Fears about artificial intelligence are about as old as the concept of AI itself. But for many proponents of this technology and others, a symbiotic relationship that benefits all of us is the more likely outcome.

Fears about artificial intelligence are about as old as the concept of AI itself. But for many proponents of this technology and others, a symbiotic relationship that benefits all of us is the more likely outcome.

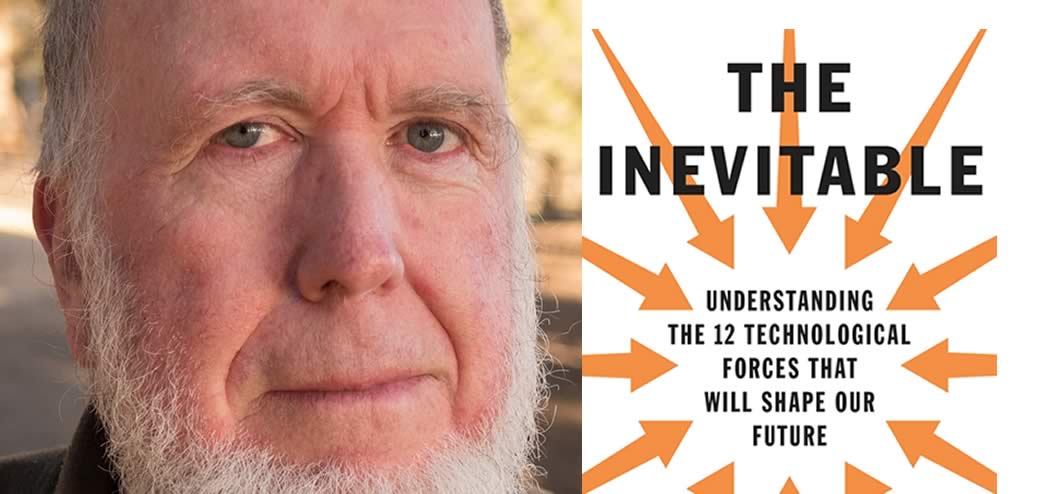

Our guest today is Kevin Kelly, a co-founder of Wired and the author of the new book The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future. Kevin falls firmly into the optimistic camp as he details in his exploration of the tech forces that will improve life around the world in the coming decades.

Kevin and I start by talking about the early days of Wired and how he has since transitioned to other types of writing. We then discuss “creeping betterment” — the concept that technology enables us to improve the world little by little each year, the benefits of which are compounded over time.

Kevin also talks about how humans and AI will have complementary types of intelligence in the future, working together to solve problems that couldn’t be surmounted with human ingenuity alone.

Kevin Kelly co-founded Wired in 1993 and served as its Executive Editor for its first seven years. He is also founding editor and co-publisher of the popular Cool Tools website, which has been reviewing tools daily since 2003.

Kevin also co-founded the ongoing Hackers’ Conference, and was involved with the launch of the WELL, a pioneering online service started in 1985. His books include the best-selling New Rules for the New Economy, The Silver Cord, an oversize catalog of the best of Cool Tools, and his summary theory of technology in What Technology Wants (2010). He has also written a graphic novel about robots and angels, titled Out of Control.

Kevin has worked in the technology and future-casting field for many years, and is an engaging and optimistic thinker. Be sure to tune in!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why Kevin thinks technology is leading us to a “protopia” rather than utopia or dystopia.

- How the seemingly tiny improvements we make to the world each year multiply over time.

- Why there is no such thing as general purpose knowledge, and how this is good for our relationships with AI.

- How society is shifting from owning things to simply accessing them.

- Kevin’s thoughts on home automation, now and in the near future.

Key Resources for Kevin Kelly:

- Connect with Kevin: KevinKelly.org | Twitter | Cool Tools

- Amazon: The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

- Kindle: The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future

- WIRED

- Deep Blue versus Garry Kasparov on Wikipedia

- Ray Kurzweil

- Nest smoke + CO alarm

- Amazon Alexa

- If This Then That

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week has multiple claims to fame. For one, he co-founded Wired in nineteen ninety-three and is still on the masthead as Senior Maverick. Even before that, he helped launch The Well, a pioneering online community. He’s a best-selling author, having written New Rules for the New Economy, among other books and his newest book, published just a few months ago is, The Inevitable: Understanding the Twelve Technological Forces that will Shape our Future. Perhaps the coolest thing though, is that his personal domain is a mere two letters long, kk.org. Welcome to the show, Kevin Kelly.

