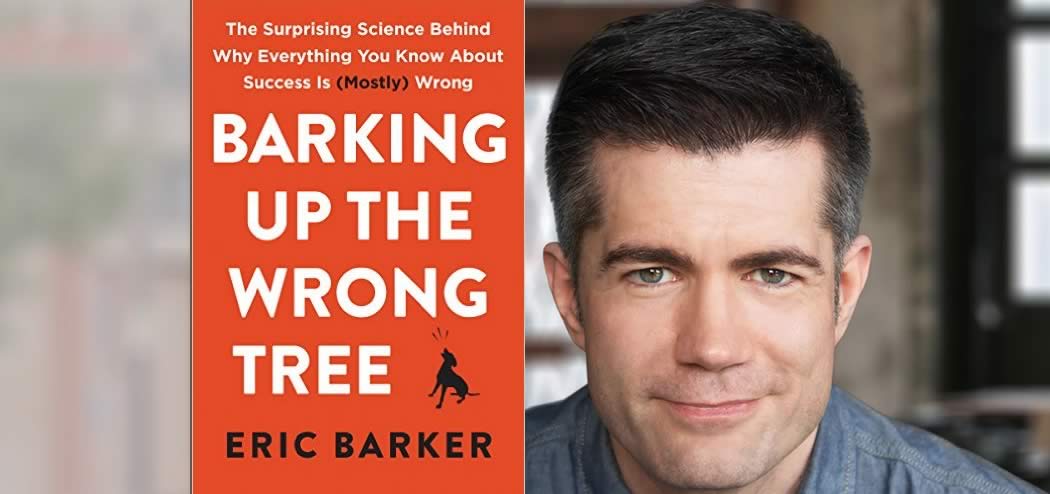

Eric Barker’s humorous, practical blog, Barking Up the Wrong Tree, presents science-based answers and expert insight on how to be awesome at life. His new book, Barking up the Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success Is (Mostly) Wrong, expands on Eric’s blog and breaks down common platitudes about how to be successful in life and business.

Eric Barker’s humorous, practical blog, Barking Up the Wrong Tree, presents science-based answers and expert insight on how to be awesome at life. His new book, Barking up the Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success Is (Mostly) Wrong, expands on Eric’s blog and breaks down common platitudes about how to be successful in life and business.

Eric is a a screenwriter-turned-blogger and much sought-after speaker and interview subject. He has been invited to speak at MIT, Yale, NPR affiliates, and on morning television.

In this interview, we discuss science-backed life hacks that people can actually use and our shared passion for well-researched productivity and life tips. We also talk about why you see super-generous people at both the top and bottom of the success ladder, and why those who are the top of the class in school aren’t always the most successful in life.

I’m positive that listeners of Brainfluence will feel a camaraderie with Eric and his blog!

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- What the data behind popular claims about success says about their veracity.

- Whether or not it pays to be altruistic or selfish.

- How Eric started his blog and finds life hacks and productivity tips that are actually supported by research.

- The best method for setting and attacking realistic goals.

- Why motivational visualization can actually be self-defeating.

- Tricks of the mind for avoiding bad behaviors and taking advantage of your brain’s natural laziness.

Key Resources for Eric Barker and Science-based Life Hacking:

- Connect with Eric: Barking Up the Wrong Tree Blog

- Amazon: Barking up the Wrong Tree

- Kindle: Barking Up the Wrong Tree

- Audible: Barking Up the Wrong Tree

- Dr. Gabriele Oettingen

- Smart Change: Five Tools to Create New and Sustainable Habits in Yourself and Others by Art Markman PhD

- Richard Wiseman

- Google’s Healthy Food Optimization

- Shawn Achor

- Dan Ariely: Website | Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

- Nicholas Christakis

- Bob Sutton

- Trust Factor: The Key to High Performance with Paul Zak on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Adam Grant

- Tucker Max: Website | Assholes Finish First

- Karen Arnold

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to The Brainfluence podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker, and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. I have a lot of fascinating guests on the show and many are authors, but it’s only occasionally that I say if you like my neuromarketing blog and my book Brainfluence, you’ll love this guest’s writing too, and today Eric Barker is one such guest. There’s a good chance you’ve read his blog Barking Up the Wrong Tree, which is full of science-based life hacks. He’s been writing it for eight years now and has finally come out with a book of the same name, subtitled The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know about Success is Mostly Wrong. Welcome to the show, Eric.

