Have you ever tried to reason with an argumentative, emotional child? How about working with multiple groups to find common ground? Negotiating emotional situations can be difficult…unless you have help.

Have you ever tried to reason with an argumentative, emotional child? How about working with multiple groups to find common ground? Negotiating emotional situations can be difficult…unless you have help.

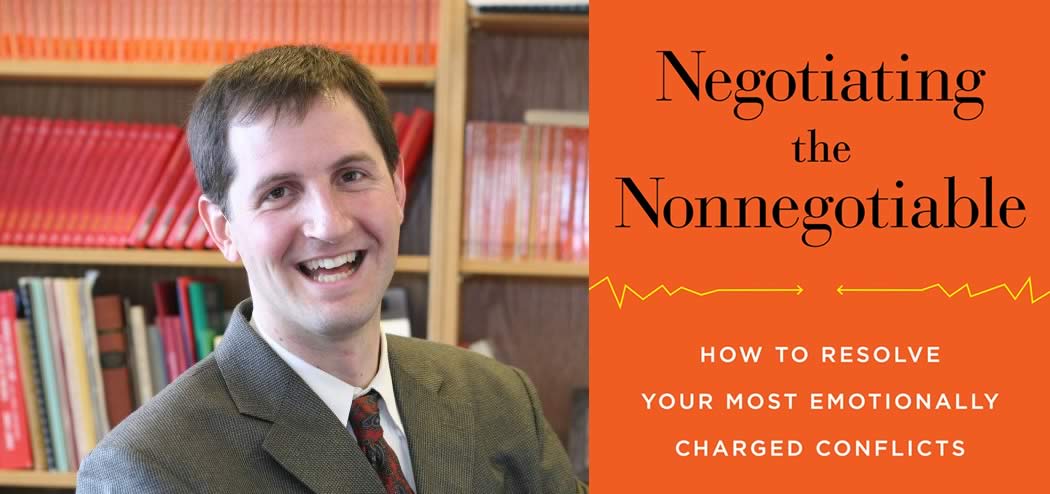

This week, I’m talking to our guest who is known around the world for his work in the field of negotiation and conflict resolution. Dan Shapiro founded and directs the Harvard International Negotiation Program, which focuses on the human dimensions of conflict resolution.

Dan has spent twenty years unraveling the mystery of what causes human conflict. His research has shown that rational approaches rarely work because most disputes hinge upon two non-rational forces: our emotions and identities.

Dan’s new book is Negotiating the Nonnegotiable: How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts. I know you’ll love hearing from him because he sounds a lot like a neuromarketer.

His work has been helping leaders, politicians and Fortune 500 company executives to break through the taboos of inter-party communication. If you have ever encountered an emotional situation you haven’t been able to negotiate successfully through, then you need to listen to this episode.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why emotional decisions should not be considered irrational decisions.

- How to have emotionally charged, yet rational, negotiations with your children.

- Freud’s theory on why we cannot ignore the loudest emotions.

- What Dan shows from a simple failed exercise with leaders at the World Economic Forum.

- The key insights of negotiation that you need to know.

- How to break the taboos of political parties to encourage communication.

Key Resources:

- Connect with Dan: Dan Shapiro Global | Harvard International Negotiation Program

- World Economic Forum

- Henry Tajfel

- Amazon: Negotiating the Nonnegotiable: How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts by Daniel Shapiro

- Kindle Version: Negotiating the Nonnegotiable: How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts by Daniel Shapiro

- Amazon: Beyond Reason: Using Emotions as You Negotiate by Daniel Shapiro and Roger Fisher

- See also Chris Voss on Negotiation

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by Leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. My guest this week is world-renowned for his work in the field of negotiation and conflict resolution. He founded and directs the Harvard International Negotiation Program, which focuses on the human dimensions of conflict resolution.

He spent 20 years unraveling the mystery of what causes human conflict. The reason I thought you’d love to hear from him is because he sounds a lot like a neuromarketer. His research has shown that rational approaches rarely work because most conflicts hinge upon non-rational forces: our emotions and identities.

His new book is Negotiating the Nonnegotiable: How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts. Welcome to the show, Dan Shapiro.

