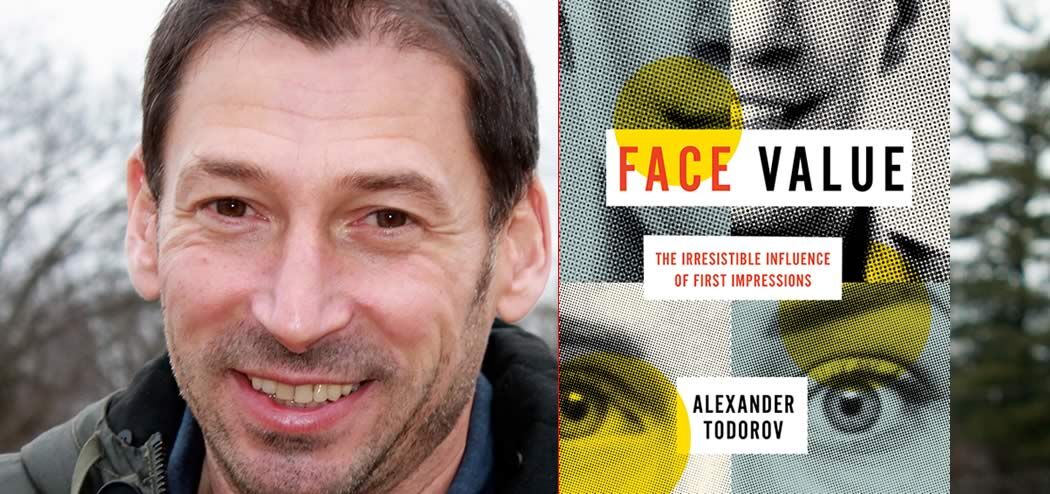

First impressions are formed in milliseconds, are long lasting, and are incredibly important. Knowing nothing about candidates other than their photos, subjects were 70% accurate in predicting the outcome of actual elections. Our guest on this episode, Alexander Todorov, describes this research and shares other insights about first impressions. His new book Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions collects his research and that of other scientists on how facial features, expressions, and other factors can influence people’s judgments and actions.

Alex is a professor of psychology at Princeton University and a widely known researcher in the science of first impressions. He is also affiliated with the Princeton Neuroscience Institute and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. His research has been covered by the New York Times, the Guardian, the New Yorker, Scientific American, PBS and NPR.

What do people assume about you from your photo? Here's the science of first impressions. Share on XAlex’s research gives us some valuable insights into how we are seen by other people. He also shares some tips on how to match your look with the image you want to portray and the importance of a smile.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are still feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Whether or not first impressions are accurate depictions of character.

- How people’s assumptions change based on how much time they have to view an image.

- How Alex’s lab creates renders faces that display a specific characteristic – e.g. trustworthiness – that most people tend to agree on.

- Why viewers’ impressions of others change when they have more information about the person.

- How body language, expressions, hair, and clothing can dramatically change how people make assumptions about you.

- Why it’s important to know your objective and what you’re trying to communicate when you are choosing an image to represent yourself.

Key Resources for Alexander Todorov and Face Value:

- Connect with Alexander Todorov: Website | Bio

- Amazon: Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions by Alexander Todorov

- Kindle: Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions

- Blog: Want To Be More Attractive? Science Says Have A Drink

- Blog: Top 10 Profile Photo And PortraitHacks Based On Science

- Article: First Impressions: Incredibly Quick To Form, Slow To Change

- Podcast: Top 10 Science Based Headshot Hacks on The Brainfluence Podcast

- Francis Galton

- Photofeeler

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week is going to cover a topic that’s incredibly important to every one of us.

Alexander Todorov is a professor of psychology at Princeton University and an expert in social neuroscience. He’s affiliated with the Princeton Neuroscience Institute and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Of most important interest today is that Alex is an expert in the science of first impressions. His work in that area has been featured in The New York Times, The Guardian, Scientific American, and of course, my Neuro Marketing blog. His new book is Face Value: The Irresistible Influence of First Impressions.

Welcome to the show, Alex. It’s a real pleasure to have someone whose work I’ve referenced in the past join us here.

Alexander Todorov: Hi, Roger. Thank you for having me.

