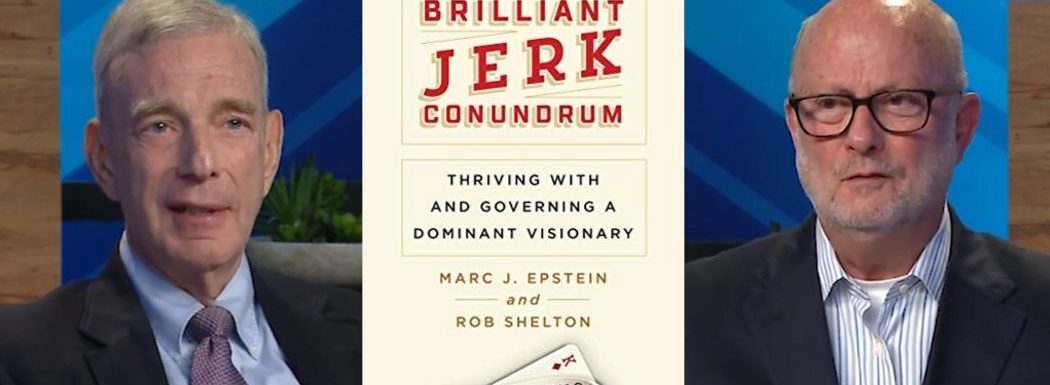

Marc J. Epstein and Rob Shelton are co-authors and thought leaders in innovation. Considered one of the global leaders in governance, performance measurement, and accountability in both corporations and not-for-profit organizations, Marc was, until recently, Distinguished Research Professor of Management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. Rob is a globally recognized Silicon Valley-based consultant, author, and speaker on entrepreneurial excellence.

The duo joins the show today to share insights from their newest book, The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum, on how to handle a person in the office who is very annoying and unpleasant—but also very good at their job. Listen in to learn how to know when to step in and redirect a visionary, the importance of an active board, and what to do if you find yourself working for a brilliant jerk.

Learn how to handle a person in the office who is very annoying and unpleasant—but also very good at their job, with Marc J. Epstein and Rob Shelton, authors of THE BRILLIANT JERK CONUNDRUM. #leadership #visionary #uber Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How to know when it’s time to step in and redirect a brilliant employee.

- The importance of putting a process in place for employees to be able to speak up.

- Whether becoming a CEO changes certain people.

- Why it’s crucial to have an active board.

- How to enhance employees’ ability to be creative.

- What to do if you find yourself working for a brilliant jerk.

Key Resources for Marc Epstein and Rob Shelton:

- Connect with Marc Epstein: LinkedIn

- Connect with Rob Shelton: LinkedIn

- Amazon: The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum: Thriving with and Governing a Dominant Visionary

- Kindle: The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum

- The Conundrum Press

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence, where author and international keynote speaker Roger Dooley has weekly conversations with thought leaders and world class experts. Every episode shows you how to improve your business with advice based on science or data.

Roger’s new book, Friction, is published by McGraw Hill and is now available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and bookstores everywhere. Dr Robert Cialdini described the book as, “Blinding insight,” and Nobel winner Dr. Richard Claimer said, “Reading Friction will arm any manager with a mental can of WD40.”

To learn more, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction, or just visit the book seller of your choice.

Now, here’s Roger.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to Brainfluence. I’m Roger Dooley.

Today, we’re going to talk about a topic that has probably affected all of us at one time or another, the person in the office who is annoying or even toxic, but also very good at his or her job. At the CEO level, we have the example of Travis Kalanick, whose relentless focus on the customer achieved spectacular growth at Uber, but whose management style created massive problems not just internally but externally as well. But most of these smart-but-problematic leaders never make front page news.

Joining me today to talk about how to deal with them, our two experts on the topic, Marc Epstein and Rob Shelton. Marc Epstein was until recently distinguished research professor of management at Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice university. Prior to Rice, Dr. Epstein was a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business, Harvard Business School, and INSEAD, that is the European Institute of Business Administration. Rob Shelton is a Silicon Valley based consultant, author, and speaker on entrepreneurial excellence, breakthrough innovation, and scaling to drive rapid growth.