Dan Shapiro: Thank you so much. It’s great to be here.

Roger Dooley: Great, just a point of clarification for our listeners, you are the Harvard professor Dan Shapiro and you have a viewpoint on resolving Middle East conflicts but you are not the U.S. ambassador to Israel of the same name, right?

Dan Shapiro: This is true. Yes, this is true.

Roger Dooley: Okay. I hope nobody will be disappointed but I think that your viewpoints will probably be much more valuable to this particular audience.

Dan Shapiro: Sorry to interrupt you already but actually a few years ago when the ambassador was appointed, you would Google “Daniel Shapiro.” You got his picture with my bio. So it was something that neither of us wanted.

Roger Dooley: I have an even stranger story. For years, if you Googled me, I was pretty well the only Roger Dooley you could find. There’s actually a real psychologist, I think in Australia, which had to be very distressing for him to find me as sort of a faux practitioner of neuroscience and psychology dominating the results.

But a couple of years ago, Marvel and Disney came out with a character named Roger Dooley in one of their TV shows. So now I end up with Shea Whigham’s picture and it’s pretty strange.

Dan Shapiro: That’s great.

Roger Dooley: Unfortunately, that’s tough competition too in Google.

Dan Shapiro: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Dan, in reading the premise of your book, I was struck by its similarity to what I talk about a lot in marketing. The decisions are driven by emotions and non-conscious forces so that marketing that’s focused on rational decision-making often doesn’t work even though most marketers try and focus on features and benefits and price. Your work has shown that the same is true of negotiation.

Dan Shapiro: Yeah, absolutely. I was just giving a workshop last week in Switzerland. I had a questionnaire I gave out to everybody in advance. One person wrote back, “How do you deal with irrational people?” The interesting thing about this was that this person spelled irrational—because this person, English wasn’t their first language—so they spelled irrational “e-rational.”

What struck me is that E could stand for emotion. I don’t think that emotions are irrational, meaning there’s no logic or pattern to them. Every emotion has its logic to it. In a sense, there’s e-rationality as well as rationality.

Roger Dooley: I think you’ve got the title of your next book there, Dan.

Dan Shapiro: It might be actually. I’ll have to give you credit for offering the idea of it.

Roger Dooley: Somewhere buried in the acknowledgments.

Dan Shapiro: Yes.

Roger Dooley: Of course, the question about dealing with irrational people is kind of amusing because in one sense, we’re all irrational people. Although presumably some are a little bit more rational than others.

Dan Shapiro: Yes, exactly. I think it’s often the case that in a conflict or difficult negotiation each side believes the other is more irrational than they are. “I’m rational. You’re not.”

Roger Dooley: Of course, well simply because you’re holding viewpoints that don’t make sense compared to my correct ones.

Dan Shapiro: Exactly.

Roger Dooley: It seems like negotiations though are kind of rational processes. I mean, you’re trying to decide things like wages and work rules and national boundaries or whatever you happen to be negotiating. It seems like this is all sort of very rational, cognitive kind of stuff versus emotional. Where does the emotion come into it?

Dan Shapiro: I think that is often the assumption that negotiation is a rational game or a rational battle. I think it’s anything but the truth. I think the reality is first we are negotiating all the time. Any time you are interacting with somebody else, whether it’s with your spouse over where to go on the holidays or whether it’s with a team trying to negotiate a corporate strategy, you’re negotiating any time you interact for a purpose.

If human beings are negotiating with other human beings, inevitably, emotions will be a part of that. It’s my belief that you cannot avoid emotions any more than you can avoid thoughts and thinking, dreams at night, you can’t turn it on and off. Much of my research has really been about how do you channel emotions in a positive direction so that they work for you in a conflict and a difficult negotiation rather than working against you.

Roger Dooley: What you’re really saying is it’s better to not try and take emotion out of the process because that could be one approach. Remember, boy, the pop psychology thing from years and years ago, transactional analysis, where you had the parent and child.

The adult was always trying to kick things into a rational mode of stifling the childish outbursts or the rule-based parenting and communicate in a very rational way. But what you’re saying is you are not going to take emotion out of the process. You have to figure out how to work with it.