Kevin Kelly: Hey, it’s my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley: Great. Kevin, is there a story behind that domain? Did you snag that in the very early days of domain registration or manage to grab it later?

Kevin Kelly: No, it wasn’t early enough because, if I was really smart, I would have been kk.com. It was still in the mid-nineties, so I paid for it. It was a doctor in Hong Kong who wasn’t using it and I bought it from him. I remember and I was working at a time when anybody could have claimed any domain name they wanted for free. There wasn’t etiquette at the time, which it was considered ill form, kind of impolite, to actually buy, not buy, but to claim a URL that you weren’t using. The thing was, you could get whatever you wanted, but you actually had to then put it up and put it on a server and get it going. You couldn’t just hold them. I had friends who weren’t playing by the rules and as that started to break up, they started to register all kinds of names that they could think of. I wasn’t that smart. I kept thinking, there’s no way these things are going to become valuable. We’re going to have to have multiple … Domains will be dot everything and, of course, I was wrong.

Roger Dooley: Well, yeah. If you talk to folks that go back to the early days of domain registration, the one regret everybody has is that they failed to register cars.com or many of the other domains that now are worth millions each. Be that as it may, kk.org still is pretty nice.

Kevin, I’m sure many of our listeners are Wired readers. Wired is closing in on twenty-five years now, how does a publication like that stay relevant, particularly, in an area that’s changing so quickly and so often?

Kevin Kelly: It’s a really good question. Full disclosure, I do not edit Wired Magazine these days. I don’t work for them. I continue to have a title, which means I do one big piece a year for them at freelance rates, so to speak. I have to say that I don’t think I really would want to edit Wired these days because it’s really, really hard to be relevant. When we were doing Wired before it was sold out from under us, we were running a pirate ship and now, after twenty-five years, Wired is more like a flagship. That’s a very different sensibility and I’m much more likely to want to keep over turning the tables and reading the assumptions and tweaking the conventional wisdom. Whereas, I think Wired today, is a little bit more like, “We’re the authorities. We give the [inaudible]. This is what’s important.” That’s what I see as this role in this kind of seething news and a lot of stuff from the digital world, which is percolating, almost unstoppably, through our lives. I think Wired is much more in a kind of, sorting things out and trying to say, “Here’s this really important. Look at this.” I think it’s role as, sort of, a herald from a distant subculture, a distant future, is gone and everybody is trying to report on the future now. It’s a much more competitive landscape.

Roger Dooley: Really, since its start, technology has become part of everyday life for everybody, where back in the earliest days, a lot of folks really didn’t have much of a brush with technology, at least, as far as having it in their pocket or all over their home.

Kevin Kelly: Yeah. Technology is a very squishy word. We tend to use it to mean, anything that was invented after we were born, when in fact, of course, it’s everything and most of the technology surrounding us is very old stuff. From concrete to wood lumber, even to things like sheet rock and plumbing and all that. That’s most of it, which we don’t see as technology anymore. It’s just completely invisible to us. Technology today, of course, will become invisible tomorrow. It was this digital stuff that was coming that we thought was really important. It was this domain of nerdy, pimply guys, teenagers in the basement and we kept saying, “This is bigger than that.” My own experience of being online since nineteen eighty-one or so, is that, no, this is real stuff, there’s real communities, there’s real things happening. It’s not about teenagers and CB radio, it’s big, it’s going to touch all aspects of our lives. That’s what we were trying to educate people saying, “What’s happening here is fundamental shift in the culture and it’s going to be mainstream.” That was something that we repeated many, many times and it was just really hard for people to believe.

Roger Dooley: Well, it was a good call twenty plus years ago, so I think, maybe, that gives some credibility to your prognostications in this book too, Kevin.

