Just as customers are influenced by marketing, firms change their tactics in light of buyers’ responses. How might markets be influenced similarly, to reflect the people that drive them?

On this episode, I talk with Ray Fisman about how human behavior affects markets — which many of us think of as near-mystical, self-directing phenomena. In reality, markets are a product of our behavior, and Ray explains the modern economy in these terms.

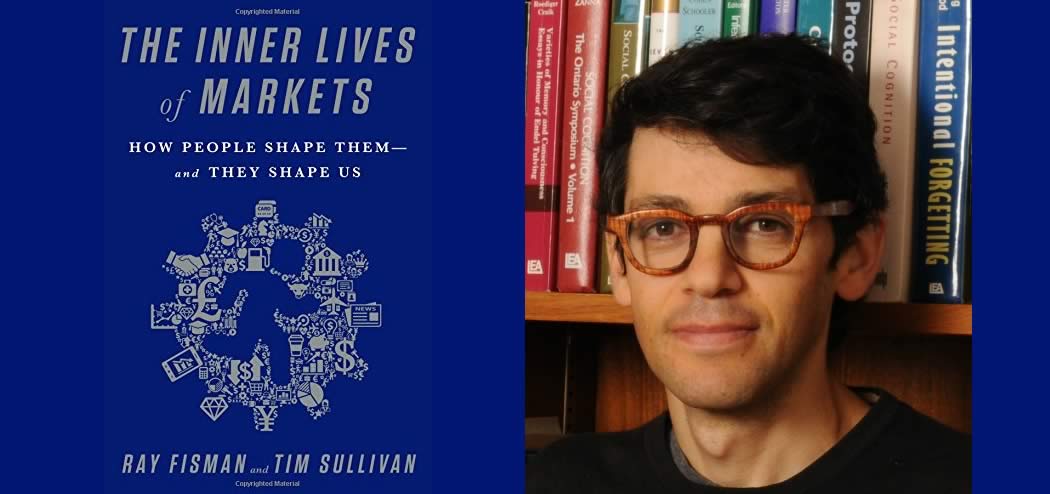

Ray is a behavioral economist with a knack for explaining economics in ways that relate to our everyday existence. In his new book, The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us, Ray and co-author Tim Sullivan turn complex economic concepts into easily understood prose.

Ray and I discuss his previous work with eBay, which illustrates how firms convey their trustworthiness to buyers and why bad firms won’t copy these tactics. Ray shares a couple of the techniques that firms use to convey their strength to competitors and customers alike.

We also touch on how marketplaces today are not as spontaneous as they once were — whether they are curated by sites like eBay, or directly influenced by the U.S. government, for example — and how this affects markets’ ability to accurately predict human needs.

Finally, we dive into how our thinking about markets has shifted over time, and how big firms continue to dominate markets even though they no longer follow the same successful templates of yesteryear’s firms.

Ray Fisman is a behavioral economics professor at Boston University. He received his Ph.D. in business economics from Harvard University in 1998 and spent the following year working on a manufacturing survey in Mozambique for the World Bank. Since then, he has dedicated his academic career to explaining the links between economic theory and everyday life, co-authoring The Org: The Underlying Logic of the Office and Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations.

One of Ray’s most-cited studies revealed that UN diplomats from countries perceived to be more corrupt tend get more parking tickets than diplomats from less corrupt countries. Studies like this show off Ray’s creativity and the wider applicability of economic thought.

Since behavioral economics has informed many developments in neuromarketing and behavioral psychology, Ray’s knowledge perfectly dovetails with what we explore each week on The Brainfluence Podcast.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How trustworthy firms signal their reliability to customers.

- Why markets are generally good at fulfilling human needs.

- Why companies might “burn” money, and what this signals to buyers.

- Why some jobs are advertised for “top-ten business school graduates only,” and whether this is effective hiring.

- Why market frictions are necessary for functional firms.

