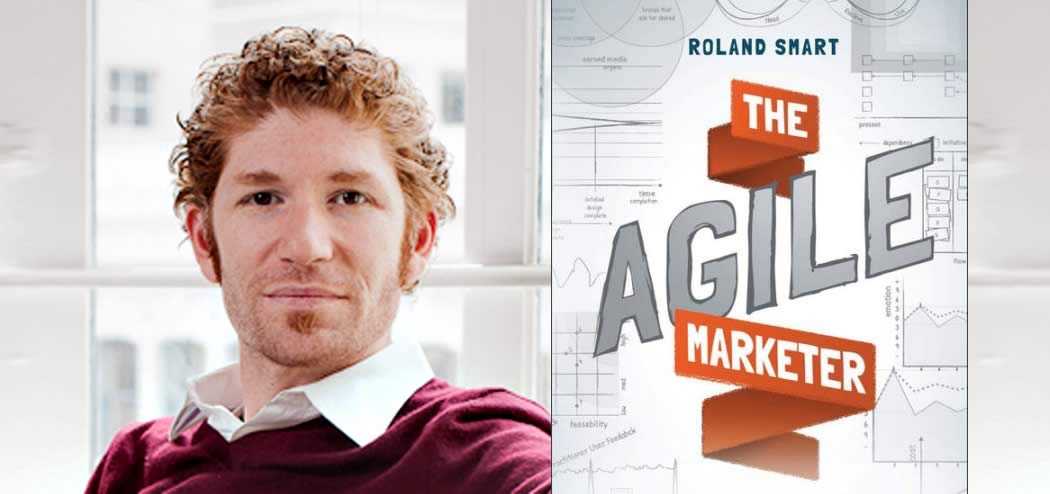

Roland is the author of The Agile Marketer: Turning Customer Experience Into Your Competitive Advantage, which dissects the fundamentally changed world of marketing in the digital age. The book and the man himself are both chock-full of advice about how marketers can update their thinking about the field to match its rapidly changing landscape.

In this conversation, Roland and I discuss his seemingly career-unrelated college major, his design for a portable bike rack, and how he did in school — and that’s just the first five minutes. We also talk in depth about the Agile approach and how Roland and others have applied it to their marketing to keep up with the breakneck pace of product development (and launch) in this era of über-connectivity. We wrap up with how you can start to apply Agile thinking to your own business or solopreneurship.

Roland Smart is the VP of Social & Community Marketing at Oracle, where he oversees programs that enrich communities tied to Oracle’s products and services. He previously held positions at a number of start-ups, where he witnessed the Agile effect firsthand.

He is also the co-host of the Marketing Agility Podcast and speaks at industry events like the ad:tech Modern Marketing Experience, The Social Media Optimization Conference, and SXSW. He has also written on tech and marketing for publications including Forbes and iMedia.

Roland’s unmatched experience with social marketing at Oracle and smaller ventures makes him a veritable expert in this field, so don’t miss this chance to hear from this industry leader.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why marketers aren’t good at predicting the future and how to work around this limitation.

- Why designs should be shown to customers even before they go into production.

- The importance of shifting our thinking away from the concept of marketing campaigns as having a beginning, middle, and end.

- Why marketers should start with a less prescriptive approach to marketing than Kanban or Agile.

- Why it’s crucial to eliminate negative peaks in customer experiences that can occur with your products and services.

Key Resources for Roland Smart:

- Connect with Roland: RolandSmart.com | The Marketing Agility Podcast | Twitter

- Amazon: The Agile Marketer: Turning Customer Experience Into Your Competitive Advantage

- Kindle: The Agile Marketer: Turning Customer Experience Into Your Competitive Advantage

- Magic Math: You Can Double Your Results in 43 Days

- Ep #115: How To Increase Your Visual IQ with Amy Herman

- QuickRak

- The Agile Manifesto

- The Agile Marketing Manifesto

- What is Kanban?