Before we leave Wired, I have one quick question, recognizing that you’re not necessarily running the show anymore, but do you think the graphic designers there go out of their way to make some stuff hard to read? Like, reverse white type on a silver background? Occasionally, I just find myself flummoxed, where I’ve got to hold the magazine at a good angle just to read the content.

Kevin Kelly: You are so right. It infuriates me. It’s not just the current regime. Even in the early days of Wired, I constantly was losing battles with the designers saying, “Hey, how about some radical legibility. How about that?” Something where it’s so easy to read. We would sweat over these articles for … Just killing ourselves and then, they’d be published and nobody could read them because of the design. It’s like, this is not in anybody’s favor. I have a long going gripe with the illegibility of some of the Wired articles, including currently today, where they bump up the column of text against an image. It’s like …

Roger Dooley: Yes, I’ve noticed that, where there’s no spacing at all.

Kevin Kelly: Why are you doing that? Why are you making it hard? I lose these battles all the time, what can I say.

Roger Dooley: I have a theory, Kevin. There’s research on cognitive fluency that shows, when something is hard to read, it may seem more difficult of profound, so perhaps that’s what they’re going for.

Kevin Kelly: Yeah, I don’t buy it. That’s one thing I would definitely change if I was back there, but I’m not, and so … By the way, you can always read it online, which is pretty legible, the version online. I don’t think the paper version of any magazines have more than five years in them, so this may come a moot point, although, they may figure out how to …

Roger Dooley: How to transfer that to digital or …

Kevin Kelly: Exactly, how to wreck reading online too.

Roger Dooley: Something to look forward to.

Kevin Kelly: Yes.

Roger Dooley: Let’s talk a little bit about your new book. Kevin, you say that technology isn’t leading us to utopia or dystopia, which are probably the two most common forecasts, but protopia. What the heck is that?

Kevin Kelly: Everybody knows that utopia is a, sort of, final state, the omega point of the world was at war, perfect harmony, total enlightenment, this sort of dream state, heavenly state. Dystopia, of course, is the opposite and it’s this place where everything is breaking down, the future is a world of dysfunction. That, actually, is almost the standard Hollywood and current science fiction view. I can not think of a single science fiction movie that describes a future that I want to live in.

Roger Dooley: Perfection is kind of boring, really, compared to humans pitted against killer robots and so on.

Kevin Kelly: Right. We have dystopias and we have some utopias, but nobody believes them and I don’t believe them either, I think they’re impossible. What we do have and where we are going, where we have been going is, progress. Actually, real progress so that every year, the world is a little, tiny bit better than last year. That tiny, whatever it is, it’s one percent, half percent, difference. When it’s compounded annually, as you know, this is one of the most powerful forces in the world, so we have civilization by compounding a tiny, tiny, delta of betterment every year. Sometimes, because it’s so tiny, half of a percent difference, it seems invisible to us, but it’s going on and that slow creep to betterment is what I call protopia. From progress, the sense of forward motion. It’s basically saying that there is progress, the progress is real. Almost every metric that matters to humans, life is getting better, but not by much, each year, but it’s slowly creeping better and better. That slow betterment is protopia. It’s possible.

It’s very possible that after two hundred years of steady progress, that next year it could stop, it could collapse. That’s possible, but unlikely. My optimism in the future is based in history. It’s based on the fact that, for two hundred years we’ve had protopia. We’ve had progress. We have made the world a little tiny bit better than the previous year and so, it’s probable that, that will continue, at least, the next twenty or thirty years. That’s where I get my optimism from.

Roger Dooley: That’s good. That is an optimistic outlook, I think. It’s probably a lot more plausible than utopia.

Kevin, we aren’t going to have time to cover all of your twelve forces, but the first one you talk about is, cognifying, which has to do with artificial intelligence and applying it, sometimes, to things that aren’t necessarily obvious candidates for an AI intervention. Talk a little bit about what you see happening in that field.

