My guest this week is Susan Weinschenk. Susan has a Ph.D. in Psychology and over 30 years of experience as a behavioral scientist. She is the CEO of The Team W, Inc., and a consultant to Fortune 1000 companies, start-ups, non-profits, as well as the government.

My guest this week is Susan Weinschenk. Susan has a Ph.D. in Psychology and over 30 years of experience as a behavioral scientist. She is the CEO of The Team W, Inc., and a consultant to Fortune 1000 companies, start-ups, non-profits, as well as the government.

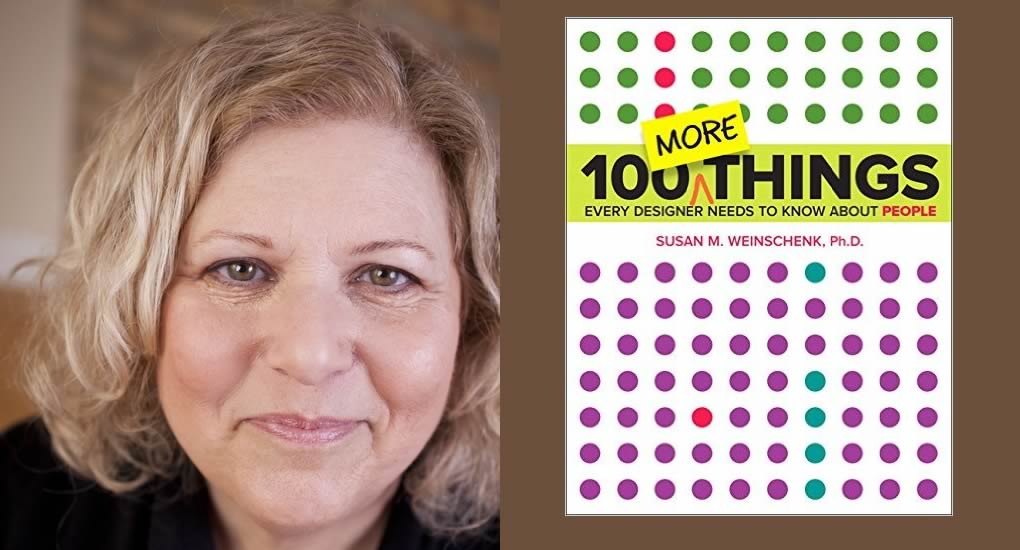

Susan’s nickname is “The Brain Lady,” because she applies research on brain science to predict, understand, and explain what motivates people and how they behave. She’s written several books including 100 Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People, and How To Get People To Do Stuff. Her book, Neuro Web Design, is one of my favorites.

Susan’s newest book is 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs To Know About People. She joins me today to share some of her research and the resulting practical applications that have been changing and possibly saving lives. Listen in to discover how you can learn to apply Susan’s research and alter the culture of your company for years to come.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast, and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why Susan’s transition from academia to the business world is so rare.

- Why Susan feels that researchers can’t simultaneously do research and interpret it.

- How Susan’s research helped an insurance authorizations department accept and incorporate software into their jobs.

- Why it is difficult to know where the ethical line for marketing is.

- The effects of storytelling and multichannel communication on your audience.

Key Resources:

- Connect with Susan: The Team W | Blog | Twitter

- Amazon: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs to Know About People (Voices That Matter)

by Susan Weinschenk

- Kindle Version: 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs to Know About People (Voices That Matter)

by Susan Weinschenk

- Nathalie Nahai

- Nir Eyal

- Amazon: Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal

- SXSW

- Dark Patterns

- Zig Ziglar

More at Amazon:

- Amazon: Neuro Web Design: What Makes Them Click?

by Susan Weinschenk

- Amazon: How to Get People to Do Stuff: Master the art and science of persuasion and motivation

by Susan Weinschenk

- Amazon: 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know About People (Voices That Matter)

by Susan Weinschenk

- Amazon: 100 Things Every Presenter Needs to Know About People

by Susan Weinschenk

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week has a Ph.D. in psychology and over thirty years of experience as a behavioral scientist. She’s a consultant to Fortune 1000 companies, startups, governments, and non-profits. Her nickname is “The Brain Lady” because she applies research on brain science to predict, understand, and explain what motivates people and how they behave.