- Daniel Kahneman – Nobel Prize Winning Economist

- NetPromoter on Wikipedia

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week brings an interesting perspective to the show. Roland Smart is VP of Social and Community Marketing at Oracle, a huge company that most often works with other large companies. But a few years ago, he co-founded an entrepreneurial venture, QuickRak. QuickRak was a design for a portable bike rack that could be carried on a bike and deployed when attaching to a car was needed. So Roland has been involved both in the large enterprise and very small business camps.

Roland is a fellow Forbes contributor and a fellow Wiley author. His new book is The Agile Marketer: Turning Customer Experience Into Your Competitive Advantage. Thanks for being on the show, Roland. Welcome.

Roland Smart: Hey, thanks. Very happy to be here.

Roger Dooley: Great, I’m happy too, in part because I’m a community guy myself. I’ve been involved in a variety of online communities as an admin, a founder, a community builder. I know some of the challenges that you face in your day job at least. Do you work with multiple communities at Oracle?

Roland Smart: I do indeed. I look after something called the Oracle Technology Network. That is really an umbrella organization that supports pretty much every line of business across the company that sees community as integral to the success of their solution area. We support pretty much every product that you’re familiar with from Oracle, in addition to the Oracle Partner Network, our user group community, our paid support community, and a few others to boot. Yes, we have many, many internal stakeholders that we work with.

Roger Dooley: Sounds like fun. I assume these communities go beyond the digital world and actually extend to in-person events and so on.

Roland Smart: Absolutely. My team certainly oversees the digital experience but we also run programs in the real world, whether that’s events, programs, participation in third party events, hackathons, and all sorts of other things that we do to engage our community and extend the relationships that we have built online with them.

Roger Dooley: Great. Before we go any farther, I’ve got a really off-the-wall question. Did you get good grades in school?

Roland Smart: I got fair grades in school. I was one of those people who was maybe a little bit idealistic when I was in college. Reality didn’t fully sink in until I graduated from college. To be frank, I…

Roger Dooley: Better late than never.

Roland Smart: Yeah. In some ways I think it was a benefit to me, because to be frank I wasn’t that concerned with my grades. I was much more focused on the content and what I was learning. In some ways, I think, that may have caused me to be a little bit more entrepreneurial.

Roger Dooley: Actually really what you’re saying is it was more intrinsic motivation than extrinsic. That’s actually a good thing when you can generate it. I’ll tell you why I asked that, Roland. A lot of our listeners are quite interested in the psychological aspects of marketing and other things, and human behavior in general.

There’s a small body of research that shows people and their life outcomes are influenced by their names. One really crazy study showed that people with A and B names got better grades than people with C and D names and that kids named Lawrence are more likely to grow up to be lawyers, and so on.

I know there’s been a big replication crisis in social science research and some of this seems a little more out there than some. But supposedly, they did find these statistical differences. That’s why I asked. Thought maybe with a name like Smart, you might be a really high academic achiever. Or, kids rebel against their expectations too.

Roland Smart: I think what’s interesting is—and this is very true in community work that I do—is that when it comes to actually retaining information, people who do rote tasks well and allow them to perform well on a test that they’ve been taught to, actually don’t do a great job at retaining that content because they’ve learned it to take a test rather than learning it for the intrinsic reasons that they might bring to the course.

This is kind of what I was getting at with my last statement is just that maybe one benefit is that while I may not have done super well on a test, I think the fact that I was focused on and paying attention to the stuff that I really genuinely cared about, hopefully, maybe, had an impact on my ability to retain that information.

Roger Dooley: It seems like it served you well. You were an art history major, right?

Roland Smart: I was, although, art history is a little bit misleading, because I was an art history major but I focused really on the history of the art business—the museum business and the gallery business. It certainly was art history, but I’m not the kind of person who could speak at length about a particular period or a particular movement in the art world. I can tell you much more about how the art business really became a business and how it evolved from its roots.

Roger Dooley: Darn, well there goes the rest of my planned questioning. We’ll have to shift gears and switch from the Old Masters to some other topic. Actually, believe it or not, you’re the second art history person that I’ve had on in just a few weeks. The other was Amy Herman, she wrote a book called How to Increase Your Visual IQ, and I think she stayed a little bit closer to the field. She uses classic art as a way of teaching people like the FBI and Navy SEALs to be more observant, another interesting application. Between the two of you, you guys are really representing well for liberal arts education.