Dan Shapiro: Even that parent who’s trying to communicate in a quote/unquote “rational” way, you used the word “stifling.” They’re still experiencing emotion. They may not be expressing it very explicitly but they’re still feeling a tremendous amount of emotion. The question is how do you have that emotion work for the parent, work for the child, in that negotiation.

There was a story by Freud many years back. He talked about a professor teaching in a class. There was this really noisy, loud student in the front. The professor finally kicks the student outside the door, locks the doors, continues teaching. However that student outside starts banging twice as loudly on the door. The teacher still can’t teach. I think that’s the reality of emotions. You cannot get rid of them. You can’t avoid them.

In reality, we don’t want to. Whether it’s neuromarketing, neuro-influence, or just plain old dealing with your spouse.

Roger Dooley: Right, there’s a lot of overlap. I talk a lot about persuasion and that could be in a sales context or marketing context or whatever but there’s a huge overlap with negotiation there. You conducted a social identity experiment, I guess I’d call it, at Davos. Tell me about that. That was really a hilarious story. Hilarious, but serious too.

Dan Shapiro: Exactly. A lot of my work over the years has been in international conflict situations. I’ve been working to develop exercises to help people experience really a microcosm of those challenges. There’s an exercise that I’ve developed over time, I call it the Tribes Exercise. Basically, I just sort of make it come to life. Davos, at the World Economic Forum in Switzerland, way back in 2006 I was invited to do this little exercise there for all of these global leaders who were convening for the annual conference there in the mountains of Switzerland.

We had 45 people in our workshop room, everybody from a deputy head of state, leading academics, CEOs of Fortune 50 companies. As they’re walking in the room, they’re divided into six different tables, about eight people per table. I tell them, “You have this wonderful opportunity today to create your own tribes at your table. To create your own group identity in a way. Something that you feel emotionally invested in.” Because with my beliefs that I believe our world is becoming more and more of a tribal world.

They’re looking at me like this is fine, this sounds interesting, whatever. I say to the group, “You’re going to have 50 minutes now at your table to answer a small set of questions through full consensus and true to your own belief system.” They’re nodding, this is fine, this is fine. Until they look down at the questions and they realize these are some of the most morally difficult questions the world has ever seen.

“Does your tribe believe in capital punishment? Yes or no?’”

“Does your tribe believe in abortion? Yes or no?”

“What are the three key values of your tribe?”

“Dress up like your tribe.”

I give them balloons and things like that. They say, “Fine, we’ll try this little thing out for you.” They go off for about 50 minutes, they answer all these questions. They come back. You see now six distinct tribes. The deputy head of state has balloons on his head, others do too. Crazy outfits. It’s a very energizing environment. The music is loud.

I get in front of the room and I say in the most boring voice I can muster, “Okay, let’s debrief this exercise.” They look at my somewhat blankly, like, “Okay, what’s the point of this?” It’s right about this moment that the lights in the room go completely black. Into the room bursts this intergalactic alien. Huge bulging eyes. Huge head.

The alien says, “I am an intergalactic alien. I have come to destroy the earth. I will give you one opportunity to save this world from complete destruction. You must choose one of these six tribes to be the tribe of everybody. You cannot change anything about your tribe, or yours, or yours, only one tribe with all of its attributes must be decided upon. If you cannot come to agreement by the end of three rounds of negotiation, the world will be destroyed.”

Out floats this alien and as ridiculous as this sounds, these global leaders in our room suddenly realized we have a task in front of us. We must come to a decision, an agreement.

Roger Dooley: I’m surprised they let you get away with that. That like security didn’t…

Dan Shapiro: Actually, the alien mask, I got it from a local costume shop. I sent it a week before. It was the day before the workshop, the alien mask still wasn’t there. On the day of the workshop, literally we have the top security people from the World Economic Forum, while there’re about 50 heads of state there, 500 top CEOs there from the Fortune 500 companies. And what are all these security people doing? They are looking for an alien mask.

Roger Dooley: Great. So did they save the planet?

Dan Shapiro: To make a long story short, the longer version is in the book. The short of it, round one, they try to have a rational conversation. It goes nowhere. Round two, the charismatic CEO attracts one person to his group. The others refuse. Round three, six people come to the middle of the room, one representing each group. It just so happens it’s five men, one woman.