Kevin Kelly: I use the word cognifying, which is sort of an obscure English word to mean, although the way I’m using it is, to make things smarter. I want to get away … There’s a lot of baggage, a lot of cultural baggage with the idea of artificial intelligence because we, kind of, all have in our mind what we think that is and we often confuse it with lots of other things. We think of a very human like intelligence, but it’s artificial. What I want to emphasize is that, the AI’s that we actually will be making, these artificial smartness things, these [inaudible], are in the most part, not like humans at all. In fact, that’s why we’re making them. The reason why we want an AI to drive our cars is because they aren’t going to drive like us. They aren’t human like, they aren’t being distracted, they don’t have conscious ruminations, daydreaming and stuff, they’re just going to really focus on driving. So far, the evidence is that they are much, much better drivers. Even though there’s been one or two fatalities, they’re still, compared to the millions of miles they’ve driven, they’re nowhere near as murderous as human drivers. Humans, last year, killed … Human drivers killed one million people and we just somehow accept that, but we should outlaw human drivers. We’re just terrible drivers.

The reason why we want a lot of the artificial intelligences is because they think differently. Because, it’s a different kind of thinking and thinking differently, is actually the engine of innovation and wealth creation and much of what we desire in this new economy, is thinking different. We are going to, basically, invent hundreds of different kinds of minds, artificial minds. Many of them that we have invented, like a calculator, are already smarter than us in certain things like arithmetic or spacial navigation or recall. They’re already smarter than humans, but the point is that our own intelligence is not a single dimensions. It’s not like it’s just IQ, which gets louder from a mouse to a chimp to an idiot to a regular person to a genius. Our intelligence is very complicated, we have dozens of different types of thinking in our minds and some of those types of thinking can be exceed my machines. That mix of things cannot be made by silicon and we’re not even going to try. We’re going to make whole new types of thinking that haven’t existed before, just as, we made new types of flying inspired by biology and flapping wings, but we made artificial flying which doesn’t use flapping wings at all. It’s new. We are going to make up new types of thinking to accomplish or to solve problems that we cannot solve with human intelligence alone.

One thing I just want to emphasize is that, these things that we will be working with, don’t think like humans. They can exceed human capabilities in many dimensions, but not all of them. You can’t optimize everything that’s engineer … Dictum engineering truism, which is that you can’t optimize all things. We’ll make these, optimizing different things and we will work with them. We are not going to be against them, we will work with them.

After Gary Kasparov lost … He was the world chess champion, he lost to Deep Blue the world chess champion. He complained. He said, “This super computer, AI, IBM Deep Blue, it had access to a database of every single chess move or play that had ever been done. If I had access to that same database, I could have beat Deep Blue.” He decided to make a brand new chess league, where you could play with a database or you could play with an AI or you could play as alone, as a human, or you could play just as an AI. He called the teams of human plus AI, he called them Centaurs. Here’s the thing, in the past three or four years, the best chess player on this planet, is not an AI, it’s not a human, it’s a centaur. It’s a human plus AI. These are complimentary type of thinking and that’s what we’re going to be do- We’re going to be paid in the future by how well we work with AI’s. How much of a team we are. …And so we’re going to have more opportunities because of AI’s, more jobs, more tasks, than ever before.

Roger Dooley: I guess your vision differs a little from Ray Kurzweil, where his prediction is more focused on … I was saying that sometime in the first half of this century, that machines will be smarter than humans. It will reach that level and surpass it. Really what you’re saying is that it’s not the general intelligence concept, but performance in very specific domains, that will be the differentiating factor.

Kevin Kelly: Yeah. I will make the audacious claim that there’s no such thing as general purpose intelligence. Humans don’t have general purpose intelligence. We have a very, very specific kind of intelligence that was evolved over millions of years, for our survival. Just as you can’t say there’s a general purpose organism. There’s a general purpose animal. There’s no animal that’s general purpose. There are some that may be able to live in a wider range of biomes like humans, but we are in no way … The cost of that is that we are pretty defenseless. If it was not for technology, we wouldn’t survive. We would be a very small population. There is no such thing as general purpose intelligence. This is a complete [inaudible] because of our own ignorance. We haven’t undergone the Copernican Revolution yet. Which, as you know, we used to think that we were the center and all the planets revolved around us and then, we discovered, “Oh my gosh, not only are we not the center, but we’re like the edge of the galaxy. We’re just way in a corner.”