Previously, Rob led the innovation practice at PwC and was also founder of PwC’s global Financial Service Innovation Center. Marc and Rob previously collaborated also with Tony Davila on the best-selling book Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from it. Their new book is The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum: Thriving with and Governing a Dominant Visionary. Welcome to the show, Marc and Rob.

Marc Epstein: Pleasure to be here.

Rob Shelton: Glad to talk with you.

Roger Dooley: Great. It’s been more than a dozen years since your last collaboration, how did you know it was time to get the band back together again?

Rob Shelton: Well, actually, we never stopped playing some of the music that we created when Making Innovation Work. We kept looking to see how things were progressing and changing and, importantly, to see some of the new things that emerged. One of them was the ascendancy of these very powerful dominant visionaries, like Steve Jobs. That led us to continue to explore what you do to be able to take advantage of the power these people bring to bring about important visionary change without them stepping out of bounds or otherwise affecting the value. So we continued to work together, but we only recently decided to put it all in a book.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, for starters, I’m curious, how you know when your hard-driving, brilliant visionary needs some adult supervision or a little redirection? Because you brought up Steve Jobs, he was later exposed to be a fairly toxic boss, wasn’t quite as evident when he was running Apple. But at the same time, it’s hard to imagine Apple being worth a trillion dollars if he had been reined in, if the board had said, “Okay. Well, we’re going to make you fix some of these things. You’re working people too hard. It’s not a good work environment.” Would Apple be what it is today? Maybe not, so how do you know when to step in?

Marc Epstein: I think, in part, that’s the conundrum, which is that, I think just as you described, what you want is you want to enhance their ability to innovate and be creative. And at the same time, organizations need to have some ability to control the behavior. Sometimes, as you described it, it does become toxic. I think one of the problems is that at Apple it was toxic for many years, and many people knew it. It’s just that what often happens in these organizations is nobody intervenes. Even though lots of employees understand the challenges in the organization and listening to someone who often rants and has erratic behavior, no one says anything. One of the things I think, one of the lessons is that, as employees, when we see things like this occurring, we need to tell somebody because often the board doesn’t take action because the board doesn’t know.

Roger Dooley: Maybe one of the most famous Steve Jobs imitators was Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos. She constantly was quoting him, she dressed like him, and she managed like him, except, of course, she ended up being in charge of a massive fraud. What’s the difference here, and how can you recognize? Because she even fooled her board members, it seemed, for most of the time. How you recognize when that person is actually driving the company to greater heights, and when they’re perhaps just snowing you?

Marc Epstein: Let me just respond a bit on Elizabeth Holmes. You say she fooled her board members, and that’s certainly true, but what you need in all of these situation is an active board. Just as I was mentioning, you need active employees who are involved. You need an active board. If you look at Elizabeth Holmes’ board, you had very famous people, Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, General Jim Mattis.

You had very famous people on the board who really didn’t have any expertise in either running public companies or in understanding blood testing. So though there was a stellar board in some levels, they were not active. They were not actively engaged in the business. No one was really looking into, does this technology, this blood testing actually work? They weren’t, in my opinion, even being diligent in their work as board members. So it was easy to fool them because no one was asking the tough questions.

Roger Dooley: Well, I guess there’s a lesson there. Of course, many of those folks were handpicked by the CEO herself, it seems like, so that practically ensured that they wouldn’t be too inquisitive. And, of course, board members tend to be rewarded very well for their efforts and the time they put in. I think there’s probably an inherent tendency not to rock the boat if it’s not necessary, particularly to aggravate the person who can probably get you kicked off the board.

Marc Epstein: It’s not necessarily desirable, but it’s common for board members to be picked in large part by the CEO. Even though there is a nominated committee of a board and that’s, as I said, not desirable, but what board members need to understand is, whether they’re being compensated well or not, they do have a very strong responsibility for strategic oversight. The Enron board was not doing that. To your point about copying Steve Jobs, yes, she copied Steve Jobs in the way she acted and dressed. But one of the big problems, obviously, is that Steve Jobs had a technology that worked great, and she did not.