She has written several books including 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People, How to Get People to Do Stuff, and her book, Neuro Web Design is one of my favorites. Her newest book is 100 MORE Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People. Welcome to the show, Susan Weinschenk.

Susan Weinschenk: Hi, Roger. Thanks for having me.

Roger Dooley: Before we get to the meat of our discussion, Susan, by the time the podcast airs it won’t really be secret that you and I, along with Web Psychologist Nathalie Nahai and Hooked author Nir Eyal, will be presenting at South by Southwest 2016 in March. Our panel is going to be “Hook ‘Em: The Psychology of Persuasive Products.” So I’m really excited by this, Susan. I feel like I’ve got the dream team of persuasive psychology on this panel.

Susan Weinschenk: It’s going to be so much fun but can we do more than just a panel? Because getting this group together seems like this momentous event. We should do something all day.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well, yeah, I don’t think South by Southwest is going to let us do that. They’re pretty strict about extracurricular, but I agree. Its fun to have such a great panel but the downside is the time that we each get to present is going to be very short. Nir was on my panel last year and he managed to do his hooked concept in about eleven and a half minutes, I think, which was probably as fast as he has ever done it.

Susan Weinschenk: Set a record.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, so that’s the downside. But on the other hand, I think that what we’ll probably do is try and allow as much time as possible for the folks in the audience to interact and ask questions. Then of course, they will be able to find us after the panel as well. So anyway, I hope that some of our listeners will be at South by Southwest and be able to meet you and me and Nir and Nathalie there.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: So Susan, you started off life as an academic. I found that lots of academics don’t really look at the business applications of their work. When they publish a paper, they’ll include a sentence in the conclusion suggesting some kind of hypothetical, real-world application, but to me it seems often this is just sort of a thrown in that makes their obscure research topic somehow seem relevant. It’s really rare to see them follow up on that and go out into the real world with say a business partner and try it out. So when did you think it would be a good idea to translate the work that you and other researchers were doing into something actually practical?

Susan Weinschenk: Well I have to admit that I really started out that way. I mean, right from when I was in graduate school, every time I would hear about some interesting research, I was always thinking ahead to wait a minute, what does that mean? Who should do what differently if that is actually true? Although I love research and always have and still do, I think there is a very practical part of me that is always asking, “Okay now, what would we do with that?”

Roger Dooley: Yeah that’s great. Although I guess I shouldn’t complain because the fact that all these other researchers really aren’t doing this work gives both you and me an opportunity to write books about it that actually takes their stuff and extends it into the real world. It’s a mixed blessing.

Susan Weinschenk: It is. But it’s an interesting point you make because sometimes people have asked me, “Would you like to be doing the research rather than reporting on the research?” I say, “Well sometimes, yeah.” In fact, I’ve done research at certain points in my career and really, really enjoyed that. But doing research is so intense, takes so much time and so much money. You really have to choose whether you’re going to be the researcher or interpret the research. I don’t think you can have a career at the same time where you’re doing both well.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, probably true, probably true. I think there are some folks that kind of bridge the gap but those are few and far between.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: I agree with you about doing the research because every now and then, I am not an academic or a researcher, but every now and then after studying a particular topic I think of some great concept that I would love if I had a few grad students at my disposal and a few extra bucks. Would love to turn them loose trying to answer that particular question. But that’s life. I do not have any grad students at my disposal.

So Susan, what is the first project that you worked on where you said, “Okay, this behavior science really can affect business results in the real world.”

Susan Weinschenk: Wow. That’s an interesting question.

Roger Dooley: I realize I’m probably delving back into ancient history here so if you want to pick a more recent one that you found particularly impactful, that’s fine too.

Susan Weinschenk: It’s hard for me to answer because there are … I have had a long career and there’s been, in all honesty, so many of them. I think one of the ones that really stands out for me as you asked that question is, I was doing work for a client that had some medical software. This was software that people used, it was the people at the insurance company who were doing pre-authorizations for medical procedures. They were using the software to decide whether something was going to be authorized or not.

It was interesting because the company you could either use the software or you could just call on the phone and get the certification. These people that worked at the company, they weren’t using the software. They were calling on the phone. So my job was to figure out why aren’t they using the software and what could we do with the software so that people would use it rather than use the phone.

We did some interviews with people and what came out was that they were so upset. They took this so seriously about the decision they were making. They knew that they were making a decision that might mean that someone would be cured or not cured or suffer or not suffer. So the emotional impact around it was affecting their wanting to do it on the phone.

