You’ve probably had bosses you adored, and bosses you really disliked. But you likely respected both types, albeit in varied ways. What makes these types of leaders, and your reaction to them, so different?

You’ve probably had bosses you adored, and bosses you really disliked. But you likely respected both types, albeit in varied ways. What makes these types of leaders, and your reaction to them, so different?

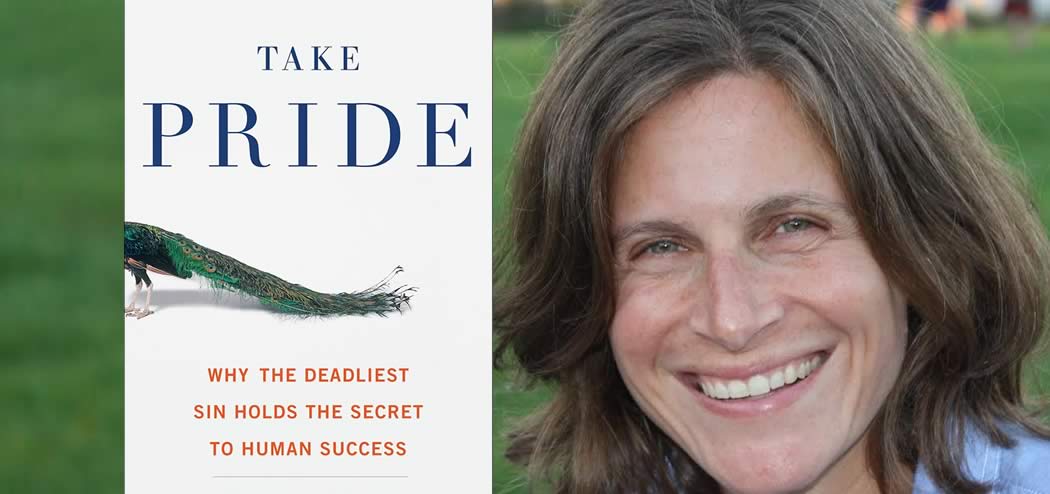

On this episode, Dr. Jessica Tracy of UBC’s Emotion & Self Lab, makes the case that pride, the first “deadly sin” we’ve all been warned about, is what distinguishes those two types of leaders. As detailed in her new book, Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success, Jessica and her colleagues have meticulously argued that pride can enhance your performance, for yourself and your team alike, if manifested in the right way.

Of course, Jessica’s research is much more nuanced than that. She talks about the two types of pride and what they usually look like in the workplace, and we discuss the different ways in which individuals gain influence over a group of other people.

Jessica also details the evolutionary basis of pride and our instinctive reactions to seeing proud individuals. We talk about leaders who have sought dominance versus prestige, including Steve Jobs and Lance Armstrong.

Jessica Tracy is a Professor of Psychology at the University of British Columbia and a Canadian Institute for Health Research New Investigator. Her groundbreaking research on the science of pride has been published in leading psychological journals and covered by hundreds of media outlets.

Jessica’s research combines emotion and science in a fresh and fascinating way, so be sure to tune in!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How confidence and self-esteem relate to the two different types of pride.

- Why it’s important to distinguish between self-esteem and narcissism.

- The divergent tactics people use to gain leadership in a group.

- How dominance can be used to lead a group, and the negative social effects it can breed.

- How pride can be seen as inspiring in some contexts, yet arrogant in others.

Key Resources for Jessica Tracy:

- Connect with Tracy: UBC Emotion & Self Lab | Twitter

- Amazon: Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success

- Kindle: Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success

- Audible: Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success

- Ep #114: Ego, Marketing, and More with Ryan Holiday on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Ep #126: Robert Cialdini’s New Insight: PRE-Suasion on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Steve Jobs

- Lance Armstrong

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. This is the point where I usually talk about our guest, what she’s accomplished, and so on, but I’m going to let someone else set the stage this week.