Eric Barker: It’s great to be here, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Eric, we’ve been acquainted for a few years, but I don’t really know that much about your back story. You were a Hollywood screen writer before you were a life hack blogger. What kind of projects did you work on and how did your interests evolve to where they are now?

Eric Barker: Yeah, I was a screenwriter in Hollywood for over a decade and it was a lot of fun. I wrote for Disney, I wrote for Fox, I worked on the Aladdin franchise. Basically I had a very unconventional career, so for me it was interesting, realizing that a lot of the maxims of success we have don’t apply universally. That was a big driver in terms of both my blog and my book, where I wanted some answers because I found the answers that were given when we were growing up don’t … you know, nice guys finish last. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know. Winners never quit, quitters never win. These are pithy and they’re easily spread, but they’re not necessarily backed by research or expert insight.

With the blog I went down the rabbit hole, looking at all the research, talking to the experts. Then for the book, you know, it’s I wanted these answers as much as anybody and I figured I’d share them as I was looking them up. Having a very unconventional career made me ask what really works, and that’s how I got started in both the blogging and the book writing sphere.

Roger Dooley: Well, your storytelling skill shows in the book, Eric, and congratulations on that. An underlying theme of the book is the common wisdom about what leads to success is if not usually wrong, at least often wrong. Let’s start with the valedictorian paradox. Certainly if you’re a valedictorian of your high school you’re destined for greatness, right?

Eric Barker: Actually, that’s not what the research shows. You’re destined to do well, there’s no doubt about that. You’re destined to do above average, but I think this is one that we all have scratched our head at, because we are bombarded of stories of Bill Gates dropped out of college, Steve Jobs dropped out of college. Not too long ago, a few years ago, Forbes did a research looking at some of the richest people, and what they found was that the … on the Forbes 400 list I believe of the richest people, the subset of those who dropped out of school had a higher net worth than the overall list. In fact, those who dropped out of school had a higher net worth than those who graduated from Ivy League universities.

That does create a paradox, where we’re told so often to study hard, and I’m not saying people shouldn’t study hard or shouldn’t endeavor to learn, but there is this paradox where we forget that school isn’t really about achieving the heights of success. School is largely about compliance, compliance with rules, and those rules are very clear. That’s what you see in the research that Karen Arnold did at Boston College, is that the people who become valedictorians are not necessarily the smartest. They are the ones who are the most compliant with rules. School has very clear rules.

Life does not have such clear rules. In life you can be an entrepreneur, you can be an artist. You can frame life the way you want and be successful, whereas in school you can’t. You don’t get to make up your own tests. At least in high school, you don’t get to make your own classes. You can’t do that, so life has many more options, many more permutations, so valedictorians succeed due to rigorous compliance with rules, and to some degree, gaming the system, whereas those who don’t want to comply, those who might be more creative, can struggle.

The people who are very passionate … a very clear irony is that we all know in life and your career, most people are rewarded for being an expert on a single subject, and school ironically does its best to prevent that, because you have to study English, you have to study history. You have to study math, and if you’re really passionate about math, sorry, you need to stop and you need to study history and you need to study English, whereas the working world doesn’t really care if you’re good at all the other roles at whatever organization you might work for. They want you to be really good at the one thing you do.

School rewards people being much more diverse, and the working world generally doesn’t, so in that way it can be actually a terrible preparation for what you’re going to see out there. Valedictorians certainly do well, but they generally don’t reach the heights of success. They usually fall into the system, become part of the system, rather than reinventing the system. You can see in other research that creativity is negatively correlated with reaching a CEO position because people who break the rules generally don’t survive the vetting process to get to the heights of success within most hierarchal organizations.

Roger Dooley: That all makes a huge amount of sense, Eric, and you can see where presumably great … not just good business success, but great business success often comes from breaking the existing paradigm, where high academic achievement is pretty much about excelling within the existing paradigm. I guess that brings me to the next point, and that is the good behavior versus bad behavior, and your conclusions are surprising there too. Coincidentally, I just recorded a session about 30 minutes ago with author and entrepreneur Tucker Max, who wrote a book titled Assholes Finish First. You’ve analyzed a lot of research on this and related topics. Do jerks really get ahead faster than nice people?