Roger: So Alex I’m sure that every one of our listeners agrees that first impressions are important. Business books have drummed that into us for years. You only get one chance to make a good first impression; you should dress for success, smile, look people in the eye; The list goes on and on. But I’d guess that not everyone knows how powerful first impressions and appearance are, and they can influence our judgment in areas like making political decisions, hiring employees and so on. What are some of the things that you found in your years of research that most surprised you or maybe even distressed you?

Alexander Todorov: Certainly yeah, absolutely right about the importance of first impressions. In fact, the very first studies that we conducted in my lab, this was more than 10 years ago, was trying to predict the outcomes of important political elections; in this particular case for the US Senate, from snap judgements of pictures of politicians. And, surprisingly, we were able to predict about 70% of the election outcomes just based on judgements of people who didn’t know the politicians, didn’t recognize the politicians. And, this study’s actually made me really interested in trying to find out and to understand what is behind first impressions.

Roger: Yeah, so the fact that there was a 70% accuracy in prediction of … presumably means that obviously people’s political judgements are influenced by a variety of factors, what the candidates say and do, but clearly the effect that total strangers could predict the outcomes, indicates that many of the votes are probably biased by the first impression right?

Alexander: That’s right. In fact, it was a very interesting and surprising finding, and the first scientists who were really interested in following it up were not surprisingly, political scientists. And subsequent work has shown that the voters were really influenced by appearance, and those who know very little about politics. So, in the language of psychology, they’re relying on shortcuts and heuristics because it is easy. For unknowledgeable voters, and we’re talking about people for example, who cannot name the vice president. This is people who know next to nothing, but nevertheless they vote. And, this is exactly the people who are influenced by appearance; and in very close elections, these are the people who can overturn an election.

Roger: Right, and of course in the United States it seems in recent years most of our elections have been pretty close, decided by just a few percent of the voters, at least at the presidential level. So, yeah, that’s fascinating. Is there … I mean obviously people make these snap judgements and we seem to be programed to make very quick judgements, is there an evolutionary advantage for that? In other words, did evolution select for these first impression judgements? I guess it could be useful if you’re selecting a mate, or trying to decide very quickly whether you should trust a stranger.

Alexander Todorov: Yeah, it is a very, very important question. And, I have a whole chapter in my book on the evolutionary arguments about the importance of first impressions. It very much depends on what you think stands behind these first impressions. If you think about first impressions as giving you information about what is happening here and now in the situation, information about the mental and the emotional state of the others; there’s a very good evolutionary argument to be made.

On the other hand, if you think about first impressions that they give you information about the character of the others, there’s very little of actually good value for this argument. In fact, I write extensively why first impressions are not accurate when it comes to reading the character of people, but they could be accurate in the situation here and now. Just to give you kind of a perspective on the evolutionary argument, if you think about human evolution, let’s compress it within 24 hours. Well, most of the time, except for the last five minutes of this 24 hours, we have essentially lived in small extended families. Where you don’t need to rely on appearance to know what others are like, because you have a lot of first-hand information, you have second hand information; and all of this changes in the last ten, fifteen thousand years where have suddenly modern states, meaning you have to live with thousands of strangers. Then it’s impossible to know them because you cannot possibly have knowledge about every single individual.

This is where this whole idea of physiognomy, the pseudo-science of creating character from faces appears, and it becomes extremely popular in moments of human history when you have a huge migration. So, the peak of popularity of physiognomy is the 19th century, where you have the biggest industrial migration. Suddenly you live with thousands of strangers and it’s a little bit … it’s scary. It kind of helps to think that you can control your environment, that you are able to size up people just by their appearance.

Roger: Yeah, it’s kind of interesting because, I know that many of our listeners are familiar with phrenology, the other pseudo-science of sort of feeling people’s skulls for bumps and ridges and little dents and whatnot, and then making judgements about their character based on that, but the science of reading faces kind of evolved in parallel with that, did it? Or the pseudo-science I guess, in those early days at least.

Alexander: They did, and they were actually tightly connected, although the phrenologists denied any connections to physiognomy, but probably the most famous physigonomist was Johann Kaspar Lavater, who wrote this four volume work at the end of the 18th century, which was phenomenally popular in Europe. In his book he has cages of this kind of cranial measurement, which preceded Gall, the founder of phrenology with a few decades. There are some tight connections between these two disciplines.