There’s so much anger and frustration in the room. These men walk into the middle. They start yelling over one another. They start yelling over this woman who gets so rightfully enraged that she literally stands on her chair and yells, “This is just another example of male competitive behavior. You all come to my tribe.” One other tribe comes to hers and joins. The others refuse.

And five… four… three… two… one… boom. Our world explodes at Davos. I have run this exercise dozens and dozens of times with executives, business executives, students from Harvard, from MIT, Chinese diplomats, Middle East negotiators. With virtually no exception—there are a few—but virtually no exception, the world explodes again and again and again and again.

How do you make sense of this? Rationality is not enough. Even emotions are not enough. Because this is a very high EQ, emotionally intelligent, group. There’s something deeper at play. Negotiating the Non-negotiable, my book, tries to look into what that is that causes us, whether it’s in that exercise or in real life to make our relationships explode when rationally it makes no sense.

Roger Dooley: In some cases at least, the group of people that you’re working with is probably fairly homogenous. But by creating these separate social identities, I mean this is an experiment I guess worthy of Henri Tajfel who did some of the early tests showing how trivial differences that he could artificially create would turn people into extremely tribal beings.

I’ve used that to explain in part Apple’s success because so much of their marketing has been, even from day one, is how different they are. “We’re a tribe apart. We’re different than the other guys. We’re also superior.” From the 1984 commercial through the Lemmings through the PC guy and Mac guy and so on. They’ve emphasized it. It’s been very effective for them. They’ve turned their customers in many cases into not only loyalists but evangelists.

Dan Shapiro: Right.

Roger Dooley: That’s great if you’re building a brand but not necessarily if you’re trying to reach consensus between multiple groups.

Dan Shapiro: Exactly, or even within the brand. So what do the dynamics look like within Apple? I don’t know, I haven’t worked for them, but within almost any organization you start to get that tribal kind of behavior as well. It can help move the groups toward greater productivity. If it’s not managed well, you can have an implosion within your organization.

Roger Dooley: Sure. There’s a classic conflict between sales and manufacturing or staff and line.

Dan Shapiro: Absolutely.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it happens in every company. One, as soon as it hits some size where you can actually form tribes. It almost inevitably comes into play.

Dan Shapiro: I agree with you. I think it even can be at the interpersonal level. Again, the spouses who are in the midst of a conflict, it can start to feel in a way like a tribal conflict. At least in the way I see the dynamic because it’s still, it’s me versus you. It’s us versus them. There’s that division of identity. You are different. I am superior. We are adversarial. In the book, I give that the name, I call it the Tribes Effect. What I mean by that is that it’s an adversarial mindset.

It’s not just fight or flight but it’s a mindset that sticks. So you have the divorcing couple who are feeling animosity toward one another or within the organization, the same dynamic. It’s hard to unstick it.

Roger Dooley: Can negotiation, or the process of engaging in negotiation, trigger, even increase the Tribes Effect?

Dan Shapiro: It depends on how one frames the process. It can absolutely intensify animosity and us/them mindset. A lot of my work is trying to help people see that that mindset does not get you more value most of the time in the negotiation. It gets you less. It doesn’t help relationships, it tends to hurt them. It reduces the value that’s on the table.

Really one of the key insights of negotiation is how do you turn that other person from an adversary into a colleague, even when you’re dealing with contentious issues? How do you turn it so it’s not marketing versus research or me versus the colleague down the hall, but it’s the two of us facing the same shared problems within the organization?

Roger Dooley: So how do you do that?

Dan Shapiro: One practical piece of advice, ask advice. Rather than walking in and saying, “You know what Roger, this all your fault. Why did you do…” and blaming, you can try to shift the dynamic by doing something like asking advice. Look, we have a problem between us. We could spend all afternoon arguing back and forth. I don’t think that’s going to be very effective. What’s your advice on how we might deal with this situation? Simply by asking that question, I turn you from an adversary into a colleague. You’re not the problem anymore. I’m not the problem. It’s the two of us facing it, being the problem between us in a way.

