Today, I am excited to welcome my guest, Dr. Barry Schwartz. Barry is a best-selling author and researcher that most of our listeners and readers will know well. As the Dorwin Cartwright Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at Swarthmore College, he studies the link between economics and psychology.

Today, I am excited to welcome my guest, Dr. Barry Schwartz. Barry is a best-selling author and researcher that most of our listeners and readers will know well. As the Dorwin Cartwright Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at Swarthmore College, he studies the link between economics and psychology.

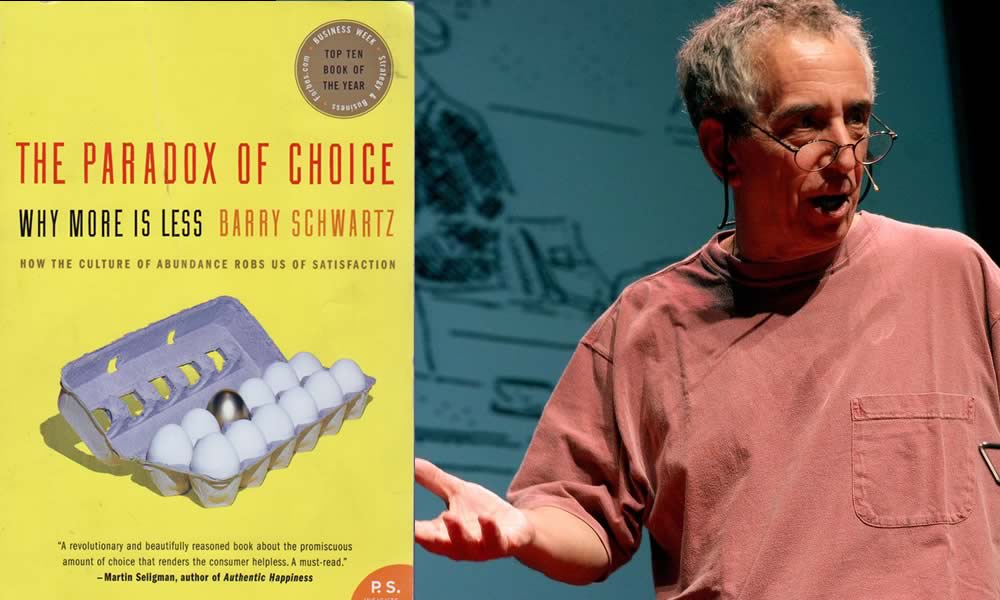

More than ten years ago, Barry wrote his huge best seller, The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More. Barry surprised many readers by arguing against the conventional wisdom that more choice is good. He showed the opposite could be true, and too much choice could even make people less happy. His TED Talk on the topic has been viewed more than 7 million times.

Barry joins us today to discuss what all business owners need to know about the choices they are offering their customers. He explains the research behind his book and addresses some recent research that attempted to disprove the negative effects of choice. Listen in to learn how you can find the right balance of options that will maximize your customer’s satisfaction and your sales.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast, and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why some employees fail to enroll in desirable 401K retirement plans.

- How too many choices can lead to buyer paralysis.

- How hard-to-read fonts can have an effect on cognitive fluency.

- Why it is vital to your business success to determine your offer “sweet spot.”

- How limiting the options available to new home buyers saved a home builder thousands.

Key Resources:

- Amazon: The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More by Dr Barry Schwartz

- Kindle: The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More by Dr Barry Schwartz

- TED Talk: The Paradox of Choice by Dr Barry Schwartz

- Connect with Barry: Barry Schwartz | Twitter | TED

- Psychology Today: Why Selective Colleges (and Outstanding Students) Should Be Less Selective by Barry Schwartz

- Neuromarketing: Mega-Branding: The Purple Oreo Problem by Roger Dooley

- Sheena Iyengar

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week will be known to most of our listeners. More than 10 years ago, he wrote a bestselling book that argue that even though we think of more choices and more options as a good thing and even a goal to strive for, that prefer of choice may be counterproductive. His TED talk on the topic has been viewed more than seven million times. He’s a professor of economic psychology at Swarthmore College and the author of the hugely influential, The Paradox of Choice: Why Less is More. Welcome to the show, Barry Schwartz.