Key Resources for Ray Fisman:

- Connect with Ray: Twitter

- Hardcover: The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

- Kindle: The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them—And They Shape Us

- Kindle: The Org: The Underlying Logic of the Office

- Kindle: Economic Gangsters: Corruption, Violence, and the Poverty of Nations

- eBay

- Michael Spence: “Job Market Signaling”

- Ronald Coase

- Upwork

- Massey Energy

- Pets.com Final Superbowl Ad – 2000

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest today is Ray Fisman. He’s a professor in behavioral economics at Boston University. We don’t have that many economists on this show but the field of neuromarketing and behavioral psychology in general has been driven in part by the work done by behavioral economists.

Ray’s a prolific writer and the newest book he has coauthored is The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them and They Shape Us. Welcome to the show, Ray.

Ray Fisman: Thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley: I know that any number of our listeners on this show are involved with sales in some way. If they’re not directly in sales, they interface with it or manage it. The one stereotype of the unethical salesperson is the used car salesman. I guess I never thought much about why that same aura never developed around other parts of the sales profession but it turns out that economists, and George Akerlof in particular, have a logical and scientific explanation for that. What is that?

Ray Fisman: The story of the lemons market for cars is really a metaphor for any kind of market where one side knows more than the other. So it can be that the seller knows more than the buyer or the other way around. When I buy insurance for health care, I know a lot about the risks I take. I know whether I roller-skate if you like or skateboard to work or whether I just walk to my desk at home. So there are lots of cases where one side of the market is better informed.

One of the canonical cases in the reason why used car salesman has come to be a shorthand for shady business is because someone who has driven a car very often knows much more about whether that car is going to start two days after you’ve driven her off the lot than the buyer does. Akerlof’s point in writing this paper was not because he was interested in the used car market per se but he wanted to illustrate how a market can unravel completely when you have these so-called information asymmetries in a market.

So if you think about it in the following way, imagine as we often do in writing down economic models that there are only two types of people in the world: those that have well-functioning cars and those that have lemons. So, cherries and lemons. You have people who’d like to buy them and they’re willing to pay more for the cherries than for the lemons.

The problem comes up when the cherries can’t find some credible way of conveying to consumers that they’re the good type. So they’re lumped in with the lemons. So they’re only paid as much for the good cars as the lemon’s owners are for the bad cars. Here is the critical piece: the cherry sellers, the cherry owners, pull their products off the market. So by virtue of being lumped in with the bad type, the market quality deteriorates.

Now imagine that there’s a gradation of qualities. There are fantastic cars, which are hard to observe, there a liability, all the way down to cars that are worth absolutely nothing. If you end up pooling all of these together because you can’t distinguish among them, you initially get the very best cars self-selecting out of the market, but that lowers the price that people are willing to pay in this market. So you have more opt out and so on and so on and so on until the market falls apart. So this was Akerlof’s way of explaining how a little bit of information frictions can lead markets to fall apart completely.

Roger Dooley: So why even in his time, when he wrote that, why hadn’t the used car market fallen apart? Obviously people were still buying them and putting up with the salesman and the loud, plaid sports coat and so on.

Ray Fisman: Yeah, so this was the next iteration. The book is in a sense, in part, a history of how economists, how they’re thinking about markets have evolved over the last half century or so. Akerlof made this observation being full aware that used cars get bought and sold every day.

So along came Mike Spence, who was a student of Akerlof in a sense, wrote down kind of a description of how market participants salvage these markets through signaling. So the first iteration was how market asymmetries cause unraveling. The next was the ingenious signals that market participants come up with for making transactions go through nonetheless.

Some work that I’ve done, which I will I guess choose to advertise here in collaboration with eBay has been on how sellers can actually use charity as a way of signaling their reliability. The critical part, go back to the original Akerlof model, what makes the market unravel is that the good types don’t have a credible way of conveying to buyers that they’re reliable. This is the critical element to an effective signal. It has to be credible. Otherwise the bad types make the same claims.