Just a couple of episodes ago, we had the legendary master of influence and persuasion, Robert Cialdini, on the show. He’s not with us again this week live unfortunately, but I’m going to quote his comments about our guest’s new book which is Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success.

Here’s what Dr. Cialdini had to say: “Jessica Tracy has flipped the script on pride showing that it’s not just a deadly sin to be avoided but actually a vitalizing virtue to be nurtured. She does it so convincingly and engagingly that she ought to be proud.” I’ve got to love the way he worked that “proud” into the last line. Welcome to the show, Jessica.

Jessica Tracy: Thank you so much. Thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley: Great. This is really nice timing on your release which almost coincides with Cialdini’s Pre-suasion book. I looked on Amazon and Take Pride and Pre-suasion both show up on each other’s “also purchase” lists. That’s good.

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, that is good.

Roger Dooley: I didn’t do my usual background intro, Jessica, so why don’t you explain who you are and what you do?

Jessica Tracy: Sure. I’m a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia which is in Vancouver, Canada. I run a lab there. We call it the Emotion and Self Lab. I’m the director of it. We do lots of research on emotions. In particular, emotions that relate to our sense of self, which really means emotions like pride, shame, and guilt.

Roger Dooley: I see you’ve got your sequel of books already potentially lined up there, “Why guilt is really good for you.” That sounds like fascinating work.

Let’s talk about pride. Obviously, that’s what we’re here for today. I love the premise of your book because it seems so counterintuitive. We all know that pride goes before fall. Pride is first on the list of the seven deadly sins. In fact, not too many episodes ago I had my friend and fellow Austinite, Ryan Holiday, on the show. His relatively new book is Ego Is the Enemy, so what’s so good about pride?

Jessica Tracy: You know, it’s interesting. You’re absolutely right that there is this dark, bad side of pride. In the book, I talk a lot about that. Really what we found in lots of research is that there are two different kinds of pride. We need to distinguish between them because, yes, hubristic pride, as we call it, which is the narcissistic, kind of arrogant kind of pride, that does relate to a whole bunch of psychological dysfunctions and social problems.

While that does exist, there’s also this other kind of pride, which we call authentic pride. That’s really a sense of confidence and self-worth. It’s focused on achievement and accomplishment. It’s what we feel when we’ve worked hard and we accomplish something. That’s a really positive thing because the feeling is really good. It’s very reinforcing as we would say. It’s something that we all want to feel because it basically is a message within our brains telling us, “Hey, you’re doing a great thing that’s putting you on track towards being a good social group member.”

The things that we feel proud of are things that our group likes about us, that our society want us to kind of do, whether that’s succeeding or helping others or being a good parent or partner. Those are the things that make us feel authentic pride. Because we want to get those feelings, we end up doing lots of hard work and often sacrificing things that are easier and more just fun and pleasurable in order to put in the hard work to get those successes that are going to give us those authentic pride feelings.

Roger Dooley: Really, in its good form, it’s a motivator for us. It makes us feel good and as a result we engage in activities that hopefully are productive and positive. Might be doing research or writing a book, or something, helping other people. Really what you’re saying up to that point it’s a good thing.

I love the name of the chapter “The Virtuous Sin.” In fact, I think that could’ve been a good name for the book as a whole. That’s pretty catchy too.

Jessica Tracy: That’s funny, we thought about that.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’m not surprised. Do you mean something different by that or is that just a catchy name?

Jessica Tracy: No, I think what I mean by that is sort of exactly this idea that there are two different things. That pride is both a virtue and a sin. It’s been called both throughout history. More often it’s been called a sin. I think that that’s been the predominant view historically from religious scholars and philosophers, but there have been hints at the virtue side of it.

Aristotle talked about it being a virtue to sort of have greatness and recognize that rather than deny it. You know, that if you have accomplished something it’s not a good thing to just pretend that didn’t happen. It’s better to be authentic about it. That really is what authentic pride is, acknowledging that you’ve worked hard for something and it makes you feel good.