We then had to figure out, how can we design this so that people will feel comfortable taking steps that have such a large impact? To me that was really interesting about the psychology and the behavioral science aspect of designing a piece of software.

Roger Dooley: Definitely. Then I think that one goes deeper than most but often those kinds of choices are influenced by rather simple user-experience things. In other words, people don’t use the software because they can’t figure out how to get into it or they can’t figure out how to get started or some other things that with relatively straightforward application of user-experience tools could be fixed.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah it’s interesting because the more you get to these emotional and highly critical actions that people are taking, then the more basic and simple the interface needs to be. Like the situation I described, when they’re facing making this decision, they’re under a lot of stress and we know that when people are under stress, they get tunnel vision and tunnel action. They just can’t handle things that are complicated and too much around them.

So you actually get kind of down to the real basics of designing a screen, or in a moment, or an interaction that has no distractions, is very clear. It’s almost like everything else gets stripped away and you just go to the real basics of it. So in this day and age of multiple screens and complicated interfaces and things not even happening on a screen but happening on other devices, which I deal with a lot, I kind of find it interesting that when we get down to the core of someone trying to do something and there’s that psychology behind it, all of that has to go away.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Susan Weinschenk: All the bells and whistles have to go away.

Roger Dooley: Right. Well that’s one of the basic principles of landing page design. If you look at conversion experts, who are actually in many cases, they may not have a Ph.D. but they’re rather brilliant experimenters.

Susan Weinschenk: They’re definitely behavioral scientists.

Roger Dooley: Right. All they do is run tests and then act on those results. Clearly, simplifying everything and taking away distracting elements and so on is just essential to maximizing conversion. But folks who aren’t in that business don’t get it. I’ve seen projects where companies are saying, “Why aren’t people using this?” And you look and there’s paragraphs of dense text and there’s images that don’t really relate to anything and links and other stuff going on. There’s just way too much going on there. Not only that, it’s disfluent. There’s a million reasons why it’s not good.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: One thing I’ve seen lately is that governments are kind of overtly using behavior science. I think that perhaps intuitively they always have but now you’ve got these nudge groups and whatnot that are trying to influence behavior of citizens. I don’t think that anybody would really would think that, say, getting people to save more for retirement is a bad thing. I mean, I think that probably anybody of any political persuasion would say, “Well, that’s a good objective.” Because you really don’t want people who get to retirement who have insufficient savings. But what if governments used it for things that were more controversial? You know, if their nudging effort was exposed and made to look like a partisan manipulation, do you think that could backfire?

Susan Weinschenk: Oh, definitely. I think that the line there is not clear at all. Oftentimes when I’m giving talks on the things that you can do and people do to influence behavior, it’s like, is it influencing behavior? Is it manipulating behavior? People ask me, “Where’s the line?” Where do ethics come into this? It’s a great question. I’ll just say I don’t have a good answer for it.

There are definitely some things that you can do that I believe are crossing an ethical line. Some of those are in the U.S. or even illegal to do. For instance, tricking someone into clicking on the checkbox that they didn’t notice and then by doing so they’re agreeing to some kind of ridiculous scam that’s going to wipe out their retirement savings. This happens, by the way.

I’ve done work as an expert witness for the FTC and there are internet scammers out there who manipulate the interface. When you press a button the screen gets covered up and you can’t see that they have automatically checked a check box, right? So that’s obvious, that’s not ethical. That’s scamming someone. That’s illegal, right?

But there’s lots of things that get done where it’s not illegal and it may not be as obvious but is it really okay? Whether that’s being done by someone who’s trying to sell you something or get you to sign up for something or whether that’s done by a government that wants you to save more for retirement. Or a local government that wants you to vote, whatever it is.

Roger Dooley: Right. Or they’re trying to get you to support their new, costly bond issue that’s going to result in a tax increase or something. Where then the farther you get from everybody agreeing that this is a good idea, I guess the more controversial it gets. There’s a great website which you’ve probably seen, DarkPatterns.org, that is full of examples of user interfaces that are manipulative and designed to produce a certain action.