One application of this, we look at transactions on eBay where you do have a credible way of signaling, we argue, that you’re a reliable seller, that’s by giving money to charity. The way to think about this, and I think it’s a nice illustration of how signals in an economic sense and in a market sense, work more broadly. It’s a nice illustration of the signaling model. So think about an eBay seller who’s willing to burn ten percent of revenues in order to see some social good done by giving money to Save the Children.

The type of seller who is willing to burn that ten percent in revenues is probably the type who also will suffer psychic distress if he cheats his customers. So what makes this signal credible, a purely avaricious greedy selfish seller, can’t copy the signal because he’s not willing to burn the ten percent in profits to see social good done. So he’s not willing for example to increase revenues by five percent to then turn around to give ten percent to charity. He still ends up with less money. But the generous seller is willing to do so. He’s willing to burn his own money to see social good done. This is what makes it credible as a way of separating reliable sellers from the cheats.

What’s intriguing is that we do observe that consumers are willing to pay more for charity-linked products, but furthermore, they only do so for sellers that don’t have long track records on eBay. If you’ve sold thousands of items and shown you’re reliable, you don’t need this other way of signaling your honesty.

It also turns out that consumers are right to make this inference because we have data on disputes registered by buyers against eBay sellers and it turns out the ones that sometimes put up charity listings are in fact more reliable. They generate about half as many customer disputes.

Roger Dooley: That’s interesting. It seems like that could be a strategy adopted by somebody who was an unethical seller simply to fleece people. I don’t know that Bernie Madoff was a big charity donor but it wouldn’t surprise me if he was, both as a means of attracting clients but also as a way of signaling how reliable and generous he was.

Ray Fisman: Yeah, but this is the critical piece of it. The signal has to be something that the so-called bad type doesn’t want to copy. So the good type, the generous type, the type who cares about his customers, is willing to give ten percent of his revenues to charity in order to get five percent more revenues because he got so much happiness from giving to charity. The bad type isn’t willing to do it because he’s still five percent down on net.

But your point I think more generally is a correct one, or is a reasonable one. That’s why we see every company making claims about their corporate goodness. Before the company disappeared from existence, I downloaded a copy of Massey Energy’s corporate citizenship report the year that the Big Upper Branch Mine exploded killing lots and lots of miners inside. So even a company that is obliterating the environment of West Virginia and killing its workers, still wants to make these claims about good citizenship.

Roger Dooley: But there is evidence that it does serve as a signal that people notice and it changes their behavior, so maybe it’s worth doing.

Ray Fisman: To the extent that your listenership is comprised in part of marketers, I think one has to be very careful with these sorts of claims because consumers also rightly respond quite negatively, at least in an eBay setting, which I don’t think is necessarily so peculiar, respond very negatively to unverifiable claims. In other work, we look at what happens when sellers put up listings which aren’t done through formal channels, which just say, “Oh, I’m going to give money to Katrina victims.”

Roger Dooley: Right.

Ray Fisman: Buyers respond very negatively to this. The sales rate is far lower than for similar items where there’s no charity connection whatsoever. I think there’s an important message in that.

Roger Dooley: Right. In that case, eBay itself is the mechanism for distributing those charitable funds, right, or for collecting them, so you know that it’s going to happen. As opposed to somebody just saying, “Oh yeah, we’re going to give money to charity.”

Actually though, I think that for marketers they often use all kinds of signals to show that they’re reliable. They will show that they are a member of the Better Business Bureau, they will put other trust symbols on their website. They may show a photo of their owner. They may show a picture of their building or their employees. All of these things I think are trying to signal that we’re for real. We’re not somebody operating out of a cubby-hole in a basement that isn’t really reliable.

Ray Fisman: I think these issues are extremely interesting at this particular moment in time, precisely because we have so many new quality verification mechanisms arising online. In other work with eBay, we’ve looked at more standard quality verification mechanisms related to like power seller status, etc. These are very powerful in attracting both higher sales but also higher selling prices for eBay sellers. It’s also, in the wild west of commerce, these issues are also particularly important.