Roger Dooley: Dan, have you ever tried to run your alien experiment with that in mind? In other words, there you’ve got this external influence, the alien who’s going to destroy the world. You’ve got these tribes that are so self-oriented and tribally-orientated that they are not cooperating. Have you tried to modify the experiment to implement this kind of thinking and does it actually work?

Dan Shapiro: Well, no I haven’t. First of all, people assume a lot about the us/them nature of their negotiation. Nobody ever thinks to negotiate with the alien for example. They automatically assume the alien is evil—well, it’s saying it’s going to destroy the world, so it might be. But at the same time, nobody ever has thought to really engage the alien and negotiate. “So alien, hey, we’d like to include you in our community. Would you be interested?” You don’t know.

Now, so there is still opportunity for creating a greater identity, even in the exercise as it’s run. At the same time, I sort of like to keep it the way it is because people feel very shocked when the world explodes at their own hands. The exercise in a sense helps people to see all of the constraints that move us toward us/them thinking. They have 50 minutes or 60 minutes to define their own small tribal identity. They have a much shorter amount of time to try and create a joint identity. They spend 50 minutes or 60 minutes again answering some of the world’s most difficult moral questions and they only have a short amount of time to try to find commonality between them.

The way I plan the seats in the exercise has an impact on the extent to which they feel close or distant to others. The fact that they’re wearing the tribal garb, they have their tribal sounds, all of this plants them in an identity in a short amount of time. An identity that is against the other. They don’t even notice most of this happening.

I don’t see it as an experiment as much as an educational exercise to help people become more aware of all of the factors that can lead a group or a business or a company toward either division and loss of value or toward, in a sense, a communal mindset and really value maximization.

Roger Dooley: What’s your take, Dan, on the rhetoric in this year’s presidential campaign? It seem like tribalism is rampant on really both sides, whether it’s Trump with his nationalistic appeal or Bernie Sanders sort of rallying the 99 percent, we’re going to take what the 1 percent have and spread it out evenly. Do we have a bleak political future? How are we going to get around this? Because of course we’ve seen the same thing happening in Congress with seemingly greater polarization and unwillingness to negotiate.

Dan Shapiro: I watch it and I cannot help but think of my tribes exercise. Within each party, between parties, it is like tribes competing against one another. Not even just competing but adversarial with one another. They fall right into that category of playing out the Tribes Effect, that us versus them thinking. Each trying to sabotage the other. I think if two people are stuck on a lifeboat out at sea and each tries to sabotage the other. They’re going to end up nowhere but dead.

It’d be much better if the two individuals work together and paddle to shore. I think cooperation might sound like an unrealistic proposition in this current political climate. I don’t believe that’s true. I think the best leaders are able to draw upon their platform to lead across the aisle and within their own parties.

At the end of the day, I look at it and I go, wait a minute, let’s say Democrats and Republicans. It’s like they’re two tribes from different planets. The reality is, no, you’re both part of the United States. In order for effective governance to happen, we do need to work together. How do we work to build greater affiliation within each party and between the parties? I think that’s essential. Even down to very practical things.

Just bringing back that old-fashioned Washington D.C. lunch where the senators sit down and have a private get-together between parties. That kind of stuff is incredibly useful for helping them to open channels to more effective communication.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think certainly it’s true in politics and in today’s politics but probably in other areas of negotiation as well where if one member of a group tries to sort of find those areas of commonality, others in the group will then attack that person and accuse them of being weak or somehow in league with the wrong side. In some countries, that person might end up meeting a fatal accident. But here certainly even, mostly in politics, but certainly in other areas, that person who shows flexibility will be attacked for that flexibility.

Dan Shapiro: It’s a huge risk. In Negotiating the Non-negotiable, one of the things I talk about is taboos. Taboos are social prohibitions. They are unwritten rules that prevent us from doing certain things or saying certain things. Democrat, don’t talk to the Republicans. Republican, don’t talk to the Democrat. Israeli, don’t talk to the Palestinian. Palestinian, don’t talk to the Israeli.

How in the world can you ever have peace in the Middle East for example if the sides cannot talk to each other? How in the world are we ever going to have an effectively operating governance system if the two sides of our government don’t talk to one another?