Roger: Yeah, well fortunately neither are very popular right now, although perhaps your book will bring back a more scientific approach to it. So Alex, these early face readers were wrong about predicting competence and personality, but they were onto one thing that was real; people tend to make fairly consistent judgment of faces, right?

Alexander Todorov: Absolutely. This is absolutely right. In fact, yes, physiognomists were wrong about quite a few things, but they were right about others and namely they all had the right intuition that we form impressions and we form these very quickly, they’re fairly effortless and they’re immediate, they feel like perception. And in a sense, this is what provides their legitimacy. They have legitimacy, they feel real.

We’ve conducted many studies where we can present faces for extremely brief amount of time, you can flash a face on a computer screen for less than one tenth of a second, and this provides sufficient information for people to form judgements; so this is surprising finding number one. Surprising finding number to is that there is a fairly good agreement among different people. It’s interesting because psychologists have discovered this like 100 years ago that people agree in their first impressions. But it wasn’t paid enough attention. And, a lot of the work that I’ve conducted in the last ten years in my life, has been trying to figure out … well, what is it behind these impressions? What is it that people agree on when they decide that the face looks trustworthy, or competent, or dominant, and so on and so on.

Roger: I guess the important thing to emphasize, again, is even that even though people agree on these, they’re not right. I think that the early face scientists predicted that Warren Harding would be a great president because he looked like a great president, and in general people would agree that he did have a very presidential look, even though history would say that he was probably one of the least competent presidents of our entire history.

Alexander Todorov: That’s exactly right. In surveys of American historians, he’s rated as the worst president in the history of the United States. And, actually you can find books from the 1920’s when he was president, physiognomy books, which were very popular, which show how his chin demonstrates his presidential greatness. Alas, history shows otherwise.

Roger: Right. Maybe we should all get chin implants if we want to look more presidential. Today we take morphing software for granted, where you could take my photo and Donald Trump’s photo and come up with some really weird composite face, no doubt, but … I was surprised to read in your book that they were experimenting with composite photos well over 100 years ago. What was the point then?

Alexander Todorov: That’s exactly right. This is actually another interesting connection between physiognomy and eugenics. The science of selective breeding. And, the person who actually … I would say the father of modern morphing methods, the way … well, not the way we know them today, today everything is digital. But, Francis Galton who was a polymath and a cousin of Charles Darwin, he came up with an invention that he called composite photography. The composite photography was essentially super-imposing negatives of different photographs to create an average image.

In fact, his first project was to find the face of the criminal. So, he will take faces of prisoners and try to … He was superimposing them and try to find out what the typical criminal looked like. But he actually had even great ambitious for composite photography. Galton, he was an amazing scientist and probably would have been celebrated as the greatest scientist of 19th century. One of the greatest if it were not for his preoccupation with heuretics and eugenics.

He invented correlation and regression, he had invention in geography, materiology; he was quite phenomenal. But also, kind of an odd character, really obsessed with eugenics. His understanding of how to translate Darwin’s ideas for the betterment of the humanity, though not with the most ideal tools. In fact, the first eugenics society was the race hygiene society in Germany; this is 1905 and he was the honorary president. So for him, the composite photography was the ideal tool of eugenics. The way he saw it was with composite photography, you can find out what’s the ideal English type? And if you know what the ideal English type looks like, well, you should encourage breeding or mating only of those who look like the ideal British type. And those who are very atypical or very different from what the ideal British should look like, they shouldn’t be allowed to breed. That was essentially eugenics, and this was the tool for eugenics.

There were a lots of interesting parallels with these kinds of theories back in the past.

Roger: So his work with photographs kind of pre-figured your own work with digital composites and really the vast amount of manipulation that you can do now using these tools, even … you know, not using actual faces, creating faces and doing all sorts of things. I wish we had visuals here on this audio podcast. One of your experiments was to create composite of images that showed introversion and extroversion and you said you created these by brute force. What do you mean by that?