Eric Barker: You know, it’s a really interesting question because once again, we hear nice guys finish last, our parents tell us to be good. We all know some jerks who got ahead. We all know some nice people who got ahead, so there doesn’t necessarily seem to be clear answers, but when you look at the research, what you see if you look at the research from Adam Grant at Wharton, he was very surprised, because when he looked at the bottom, the people at the bottom of many success metrics, he saw the “givers”, the people who were very altruistic and went out of their way to help others, expecting nothing in return. They disproportionately showed up at the bottom of success metrics.

For Adam, who is a believer in helping other people, an incredible giver himself, this was very depressing, but when he looked at all of the data, he realized something really interesting, and that it was bimodal, that the givers showed up at the bottom of the success metrics disproportionately, but they also showed up at the top of the success metrics disproportionately, whereas the matchers, in other words, people who believed there should be an equal amount of give and take, and takers, the people who are the not-so-nice guys who are very focused on getting as much and giving as little as possible, they were clustered in the center.

What Adam realized is that for givers, for these altruistic, very unselfish people, very often they did very well or very bad. This jives with what I think most of us have seen, and that is we all know someone who is always thinking about other people, not thinking about themselves, basically becomes a martyr, gets taken advantage of, gets walked on, and they don’t do as well as they could, but we all also know people who are constantly going around doing favors, helping others, and everyone feels indebted to them. Everyone loves them and think they’re fantastic and returns the favor.

Roger Dooley: What’s the difference in behavior between these two groups, Eric?

Eric Barker: I was just going to say, is definitely there is a difference, where there’s a level of balance in terms of how much. One of the things Adam brings up is chunking versus sprinkling. The givers who do very well chunk. In other words, they will spend X percent of their time. They’ll spend one day a week or so many hours a month going out of their way to help others. Those people do very well because they still have a very good amount of their time to devote to their own projects, their own success, where versus sprinkling, this constant thinking about others, doing for others all the time, that interrupts personal projects and is very problematic for one’s own personal success.

On another very important, very important … and this is backed up by other research that was by Robert Axelrod, which was actually done around the time of the Cold War on the prisoner’s dilemma. Another key thing is that we find that matchers actually protect givers, because matchers not only try and balance their good behavior … that balance of give and take, there is often an ethic of believing that that there should be a balance. Therefore when matchers see givers being exploited, they don’t like this, and matchers will actually go out of their way to protect givers from takers.

What people can use to make this actionable is actually looking at the organization that they’re going into, looking at the people around them. Axelrod found that “good people”, when they are clustered, when they can work together … and even only a modest percentage, but maybe 10% are givers, they can work together quite well. There can be an enormous amount of value creation that can help and protect one another. But when givers are scarce, then they become easy to pick off for takers to exploit.

So if you’re going into an organization which is rife with the very people who want to exploit you, if you’re not connected to other givers, to matchers who will offer you protection, if there aren’t enough of them to be able to circle the wagon, then you can end up a martyr. But if you are chunking your time when you are helping others, if you gain the protection of matchers in your organization, if you’re connected to other givers who will be going out of their way to help you in return, then you’re in a good situation to be one of those givers who reaches the top of the success metrics as opposed to the bottom.

Roger Dooley: That actually ties a little bit with a conversation I had a month or two ago with Paul Zak. You’re well familiar with the oxytocin guy. He did a study of organizational trust, and I think wrote a whole book on organizational trust. I think that, although he wasn’t looking at it from the same dimensions that you just described, if you have an organization where basically you’ve got a very high percentage of takers, it’s almost certainly a low trust environment and it’s probably not the most pleasant place to work. Also it’s likely to be an underperforming organization as well because his research showed that where you do have a high level of trust in a group, that actually greatly increases the organizational performance. Not exactly the same slant, but I think somewhat the same conclusion.