Now I agree with you, there’s a danger that one can get decapitated, at least politically by talking to the other side. There’s a taboo against it and there are social consequences, punishment, for actually doing it. That said, there are absolutely ways that one can create a safe space, a somewhat brave space, for people to have dialog.

Let me give you an example. About four or five years ago, nobody, and I say nobody and I mean almost nobody, thought that it was possible for Israelis and Palestinians to get back to the formal political negotiation table. My own thought was, “Well, if you don’t believe it’s even possible, you’re going to do nothing about it. And self-fulfilling prophesy, nothing will happen.”

I started thinking, “What can we do?” One of the efforts that I did was to put together a group of Israeli and Palestinian and international leadership under the umbrella of the World Economic Forum. We met in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt and we had a conversation. The topic of our conversation was on taboos. What are some of the major taboos stopping people from talking to the other side in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

We then had them within the safety and privacy of this workshop think through, “What’s the use of that taboo? What are the dangers of having that taboo? Do we want to break the taboo? How could we break the taboo?” It was an incredibly powerful session. Tony Blair was there and later gave a public statement that this really had an impact in helping to bring the parties back to the negotiating table some time later.

I think, yes, it is taboo for quote/unquote “sides,” Democrats, Republicans, to talk to the other side, even to talk within to some of the others inside. How do we create the safe spaces for them to have some of those conversations? Maybe it’s not in a public restaurant in Georgetown. Maybe it’s in a private setting at an embassy event or something where you can have some of these individuals get together, meet one another, look each other in the eyes. You build that affiliation that allows for trust, open information sharing. Ultimately, more effective governance to happen.

Roger Dooley: Probably a good way in general to negotiate would be to do as much as possible perhaps outside that public eye where you’re going to get immediate feedback on everything that you’re discussing. Because ultimately, some of the more successful negotiations really do involve compromise and they involve individual leaders often who are coming together and giving on important stuff that initially their supporters probably would not have gone for. But by spending that time separately, as you say, in a safe space, they can actually work this out.

Dan Shapiro: I agree with you. I mean, it’s attention. Because if the leaders meet in private and then come together and publicly announce an idea, there’s a danger that they might get revolt from the people. The Oslo Accords were done in private in the Middle East and once they were publicly announced, there was a backlash against them.

It’s the same as two CEOs or two leaders from different divisions within an organization. Those division or departments may not get along. You have the leaders coming together. They announce a new decision. The people go, “What? You talked to other side and this is what you decided and you didn’t consult us before doing that?” It’s a very tight rope to walk.

But I think you’re right that there is an importance in having some private conversation. You also need to think through how do you then engage the broader constituency in that conversation as well.

Roger Dooley: Well, sure, yeah. If you come to a conclusion that is going to be extremely unpopular, that creates its own issues.

Dan Shapiro: That’s right, exactly.

Roger Dooley: Do you have any other examples? I don’t want to leave this conversation on a negative note that basically the future of the world is in danger because even a guy in an alien mask can’t bring a small group of people together. You have any other examples of a successful negotiation that took into account the Tribes Effect and perhaps looked very difficult to solve at first but was ultimately resulted in an agreement?

Dan Shapiro: Sure. As another example, there was absolutely that Tribes Effect phenomenon happening in Latin America between Peru and Ecuador. There had been a long-standing conflict between these two countries over a small piece of land called Tiwintza. Each side claimed Tiwintza as theirs and theirs alone. Each side had their own historical maps to prove that they were right and the other was wrong. There had been war.

The U.S. State Department called this the longest-standing armed conflict in the history of the western hemisphere. In 1998, Jamil Mahuad was elected president of Ecuador. It turns out he was a student of mine at one point. He was a student of my colleague Roger Fisher’s at one point. He calls up our organization, he says, “Look, I’m the newly elected president. I’m about to meet with President Fujimori of Peru. How do I negotiate?”

One might say that this is trying to negotiate the non-negotiable. Why even try? But he was interested in trying. So the question then is what’s the advice? How do you shift it so it’s not that Tribes Effect, that adversarial mindset? How do you shift it so it’s not a hopeless situation? Just a couple pieces of advice that we offered.