Even one site that I’ve written about and others have written about is LinkedIn, which I like LinkedIn. I think it’s a great service; I use it probably nearly every day. But boy, they really do some sneaky stuff to get you to import your email contacts and some other things that is really–if their intent was more evil, it would really be sketchy. As it is, it’s merely kind of sketchy I guess.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah. Well, like I said, where’s the line? I don’t know. If a big box retailer is trying to get you to buy a refrigerator, is that … the advertisers have been trying to influence us for a very long time, decades and decades. Is that okay or not? I honestly don’t know where the line is. I really don’t. That’s definitely disturbing to me because I teach and talk about all of these techniques.

What I say to people is you have to decide. For what you’re doing and in the context you’re in, where’s that line and have you crossed that line or not? I don’t think that’s a very good answer but that’s the only one I have right now.

Roger Dooley: I too get asked that question all the time. Is this stuff ethical? My answer to that, which may not be fully adequate, but I use Zig Ziglar’s line because he was a master salesperson. He wrote books about twenty ways to close a sale that arguably were manipulative. You know, the presumptive close and all these sorts of things.

Susan Weinschenk: All of that, yeah.

Roger Dooley: But he said at least once, probably many times, that your most important tool for persuasion is your own integrity. That basically what I interpret that to mean is that if you were working to get your customer, or your citizen, or whatever, to a better place and you feel good about that, then it is probably okay. On the other hand, if you are manipulating them into doing something they will regret, that will not get them to a better place, the product isn’t a good product, or it’s not good for them, or whatever, then that is not ethical. But even there, you’re still having to draw some kind of line.

Susan, you and I both give speeches and presentations around the country, around the world, and a lot of our listeners I know are involved in speeches and presentations of all kinds. One of your earlier books is 100 Things Presenters Should Know about People. I’m wondering, what are a few of the ideas from that book that you have incorporated into your own speaking engagements? You can’t say all 100 because then I’ll make you list them.

Susan Weinschenk: [Laughs] I have the book right here. I could list them. No, I won’t do that. Well, let’s see. Some of my favorites are … I think everybody knows how important stories are in a presentation but I don’t think a lot of presenters know the brain science behind why stories are so important.

When you tell a story what we now know is that there are parts of your brain that are active when the listener is listening to the story. There are parts of their brain that are active as though they were having the experience that is in the story. So that means when I explain something to you by telling you a story about it, you’re going to get it. You’re going to understand it. You’re going to experience it. You’re going to remember it.

You’re going to react to it in a much different way than if I just give you data about something. That’s one of the things I think is so powerful to understand. It doesn’t just make it more interesting, it actually changes the way the brain processes and remembers the information.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. One of the great experiments involving stories used two fMRI machines. So this was a pretty serious experiment where it’s not just one but two fMRI machines with one person telling the other a story. The researchers found that the second person, the person listening to the story, after just a few seconds, their brain actually synchronized with the storyteller’s brain. So when I’m relating that to audiences, I tell them if you want to exercise mind control over somebody, telling them a story is about the best way to do that.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah, it’s really true. So that’s one of my favorite ones. I think another one that has to do with presentations that I talk about is about the fact that we are multichannel in many ways, right? We can listen and see at the same time. However, if you overload that too much, then we’re not going to be paying attention.

So if you’re showing me something on the slide and there’s movement and there’s animation going on while you’re saying something, it’s unlikely that I’m really listening to you anymore. I am probably just watching the animation. So although multichannel … when I say multichannel, I’m referring to the channel of the human, right? Multichannel is a good idea to do sometimes. You may want to watch out for that and you may want to alternate it.

A very simple technique that we talk about in presentations is that if you’re talking and there’s nothing to show visually, press that B button on your keyboard to blank out the screen. Sometimes people look at me and they almost want to gasp. Like, “You mean you could like have nothing on the screen?” It’s like, “Yeah, you could have nothing on the screen.”

I actually tell people when I’m coaching them on presentations, “Put together your entire presentation first without any visuals whatsoever. None. None. No visuals.” Then think about where in this presentation does something visual really add to it? We get so used to … it’s like our slides are our crutch. And they really are. Oftentimes when I look at someone’s slides that they’ve prepared for the presentation, it’s very aware to me that those are their notes [laughs].

Roger Dooley: Right.