The key is focusing on the next thing that you need to do to feel authentic pride and not starting to linger in it and focus on just how great you are. That’s what gets to hubristic pride.

Roger Dooley: A few years back, there was a sort of a big self-esteem movement where you would never criticize a child—always praise the child, like give yourself positive messages and affirming messages, and so on. Seems a little bit passé now, but how do pride and self-esteem differ, if they do?

Jessica Tracy: Pride is absolutely related to self-esteem. The argument that I make in the book and that we found in our research is that authentic pride is all about genuine self-esteem. It’s basically the self-esteem that we have that makes us just like ourselves and feel good about ourselves. It’s based on accomplishments. It’s based on hard work, but it tends to be realistic. The items that people use to assess it are things like “On the whole, I’m happy with who I am. I feel good about myself.”

It’s important that we make a distinction between self-esteem and narcissism, which isn’t just sort of “I’m happy with myself and I like myself,” but much more along the lines of “I’m better than everyone else. I’m the best one around.” Some of the items that we use to measure narcissism are things like, “If I ruled the world, it would be a better place. I’m really an extraordinary person.”

That’s a really important distinction because authentic pride we think is much more about self-esteem, that genuine sense of “I feel good about who I am.” Hubristic pride is much more about narcissism. In terms of distinguishing pride from these broader personality traits, one way to think about it is that pride is an emotion. It’s a momentary experience. We can experience it regularly, repeatedly over time. But it’s still just a momentary experience that when we experience we typically show a particular non-verbal expression. It drives us to engage in various behaviors.

Self-esteem and narcissism are both broader dispositional traits. They’re tendencies that characterize a person and their behaviors repeatedly over time and across situations.

Roger Dooley: Let’s talk a little bit about pride in a business environment. Most of our listeners are involved in business of some kind, whether they’re entrepreneurs or part of a bigger group. Many might be in marketing or sales, or situations where they have to influence other people.

One of the things that I found kind of interesting, you talk about prestige and dominance in particular you did some studies that involved eye tracking. A lot of our listeners are familiar with eye tracking from its use in marketing studies where you have people look at TV ads or even paper ads and determine exactly what they’re looking at when they’re experiencing emotion or doing something or whatever. But you were looking at people who were in group situations and watching who they were watching. Explain a little about those experiments and what you found.

Jessica Tracy: Sure, yeah. Basically what we wanted to do is we were really curious about how people get status. How people get influence over a group. We wanted to create a situation where a hierarchy, group differences and social status, would naturally emerge. We brought undergraduates into our lab, about four to six of them at a time. We had them work together to complete a task. It was sort of a task that is used in a lot of psychology experiments. It requires people to talk about ideas and think broadly and be creative.

Then what we did was we had them when they were done with the task rate how influential they believed everyone else in the group was, who had the most power over the group. Then we had outside observers. We had people watch videos that we made of these group interactions and we had them make the same rating. We had outside judges tell us also who they thought was most influential. That’s important because the people in the group might have biases about who they liked or who they didn’t like that could really influence their judgments. Whereas these outside observers would have that.

Then the other thing we had was we later on, because we had these videos, we had a new group of undergrads watch the videos while wearing an eye tracker device, as you pointed out. We just were curious on which people they would spend the most time looking at. Prior research suggests that it’s our human nature really almost to look toward the person who is the most powerful. That’s kind of where our eyes naturally gaze. There’s good adaptive reasons why we do that and why that makes sense.

We thought, here’s another way of figuring out who is the most powerful in the group is by seeing who these eye track participants spend the most time looking at.

Roger Dooley: That’s even true—just to digress—in primate communities, isn’t it? Primates tend to look at dominant individuals and actually even will find that a rewarding experience to be able to watch the high-status individuals.