We have the same kind of thing coming up now with our intelligence, which is we think we have a universal, general purpose intelligence. All the intelligence will be satellite versions of us or there’s only one kind. No. There are a million different kinds of intelligences and our intelligence is way in the corner. It’s just one tiny collection of different types, different modes and it’s not general purpose in any way. This is going to be a big shock for a lot of us, of humans, as we start to invent a million new species of intelligences and all of them are very different. We’ll see, we’re not the center at all. We are way at the edge.

Roger Dooley: Let’s move on to one of your other topics, Kevin, about how people consume media. One thing I found kind of amusing was your discussion of, I guess, what you might call, just in time reading. Now that a lot of the reading that you do is digital and that content is stored in the Cloud anyway, versus some kind of local device, why buy a book before you’re going to read it? Amazon … Keep it until you’re absolutely ready to read it right now and then, you can pay for it. I’m wondering, as an author, should you really be promoting this strategy because, probably, ninety percent of business books go unread. That would be really bad.

Kevin Kelly: Yeah, no. It’s true that this is part of a larger shift from owning things to accessing things, which I do talk about in the book and it’s not just books, it’s music and movies. If you can have access to any movie, any time, anywhere in the world, then why would you want to own it then, have all the liabilities and the chores of owning things. Keeping it updated, backed up, secured, etc… Much better is just to have access to it, so you reach and you get it exactly at the moment you want it and then, you give it back or you let go of it and that’s the end of it. I’m sure that’s effecting sales of books and things because most people are probably behaving like I do, which was, hey, there’s … I buy the book, it sits in one file on Amazon and when I’m going to read it, it’s in another one. It’s just moving between files on Amazon, why buy it before hand? I think that’s true and it’s going to be true, not just with digital things, but I think increasingly, even of physical things.

Uber is a good example, it’s like, why would you buy a car if you could summon a car anytime you wanted, anywhere, instantly and ride it and just leave it off and not have to park it or anything else, all the other responsibility for it. That’s better than owning it. I think this is spreading way beyond books and it is a challenge for people making stuff because if people aren’t going to buy them, but you’re just going to subscribe to them and stuff, this changes the business models and economics of it. It’s going to shift things.

I did come up with a really ingenious way to try to encourage people to read my book. In a certain sense, as an author, I really don’t care if they buy the book. I really don’t. I want to people to read the book. I was thinking, how can I get people to read the book, whether they buy it or not? I came up with this idea of using a Kindle, where you could purchase the book for whatever it is, four dollars, and I will pay you, say ten dollars, if you actually finish reading it. An AI could tell whether you are actually reading the book or not, on say, the Kindle because every time your page is turning. The idea would be that, that difference … That most people would still be buying the book, but not finishing it, so that there would be more people not finishing it. That I would make enough money from those unfinished readings, to pay for the people who did finish it. None the less, there would be a total gain in, at least, the number of people attempting to read the whole book.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I think if you had a little progress bar too, as you read, showing how much money you were saving, that would be a real incentive.

Kevin Kelly: Right. Jay Walker at digital, the guy who did Priceline reverse auctions, he said this was a patentable idea, but a patent gives you a right to sue and didn’t really want to spend my life doing that. I said, I’ll just publish it and maybe someone will make it happen. I think the general lesson that, we’re moving away from the virtues of owning things to the virtues of having access to things, that is a really large scale, central event and movement that’s happening and will continue in the next thirty years.

Roger Dooley: Kevin, what’s your take on home automation or smart homes or whatever you want to call that area? All the way back in nineteen eighty-six, I started a magazine called Electronic House. It was focused on that market. To demonstrate how stupid I was then, not only, even a few years later, I wasn’t buying domains when I should have been, I was actually critical of some the industry pundits who thought it was going to take five years or more for that market to develop. I predicted they would go more quickly. Thirty years later, we’re getting there, but not there yet. In fact, I was just reading that there’s actually been a little bit of a downturn in interest after a surge a few years ago when Google invested in Nest and there was a big push. Now the bloom has gone off that rose a little bit, not that the market isn’t going to eventually develop, but it seems to be, adoption is slower than expected, so I guess that ‘s a recurring theme. What do you think about that area?