I have a friend who has a graduate student who’s doing work on quality verification mechanisms for powered milk in China. There it’s not just a matter of doing better business, it’s a genuine public health issue. So maybe this is one way of getting to the point that markets really are very good and very important for fulfilling human needs but very often you need the sort of oversight and curation.

That really is one of the main points of the book, is that markets have gone from being much more spontaneously generated to being very carefully curated and managed, whether by a platform such as eBay or Uber or others, or very deliberately designed as in when the U.S. government decides it wants to sell more wireless spectrum. They don’t pick some auction mechanism at random. These are very carefully designed marketplaces.

Roger Dooley: I think that signaling is interesting. You have a maybe not exactly amusing story about the fellow who had the gang tattoo and ended up paying the price with his life for having it visible on his face. On the other hand, when you do tattoo your face, it really shows commitment to whatever cause you have tattooed there. It may give you benefits within the gang but might be kind of a handicap outside that environment, whether you’re talking to a policeman or a rival gang member or somebody else.

Higher ed is something that has been an interest of mine for quite a while and recruiting and specifying top ten business school grads only. You know, at first, you look at that and say, “Well, that’s really kind of a stupid thing to say because we all know that smart people don’t all go to top ten business schools, that other schools have a distribution of very smart people too. So why would a company do this?” But there is kind of some rational behind that, right?

Ray Fisman: I guess I’m going to say yes and no. I’ll tell you first of all the textbook case, which is what we have in the book. Then I’ll maybe say a little more about what I actually think. The textbook case is essentially that Harvard Business School’s Admissions Office is doing essentially a screening job for Goldman Sachs and McKinsey and others.

If you like, a Harvard undergrad degree, all it’s showing employers is that you have the ability and willingness to stick your nose to the grindstone and work your way through the rigor that Harvard throws at you. And someone who isn’t going to be a fantastic consultant or investment banker doesn’t have the aptitude or the stick-with-it-ness if you like to make it through such a rigorous program. So that would be a classic version of the Mike Spence signaling model, which was focused in fact on higher education as a labor market signal.

I can’t help mentioning another take on this and talking about labor market signaling which comes from a friend of mine who was in fact a finance professor at a top ten business school and has recently moved to a large investment management firm. What this friend of mine told me is that for the sales positions they tend to higher exclusively out of places like Harvard Business School, Columbia Business School, because that somehow serves as a signal of prestige to clients.

Whereas the people who are actually managing the operation of this firm, they will take the very best students from SUNY Buffalo because these are students, there’s no sense of entitlement in the student population, they are the ones who are actually willing to put their nose to the grindstone and really show their worth rather than expecting that everything be handed to them. So that in a way turns the signaling model on its head.

Roger Dooley: Right, not that we would want to characterize all Harvard grads as being entitled jerks, but I think…

Ray Fisman: No.

Roger Dooley: But there is I think a general sense that when you graduate from a super elite school that opportunities will be presented to you, so that is maybe a little bit different mindset than somebody has coming out of a second tier school.

Ray Fisman: I don’t think Mike Spence would disagree with this. He would say there’s some signal component. But if it were pure signal, then it would be astounding that these top tier universities have maintained their positions for so many years if their value added were zero. Because really, then you should just be able to devise a test and have a testing firm that does exactly the same thing. And yeah, we are seeing a little bit of this.

I don’t know really about the North American market, but there’s an Indian company called Aspiring Minds which provides testing services for companies like Google that really allows them to extend the set of prospective employees that they can consider well beyond the Indian Institutes of Technology, the elite institutions, to lower-tiered schools because the students from those lower-tiered schools can show they’re great programmers by performing highly on this test, not just by getting into an elite college four years before they even apply for the job. So this is again a case where we may see that technology actually changes how we think of some of these classic models.

Roger Dooley: Right. It’s really interesting. While we’re on signaling, one other signal that you mention is money burning and how companies will sometimes burn money. What do you mean by that?