Eric Barker: No, I think you see that a lot. Peer pressure is something we usually talk about when it comes to teenagers, but the truth is, when I spoke to Dan Ariely of Duke University, he said that one of the biggest insights that we’ve gained that is consistent throughout all of social science research is the importance of context, and we are dramatically influenced by our context, but the problem is that we don’t usually realize it because we all want to think that we’re independent. We all want to think we make our own decisions. To preserve our egos and self-esteem and to not feel like life is random, we want to feel like we’re in control, but the truth is that a good portion of our behavior, our decisions are influenced by our context, and part of that context is the people around us.

When I spoke to Bob Sutton at Stanford, he said the key piece of advice that he gives to all of his students at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford, is when you join an organization, when you’re interviewing, look around at the other people who work there because you’re going to become like them, they’re not going to become like you. If you feel like you’re a very ethical person and they’re very unethical, or even the reverse, it’s not going to work. You’re going to be in trouble.

Number on, you’re probably going to be unhappy. Number two, you’re probably not going to do very well, but the most dangerous of all is number three, you’re probably going to become more like them, so that’s something you really need to consider up front. When we delude ourselves that we are not influenced by those around us, that’s where things can get really dangerous.

If you look at the research by Nicholas Christakis at Yale, my God, the power of your friends’ friends, when they become happier, it’s measurable that you become happier. The networks among people are incredibly powerful and the ethical considerations are huge. So much of Dan Ariely’s research on cheating, on breaking the rules, just shows that organizations, much like you were saying, it ripples throughout organizations. All kinds of behaviors ripple throughout social networks. It’s very dangerous for us to not be cognizant of that.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, grit has been really popular as a concept for the last few years. You know, the ability to persevere despite difficulty has been declared as the ultimate skill, more important than IQ and some other factors that are traditional markers of success. But in the book you talk about quitting at times being just as important, so how do you know when to exhibit grit and preserve and keep on going, when to quit, and so on? I consider both are important.

Eric Barker: Yeah, both are essential, and that’s a problem we get into, is people obviously like simple easy answers. That can actually be dangerous because there are plenty of things that we can endeavor to be gritty at that we shouldn’t. Certainly many people have problems with sticking with things, being consistent, and that’s why we teach to learn so much about grit. On the flip side, certainly I’m glad I’m not doing the same things, you know, the same things that I was when I was five-years-old or when I was 15-years-old. You have to let go of some things, so first and foremost it’s critical to just realize the economics principle of opportunity cost, where you only have 24 hours in a day, period, and if you’re spending an hour at work you’re not spending an hour with your family, and that’s a choice.

We don’t usually like to think about life in terms of trade-offs because it’s not very fun, but just like if you spend a dollar on candy, that’s a dollar that you’re not putting into your savings account. The same is true with our hours, so we need to think, where do we want to double down? Where do we want to put those hours and where do we not? And quit is not necessarily the opposite of grit. The two can be quite complementary in the sense that the things that you quit free up more hours for you to spend on the things you want to be gritty at, so it’s really a complementary behavior there.

What becomes critical is once we realize that quitting things frees up time for being gritty, then great, but like you said, the question becomes how do we know what to stick with and what to not to? If we look at Gabriele Oettingen’s research at NYU, she came up with this really clever little acronym called WOOP, which is basically what we can use to figure out what is important, and the first step is to think about your wish. What are you wishing for? That’s the fun part, but the thing is that The Secret is not … and I mean the book The Secret … is not true. We can’t just focus on what we want to wish for, because that actually turns out to drain energy, because once our brains think we have something, we devote less energy to it.

So the first thing you do is you think about wish. The second thing you think about is the outcome you want, so what is the actual goal? If you want to get a job, what is that job? Maybe you want to be a VP at Google. Okay, fine. Now you have a crystal clear, it’s not just a vague wish. Then this is the critical part that most people fail at, and that is obstacle. You need to think about what is the obstacle that’s preventing you from doing that? That can be a little negative. It’s not so much fun all the time, but you can say, “Well, I don’t know anybody at Google who can get my resume up the chain there.”

The fourth step is a plan. How can I overcome this obstacle? Then you say, “I can go on LinkedIn and I can see which connections of mine know somebody in HR at Google.” Now you’ve gone from a wish, from the outcome, to the obstacle that’s a problem, and then you have a plan. Now what’s really interesting is not only does this get people from a vague wish to creating a plan by which that they can get where they want to go, but she found another really interesting thing, and that was that once people go through the WOOP exercise, if after doing it, if it’s a realistic plan, if it’s something that they should stick with, if it’s something that they should move forward with, people felt energized.