Barry Schwartz: Hi, Roger. It’s a pleasure to be with you.

Roger Dooley: I’m really excited to have you on the show, Barry. I’ve saw you do work frequently on my own advice to marketers. A while back, I wrote an article, The Purple Oreo Problem. When I wrote that article, I was able to find 57 different kinds of Oreo cookies on their website with double stuffing, with peanut butter, mini sizes and among many other options with purple stuffing, do we really need Oreos with purple stuffing?

Barry Schwartz: Just what the world needed.

Roger Dooley: A lot of the work on choice seems to stem back to the famous Columbia jam experiment. That seemed counter intuitive because just for our listeners who aren’t too familiar with it, various shoppers were given a choice of three jams or a couple of dozen and surprisingly more jam was sold when there are only three choices even though it seems fairly logical that if you have that blueberry-strawberry combo, that might appeal for somebody more than the simple varieties that are available. Lately, it seems like that study has been called into question. At least, folks have tried to replicate it in other ways and haven’t always succeeded. What’s going on there?

Barry Schwartz: Right, I think there’s a fair amount of misunderstanding about this. There was a big study that got a lot of attention that looked at all the studies that had been done where the number of options was itself manipulated to see how reliable this too much choice effect was and the summary conclusion they came to is that on average the effect is zero, meaning it doesn’t matter how many options you give people but that actually was a wrong summary because you would get a bunch of studies where you did reproduce the too much choice effect where more choice produce less selection and a bunch of studies where more choice produce more selection which is what a standard economic analysis would lead you to expect.

If you average these two sets of studies together, the average result is that there is no effect but that mass effect that there are almost always effects in one direction or the other. We don’t quite know why, what determines whether you’ll get a paralysis when there are so many options or enthusiast. It’s still an active area for search but it would have been foolish for anyone to think that there’s any phenomenon on the social sciences that you simply get every time you do a study. It depends on, there are boundary conditions. We don’t know what the boundary conditions are.

One day, we will have a better idea of what the boundary conditions are than we do now but what, that jam study, the person who did the jam study, Sheena Lyengar, also looked at real-life data of employees’ contributions to their 401K retirement plans and she looked across many different companies where some companies offered employees a few options and some offered them dozens and some offered them over a 100. She found the more options the employer offered, the less likely employees were to choose any. It isn’t just jam which is after all pretty inconsequential.

When it comes to putting money away for retirement when you were faced with an overwhelming array of options, you end up basically saying, I’ll decide tomorrow and then tomorrow you say, I’ll decide tomorrow and you end up simply not choosing.

Roger Dooley: I guess that makes a huge amount of sense particularly on the retirement plan side of things since if you have that many options that requires careful analysis, I mean, jams, you can probably figure out if you like strawberry jams or peach marmalade or something but when it comes to comparing mixes of bond and equities and various amounts of risks and maturities, that sort of thing, I can see where that would be very hard for people to do and we know that people like to avoid things that are hard and …

Barry Schwartz: That’s right. Notice that many of these cases, employees were not getting matching money from the employer by not participating. In effect, they were lighting a match to a $5,000 check by deferring this decision. Yes, it is a hard decision to make but basically you can just throw a dart at the list and end up better off than you are by not signing up at all. Still, people were paralyzed.

Roger Dooley: Sure, that’s why they’ve done their work on choice architecture showing that if you pre-enroll somebody on a 401K and see if they opt out of it, it should give them a much, much higher compliance.

Barry Schwartz: It’s all the difference in the world.

Roger Dooley: I think difficulty is in fact important. I recall, one, very simple choice experiment where people were asked to choose between two phones, two cordless phones for their home. More than four out of five were able to choose between the two models. They’re fairly similar but had a few differences in their specifications but those same, similar subjects were presented with those same choices when the descriptions of the phone were put in a hard-to-read type font that was sort of an embossed italic font, not impossible to read but just a little more stressful then 40% were unable to make a decision.

You have this cognitive fluency effect where the difficulty in reading transferred into a difficulty into making an actual decision. I would guess there might be a little of that factor work too because I’ve seen some of these planned documents for 401K plans and they are far from easy going.