Ray Fisman: If you think about a company that expects to be gone tomorrow, would you really want to take your last million dollars, tow it out to the middle of a football field and light it on fire? No. You just take the million dollars and shut the business down. So it’s like a signal of longevity.

The only type of company that’s willing to burn money, whether by torching it or having some information content-free advertisement in the Super Bowl, which is another very visible form of money burning, the only type of company that will do that is one that expects to be in it for the long haul or relatedly, has enormous financial resources. Those are the types of companies that are willing to advertise in the Super Bowl. So you can think about it as partly informing consumers but partly just about signaling that you’re a strong firm.

Roger Dooley: Probably most of the time it works, maybe not so much for Pets.com. You mention their experience in the book where they ran this really stupid commercial that said, “We just wasted three million” or something on this ad and in fact may have been the right signal but then they did actually go bust.

Is this sort of a peacock effect, putting it more at a human scale, where of course a male peacock shows that he’s super healthy and well fed by having this giant and totally pointless display of tail feathers. Then humans sort of perform that same ritual by conspicuous spending to show that I’m essentially very fit. Typically, in the case of men, spending or donating. In the case of women sometimes, offering time as volunteers and so on. But all of these are sort of demonstrations of fitness. Is that really what’s happening at a corporate level?

Ray Fisman: Yeah, I think the peacock metaphor is perfect. I think that’s exactly right because if you could get away with not having these biologically taxing feathers and just get yourself the best mate, you would do so and you would save yourself a lot of time and energy. But it’s the only way that you can credibly signal to others that you’re the strong type. That’s exactly right.

Roger Dooley: Jumping back to eBay for a second, Ray, maybe you can provide some insight. One thing that’s always mystified me about eBay as I’ve been occasionally a buyer and a seller—I’m certainly not a power buyer or seller—but is the fact that their auctions end at a fixed time and that gives buyers the opportunity to try and jump in at the last minute, perhaps even using software and snag the item at a bargain price where other bidders who would probably pay more don’t have a chance to respond. It seems like other auctions allow for that. The auction time is extended every time a bid comes in so that the seller can get the best price.

I mean, it never made sense to me because actually I’ve lost as a seller where I saw that several buyers tried at the last minute and one snagged it but I knew that there would be more bidding. I’ve been contacted by buyers saying, “I missed out. If they don’t come through, let me know.” But also as a buyer where somebody came in a second before and knocked me off. Is there some logical economic reason for this? Is there a benefit for a time limitation?

Ray Fisman: This is really where the field of auction design has gone. Each one has a set of properties that can then be analyzed, thinking about things from the perspective of the seller and the buyer. One that I had thought had largely been defunct it turns out they use this in procurement auctions in Brazil these days, it’s called the candle auction. Where the auction would end at a random point in time. The reason it’s called a candle auction is it used to end when the candle was extinguished at some random moment.

Going back to your eBay experiences, in theory, there exists an auction mechanism which is used on eBay which obviates this problem entirely which is that if you’ve ever used eBay, you know you can just register a maximum possible bid. So suppose you want to buy an iPad and you’re willing to pay up to $200. You can just go in and you don’t have to keep checking. I can just say, “I’m willing to go up to $200.”

So if the highest bid currently is $99, eBay will automatically register a bid of $100 for you. If someone comes in and bids $150, it will automatically up your bid to $151. So that should really do away with the problem you just described because you should, if it’s worth $200 to you, you should be willing to keep upping your bid until you get to $200 and no more.

The so-called sniping comes in because you might not be quite sure what this thing is worth. There’s actually information in what others bid which tells you how much you’re willing to bid. So if no one else is bidding, you’re not actually willing to pay that much. So the only value in coming in at the last second, and yes, there is software that allows you to do that, is if you’re learning about what something is worth as others put in their bids.

I would add though that this is largely irrelevant, not just to internet commerce in other areas, but largely irrelevant to eBay these days. Most of eBay’s business is just fixed price listings. So it still has a reputation as an auction site but the vast bulk of its revenue comes from fixed price listings.