On the other hand, if people had an unrealistic wish, a wish that really wasn’t likely to come true or they weren’t likely to follow through it, they felt less energized. So WOOP is not only a way to build a plan, but it’s also a litmus test for is this something you should be gritty at or is this something you should quit? Because if at the end of the exercise, you feel like, “All right! Hey, let me get on LinkedIn, let me find that person at Google. I’m going to get my resume together,” then this is the kind of thing you should be gritty with. If it’s something like, “Oh my God, this just doesn’t even … I don’t know if I want to do it,” that’s a sign that maybe you’re not ready for that, that maybe this is something you should quit, and devote your grit energy elsewhere.

Roger Dooley: I think that’s probably consistent with a lot of advice from at least some productivity experts, about being very intentional with the way you spend your time too, because we all get sucked into things and we engage in activities that aren’t necessarily leading us to our goals, but we’ve always done them or it’s part of our routine and we just keep on doing them instead of sitting back and examining each and every thing. As you say, you can quit some activities to make more time for the really important stuff.

I want to jump back to something you said about thinking about your successful state not necessarily being a good thing. I would guess that probably two-thirds or more of the motivational coaches that I’ve heard will tell you to visualize your end state. If you’re trying to lose weight, they’ll tell you to visualize your thin self, or put a picture of the Ferrari you aspire to on the wall in front of you where you can see it all the time and so on. That actually can be self-defeating, according to at least some research, right?

Eric Barker: Yeah. Well, I think people confuse some of the ideas on visualization. When we hear the studies of the basketball players who actually practiced and improved, versus the basketball players who merely close their eyes while on the couch and visualize them performing a skill, you see that yeah, it’s like they’re comparable, but that skill training versus simply saying, “That’s something I want,” that’s very different.

The reason that movies and TV are exciting is because our brains are not great at distinguishing reality from fantasy. That’s why horror movies are scary. If you interpreted every horror movie as, “I am watching a flat screen and an image of pixels is being presented. Those pixels do happen to resemble a teenager being stabbed, but that’s just not real,” that would not be very thrilling and you would not be very emotionally engaged. Our brains are not great at distinguishing fantasy from reality, and distinguishing benefits in terms of movies, TV, books, entertainment.

However, in terms of goal acquisition, Gabriele Oettingen actually did research on this. When people spent time visualizing themselves thinner and skinnier, the reaction of their brains on the neuroscience level was as if they had already achieved it. The danger there is that that means their brain did not summon the motivation to actually do the work, because their brains felt like we already crossed the finish line; we don’t need to do it. It’s actually very dangerous to simply wish. That’s why her WOOP has four steps, as opposed to merely wishing, because the people who visualize their thinner self actually lost less weight over the course of her study.

Roger Dooley: May be more effective, rather than visualizing your thin attractive self to focus on say a really unattractive photo of you in a Speedo in your current condition. That might provide the motivation, at least to show your brain where you’re really at, instead of fooling your brain.

Eric Barker: Dan Ariely awhile back wrote a piece where he said that a good little hack he had used or recommended to others for controlling eating at Thanksgiving dinner was to wear a sweater that was too tight, and basically acting as a constant reminder of how svelte or not svelte he was. That reminded him, “Oh geez, I’m not in the greatest shape. Oh my God, I can feel my belly expanding,” and that held him back.

The critical thing that he recommends again is context, where if you don’t have the bad food in the house, if you don’t have the bad food nearby … when I interviewed him, he said, “Do you really believe … if I put 20 doughnuts on your desk every day at work for a year, do you think you would be heavier or thinner at the end of that year?” I don’t think any rational person would disagree. It’s like manipulating your context is often the better part of willpower, not having the problem. What’s the best way to avoid a violent encounter or to handle a violent encounter? Don’t be there in the first place. So yeah, I agree.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, Art Markman here at UT in Austin wrote a book called Smart Change, and he pointed out that the most effective way he found to cut down on his ice cream consumption was simply to not have it in the house. Otherwise, try to rely on willpower or other hacks just really didn’t work very well compared to that.