Barry Schwartz: It’s true but I think the thing is that it’s not just that some choices are intrinsically hard to make and others not. There are a lot of choices that don’t seem very hard to make but then all of the sudden you see a hundred options and everyone is different in some way from the others. All of the sudden, what’s not a hard a choice has become a hard choice because you have to figure out what makes them different from one another and whether one is marginally better than the other. It’s true, picking up an investment is intrinsically complicated although an index fund is probably not a bad idea.

You can make choosing a jam complicated when people see an array of 30 different flavors or choosing a pair of jeans when people see 500 different kinds of jeans they might buy online. Partly, what makes it hard is precisely that there were so many options that are almost indistinguishable from one another.

Roger Dooley: Barry, I was at Carnegie Mellon when Herb Simon was there. I didn’t get to study with him. I was an engineering student at that time although hardly enough, I did served on a committee with his collaborator, Allan Newell who actually bailed me out of a problem that I created at the campus post office as part of that committee work. I guess I ruffled a few feathers and he was kind enough to smooth things out. Herb Simon invented the concept of satisficing which you mentioned in your work. Can you explain that and how it relates to choice?

Barry Schwartz: He did this in the 1950s and it was essentially ignored ever after. The canonical economic view is that we are maximizers of utility and his argument was not that we don’t aspire to be maximizers of utility but that it’s simply too hard of a problem for our limited cognitive resources to solve. It’s just too hard. To build a model of choice that is rational and consistent with what we know about the mind, it’s more plausible to imagine that what we’re doing is looking for good enough and over time, out standards for what counts as good enough may rush it up slowly but surely and approximate look finding the best.

If all you’re looking for is good enough, all you need to know is what your standard is and whether a particular option meets that standard. The incredibly complicated calculations that go into computing what would maximize don’t exist anymore. His argument was not that this was a cognitive style but essentially that this was a cognitive demand imposed by our information processing limits. He wrote a couple of papers that made this point. it seemed to me utterly convincing papers but they just had no effect and then I came along 50 years later with my collaborators and look at whether it might also be a cognitive style so some people wants the best genes, the best cars, the best college to go to, the best 401K to invest in and other people just want good enough.

The argument that we made is that in an environment where there’s a lot of options, looking for the best is completely paralyzing and impossible. In an environment where there were only a few options, there’s not much difference between looking for the best and looking for good enough but in an environment where there are hundreds of options, the only way to know you’ve got the best is by examining every single alternative, that’s a life-consuming project. We wondered whether people might defer in the extent to which they look for the best or only look for good enough.

We created a scale that tried to assess this as an individual difference variable and what we found indeed that there was a whole distribution of scores on this little scale that we developed. People who scored at the maximizing end of things were more depressed, less happy, took longer to make decisions, had a harder time making decisions and were less satisfied with the decisions they made than people who were at the satisficing end of the scale. It looked like people who maximize may do better objectively but feel worse about how they do. We did this work about almost 15 years ago and it’s been followed up by various people and as with everything in the social sciences there’s controversy about whether the scale we created is the best possible scale for assessing.

Roger Dooley: Maybe it’s just good enough.

Barry Schwartz: Our view was that it was good enough. It was certainly not perfect. There is no accepted scale that everyone uses but there’s been a fair amount of research on maximizing and its effects on various things since we published our original paper. Our argument was not that people can’t do it but rather that people couldn’t do it because it ends up undermining their ability to choose and undermining the satisfaction they get when they do choose.

Roger Dooley: Barry, how does the population, at least in the folks that you surveyed break down into maximizers versus satisficers?

Barry Schwartz: We can’t really answer that question because the scale is continuous. There are a bunch of items and if you’re a satisficer, you mark one on the seven-point scale on each item and if you’re a maximizer, you mark seven, we just add them all up and divide by the number of items. There’s no magic point, let’s say an average of 3.8 on a seven-point scale above which you’re a maximize and below which you’re a satisficer. You can’t really divide the population. They mean for the people we’ve study is pretty much in the middle of the scale three and a half on a seven-point scale.

We find that there are virtually no gender differences, there are no education differences. There are no “intelligence differences” we used as a proxy for that SAT scores. The only difference we found demographically is age. Older people are more likely to be satisficers than younger people are but that’s the only difference we’ve been able to find. We’ve also now studied different cultures and the pattern of maximizing versus satisficing distribution looks the same in several European countries, in Beijing and in Hong Kong.