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, I think that’s right. It’s definitely the case in children, and adults and humans. I think it certainly makes sense that would be the case in primates as well, at least some non-human primates, I should say.

Roger Dooley: Not human. Yes.

Jessica Tracy: The goal behind this research, what we were really curious about, was whether there were the two different strategies that people have talked about a lot in the literature that people use to get status. One is called prestige. It’s essentially getting status by being competent and smart and skilled and nice. These are the people that get high status because they work really hard. They do great things for the group. Everyone else in the group wants to give them high status because they like them. These are typically nice people who want others to learn from them and because they’re contributing something of value to the group. That’s obviously useful.

There’s also this idea out there from a totally different kind of side of the literature that’s argued that status is much more based on what’s called dominance. This is basically how almost every other animal does it. The idea here is that people get status not being nice, but by being tough and strong, threatening others and making it clear that “Hey, if you don’t give me what I want you’re going to be sorry.” They do that, often in non-human primates, it’s because they’re bigger and stronger and so others are afraid of them for that reason.

In humans, you don’t have to be bigger or stronger. You could have more money. You could wield your control over that resource in a threatening and intimidating way and manipulate others into giving you the power that you want.

You can think about it in the workplace. It’s the boss who says, “If you don’t do what I’m telling you, you’ll be fired.” That’s a direct threat and he’s commanding power by scaring others into following him. The way that he gets power, the reason others follow him, is not because they think he’s right, or they like him, or they want to follow him, but because they feel they have no choice.

We were curious, do both these strategies work? Does only one work? Here we’re going to have a group of undergrads, there’s no real threat. No one actually has power over anyone else outside of this little room where they’re solving this task. There’s really no reason that dominance should work. In that situation, will it just be prestige? What’s going to happen?

What we found was that in fact, using all those different indicators of social influence, so based on how everyone in the group rated everyone else, based on how the outside observers rated them all, and based on the eye tracking who people look at the most, both dominance and prestige worked.

In other words, the people in the group who all their peers said, “Yeah, I really respect him. He’s really smart. He knows a lot.” Those people got the most influence by all of our measures in influence. But so did the people in the group who everyone else said, “He’s really dominant. I’m kind of afraid of him. I don’t like him.” Here on the one hand they’re saying they don’t like him and they’re afraid of him, but they’re still saying, “Yeah, he was really powerful. He had influence.” And it turns out other people look at him.

Roger Dooley: How is that exhibited, Jessica? In other words, I get the prestige piece where somebody could come into this group of apparently random people and be helpful and have good ideas and so on. In this case, you didn’t have say somebody who was clearly a boss. So they couldn’t fire the other members and are not very likely to physically intimidate them. Where the dominant people just more forceful and outspoken? How did they show that dominance?

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, I think that’s exactly it. We coded the behaviors that we saw afterwards. We had people watch these videos and write down exactly what behaviors the various individuals were engaging in. You’re absolutely right. The people who were judged to be dominant, they moved their hands a lot, they used really expansive forceful kind of behaviors. They talked a lot. They tended to put down others, they were sort of insulting to other people in the group. They weren’t particularly friendly about it. They took control. They were just very controlling about the whole thing.

All of these things led them to be disliked. Again, people in the groups did not like having this one person come and take over. Yet at the same time they said, “Yeah, you know what, he led the group. He had influence. He helped determine what our decision was.”

We actually had an objective measure of influence in the form of persuasion. The task that they were doing, we had everyone complete the task first by themselves before they got to the group and then again with the group.

We looked at convergence between each person’s individual responses to the task and the group’s responses. Our thinking was, the people who will be most influential, they’re going to get others to go along with what they think the answer is, which means what they wrote when they did the task by themselves. To the extent that there’s more convergence between those two responses, that’s an indicator that you were really influential.