Kevin Kelly: Yeah. I’ve been a very, very slow adopter myself. I do have a thermostat and we put in the new Nest smoke detector, Co2 thing. For me, actually, the … Another little burst forward in this would be the Alexa, which I’ve been very, very impressed with the Amazon Alexa system where you can talk to Alexa and ask it, like a butler, to do certain things. In my conversation with other people who have it, one of the things that they’re using it for is to turn down shades, turn up lights, change the temperature of the … Make it hotter or make it warmer, using all these kinds of things. I don’t know if it’s going to bring in the Jetson dream yet, but there’s certainly, I think, this conversational interface that is emerging, this ambient presence that’s always there waiting to hear and where you can do things by just speaking, I think that will help, but I think the vision of the smart house … I think the benefits of the analog world, in this respect, are still very, very present and may be even a sanctuary for many people who spend their lives virtually. I’m not expecting a huge leap in, even the next twenty to thirty years. I’d be very surprised if there was huge, significant differences. I think this is going to be incremental and slow, even for the next twenty-five years.

Roger Dooley: I can see that, Kevin. I think Alexa, which I also have and I also really like, it’s kind of a Trojan Horse where it can introduce people to these concepts in a very simple way where they don’t have to invest in a whole house system and program it and so on. You just realize, “Gee, I’d really like to be able to turn that light off on the other side of the house. Oh, Hey. Alexa can do that.” That’s really simple and with it’s open nature of being able to link up with things with tools like If this, Then That, it really lets you do all kinds of unexpected things, but you don’t have to do it all at once. You don’t have to set it up, you can just do these things as you need them.

Kevin Kelly: Right. I would like to be able to say like, irrigation system. If it’s raining or even that sense of have it be aware of the weather and all this kind of … The complexity and the number of buttons and devices that you need really became a real significant hurdle because people, like myself, didn’t want to have another control unit. Having the single control unit, having the single interface, which is, I’m just going to say what I want. Okay, then suddenly, now I can say a lot more things that I want, but I just didn’t want to have another control unit and all this stuff, this complexity. It far exceeded the benefits that I was getting. I think having that kind of ambient interface will really encourage people to have other things that they want done and I think that will drive the slow movement towards the smart house.

Roger Dooley: Kevin, I didn’t get to half the things I was hoping we’d talk about. We could go on for hours. Let me remind our listeners that we are speaking with Kevin Kelley, co founder of Wired and author of the new book, The Inevitable: Understanding the Twelve Technological Forces that will Shape our Future.

Kevin, where can listeners find you and your content online?

Kevin Kelly: You already mention my domain name, kk.org. I’ve got most of the things there, besides my writing. I have been writing this really cool site called Cool Tools for thirteen, fourteen years. We review one cool tool per weekday. It’s user generated and tool in the broadest sense of the word. Stuff that ‘s useful to you. It could be a hand tool, could be a power tool, it could be a map, it could be an app, it could be a service. Its advantages is that it’s pretty wide and broad and we’ve been going for a long time. We have a great bunch of stuff, so that’s an ongoing thing at Cool Tools, which is on kk.org. I have another website where I review the best documentaries in English and have been doing that for many years, although, I have to say, I haven’t updated it recently. There’s a lot of great stuff there, particularly, if you have Netflix and Amazon Prime. I have other stuff too. A graphic novel in two volumes. That’s the place, kk.org and I am also kevin2kelly on Twitter. I don’t post much on Facebook, but Twitter is probably the best.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link to all of those resources and anything else we mentioned during the coarse of our conversation on the Show Notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a handy PDF copy of our conversation there too.

Kevin, it’s been a real pleasure having you on the show. Can’t wait to see how your predictions pan out. I really encourage our listeners too, to pick up the book because, we are all really dependent on the future for our own prosperity and I think Kevin has got some great insights in there.

Kevin Kelly: Great. Thank you for the great suggestion and I really appreciate your great questions as well. It was a delight to be here.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.