Roger Dooley: It seems like it breaks down not only so much by individuals but even by a particular topic or category. I know, I just went through process of trying to buy a new travelling laptop bag. I travel a lot and need something to carry my gear in. I found there were, it seemed like an infinite number of options on with variables, it had to be small enough to fit in airline compartments and under airline seats but it had to be big enough to hold my stuff, have sufficient organization to keep things straight, had to have a strap on the back so that it could fit over the handle of my roller board and on and on and on to the point where I probably spent totally eight hours looking at different options.

I went to a dozen of different websites and looked at dozens and dozens of products and ended up with a choice that I still feel I am, it’s probably not quite optimal where on the other hand, I think that if I’m buying a shampoo, I’m pretty much a satisficer, I can go on the supermarket and find something that looks like it will probably work and be done with it. Is that true for most individuals that everybody is a maximizer in some area and a satisficer in others?

Barry Schwartz: Surprisingly, nobody has actually examined that empirically but I think you have to be right. Nobody is a maximizer about everything and maybe everybody is a maximizer about something. I think that what our scale captures is your general tendency to be a maximizer. Some people may be indifferent about what restaurants they eat in and care enormously about what car they buy. Some people may be the reverse. Some people care about clothes. Some people care about electronics. I don’t doubt that if you’re a maximizer when it comes to buying luggage but you’re not a maximizer when it comes to buying hair care products, that’s perfectly plausible.

It’s hard to imagine you could get through a day being a maximizer about everything. Imagine going to the post office and spending an hour deciding which stamps to buy.

Roger Dooley: If you’re an philatelist perhaps you would.

Barry Schwartz: If you’re sending out wedding invitations and you somehow want the stamp to be an echo of the joy of the occasion but by in large you just get stamps, right?

Roger Dooley: Right, it’s a utility.

Barry Schwartz: Yeah, but I bet there are some people who will spend an hour going through all the damn stamps they could buy to find whatever they think is the perfect stamps.

Roger Dooley: No doubt, a lot of our listeners are marketers and they’re constantly trying to decide how many choices to offer customers and it seems like and relatively, simple products like a software offering or something that somewhere around three is pretty common, it’s sort of a good, better and best maybe with a super duper choice at the top to make the others look better and then again you’ve got folks like Amazon that basically offer infinite choice or for all practical purposes, it’s infinite. How should a marketer go about thinking about, do I need to offer my customers more choices or fewer choices?

Barry Schwartz: I think there’s, unfortunately, there’s no quick and dirty way to answer that question because as you just pointed out, it probably depends on the domain you’re marketing in. There’ve been a couple of studies that tried to look at this systematically and they found that the optimal number of options was between eight and 10. If you have fewer than eight, people might not find anything they like. If you had more than 10, you’d get the paralysis effect. That’s the sweet spot. I think it would be foolish to think that having discovered the sweet spot when you’re offering people choices of writing implements, you now know the sweet spot when people are buying cars or trying to decide where to go on vacation.

I don’t think there’s a general answer and I think the only way to find out in whatever domain you market in is to do the research, offer people differing numbers of options and then track what they do, see how much time they spend, see whether they actually end up choosing something, see how satisfied they are with what they’ve chosen. There might be a magic number when it comes to choosing software and a magic number that’s different when it comes to choosing cars and so on. You can’t just look up the answer to your question.

Roger Dooley: Sure, actually I suppose it can even vary by individual. I might obsess over that laptop bag but somebody else might basically look for something, that, hey, I like the way it looks. It looks like it will fit good enough, let’s go with it.

Barry Schwartz: Of course the nice thing about doing this online is that you could actually tailor the website to each individual who visits it. If you had information about what their choice preferences are. In a brick-and-mortar store, you have to study a large number of people and decide that the right number of carry-on electronic stacks to have in the store is eight, not 30, not three but eight. That will be too few for you. It will be too many for me but for the average customer, it will be the right amount. I think that’s the only way to find out. There’s a company that I can’t name, it’s a housing, they build housing developments, high-end housing developments all over the country.