That’s exactly what we found from both the dominant and prestigious people. In both cases, we saw a good deal of convergence between what they had thought was the answer alone and what the group did. People in these groups, they were absolutely giving the dominance power even though here’s someone being threatening and intimidating and dislikeable.

Roger Dooley: I think in a real world setting, if you were an individual going into a meeting and if you weren’t the high-status individual or one of the high-status individuals in the room, you were a lower lever person. Your probably best strategy to be influential then would be to be very helpful, exhibit your knowledge, and so on, because what your research shows is that can be as powerful as dominance in some situations.

Although perhaps there could be conflict to, where a dominant individual is going in a different direction. Nevertheless, that would seem to be a better strategy than trying to exhibit dominant behaviors if you were not a high ranking individual. Or is that wrong?

Jessica Tracy: I think it’s a better strategy regardless of your rank. Whether you’re high rank or low rank, my guess is that doesn’t matter a whole lot in terms of how this stuff plays out. Either way, what our research suggests is that dominance is going to work to get you power, but it’s also going to have some real social costs.

We don’t like these people who engage in these behaviors and we never come to like them over time. We just dislike them more and more. There’s real social cost to that. You’re not going to have friends in the company. You’re not going to have people looking after you or who have your back.

What that means is you might get power in one specific domain because you’re being aggressive and intimidating and other people feel like they can’t really fight with you. But as soon as other people have a chance to take you down or even form a coalition against you, they will, because they really have no motivation not to.

Whereas prestigious people are well liked because in addition to being competent and smart and actually having good ideas, they’re nice to everyone else and they’re helpful, so others want to like them. Dominants are never well liked. That’s a really important distinction I think. If you have the choice, I would absolutely advise to go for prestige because then you can get power as well as friends and alliances.

Roger Dooley: Right, and it’s a longer lasting form of influence.

Jessica Tracy: Exactly. Prestigious people, even if you don’t have any more good ideas to contribute at some point, you’re not going to get kicked out of the group. You might not be as powerful as you once were, but the group will find a place for you because you’ve made yourself well liked and even loved by the group.

Roger Dooley: Where some of the groups monopolized by one or the other? Or did you find that an individual might have both types of people in the room where there would be somebody who is very influential because of their perceived knowledge and there’d also be somebody who is quite dominant because of their attitude or body language?

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, both. We didn’t see a real difference in that. The way we measured these things, I should say, is in a continuous scale. So every single person in the group is to some extent dominant and to some extent prestige. It’s not that there’s just one person who’s really, really, dominant. Although that might be the case. In general, everyone gets a score on both.

The other thing that’s important is that you can be both highly dominant and highly prestigious. There absolutely are leaders who’ve kind of gone this route. I always like to think about Steve Jobs as a really good example.

Roger Dooley: That was the name that was in my mind too.

Jessica Tracy: Oh, really?

Roger Dooley: We have to find some new examples I think.

Jessica Tracy: Yeah. He’s just someone who, clearly he accomplished a tremendous amount and he had some amazing ideas that absolutely revolutionized so much of our current technology. He was respected for that.

At the same time, once he started to get power, the way that he wielded it was incredibly dominant. He was really never very nice to his subordinates or even his co-workers. He was bullying. There’s so many quotes and anecdotes of him just being downright cruel to the people who were working for him and pushing them incredibly hard to do what he said.

He’s a great example of a dominant, but at the same time I don’t think he would have gotten where he was in the first place if he hadn’t been a little bit prestigious at least at some point.

Roger Dooley: Right. I think that he might be a rare example too of somebody who is both dominant and right. I think one danger of dominant leaders is that their solution prevails even though it may not really be the best solution that could be arrived at in a more cooperative or democratic fashion.

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s very true. It’s interesting you say that because we have another study that, it’s not yet published, but we have these results and I talk about it in the book. We had groups work together, again, to do a few tasks and we assigned one leader to each group. We just measured whether that leader happened to be someone who kind of was pretty high in dominance and used that strategy or was pretty high in prestige and used that strategy.