Susan Weinschenk: They need them. They need them because they don’t know what comes next.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Susan Weinschenk: It’s like, “Okay, that’s your notes.” You can have notes. You don’t need to show the audience your notes. So to take that whole concept, to think about what if I gave this presentation with no visuals? It’s like okay, there’s certain things in it that would be really hard to understand if you didn’t see. It’s like all right, then that’s a good place to put a slide. Or even better, to use a prop. Not everything has to be a slide. Something can be a physical prop that you have with you.

I’m reminded of some of the TED talks. There’s that one TED talk where the woman is talking about her experience having a stroke. She actually brings out on stage a brain. A real human brain. Now most of us probably can’t get a hold of a real human brain. But you know, you could get hold of some kind of an anatomical brain if you were ….

Roger Dooley: Or a model of some kind, yeah. Although a real brain would be impressive.

Susan Weinschenk: Oh, it was really impressive. You could hear the audience [makes gasping sound]. Because it was a real brain.

Or about another TED talk where the speaker was talking about the impact on the environment of certain kinds of food and he was pouring from a bottle into these glasses this oil, kind of ugly, viscous thing. He was, “How much oil does it take to make …” He had a hamburger. He puts the hamburger up there. A real hamburger.

“How much oil does it take to make this hamburger?” Then he’s pouring this oil into these glasses and it’s not one glass, it’s not two glasses, it’s not three glasses, right? So to have props like that instead of visuals, that can turn your presentation from an interesting presentation to an unforgettable presentation.

Roger Dooley: Yeah Bill Gates and his mosquitos comes to mind too when he gave his famous talk about malaria eradication.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure that everybody who was in that audience had a sort of visceral memory of that part of his talk.

So let’s move on to your new book, Susan. One thing I like about it is probably because it’s kind of similar to my own Brainfluence book is that you’ve got a hundred bite-sized chapters that include both the basis in science and then some business takeaways from that, which I really like.

I think that it makes the content very accessible to readers who don’t have to plod through sort of lengthy exposition chapters and so on. They can focus on stuff that is interesting and relevant to whatever business problem they are trying to solve. You’ve used that style multiple times in your past books, what kind of feedback have you gotten about that?

Susan Weinschenk: I’ve gotten such positive feedback. The first time I did it I thought it would be a good idea. I thought it would be useful, but you know, I wasn’t sure. We got lots and lots of feedback about how absolutely wonderful that was. They love that it was in short bites. They loved that there were the takeaways. So then it was like, okay, I guess we’re going to repeat this. So we get lots of feedback that people really like the format of the books.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’ve had similar feedback. Obviously there’s certainly something to be said for the single big idea kind of book too. But those are often, I think, used less. They’re bought, put on a shelf. People get a chapter in or something and then quit.

Let’s look at just a few of the ideas from your book. I think we can probably talk about a few without giving away the whole book since there are a hundred, of course.

Susan Weinschenk: Right.

Roger Dooley: So I’m pretty used to bizarre research findings. Like I’ve written about stuff like the first letter of your last name influencing your personality and really kind of strange … but at least the scientists say, significant findings. But one chapter in your book involves ages ending in nine and how that affects the behavior of people. Like if somebody is 29 or 39, they behave differently. Explain some of the different ways that that affects people.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah. I found that one to be interesting too. The idea is that there are these certain years in your life and as you mentioned, they’re often the years ending with nine, in which you are more likely to take action on any number of things. The reason, the theory behind it is that we have in our heads, you know, it’s a big deal turning 40 or turning 50 or turning 60. So right before you make that turn you unconsciously starting to worry about things, think about things, some things are becoming more important. So because that’s kind of at top of mind or top of unconscious mind for you, you will be more likely than to take certain actions.

So you might be more likely to join a gym, right? Because you’re like, “Oh my gosh, I’m getting older. I better take care of myself and get more fit.” Or you’re more likely to go on a big trip. You might say, “Hey look, I’m not getting any younger. I’ve always wanted to go on that trip to New Zealand. I better go do it now.”

So the idea is if you know the ages of some of the people in your target audience, when you know they’re getting to these milestone years, that’s the time you would pitch those people. You would do the campaign to those people more strongly. Or make that a higher priority if you knew their age.

Roger Dooley: That’s really fascinating and sort of at first glance you might think when somebody turns 40, that’s when they’re going to have their … or 50 or whatever … when they’re going to have their mid-life crisis and go out and buy a sports car or join a gym or, I think as you point out in the book, join Ashley Madison.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: The dating site for basically cheating spouses.