Their standard procedure is you decide what model of home you want and then you go to the design center to outfit your house, tile, carpet, gate, everything, fixtures for your bathroom and stuff like that. The average home buyer spent more than 20 hours with the consultant outfitting the house and it was extremely expensive for the builder both in the salaries you had to pay to these consultants but also it took longer to build the houses because there were so many different versions of these houses being built so they decided just to save money on production and to limit options in most of the categories. They figured that it would make customers less happy but it would be justified by that money they saved.

What they found is that when you limit options, A, people who buy more upgrades not fewer and, B, they spent four hours not 20 and C, they’re more satisfied with the final product than they were when they had more options to choose from. These were all completely unexpected. They were willing to take a hit and confident that the hit they took would be smaller than what they gained in production efficiency and it turned out they didn’t take a hit at all, just the reverse.

Roger Dooley: That’s really fascinating and a great example of how reducing choice can actually have good outcomes. I go back to the days when you could order your perfect car when you went to a car dealer. If you weren’t buying a new car off the lot you could order one from the factory and check off probably, I don’t know, a hundred plus different options and if you want to be upgraded floor mats and a particular sound system and the trim package and just item after item. When the imports are to come in they couldn’t really do that because they were shipping from overseas so they tried to put together these packages. Ultimately, that ended up being a much more successful approach.

Barry Schwartz: It is basically what you said low, medium, high. The deluxe, the whatever, the intermediate category gets labeled and then the strip down one. You’re right, they transform the way cars gets sold but it also gives you a good illustration of what happens when you give people options. I’m guessing you don’t care much about what floor mats you have in your car. You probably never gave it a moment’s thought and now you get told that you have options in the floor mats and you have to choose one. Well, now all of a sudden you care.

They’re giving me a choice. There must be a right one for me to pick. Now there’s no reason why the fact that you’ve got an option should make the decision any more important to you than it was before. We just have this compulsion when people are giving us a choice opportunity to make the most of that opportunity.

Roger Dooley: Barry, how important do you think combination of choice architecture and user interface is in helping marketers help their customers deal with too much choice? In other words, many websites have tools to present and to narrow choices, present things in different ways and so on, that may offer the opportunity to make a really complicated choice simpler. Does that help do you think?

Barry Schwartz: I think it’s incredibly important. Digital marketing has created a problem that was almost inconceivable prior to digital marketing. Everybody now has a warehouse with infinite floor space and then they start creating tools to help solve the problem. So I think if you really gave people undifferentiated lists of the versions of something that you’ve sold, I just checked on Amazon and there are 20,000 different varieties of women’s jeans you can choose from. Imagine a list of 20,000 different options in jeans, you’d be in your grave before you got through the list.

You’d never have to choose any. So you have to structure the options and you can structure them by your best guess about what categories make sense, slim, skinny jeans versus not, by color or by what have you or you can let people tell you what’s most important to them and then just shuffle the deck so that the options they get presented a tiny fraction of the ones you actually have available are the ones that they say capture what’s most important to them. I think that any online marketer that does not do something like that is going to simply to vanish into oblivion because people won’t put up with unstructured infinite choices.

Roger Dooley: I know that one other area where I tend to be a maximizer is travel arrangements whether it’s finding sort of the optimal hotel in a city that I’m visiting or getting the right flights. I really tend to rely on the sites that allow me to narrow my choices dramatically and sort so I can at least clear out many of the choices that are irrelevant and then rank the remaining ones by one or two important variables. When it comes to the final choice process it’s relatively simple although it still seems to take me probably far too long but it turns what’s completely unmanageable into something that is at least doable.

Barry Schwartz: No, that’s exactly right. I mean, I’m less fussy when it comes to getting from point A to point B. I give infinite value to non-stop flight, direct flights. I don’t care how much they cost, if it’s a direct flight, I’m on it. I’m not interested in saving a couple hundred dollars and flying through three different cities. The nice thing of … The fault on most of the site I’ve looked at is to rank by price. The presumption is what people want is the cheapest flight and not the most convenient one. All you have to do is click a button and they’ll reorder everything in line with what your criteria are and that’s exactly the right way to do things.

They’re all arrayed but you basically, if you’ve made it clear of what you care about is the shortest duration of the trip from point A to point B. Then you’re going to look at the top three or four options and you won’t care about the other 30 that are there. That’s smart, it’s easy to do and it’s the way every online marketer ought to be operating and the poor brick-and-mortar places just cannot compete. They don’t have that kind of flexibility.