Then we looked at how the groups did on these tasks. That is, what their performance was like. We were really shocked because what we found was that the groups that were led by dominance did better on almost every task we gave them.

Roger Dooley: I wouldn’t have expected that.

Jessica Tracy: No, of course we expected the prestige-led groups to do better because those are people who are enjoying themselves and they should get into it and they respect their leader. We did find all that. Those people had a better time, they liked their leader better. They felt more pride in what they were doing.

The people who worked for a dominant didn’t like their leader, didn’t particularly like doing the task, didn’t really feel connected to their group. But if you look purely at performance outcome—we gave them three problem solving analytic tasks and one creativity task. On all three problem solving analytic tasks, the groups led by dominance did better. On the one creativity task, the groups led by a prestigious person did better.

Roger Dooley: Interesting. You sure you want to publish that result? It could lead to some really bad management behavior.

Jessica Tracy: Right. Well, my hope would be that we could learn from it and say, how can we foster performance while also saying we want prestigious leaders because that leads to much higher job satisfaction?

We found on every indicator whether people are enjoying the job, prestige wins. Given that we know we want that, we’re never going to get it with dominance. My suggestion would be, let’s figure out how we can boost performance with prestige. What is it that the dominant leader is doing to boost performance that the prestige leader isn’t?

My guess is a lot of it comes down to things like consensus seeking. It might be unique to the study that we did, because these are all undergrads working together. We tell them this person is the leader, but he didn’t do anything to get to be leader, right? He just was assigned.

So as a prestigious person, he might feel very uncomfortable kind of taking charge and saying “Okay, you guys, everyone has talked enough. Let’s reach this decision.” In the end, that’s sort of what you have to do to come to a decision when you’re organizing a group of people who have a lot of different ideas and thoughts. In contrast, the person whose personality tendency orients them towards dominance might have been much more comfortable doing that. It might just come down to that difference.

Roger Dooley: Jessica, you have some photos in the book of body language that demonstrates pride, things like a closed, crossed arms position, or hands on hip power pose, something like Amy Cuddy’s Wonder Woman. Is there a time and a place when people should use those or should not use those types? And are there any other ones you found to be important as far as pride goes?

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, that’s a really big issue. It’s a tricky question I would say.

Roger Dooley: We try to be tricky here, Jessica.

Jessica Tracy: That’s good. We’ve done research on the pride expression for about a decade. This is really how I first got into pride, is studying the expression. We found that it’s universal. That people all over the world recognize this display as pride.

I went to Africa and found that tribal villagers in Burkina Faso know it’s pride. We’ve shown that athletes all over the world spontaneously display it after winning say a gold medal in the Olympics. That includes blind athletes, even congenitally blind athletes. People who’ve never seen anyone else display this expression respond to success by showing it. We know it’s this innate part of human nature.

We know that it’s functional. We’ve done studies where we show that when people see a pride expression in others they have this automatic response where they can’t help but come to see the person as deserving high status. That’s the case even if we tell them contextually, “No, no, this person doesn’t deserve high status.”

In one study, for example, we showed them a homeless person showing pride. They know a homeless person is low status. That’s sort of the lowest status segment of our society. Yet when this person showed pride, observers still have this automatic response that they can’t really override that this guy deserves high status. It’s a very powerful signal. I think that makes sense because it’s an evolved signal. It comes from our non-human ancestors.

We see evidence of similar displays to pride in some of our primate cousins. We sort of can’t help the way that we perceive these displays. Now that said, I think you’re absolutely right that there are costs to displaying pride. We’ve shown that as well. People who show pride that is considered to be too much or inappropriate to the situation, or unwarranted, they are disliked. They might still get power. It’s a neat thing.

We’ve shown that people have this automatic response and can’t help but see them as high status. But you can see someone as high status at the same time as you’re thinking to yourself, “I really don’t like this guy. He’s way too arrogant. I don’t want to hire him.”