Roland Smart: Thanks. I have to tell you that not too long ago, I have a degree from Tufts and a degree from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I very recently in San Francisco got together with some alumni from the Museum School, the SMFA. I was surprised—of course, I shouldn’t have been so surprised in San Francisco—but of the ten people who were in the room, I don’t think that there was anybody in the room who was actually working as a practicing artist.

Though there were a couple designers. They were working as very senior designers at companies like Apple and Google and the rest of the crew were very senior marketers and startup people. I just think it’s fascinating that this group of people who have a very creative background have made their way into the tech world in San Francisco and been very very successful.

There’s something about studying design and studying art which I think sets folks up well for being effective and very productive in a very fast-moving technology-oriented business world.

Roger Dooley: Interesting observation. I’ll ask you one more slightly off-the-wall question. It’s about QuickRak. You’ve applied for a patent on this bicycle rack invention. That’s probably something else that relatively few art history grads can boast of. What happened with that effort?

Roland Smart: I started the company with a very good friend of mine basically because we had a problem that there was not a product in the marketplace to solve the need. So we created QuickRak to solve that problem. Basically the issue was that we might bike…

Roger Dooley: Classic marketing there, Roland.

Roland Smart: Exactly.

Roger Dooley: Discover the need, and fill it.

Roland Smart: Product/market fit, right? We found ourselves biking to work and sometimes having a drink after work. Living in San Francisco, the prospect of being intoxicated and riding your bike up a series of very steep hills, sometimes the motivation just wasn’t there to do it. But if we had a portable bike rack with us, we’d be able to get our bikes onto somebody else’s car or onto a taxi or onto an Uber. We decided we’d create that product.

I should also say I’ve been involved with many entrepreneurial ventures. I spent most of my career in the startup world, in the social technology space mostly, but also I worked for a CPG company as well that brought me to San Francisco. So this was something very, very small that I did to solve a problem that we actually had.

What is interesting is that when we built this product, and it worked great for us, but what we found was that it was actually a device that people had a pretty hard time using. We never got the device to a place where we felt it was ready for the mass market. Also, our regular life got in the way of us pushing too much harder on it.

One thing that is interesting though, is that we stopped actually actively working on the effort a couple years ago but both my partner and I still get regular inquiries about it and people want to use it. We have some friends who actually do have them and who are savvy enough and maybe engineering-oriented enough to use them and make them work for them. I of course use one myself.

Roger Dooley: Just have to work on the user interface a little bit.

Roland Smart: Believe me, we spent a lot of time working on the user interface. We would love to continue that work when we have more bandwidth but we did invest a lot of time. We couldn’t get it to the place where more than 50 percent of our test users could get it right on their first try. We really felt like we needed to get beyond a threshold like that to be able to…

Roger Dooley: Well, yeah, the returns, and dissatisfaction, bad reviews, and so on, if you had those kinds of numbers.

Roland Smart: Totally. But it is a good example of where we applied Agile in our own work. Before we even started working on this project really in earnest, we invested just a little bit of money in advertising and a little bit of money in a very, very basic website that made it appear as if this product already existed.

What we saw very quickly was that there was real validation from the market that if we could build this product that there was an opportunity in the marketplace for it. There was room for it. We did some other things, we partnered with some bike shops where they let us come into the bike shop and do demos and talk to people who were in the context of a bike store.

We even went to some biking events to present it, a prototype of it, to continue that validation. Each step we took indicated to us that we should continue investing. That’s kind of a central idea to Agile, right?

Roger Dooley: Right. Roland, that’s a good transition. I know I’ve had a little bit of exposure to Agile in the software development sense and your basic premise is applying some of these techniques to marketing, but for our listeners who haven’t been exposed to it or even have limited exposure like I do, why don’t you explain the origin of the term and what it means and so on?

Roland Smart: Sure, so Agile really comes out of the software development world. About 17 years ago, a bunch of very influential software developers got together and wrote something called the Agile Manifesto. It outlines a set of values and a set of principles which guide the way that software development could be done. It really represented a very different approach to software development than the traditional way that it had been done.