Roger Dooley: That makes a huge amount of sense. Barry, our listeners are mostly familiar with the fear of missing out or FoMO. That’s why you see so many e-mails in your inbox with subject lines like don’t miss out or only one day left. How do FoMO and choice interact?

Barry Schwartz: I think they interact dramatically and I think you see this most profoundly not in the domain that marketers are mostly interested in but when it comes to our social relations. I think that the difficulty that young people have in making commitments to other young, romantic commitments or in making commitments to a plan about what they’re going to do on Friday night is that the set of possibilities is almost infinite. They’re worried that they’ll commit to doing one thing and then some better thing will turn up and they’ll kick themselves for not being able to do the better thing. The idea is to basically hold fire and not commit for as long as you possibly can. The result is that people end up without ever having any plans to do anything.

I think fear of missing out is huge at least among young people. I think it’s less of an issue and it’s really I think a generational thing. For me it’s most painful to observe in the domain of romance and friendship. You see the big cities much more than you do, small towns there really is not much going on but in big cities like there really are just an infinite number of possible things you could do this Saturday night. Why not hold out until you get to do whatever is the best thing.

Roger Dooley: It’s sort of a bad combination of maximization attitude and a lot of choice.

Barry Schwartz: I just think that it pushes people to be maximizers. If you’re in a small town it’s ridiculous to be a maximizer. It just aren’t going to be that many options but once the number of options is huge, why not the best.

Roger Dooley: Right. I guess that leads into probably your best-known quote, good enough is almost always good enough. They seem to be really words to live by. We don’t always do it but it would make a lot of sense.

Barry Schwartz: I think they are. People don’t like it and especially young people don’t like it. We are sort of encouraged all along to have high standards not to settle. When people hear good enough they say, well you’re just settling. Notice the word just. Just settling means that you’re doing less than you ought to when it comes to this decision and so it has an incredibly bad reputation. I think that one of the reasons why older people are less likely to be maximizers then younger people is that they learn the hard way that good enough is pretty much always good enough.

What happens over time is that they relax their standards having learned that they didn’t need the best, that they got the eighth best and they had a wonderful time. It just takes all the pressure or most of the pressure off in lots and lots of decision making. It’s very hard to convince a 21 year old that they should look for a good enough job.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Barry Schwartz: The fact that you can’t even get that sentence out, they’ve already turned their backs on you.

Roger Dooley: Obviously, you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Barry Schwartz: Exactly, and then they say, you think that because you’re old and you don’t know how to take advantage of technology so for you this is all daunting, but for me, a master of the universe like me, I have no problem. Sometimes they say that out loud and I say, yeah, I think that must be true which explains why every college I know about has a psych services center that is bursting at the seams and can’t meet demand. You guys are doing such a good job managing your lives that roughly half of you are getting psychotherapized and that humbles them a little bit.

Roger Dooley: Right. Along kind of the same vein you’ve said the secret to happiness is low expectations. It seems that would get even more negative reactions.

Barry Schwartz: It does.

Roger Dooley: It seems like it’s a defeatist attitude.

Barry Schwartz: It does. It does. It does, and of course this was an overstatement. What I actually mean is that the secret to happiness is realistic expectations or modest expectations but it’s much more dramatic to say the secret to happiness is low expectations. What defeats us is expectations that are so high that almost no result can meet them. You get a good job but it’s not as good as the job you expected to get and you end up disappointed. There’s a cartoon from the New Yorker that I often show, of a young woman wearing a sweatshirt that says, Brown but my first choice was Yale.

Now if you go to Brown thinking you really would be happier at Yale, you’re not going to get nearly as much out of being at Brown as you would if you embraced it enthusiastically. I think having realistic modest expectations means that you will actually have experiences that meet those expectations and sometimes exceed those expectations and that’s often what we rely on to judge when the decision we made was a good one, not how good was it in absolute terms but how good was it compared to how good we expected it to be. If you have ridiculously high expectations, almost anything you experience is going to fall short.