Eric Barker: Oh no, it’s critical, where it’s why rely on willpower? Use your laziness to your advantage. Shawn Achor recommends what he calls the 20 second rule, which he decreases his bad behavior by making anything he knows he shouldn’t be doing take 20 seconds longer, and he increases good behaviors by making anything he should be doing 20 seconds easier. He puts the TV remote further from the couch so he needs to get up and walk across the room. He puts the guitar closer to the couch because he’d like to be practicing his guitar more often. That sounds ridiculously simple. He goes to sleep with his gym clothes and his sneakers next to the bed. Just making those things simpler is surprisingly powerful.

Roger Dooley: You know, I know that Google did some experimentation where … of course, they have snacks everywhere, and needless to say, infinite free snacks, people are going to tend to over consume them, and particularly those things that our brains really like, like maybe chocolate candies and so on. But they were able to shift consumption simply by moving some stuff farther away or putting it in a closed bowl rather than an open glass bowl where it was really easy to access, so all good hacks.

I want to cover one last topic, Eric, and that is luck. I think that probably people who consider themselves rational just dismiss luck and say, “Well, luck is nothing. It’s a probability or whatever, but it’s random.” Then there’s probably another group of people who rely on luck in sort of a magical thinking process, but there’s actually some science behind the way people deal with luck, right?

Eric Barker: Yeah, obviously my whole book is based on the science of things, so when I say luck, I don’t mean luck as in magic or magical thinking. However, I don’t think anybody disputes if they were to stay at home, lock the door, and have food delivered and just not leave the house, how many lucky things, random positive events are going to happen to you? Well, not very many. You’re simply not being exposed to things. So in terms of positive, serendipitous moments, some people have lots of random good things happen to them, some people have fewer. There are ways you can engineer that.

It was Richard Wiseman in the UK who did this research, and he found that there are a number of behaviors that are strongly correlated with more of those positive serendipitous things happening, one which was extraversion. I mean, if you’re dealing with more people, if you’re talking to more people, then there’s more opportunities that will come your way, as opposed to you’re a monk taking a vow of silence, I don’t think you’re going to be exposed to a lot of new interesting opportunity.

Openness to experience, just being interested in trying new things, giving things a shot, really makes a big difference. It’s that issue of you can engineer things and such, so I would say that the science of luck is more analogous to card counting, where you can’t guarantee that you’re going to win any particular hand, but if you do certain behaviors like getting out there, trying new things, talking to people, taking an optimistic attitude, you will increase the odds over a period of time that more positive things will happen to you.

Roger Dooley: I’m curious, Eric, since you wrote this book and been actually writing about these topics for years and years, are you good at following your own advice? Have you found some things you’ve been able to implement into your life that really worked, and others that despite your best efforts didn’t go so well?

Eric Barker: I mean, absolutely, and I initially started all of this because I wanted to improve. No, I can’t possibly follow everything that I recommend, and different people have different reactions, but certainly there have been a number of things, like building good habits is something that I’ve assiduously dedicated more time to, because much like we were talking about the power of context, in terms of building habit, once something’s a habit, willpower isn’t as much of an issue. So much of us want magic bullets, but the truth is that a lot of the best hacks are some of the simplest things, like getting more exercise, getting more sleep, meditation. There’s a handful of very simple things that have very powerful effects. No, I’ve gone out of my way to use a lot … sadly, not all … but a lot of the things I’ve read.

Roger Dooley: Let me remind our audience that we’re speaking with Eric Barker, author of the new book Barking Up the Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success is Mostly Wrong. Eric, how can our listeners find you and your content online?

Eric Barker: The URL to my blog is actually in Japanese so it’s a little hard to both pronounce and spell, so the best thing to do is either to google my name Eric Barker or Barking Up the Wrong Tree. They’ll be able to find my blog. The best way to stay up to date is to sign up for my mailing list, but that’s where people can best find me online.

Roger Dooley: Great, and we will link to the actual website and to any other resources we talked about during our conversation on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast, and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there as well. Eric, I know our listeners will really enjoy your book. Thanks for being on the show.

Eric Barker: I really appreciate it, Roger. Thank you very much.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.