This new approach that they articulated was so popular that in a relatively short period of time, it really revolutionized the way that software development was done. Now today, Agile is really the dominant practice for software development. As an approach, Agile basically, it’s a philosophy. The philosophy sort of acknowledges that we are not very good at predicting the future and that one way to deal with that is to put out something small, validate that you’re headed in the right direction, or that you’re not headed in the right direction, and pivot as necessary and zero in on product/market fit.

This is an alternative to the traditional waterfall method, which if you know where you’re headed—exactly where you’re headed—waterfall is a great approach because it can be highly efficient. You can do the traditional Gantt chart. You can map out exactly what the steps are. You can line them all up in what I would call the “measure twice cut once” approach and work very efficiently. The problem is, of course, with software development and the rate that things are evolving today, it’s nearly impossible for businesses to predict the future.

Roger Dooley: Just to clarify, by waterfall you mean more or less a fixed, rigid, schedule and organization for any given project or activity where the activities are fairly predictable, their durations are predictable, and their outcomes are more or less predictable.

Roland Smart: Yes. So something that would be characteristic of waterfall, imagine that you’re building a building. That is something where if you get halfway through the project and you want to change the design of the building, it’s exceptionally expensive to do that because you’ve actually put in foundation and you’ve put in this stuff which you might have to rip out and which is very costly.

So waterfall is characterized by—the word waterfall comes from this idea of handing off. It starts with research design and design and when they’re done, they basically stop work and hand off to development, or in the context of a building, somebody who’s going to actually start building, the contractor. When the contractor is done, it gets inspected. When it’s done being inspected and passes, people get to move in.

But if you during the inspection phase find something that isn’t right with the building in the waterfall process, going back to the beginning, as I said, is extremely expensive. So that’s why for something like a building, waterfall can be a good fit but you have to be really committed to the design you make up front. That’s why it’s so important to sort of measure twice and cut once.

In the context of something like software, we have all these ideas about what we think it should be or how we think it’s going to work or how we think people are going to use it. But really, we don’t know. Most of the time we actually aren’t great at predicting the way that people are going to use it. So we need a much more flexible approach that allows us to embrace the unknown and respond to the unknown and respond to unanticipated insights and opportunities that we come up against.

Now, what I talked about thus far is really primarily focused on the software context, right? So how does everything I just said relate to marketing? If you think about a company where you’ve got product management operating in an Agile fashion but you’ve got the marketing organization using the traditional approach, waterfall, what you’ll see is that these two groups are going to quickly get out of sync and it’s going to get very frustrating. You’ve got product management iterating on a monthly basis, and they see opportunities that take them in a different direction.

But marketing is working on this—they’ve got their annual marketing plan or their six-month marketing plan, and they get ready for their big thing at the end of the six months but the product team has gone in a completely different direction. There’s just this disconnect that’s incredibly frustrating and it doesn’t work for either party. So product management has gone through a revolution in the way that they do their work. Marketing has not gone through a complementary modernization to the way that they work. That is leading to a big disconnect.

So marketers are accepting a lot of influence from product management. We’re really taking a page from their book. There’s a couple reasons why that’s happening. One, marketers are managing more software than ever before and Agile is the best practice for doing that. So that’s kind of a no-brainer. But the other reason has to do with some of what I just described about how do you keep marketing and product management in sync?

It turns out that a lot of the work that marketers do, taking an Agile approach is very appropriate and allows them to stay in sync with product management. That opens up all sorts of interesting new opportunities to do things like bake marketing directly into the product so that you really blur the boundary between what is the product and what is the marketing.

Roger Dooley: Let me stop you for just a second, Roland. I’m wondering if maybe my Agile experience is different but when I’ve seen it applied primarily on the software side, even if it was very much user-facing software, the customer, the user, really wasn’t very much a part of that Agile process.

Rather, it seemed to be just a way of sort of chunking a big project down into pieces because obviously as you alluded to, the time required to perform some of these acts is often variable. So it’s something that to lay out an entire timeline for a project is tough. This enabled shorter checkpoints and things to be adapted on the fly based on progress and what the developers found.