One piece of advice was to walk in and when meeting with President Fujimori, don’t start by claiming your position and asking his. So, “Here’s our position, what’s yours?” That’s the classic approach and it’s classically wrong. A much better approach is what President Mahuad ultimately did. He walked in and said to President Fujimori, “What’s your advice? You’ve been president for eight years. You’ve dealt with four of my predecessor presidents. Practically speaking, what is your advice on how we might deal with this conflict together?”

Simply by asking that question, it reframes their relationship from adversaries butting heads to colleagues sitting side by side, facing the same shared problem. To make a long story short, that relationship was essential to what ultimately ensued. Ten meetings later, 77 days later, they came to a full and binding agreement that stands to this day. In fact, President Mahuad wrote a first-hand account of how he utilized some of our concepts in a book that we published a few years back.

The challenge really is how do you shift it so it’s no longer me versus you to being us against the problem. It’s not my wife and I—it’s not I’m the enemy and she’s the enemy. That’s going to be a terrible family dynamic. We have a shared problem, how are we going to deal with it?

Roger Dooley: Right. So really, Dan, you’re saying that same approach can work in negotiation or just discussion at any level, even on a one-on-one in a family situation or in a work situation. Just instead of giving your demand, you ask for advice on how we can do this. It may not always work but it’s certainly perhaps a better path than the other.

Dan Shapiro: It’s one tactic to try to build the affiliation with the other side. To break down that wall of division. So it’s not foolproof but my sense is in my experience in working with business leaders, hostage negotiators, international negotiators, it can be very powerful. At the end of the day, you enhance the amount of value that everybody gets out of the agreement.

Roger Dooley: I think you’re showing a little bit of vulnerability too which may be helpful in the process. You’re not saying that you’ve got all the answers, you’re opening yourself up a little bit where I think the tendency in that sort of thing is to be very strong and very closed.

Dan Shapiro: Exactly, that’s right. The Tribes Effect, that adversarial mindset, closes us down. It turns the relationship adversarial. Asking advice is one of many tools to try to open up and to build that connection with the other side. So there is vulnerability. At the same time, it’s not soft.

President Mahuad didn’t go in and say, “Hey, let’s become partners and I’ll give you all of your demands. I’ll concede on every count.” He didn’t do that. He said, “Look, let’s sit side by side, together, and figure this thing out so that it’s to each of our benefits.”

Just as another quick example, I recently was consulting for the CEO of a pharmaceutical company who came to me and said, “We have a potential merger.” This was a huge, multibillion dollar deal. What was the cause of the problem after talking with them for quite some time it became apparent it was the relationship between him and the CEO of the other organization. They just had a terrible, adversarial relationship.

We talked about some simple ways to try to break down that Tribes Effect mentality. Another simple tactic was to try to simply appreciate the other’s perspective. Now why was this other CEO being such a jerk? This pharmaceutical CEO’s perspective? Really sitting in the seat of the other side and understanding some of the very basic human motivations that were there softened the stance of this pharmaceutical leader and allowed him to ultimately gesture, use some open gestures, to reengage in a conversation. Those little things, those little tools, had a huge impact on a huge, huge deal.

Going back to your initial point, in negotiation, yes, there’s a rational element to it. But what do I believe to be the essence? How do you build that connection with the other side? How do you shift the dynamic?

Roger Dooley: Great, well that’s a good, positive note to end on. Let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Dan Shapiro, founder and director of the Harvard International Negotiation Program and author of the new book, Negotiating the Nonnegotiable: How to Resolve Your Most Emotionally Charged Conflicts. Dan, how can people find you and your content online?

Dan Shapiro: My website is www.danshapiroglobal.com. So, Dan Shapiro global dot com.

Roger Dooley: Great. We’ll link to that as well as your book and any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there as well. Dan, thanks so much for being on the show. I hope you get that whole situation in the Middle East resolved really soon.

Dan Shapiro: Thank you so much. It’s an honor. It’s a pleasure to talk with you. We’ll work on it and I welcome your thoughts on it too. We need a little “brainfluence” there.

Roger Dooley: Thanks.

Dan Shapiro: Thank you.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.