This is kind of an intriguing little fact about online commerce is that we used to think, you go back to say 2000, there were stories in the Economist and elsewhere talking about how we’d all buy and sell everything in one massive internet bazaar with constantly fluctuating prices. Hasn’t really happened. The reason why people think, and there’s some work on this by researchers at eBay and Stanford, the reason why things have changed, why there used to be so many more auctions than there are today, is it used to be a form of entertainment. Like you used to enjoy going to eBay and checking and rechecking what prices were. Now, it’s just a big hassle.

You want an iPad? Just go to eBay. See what the price is. Buy it or don’t. So now it seems like for eBay sellers auctions versus fixed price listing are essentially a form of what we call price discrimination. I’m not sure how common a term that is among marketers, different prices for different types of customers. The types who are very price sensitive but have lots of times on their hands, do get somewhat lower prices by bidding on auction listings. But then as you say, they have to keep going back, returning to the listing to see what the price is at.

Whereas people who are time scarce and money richer, they just want to get the transaction over with and that again is the bulk of eBay’s business today. As you may know, Yahoo used to have an auction business, that folded. Amazon used to, that folded. Auctions just aren’t a big thing online anymore.

Roger Dooley: Plus, I think eBay was so dominant that it made smaller auction sites, or less popular sites, put a lot of pressure on them, but with the decline in the entire field that you describe, it certainly makes sense.

My current book project involves friction. I think maybe we can wrap up by talking about that for just a few seconds. The first economist I encountered talking about friction was Ronald Coase whom you talk about in your earlier book, The Org. He wrote about transaction costs, which some other folks later simplified to friction, or characterized that as friction.

Basically his theory was that big companies minimize these transaction costs that would be involved in say sourcing raw materials that go into their products and so on because they could integrate a lot of these things internally. It seems today the idea of a well-integrated firm, thinking back to Ford in its early days where they started with coal and cars came out the other end, or iron ore. What happened? Why were big organizations efficient when he was writing about the economy and not so much now?

Ray Fisman: You don’t think Microsoft is a big organization? You don’t think Apple is a big organization? So average firm size has in fact grown. There’s a dominant perception that we see much less in the way of integration, vertical or horizontal. I’m not sure that’s entirely true. It’s certainly true that Nike does not own the factories that produce its shoes. We certainly see that sort of supply relationship.

But the notion that the internet or any other technology is going to do away with the frictions that make it valuable to do stuff inside a company and will make us all freelancers essentially buying and selling contracts on Upwork or whatever your site of choice is, I say this as a very enthusiastic user of Upwork. I have wonderful freelance relationships there. In an earlier era, I wouldn’t be able to find a physics PhD in Eastern Europe who was willing to format documents for $35 an hour.

So I don’t mean to suggest that these technologies aren’t valuable. But to say that they’ve removed frictions from the market I would strongly disagree with. Maybe a good way of concluding is to say that if we ever could create a friction-free economy, the very next morning business people would wake up trying to figure out how to add more frictions back in. Because in the absence of frictions, there really are no profits. Those get competed away by the market. So maybe it’s nice to aspire to, but it’s not the world we live in nor is it the world we will live in the foreseeable future.

Roger Dooley: Just looking at the physical world, you need a little bit of friction. We waste billions of dollars of fuel overcoming friction in autos but if there was no friction involved in automobiles, you’d find it pretty hard to stop the car and stay on the road.

Let me remind our listeners, we’re speaking with Ray Fisman, professor in behavioral economics at Boston University and coauthor of the new book, The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them and They Shape Us. Ray, how can our listeners find you online?

Ray Fisman: Probably the easiest is @RFisman on Twitter, R-F-I-S-M-A-N. Either that or I’m eminently googleable for better or worse.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will put that link and any other resources we talked about during the course of the show on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/Podcast. We’ll have a transcript of the show there too that you can read or download. Ray, thanks so much for being on the show.

Ray Fisman: Thanks again for having me.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.