But really, it was conducted more or less in isolation. Really what you’re saying is that shouldn’t be the case. There should be those checkpoints and waypoints should be a way to make sure that the effectiveness of the product from the user’s standpoint or the customer’s standpoint is there.

Roland Smart: Yeah, if that’s the way that it’s being implemented, then it’s not consistent with the Agile Manifesto and the values and principles. I think that those values and principles are very much about putting the user at the center of the process.

In other words, it’s not so much challenging to lay out these plans. You can do that. The challenging part is that the plans that you make are wrong. They’re wrong because they’re based on a set of assumptions that you have about the way that people are going to engage with your campaign or your product or your service or what have you.

Agile thrives on feedback. As a community marketer, part of the reason why I care so much about Agile is that to run an Agile project, you really need a very tight connection with the community, or at least metrics or analytics that you get from that community through your product or service or platform or what have you.

Roger Dooley: Ronald, why don’t you use a real world example of that so our listeners can visualize how that might work in their project or a project?

Roland Smart: Sure. As one example of this, my team has a community platform that we make available to lines of business inside of Oracle but it’s obviously available to anybody in the Oracle community who wants to come and engage with us or engage with their peers. That platform is one that we are constantly investing in, constantly improving. We have a set of ideas about how we think it should be improved.

We also have a space on the platform where our community can tell us what they’d like to see, how they’d like to see it improved. They can give us feedback on the ideas that we have about how it would be improved. We have the ability to develop some of these things and show them to a user before we push it into production and to get their feedback. That’s how we validate that we’re heading in the right direction and making each incremental investment that we make is correct before investing and deploying it.

So it’s not about having this year-long strategic plan that encompasses this entire roadmap that we’re laying out in advance. We have strategic visions about where the platform is going and at regular cadences, quarterly, we try and align that with what the team, the Agile team, is working on when it comes to the immediate feedback that they’re getting from the community on, “Hey, we want to do this. Is this good or not good?” That’s what’s driving the day-to-day pivots that are helping us zero in on the best possible experience for our users.

Roger Dooley: How much of the information that you get is that user feedback of “Wow, this is great,” or “This sucks?” Or compare that to metrics where you might have community involvement metrics like number of visits, number of active community members, number of posts, you know, whatever. Do you use both?

Roland Smart: Yeah, absolutely, we use both. When I talk about getting feedback from the community I’m not just talking about the stuff that they expressly communicate to us. I am talking about the stuff, their actual behavior that we’re watching with web analytics and the analytics we have through our own platforms.

So absolutely, it’s both of those things. The project in question, whatever the initiative is, will sort of determine how much we’re going to rely on each one of those channels. So in some cases we do have to rely more on the feedback that we take directly. In other cases, we can rely much more on the web analytics.

Roger Dooley: A key part of at least some Agile processes is the concept of Scrum. Quickly, how would you describe that to the folks that may not be familiar with that?

Roland Smart: Agile is an approach, Scrum is a method. Which means that it’s, a method is something that you actually use to implement the approach. But really, methods themselves are just a collection of underlying practices. It’s kind of like a hierarchy of terms that I just laid out there. Agile is the approach or the philosophy. The method is just the collection of practices that you’re bundling together.

Then at the bottom level there’s just like 100+ Agile practices. Those practices include things like scoping your backlog or what we call grooming. The retrospective, the sprint planning meeting, planning poker is a way of estimating stories in your backlog. These are all things that I would describe as specific practices.

So Scrum as a method tends to be medium in terms of its prescriptiveness. It has a pretty significant amount of underlying practices baked into it and it’s a pretty rigorous framework. It’s a method that you see deployed a lot in the context of development.

For marketers, starting with Scrum is usually too prescriptive. I recommend that marketers start with a method that has less underlying practices and that’s less prescriptive in general. Kanban is a good example of that. Kanban actually comes out of the manufacturing world, not the software world. There’s kind of a convergence that’s taking place between lean, which is this tradition that came out of manufacturing, and Agile, which came out of the software world. There’s just a lot of shared DNA between those two things.