Roger Dooley: Right, and which is why we remember him far more fondly than her now.

Rob Shelton: Yeah. But, Roger, let me add something to your comment, which is exactly right. We remember him more fondly than her, and also Marc’s description. Remember, Steve Jobs got fired once because he wasn’t producing the value that he could and in fact was destroying value with a bad culture and difficult obstreperous behavior. So even Steve, Steve 1.0 got fired, Steve 2.0 is the one we remember primarily. Thinking about this, we took a look at numerous dominant visionaries and the people that took the forefront with a vision and started a company or led it through important growth times.

But what we found is, building on Marc’s point, that the key to learning what kind of visionary you’ve got, and whether they’re going to be jerky, and just how brainy they’re going to be, is dependent in part on having a very diversified active board. But it also requires processes that the board puts in place. The Theranos board didn’t have them to find out exactly what’s going on and also to gather information on what the dominant visionary’s doing. As Mark pointed out, sometimes the board doesn’t know, but the responsibility falls on executives, and employees, and the board to make sure that information is available.

There are processes that allow information to flow up and be evaluated, and the decision makers become active and take some responsibility. This isn’t just to curtail a brainy jerk, this is to help a dominant visionary be successful whenever possible, but to help coach if there are areas where behavior is a problem. So the key is that the boards, the executives, and the employees that are most active and do this have a positive effect on helping the dominant visionary succeed. Those that don’t have processes, don’t get information, and don’t have activate executives and board members end up finding out too late. That’s the tragedy of the Theranos, and the Kalanick, and others that we’ve seen recently in the start-up world.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, and for our listeners who aren’t familiar with the Theranos story, I highly recommend the book Bad Blood that chronicles that, and it reads more like a thriller than a business book, excellent book. Here’s a little trivia point. My agent was also that author’s agent, and I suspect that that book has been far more lucrative for him than mine has been, my book Friction. Do you have some examples of visionaries who were just about at the point of having to be removed, or greatly have the responsibilities taken away, who were able to respond to coaching and did change their behavior so that they could continue?

Rob Shelton: I think one of the best examples of someone who received coaching is Larry Page at Google. Larry Page was a very young, brilliant person coming out of Stanford as a co-founder of Google. But it became clear that, because of his youth and lack of experience in the business world, that there were some gaps. While there was resistance on pupillary Page’s part, he listened, and they actually added a COO and ultimate CEO, Eric Schmidt, to fill in and to balance some of this. This is just one example of someone making a major change in their behavior.

Instead of him saying, “I have to be the one in charge,” he said, “Yes, I can see that going forward I’m going to need someone to help guide me.” They call this an adult in the room. What it really did was speaking to his young age, but the reality is, is what it did was fill a gap. This is one the most important things that a young dominant visionary or any dominant visionary can do, is to recognize that they need the guidance and help. There were other examples where dominant visionaries have been able to receive guidance from board members and executives along the way. I think everyone thinks that Steve Jobs was super headstrong and didn’t listen to anyone.

While he certainly exhibited those characteristics, he actually did have a couple of folks along the way. Mike Markkula, at the very early stage, was his mentor, was his coach, and played an important part in helping him think through and modify what he was planning to do. Later on, he found other folks on the board and amongst executives that could give him guidance. So there are examples of this happening and working. We don’t just have the train wrecks that occur, like Theranos or Enron. There are places where people take good guidance from people that they value and trust. The key is to make it something that’s built into the processes so that the dominant divisionary sees this as a standard operating procedure as opposed to an exception or a fire drill.

Marc Epstein: I think that if you look at Steve Jobs or Larry Page, as you suggest, or Mark Zuckerberg, these are folks that develop their companies when they’re in their early 20s, and Elizabeth Holmes also. So I don’t know why we would even expect that they would know how to run a company of thousands of employees. There are typically gaps in their knowledge and expertise that someone needs to fill, and this idea of an adult in the room is really critical.