It’s a complicated issue because people want to get status. If you’re applying for a job, you certainly want to convey a sense of confidence. We’ve shown that people applying for jobs who show pride are more likely to be hired. At the same time, you’ve got to be careful. If you show it in a way that’s considered to be too much, you’re going to be disliked.

We have one study where we look at the displays of pride by people requesting charitable aid through a micro lending charity that has a website where people can go on and donate or lend money to these people. Here, people are requesting aid to support a business that they’re starting. You would think, well this is a situation where you want to show pride. You want to convey that you’re someone who can successfully do this business.

In fact, what we found was that the more pride people display in those profiles where they’re requesting help, the less financial aid they actually get. They get less money as a result of their pride displays. We think that’s because it comes off as arrogant. Here’s a context where you’re asking for help. You don’t want to show pride. It’s not the right situation to do that.

Roger Dooley: Very interesting. I supposed too that different elements of body language, even though they may all be associated with pride, will be perceived differently. The closed, crossed arms, for instance, to me that might symbolize pride, but it also is a classic closed mind, “I don’t want to hear what you have to say” position, which would be generally in most situations not a major plus. Where a more open, large stance might also be related to pride but it would perhaps be a little bit more welcoming to the person you’re interacting with or with a group.

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, I like that. That’s a really interesting hypothesis. That particular distinction has not been specifically tested in terms of whether one is more disliked than the other. Both get power. Both are linked to power and pride, but that’s really interesting.

Roger Dooley: I guess Lance Armstrong is an example of the whole spectrum of pride, right?

Jessica Tracy: Yeah, absolutely. I use him as an example that way in the book. The idea being that he worked incredibly hard as a kid, as a teenager. He just spent all of his free time biking. That’s painful, right? Anyone who’s done lots of long distance riding knows it’s not something that you just—pure pleasure. As much as going for a bike ride sounds fun, the hours and the time and the speed he was doing it, it really comes down to pain.

The only way that he could possibly have motivated himself to do that is by a desire for pride. A desire to feel good about himself and knowing what he could possibly accomplish and the kind of person he could be if he put in all that hard work. It did. It paid off. He obviously became known to be the fastest cyclist in the world and he won all kinds of honors and became probably the most famous cyclist in the world.

Then, apparently, he let it go to his head. This is really common. Once we do all these things to achieve pride and then once we feel that pride, it feels really good and it’s very tempting to just sort of experience the feeling and try to relish it, exaggerate it. Try to figure out ways to just keep that feeling going rather than thinking, “Okay, I got that feeling because I worked hard. What’s the next thing I can do to make myself a better person to go for it again?”

That’s a much harder thing to do instead of just saying, “Hey, if I let other people know about the success, that’s going to feel really good. How can I get more praise for this because that’s going to feel really good?” That’s where hubristic prides come in and I think we see that switch with Lance. The reason we know it is because of course he began engaging in behaviors that really made it so that he could no longer prove himself to be the fastest cyclist. He was doping, which means that even if he wins races, we can’t know if he’s winning because he’s truly the best out there or because he’s cheating.

I think it’s just fascinating that someone who could start out wanting to prove—not only to others but to himself—that he was the best, would engage in a behavior that actually prevents him from doing that. He can no longer prove to himself at least that he is the best. It shows that’s a very different motivation. That’s what hubristic pride does to people.

Roger Dooley: Seems like these days in politics there’s a lot of that, hubristic pride on exhibit. Although I think it almost goes with the territory, because you mentioned that when you have the feeling that if you were running things, the world would be better. I think most politicians really believe that. They think they can make things better if only they can have the necessary power. In one sense, that’s not necessarily a bad thing if they have good ideas and they can affect positive change. That’s great. It’s a fine line I guess.

Jessica Tracy: I absolutely agree. I think to run for president you have to have some degree of narcissism. There has to be some part of you that just thinks, “I really might be the best at this.” Which is sort of an amazing thing to say in a way.