The Kanban method happens to come out of the lean tradition and manufacturing. Scrum comes a little bit more out of the software development world. I don’t know how deep you want to get into these but a couple of the key things that differentiate them, Scrum prescribes some roles on the team, like a Scrum Master. It also tends to rely on time-boxed releases. So a commitment to release something on a very regular cadence, whereas Kanban is more about managing work through design, development, and release. It tends to put a work in process limit. It constrains the number of things that can be in each one of the stages at any one time.

So the methods are a little bit different because they embrace different underlying practices. As I said, I generally advise that marketers start on the less prescriptive side with Kanban. They can always add practices and sort of move towards Kanban over time. In fact, many marketers use something called Scrumban which is a combination of the Scrum and Kanban method.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I can see where the Scrum approach might add a little bit too much structure. I know when I was introduced to it briefly, that was really my first exposure to the concept of Agile. After hearing the explanation of how the Scrum process worked I was thinking, gee, that doesn’t sound very agile at all to me. Kanban on the other hand, I think is something that our listeners can identify with. That’s partly a process of continuous improvement.

In fact, last year I did a post on my Neuromarketing blog about how you can double your results in about a month and a half or so. It was not all about Kanban but how small incremental improvements can add up. I think the philosophy too, like you talk about a community platform, I think that some folks given the option say, “Okay, we really want to improve the involvement of our community members.” People aren’t staying. They aren’t joining, or they’re not returning.

One approach would be to say let’s redesign this thing from the ground up and make the ultimate community platform and send a bunch of developers away for a year or two to do that. But the alternative approach that is faster and probably more effective in the long run is to try and make a series of small improvements, measure those results, and just keep going making these little tweaks. It’s amazing how you stack a bunch of one or two percent tweaks on top of each other and pretty soon you’ve got some really good numbers going.

Roland Smart: Absolutely. I mean that’s what Agile is really all about. I think underneath that, it does require a mindset change on the part of the marketer in so far as we need to move away from a world in which we think about campaigns that have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

We need to move towards a world in which we see the things that we’re investing in much more as programs or as our products and services. So things that we’re going to be investing in on an ongoing basis, things that are always on, things that are always spinning off value and that we’re optimizing and making better and better and better over time.

That’s a very different approach than the traditional approach that many marketers are used to and that what I’m describing. Taking this programmatic approach really lends itself to working in an Agile context. Whereas that other campaign-oriented workstyle is much more oriented to the waterfall approach.

Roger Dooley: One of your things is user experience. How would you apply the Agile approach to improve the user experience, either on a website or in a process of some kind?

Roland Smart: This is a very big topic. This is something that I talk at length about in my book and how to apply Agile in the context of customer experience. I think there’s—I’m just trying to think where to best jump in here. Fundamentally, I think the approach is really appropriate for thinking about CX because if you think about CX, CX is something that does not have a beginning, a middle, and an end. CX is something that is always going to persist for your customer.

There is a customer lifecycle. Because of that, I think you can identify points in that journey and start iterating on how do I make this touchpoint more successful or more productive or a better experience for a particular user. At a very high level, when I talk about customer experience, I talk about job number one should be about eliminating negative peak experiences. Peak experiences that are going to do long-term damage to your brand. Taking an iterative approach to turning those bad experiences into at least adequate experiences.

I think the next step is generally to look for ways to simplify experience and consolidate experiences across the customer lifecycle. The last piece is about finding opportunities where you can deliver a truly great experience or what I call a peak experience. This is sort of based on the work of a Nobel Prize winning economist named Daniel Kahneman who developed something called the Peak-end rule which basically he tried to understand how do people think, reflect back, on an experience that they had. What really has an impact on the impression?

It turns out that marketers, I think, traditionally have looked at customer experience across let’s say an episode. They would take the average of the experience at each of the touchpoints in that episode and then they would use that average as a proxy for what was the overall customer experience.

But in fact, what Daniel Kahneman points out in his research is that really there’s two points which are much more important than any other points. That’s the peak experience, whether that’s a good experience or a bad experience, and the very last experience that you had.