Besides the Steve Jobs that you mentioned, Larry Page, Mark Zuckerberg bringing in Sheryl Sandberg very early on I think was a important element to the success of Facebook. Then we see the news of the last couple of weeks with Adam Neumann getting kicked out of WeWork. It’s amazing that here’s a company where he controlled the voting shares, founded the company, but his behavior got to be so outrageous that the board and the lead investors needed to step in and boot him out.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I was going to bring that up. That’s really an interesting situation because he clearly had this maybe sort of messianic zeal about what WeWork could be, but at the same time he seemed to be so unfocused on the important issues of building the company in a proper way. So much appeared to be for show rather than something that was going to lead them to a successful IPO. But at the same time, it had to be very difficult to take his vision and say, “Okay. Well, he’s not going to be part of the company now. We’re going to have to try and execute either on his vision or a new vision for the company.” Because it seemed like a lot of their value that they had been assigned was based on vision. It wasn’t based on numbers, that’s for sure.

Marc Epstein: I think your term messianic zeal is exactly right and applicable to Adam Neumann, but it’s applicable to many of these people. These are charismatic visionaries that are convinced that they’ve got something that’s going to change the world. And that’s great, and then it’s just a matter of the people around them need to constantly be involved in helping them with the governance and controls that are necessary to actually build a company. As I was mentioning a couple of minutes ago, most of these people don’t know how to build a company, and so it’s critical that you have these processes in place to do that.

Rob Shelton: I think it’s worth mentioning some of the characteristics that we’ve found when you look across the spectrum of these dominant visionaries that we’ve seen because we can focus in on their gaps, and that’s absolutely true. They do have gaps as well as brilliance. It’s their brilliance and their vision that makes them attractive to employees, to investors, to a whole host of folks. They are visionary, they’re game changers. They’re also powerful personalities that at one point can be a role model and then another time could be a jerk. They’re multivalent personalities.

They shift around, but they are powerful and not only in their vision and their ability to convince people, but in their commitment to making change happen. And that makes them tough taskmasters so that often they press on everyone around them to work as hard or harder than them so that they buy into and can bring about the change. But it’s also important to remember that in addition to this brilliance, and these gaps, and the forcefulness, these are inherently rule breakers. It’s important to bring that up because sometimes rule breakers will step over a line and go a step too far.

That means that there are ethical boundaries that can be crossed, or corporate cultures that can be created that are unattractive and ultimately unproductive. I think that’s what Neumann did. I think that’s what Kalanick at Uber and others have done along the way. Their strength is that they’re rule breakers and visionaries, but it serves as a problem as well unless they get the proper coaching and guidance, which brings us back to transparent interactive group working with these visionaries.

I think one of the biggest problems is that these visionaries get set up, or they set themselves up as a leader. People flock to them because of their magnetic personality and the vision that they have. Investors come in, everything looks wonderful, but people step back and say, “Okay. They’re in charge, let them go.” But as we’ve seen, that’s a formula for disaster. This idea that they can remain unattended, or unguided, or uncoached is not working very well. We have some successes, but in many cases we have some terrible failures.

Roger Dooley: Do these kinds of personalities exist in lower levels of the organization? Because I’m thinking most CEOs did not spring into life as a CEO, other than Mark Zuckerberg and a few others that went straight from college into a CEO slot. Does the normal corporate promotion process weed out some of these, or is this something that can actually develop where perhaps an individual is not quite as dominant or aggressive until they get into that CEO slot and then undergo a transformation?

Rob Shelton: That’s an interesting point. First, there are people that are jerks and brilliant all throughout the organization, and it’s important to admit that. We focused on those that are at the apex, the top of an organization, but without a doubt you’ll find them spread throughout. We both have personal experience with those that are CEOs as well as those that are in different positions. So, yes, they exist, but the process of growing employees and moving them up in the ranks doesn’t necessarily weed them out. This is one of the challenges these days is sometimes they’re in fact rewarded for their braininess, and the jerkiness isn’t addressed.