Roger Dooley: It’s sort of imposter syndrome on steroids because those of us who do public speaking or write a book or something, there’s always that sort of little element of “Wow, should I really be doing this? Seems like there are people who are a lot smarter than I am out there.” To have that feeling of confidence that you can be the best president possible, that’s really a step beyond.

Jessica Tracy: Absolutely. Studies have shown that presidents in general do score higher in measures of narcissism than the average public. There are still major individual differences within just presidents. Which I think is kind of what you’re getting at, that some presidents are more narcissistic than others.

I think some at least follow rules of, “I know that it doesn’t look good. People don’t like it when someone comes off as being too arrogant, so I’m going to try really hard to suppress that. I’m going to avoid talking about myself constantly. I’m going to avoid talking only about my accomplishments without mentioning all the other people who are involved. I’m going to avoid bragging.”

That’s the important thing right? That even though we know, okay, you are president, you ran for president, at some level you think you’re pretty great. If you can avoid displaying that through every behavior that you do, just basically avoiding bragging and being overly grandiose, you can still be well liked. And many presidents are very well liked despite the fact that we know on some level they think they’re great.

Roger Dooley: One final question, Jessica. How as individuals do we make good use of pride but avoid falling into that trap of just going too far where we start engaging in behaviors that are more negative because our pride has turned to narcissism or has just gone too far?

Jessica Tracy: It’s a great question. My thinking about it is that the thing that gets us pride is the hard work. I say hard work, that’s one form of pride. Another might be putting a lot of work into caring for others. I don’t just mean hard work at whatever your job is or whatever task you’re doing. It could be in a relationship, being a good relationship partner or a good parent. That’s what gets us the pride.

I think the key is, think about the kind of person you want to be. Think about who you are and what’s important to you and then what you need to do to get there. The work that it takes to get there, that’s the best way to get pride. It’s that feeling of, “I’m accomplishing something that’s meaningful and that feels really good to me.” You feel good about it even while you’re doing it, even before the accomplishment comes.

I think the tricky part is once the accomplishment comes and you do feel those pride feelings as a result of it, that’s where it’s sort of a decision of saying, okay, rather than gloating, rather than really celebrating this far more than is necessary, rather than just focusing all my efforts on how I can feel good about myself for this, I’m going to think about the next thing I can do to keep being that kind of person that I want to be.

It is complicated. I certainly don’t want to say to people, don’t ever feel pride, because that’s not what I think. The message of the book is take pride. That authentic pride is something we evolved to experience and it’s functional and adaptive and we shouldn’t pretend that it’s not part of who we are or that it’s bad for us. I don’t think that’s the case.

It’s just a matter of allowing ourselves to feel the kind of pride that does push us to work hard. Then trying to tamp down and maybe avoid or suppress the kind of pride that’s more about feeling superior, feeling grandiose, starting to think that we’re better than everyone else.

Roger Dooley: Let me remind our listeners that we are speaking with psychologist Jessica Tracy author of Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success. Jessica, how can our listeners find you and your content online?

Jessica Tracy: My lab at UBC has a website which is ubc-emotionlab.ca. That’s probably the best way to learn about our research and there’s links to the book there which of course is Take Pride: Why the Deadliest Sin Holds the Secret to Human Success. You can buy the book through there or learn more about it or the kind of work we do.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link to that place, to your book, Jessica, and any other resources we talked about in our conversation on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have downloadable text version of our conversation there too.

I guess the listeners who have gotten this far might wonder why they’d want the text, but I know when I listen to podcasts sometimes I remember something that was said halfway through that I want to refer back to. Trust me, it’s a lot easier to the skim through the text version than to try and find it in the audio playback. Jessica, thanks for being on the show and good luck with the book.

Jessica Tracy: Thanks so much. Thanks for having me.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.