This is why negative peaks are so important to get rid of because if you have negative peak it has a very long term and distorting negative impact on the way that your customers think and feel about your company or brand. So if you can deliver a positive peak experience, you can actually get away with having a lot of other experiences that are just adequate or just good.

Roger Dooley: So how do you identify those peak experiences, whether they’re good or bad, Roland?

Roland Smart: I think marketers have a lot of tools that they use to do it. I think the one that most marketers have heard of and which I see being implemented more and more is something like Net Promoter which you can deploy right after a user has had an experience and which gives you a good sense of whether that was a not good experience, a decent experience, or a great experience.

Roger Dooley: So basically you’re asking people?

Roland Smart: Yeah. I mean obviously you don’t have to ask everybody. You just need a representative sample.

Roger Dooley: Right, you’re basically relying on what folks tell you was either good or bad or exceptional one way or the other about their experience.

Roland Smart: Yeah, like I said, there’s a portfolio of different ways you can do this. This is I think one of the most reliable and commonly implemented approaches to understanding CX.

Roger Dooley: Right. I’m glad you brought up Kahneman because our listeners are very familiar with his System 1 and System 2 thinking split but the peak experience is less familiar. So I’m glad you’re able to bring that up.

A lot of what you talk about, Roland, sounds like sort of a big company type thing but earlier you talked about how to some degree you employed these Agile techniques in evaluating this sort of little micro-opportunity of an entrepreneurial idea that at that point was just that—an idea. It wasn’t a product yet. How can small organizations or even solopreneurs and so on apply some form of this thinking?

Roland Smart: Actually, I think Agile is much more of a small company thing than a big company thing. Its roots are in small companies, small entrepreneurial companies. Big companies are trying to embrace Agile and trying to figure out how to make Agile scale because they see the benefits that small companies have obtained through the use of Agile. Agile is actually I think easier to implement at smaller companies.

Now as I said, I spent most of my career at smaller startups and that’s the context in which I was introduced to Agile and the context in which I think I’ve seen Agile implementations be most successful. I think larger organizations certainly see the value and we see Agile making its way into larger organizations, but scaling Agile and having it be successful is really kind of where the rubber is hitting the road right now for those larger organizations.

A lot of smart marketers are trying to figure out how to get it to scale and work at big organizations like Oracle. So a portion of the conversations that I have on the Marketing Agility Podcast, which I cohost with Frank Days, focus on that topic. In terms of how small companies get started with Agile, I think there’s amazing resources that are coming to market right now. I think Agile is just getting a ton of traction with the market.

Obviously, I wrote a book about it to help people get started with it. I would recommend reading that book if some of the ideas that I’ve shared today are of interest and inspiring. But there is something called the Agile Marketing Manifesto which is out there and the reality is the Agile Manifesto was written for the software context. You can’t just take it from the software context and implement it in a one-to-one way in the marketing context.

We need to adapt it and interpret it for the marketing world and for the kinds of projects that we’re working on. So smart marketers got together and actually articulated a marketing-centric interpretation at AgileMarketingManifesto.org. I’d recommend checking that out. I would definitely spend a little time learning about the most common Agile methods that are being used by marketers. There is certainly some great blogs out there.

If you want to hear from marketers at small companies that are really in the trenches trying to implement Agile, we bring many of them on the Marketing Agility Podcast. You can hear from them firsthand, you don’t have to take my word for it or what I’ve written in my book. You can hear it directly from the people who are in the trenches trying to make it work.

Roger Dooley: Great. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Roland Smart whose new book is The Agile Marketer: Turning Customer Experience Into Your Competitive Advantage. Roland, where else, if anywhere, can our listeners find you and your content online?

Roland Smart: Certainly. I’d love for you to reach out to me on Twitter, it’s @rsmartly. I also write a blog myself at rolandsmart.com. You can learn more about my book there. Of course, I mentioned already the Agile Marketing Podcast which you can find on iTunes or your podcasting service of choice.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link to all those places, to your book, and to any other resources we talked about during the course of the show. Plus, we’ll have a text version of the conversation there too. Roland, thanks so much for being on.

Roland Smart: Thanks for the opportunity. I enjoyed it.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.