It does seem, however, that once someone attains a position of power, that some of the negatives can become more evident and visible. This is an issue for all resource management and HR departments everywhere, which is how are you going to make sure that you’re not growing your next brilliant jerk who could actually destroy value, and that you’re setting the tone inside the company for the right kinds of behaviors. Brilliance is always to be rewarded, but jerkiness isn’t. This is one of the challenges ahead for every organization.

Roger Dooley: I think in the finance industry is one where that can happen, where somebody is a great investment banker, somebody’s a great performer, and they’re leading an office or leading a part of the business, but their behavior is increasingly sort of off the charts. But because they’re generating the numbers, they get a pass, and then ultimately, of course, often comes to a bad end somehow or other. Either they end up crossing a line, doing something illegal, or getting sued or something of that nature. But up until that point, it can be certainly a difficult situation for those people who have to work with them or for them.

Rob Shelton: You’re absolutely right. I’ve had personal experience in the finance industry with that, but you should understand that it’s not limited to a given industry or even profession. You’re going to find them in sports. You’re going to find them in the medical profession. You’re going to find them in politics. It’s literally, this is a phenomena that exists everywhere. We focused in on the business community and didn’t pick out a particular sector, but just said this is something that happens here, but understand that this phenomenon occurs throughout any organization and across all modes of professionalism.

Marc Epstein: Yeah. It’s true in finance, as you suggest, Roger, but it’s also, you can find it in marketing and sales. You find it in a star salesman, a star marketing vice president. And even with his jerky behavior, the bosses may not want to do anything about it because the sales performance is so terrific. This is something, as Rob suggests, I think you have to be looking at the culture and the effect on the organization overall and often take action even when you have a star performer.

Rob Shelton: This brings up a very important point that this kind of behavior, the bad aspects of the behavior shouldn’t be allowed to happen, but they are. And this brings us around to sort of what culture is being grown or established in the company. There’s a common belief, and I think it’s correct, that culture eats strategy for breakfast. But there’s not a lot of attention paid to making sure that the culture, how shall I say, supports braininess but doesn’t allow jerkiness.

That helps people work at the highest possible level, but that makes sure that the ethical boundaries, the company culture are maintained even under the stress of rapid growth, or competitive challenges, or the things that happen in business. This is something that needs to be addressed, and it’s not just a board member issue. It happens in all levels of the company, and it’s something that every employee ought to be looking for a way to make sure that they’re a part of the positive aspects and not getting drawn into the negative.

Roger Dooley: What do you do if you find yourself working for one of these brilliant jerks? Whether they’re the CEO, and you’re at a fairly high level, or whether it’s part of the down in the organization, is there any hope other than just sort of living with it and hoping that it improves, he or she gets promoted, or or demoted, or something so that you no longer have to deal with that? Have you run across anybody who was effectively able to manage upward under those conditions? Because, I mean, certainly people always talk about managing upward, but it seems like managing upward when you’ve got a perhaps brilliant narcissist, egocentric person as your boss, it’s a lot tougher.

Rob Shelton: It is. The evidence that we picked up when we talked to people, we’ve interviewed a wide range and have been talking to people for many years, as I mentioned, this wasn’t something we thought of last week and decided to jump in. It’s been an ongoing area. It’s important to, one, have a way to not feel like you’re defeated if you run across someone like this. In some instances, employees actually create what I call a red badge of courage. They basically say, “Hey, you got nailed this week by this guy or gal. We had it last week.” So there’s a bit of commiseration about the fact that it’s going to happen. We’re all adults, and you just have to figure that there will be some of this.

The other thing is we found that the places that best, or where there was room to speak out, there was someone to go talk to and not just say, “Hey, there’s a problem,” and then somebody would bury it. But the feeling that somehow their voice got heard directly or indirectly, and that something was done. And that employees felt that they were a barometer for executives, a way to see how things were going, and that executives would mobilize, or the board would mobilize if necessary, in order to pay attention to this, to process the information and to take the appropriate action.

Again, some one-on-one coaching, annual review, making sure that something was communicated, that said some things are in balance and some things aren’t, keep doing these things, but maybe you should stop doing these. Those are important. I’ll add one more that sometimes people overlook, waiting for the system to solve your problem may not be sufficient.