Susan Weinschenk: Right.

Roger Dooley: But in fact it seems to happen in the nine years. I guess maybe it’s sort of maybe a scarcity, urgency type thing. Where time is running out on this part of your life so it’s necessary to take some kind of action that you want to accomplish. Either improve yourself or change your situation or whatever.

Susan Weinschenk: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, interesting. So cognitive dissonance is an interesting thing. Most marketers don’t exploit it. At least not intentionally. It’s not one of those things that you see recommended in blog posts. But you have a chapter about how marketers can use cognitive dissonance and sort of help customers resolve that. Why don’t you quickly explain what cognitive dissonance is and what the point is of that chapter in your book?

Susan Weinschenk: Cognitive dissonance, fancy term. It’s been studied for a long, long time in the field of psychology. The idea is that if we encounter a belief that is opposite to another belief that we have, that’s going to make us uncomfortable. We’re not going to like that.

So if I believe that I’m someone that likes to stay healthy and I like to eat healthy and that’s really important to me and then I realize at the same time that I’m someone that likes chocolate-covered doughnuts, this is a problem. We like to be coherent. We don’t like to feel that we have these two different things going on. So we’re going to take action to resolve that dissonance.

Now it could mean that we don’t eat the doughnut. It could mean that’s the action we take. It could mean that we start to change our view of, “Well, look, you know, of course it’s important to stay fit, but you know, you’ve got to enjoy life, right?” There’s all kinds of things we might do to resolve that dissonance.

Roger Dooley: There’s loads of research showing that chocolate is good for you too, so.

Susan Weinschenk: So that would be why you could say, “Oh yes, you know, I’m choosing the doughnut with the dark chocolate.”

Roger Dooley: Right. It’s health food.

Susan Weinschenk: It’s good for my heart, right? [Laughs] So what’s important in terms of how that affects our behavior when we’re buying something and in fact the section on cognitive dissonance, there’s two items of cognitive dissonance in the book, and they’re both in the chapter on how people shop and buy.

So one thing that’s important to understand is that just that when there is that dissonance, because you want to take action, if by buying something makes that dissonance go away, you are more likely to buy it. I think in the book I use, back to the gym membership idea.

If I’m someone who, if I believe that I need to take care of myself but if I also have just faced the fact that maybe I’ve gained some weight or I’m not in as good shape as I used to be, then I see this ad for gym membership, right? The gym membership could solve that cognitive dissonance for me. So you create and one of the things you can do if you’re a marketer is you can create the cognitive dissonance. Yeah, you can point out the fact that you’re not exercising and now it’s like, “Oh, I think I’m someone who’s fit but yeah, I haven’t exercised that much in the past year.”

So you create the dissonance and then you give them the solution. In fact, what a lot of marketing and sales is about is just that, although people may not realize that that’s why it’s effective. Then the other thing that’s really important about cognitive dissonance to understand is that people will commit… If I spend money on something, gym membership or I buy a new car, whatever it is. I need to feel that that was a good purchase. That I was a smart purchaser. That I did the right thing. People don’t like to regret the purchase they make.

If you can catch them right after they’ve made a purchase, that’s when they’re going to be the most likely to make a strong commitment to it. To write a testimonial, to give a review, to give a referral, right after they’ve bought it. Because if right after they bought it if they decided maybe it wasn’t a good idea, that’s going to create cognitive dissonance and they’re not going to like that. So they’re much more likely actually to commit to the purchase that they made and make a public statement about it right after they make it. It’s almost like they want to unconsciously … they want to stave off any feelings of regret.

Roger Dooley: Right. That makes a huge amount of sense. So let me remind our listeners, we’re speaking with Susan Weinschenk, behavioral scientist and author of the new book One Hundred MORE Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People. Susan, how can folks find your content and you online?

Susan Weinschenk: Probably the best way would be to go to our website which is TheTeamW.com. That’s where you can find out about all of our books and our courses and consulting and everything else. Also I do a fair amount of blogging and you can get to our blog from there. Twitter is another way to follow me and that’s @TheBrainLady.

Roger Dooley: Perfect. Okay well and we’ll have links to The Team W and Susan’s Twitter and anything else we talked about during the course of this show on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/Podcast. Thanks so much for being on the show, Susan.

Susan Weinschenk: I enjoyed it, Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.