Roger Dooley: Bring up the topic of college admissions, I think this is a problem that’s unique to people in the US. Probably our overseas listeners will find it strange but the angst that the students and families go through because in the US if you’re a reasonably competent student you probably have 3,000 or more choices of colleges and universities at various levels that you can go to. Obviously, this presents a major choice issue because again for that reasonably competent student, he or she could probably get into almost all of those except for a few dozen really selective schools that have crazy admissions numbers.

Probably there are dozens if not a hundred or two or more that would provide a really good education that would be satisfying, not just good enough but a very good education. But they’re choosing process is so difficult that it seems that students and families often fall back on screening criteria like the U.S. News rankings. So you end up with all its attention focused on a handful of top schools and so many choices really are ignored. Is there a solution for that?

Barry Schwartz: There is a solution. I wrote an article for The Chronicle of Higher Education about this some years ago but nobody thinks I meant it. No one takes it seriously. This is a symmetrical problem. Students choosing colleges and colleges choosing students. The extremely selective colleges are saying yes to 10% of the people who apply when at least 50% of the people who apply would do just fine. They are inventing distinctions so that it doesn’t look as though it’s basically a coin flip who gets in and does. It really is basically a coin flip but no one’s willing to admit it. My modest proposal is that schools should simply establish criteria by which you divide students into those good enough to succeed and not good enough to succeed.

Then you take all the students who are good enough to succeed, put their names in a hat and just pick your class at random. This depressurizes the college selection process for students because they need to be good enough, which isn’t as hard as being the best in their high school, and they need to be lucky. Students can do the same thing. You create an equivalence class, you have 30 schools, any one of which would meet my interests as extracurricular activities I like, is in the part of the country I like and then it should be a matter of indifference to them which of those 30 schools they go to.

Instead what they do is they try to invent distinctions that makes one of those 30 better than the others and then they put all their hopes on getting into that one and feel like a failure if they don’t. I think it’s catastrophic. I think it’s wrecking the way kids go through high school. I think they get into college and think it’s the end, it’s the finish line of the race instead of beginning. It took so much work for them to reach this, they just don’t have the energy to embrace what comes next enthusiastically, and it’s all chasing this ridiculous and false notion that there is a best school or a best student. We’re doing real damage to teenagers with the system that we currently use and no one is willing to take a risk and change it.

Roger Dooley: Right. We’re all familiar with the angst involved. I know a website called College Confidential and students and parents hang out there. It’s an extremely busy site and of course particularly busy in the month of March as decision day draws near. People are so invested in their top choice school and why it’s sad, I mean, obviously it’s good to have people enthusiastic but when you know that so many are going to be disappointed because everybody is choosing their same first-choice schools and nine out of ten or even worse numbers are going to be rejected. It’s tough.

Barry Schwartz: It’s very tough. It’s pointless. A very famous article published a half century ago introduced this notion of, that they called, The principle of the Flat Maximum. The argument was there are region distribution in this case say the distribution of quality of undergraduate institution or the distribution of quality of high school students. In a particular region of the distribution, the differences between students or schools in that region are smaller than the error in whatever measuring instrument you’re using so that effectively all the kids who are in this region are equivalent and all the schools that are in this region are equivalent. Then U.S. News comes along and decide, no, they’re not equivalent.

This one is number one and this one is number two and this one is number three and then everyone chases this false precision and feels defeated and disappointed if they don’t get into whatever is their number one. I think it’s bad measurement, it’s bad science and it’s terrible psychology to be doing it the way we currently do it. You’re right, as far as I know this is a unique pathology of the United States.

Roger Dooley: I did a speech in Australia a couple years ago and it was to higher ED folks and there I think they have 36 or 39 institutions of higher education. The thought of three or 4,000 was just mind-boggling to the folks I talked to there. There, most of the decisions were based on location, which were the closest schools as opposed to some sort of arbitrary ranking system. I could probably talk higher ED for hours but we are just about out of time so let me remind our audience that we’re speaking with Barry Schwartz, the bestselling author of The Paradox of Choice. You can find that book and his other books at Amazon and other sources. We will have links in the show notes to Barry’s books and you can find the show notes by pointing your browser or phone at RogerDooley.com/podcast and we also have a text version of our conversation there as well. Barry, thanks for being on the show.

Barry Schwartz: Thank you. Yes. Wonderful questions, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.