You either need to be behind this person because they’re really good, and you can find a way to help them succeed either by living with their problems or helping curtail and coach them, or you should get out. It sends a strong signal if employees leave. People do pay attention to this. If a given person is actually causing the kind of rancor and disruption inside of an organization that’s corrosive, then people leaving sends a strong signal. It helps save the person who leaves from being beat up continually, but it also alerts the company that there’s a problem there.

Marc Epstein: I think too, just building on one of those points, because I think that it’s really critical for corporate governance, for boards to really have a process in place for employees to be able to speak up. Because too often, in all of these stories that we talk about in the book, the employees throughout the company knew about these instances, knew about the erratic behavior, knew about the toxic culture for a long time before it became public, and no one took action.

Often, the board just says, “We didn’t know.” And the board must know, and they must develop a process so that they will find out, and that is safe for employees to bubble up these concerns, and for then the board to be able to deal with it. That means collaboration with the CEO, talking with the CEO, working with the CEO, and then finding a way to solve the problem. Because too often, they don’t get solved until it’s too late, like in Theranos, or with Adam Neumann, or with Uber, and some of these other companies.

Roger Dooley: I think I probably add HR to the list as well because if something may not rise to the board level, but still I think often people have gone to HR with problems where… I mean, even looking at the Me Too stuff that is not directly part of this. But also the many instances where people’s complaints about harassment were ignored is, I think, a symptom of this where people see there’s a problem, they try and report the problem, but then it’s not acted on. Now, I think at least in the area of gender based harassment, that has been elevated somewhat where complaints will be taken seriously. But there’s really a whole host of behaviors that could be problematic here that you talk about in the book.

Marc Epstein: I agree.

Rob Shelton: I agree too. Now, I want to add something because we’re leaning in on this, or leaning towards the negatives. Certainly, that’s important, but remember that we need rule-breaking firebrands. They bring about a level of change that the traditional folks don’t. We need all types of people in the world, but these individuals that we’ve identified run a spectrum of success, admittedly. But importantly, they were in positions of power. They attracted store employees and investors. They have either led the charge for entirely new aspects of industry or even social change because of their vision, and that’s at the important part.

The issue is that it’s a mixed record to date. Not all of the folks that we can point to have been successful, or the level of success varies, and some have frankly crashed and burned. So what we have here is a situation that we’re trying to draw attention to that says you should create a way to have these dominant visionaries, these maverick rule changers be successful, or be sorted out without having to fire them in some last ditch effort to save the company, or because an IPO failed, or because there was malfeasance in financial reporting.

Those things shouldn’t be happening. Those folks should have been challenged and stopped well before it ever reached that critical stage, or they should have been guided towards their better side and the brilliance that caused them to hold that position in the first place, and support it as they were able to bring about change. So this isn’t just a case of stop the bad. It’s a case of find a way to deal with these individuals in a way that allows them to be successful and helps them, and curtails or protects against the downside risk.

Roger Dooley: I think that is a very positive note to end on here. Let me remind our listeners that today we are speaking with Marc Epstein and Rob Shelton, authors of the new book The Brilliant Jerk Conundrum: Thriving with and Governing a Dominant Visionary. How can people find you and your ideas, guys?

Rob Shelton: The best way is our website, theconundrumpress.com, or you can reach us via the email, [email protected].

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to there, to the book, and to any other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And as usual, we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too. Marc and Rob, thanks for being on the show.

Marc Epstein: Thank you very much.

Rob Shelton: Thank you.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Brainfluence. To find more episodes like this one, and to access all of Roger’s online writing and resources, the best starting point is RogerDooley.com.

And remember, Roger’s new book, Friction, is now available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and book sellers everywhere. Bestselling author Dan Pink calls it, “An important read,” and Wharton Professor Dr. Joana Berger said, “You’ll understand Friction’s power and how to harness it.”

For more information or for links to Amazon and other sellers, go to RogerDooley.com/Friction.