Alexander Todorov: Well, I mean by brute and difficult force. So, this is what we call it in psychology, data-driven methods, which are not influenced by our theoretical hunches. So as I said, one of the main directions of research for me in the last 10 years or so has been trying to figure out what is the consensus behind first impression; what is it that people agree on? And to do this, we actually built mathematical models that visualize this consensus. In this particular case, we did this for introversion, extroversion, with competence, trustworthiness, dominance; we can do it for any impression in which there’s some agreement. The way we do it is we simply work with a statistical model that represents faces. The important thing is that I can generate as many synthetic faces as I want, and each face is kind of like a set of numbers. It’s completely determined in this mathematical space, which was derived from laser scanning and three dimensions of real faces. Now, once I have this, all I need to do is generate a samples of faces and ask naïve participants to form impressions. Like trustworthiness, dominance, and so on.

And now because I know what the faces look like, I can build a mathematical model that captures the cues that people are using when they form a specific impressions. And in this way, we can actually visualize, oh, this is the stereotype of introversion/extroversion, this is the stereotype of trustworthiness. In fact, we can exaggerate the differences along any dimension. You can think of this model it’s like an amplifier, where I’m amplifying the signal of these kinds of impressions. The book is very, very richly illustrated, because it is difficult to verbally describe all of the changes that we capture. All of the changes in facial features that we capture when people form various impressions.

Roger: We’ll try and include, maybe on the show notes page, just one or two illustrations. And, of course people can grab the book itself and see them all. Yeah, this really is sort of a visual topic. First of all, you mentioned that we form an impression in less than a 10th of a second. How stable is that? In other words, say I’ve got a much longer amount of time to study a photograph; how much does that impression change?

Alexander Todorov: Well if it’s just about the amount of time, impressions don’t change much. In the very first study that we did, we presented faces for 100 milliseconds, 500 millisecond, and full second. Subsequent studies we actually ended up using even shorter presentations. But the general finding is that essentially you don’t need more than 160 milliseconds to form coherent impressions. And, if you keep increasing the time exposure, the only thing that changes is your confidence. So, people become more confident in the impressions. That doesn’t mean that you cannot change your impression. If you provide information about the person, people always change their minds. So you can show a person a face of a handsome man and then say well they’re actually a serial murderer. Well, naturally people will change their impressions. But just based on visual appearance, the time doesn’t mean anything.

Another thing that I have to say is that these impressions are very much image dependent. So you can have different images of the same person, and they can lead to completely different impressions. This is one of the reasons why you believe … The reasons actually, one of the reasons you believe first impressions lead to something is, our experience with familiar faces. When you look at familiar faces, it doesn’t matter whether the person is smiling or not smiling, whether they’re shaved or unshaved, whether they have long hair or short hair, you immediately recognize them. And this recognition comes with your knowledge and feelings toward the person. We kind of tend to assume that this is the case every time you look at an image. But when you look at images of strangers, your impressions are extremely determined by the specific image you’re looking at. If you’re looking at a very different image of the same person, you will end up with a very different impression.

Roger: Right, and I think that’s the important thing that our listeners need to get. Even though people make snap judgements about faces and you can say certain facial characteristics make you seem more or less trustworthy and so on, that there is a huge amount of influence that comes from the other information in the photo, which could be whether the person is smiling, whether they’re looking directly at the camera, or to the side and so on. I guess that’s correct right? There’s all …People process all this information, so the same person could look trustworthy in one photo and maybe not so trustworthy in another.

Alexander Todorov: Exactly. Yeah, we have done studies on this and the other studies from other groups and this is exactly right. I mean, your eye gaze, your emotional expressions are very important. People have done studies with images of people who are sleep deprived or not. Well guess what, if somebody hasn’t slept for 30 hours, you take their picture under standardized conditions where they’re rested and they had a good night of sleep, or after they’ve been sleep deprived; well if you show these images to two different groups of people, the people who see the sleep deprived image, they think, “well this person is not very smart, they also seem somewhat depressed”, and that’s because you can tell sleep deprivation. You know, if you just put the images next to each other, and again I have an illustration in the book, it’s obvious. The sleep deprived person, the skin is paler, you can have these droopy eyes, and all of these things make the person look like they’re not very smart or not as smart as when you have the good image. And they’re also somewhat depressed.

And again, to get back to the accuracy of first impressions, that could be true in the immediate situations. Because if you’re sleep deprived, you’re not going to do well performing some kind of a cognitive task right? Like solving a complicated problem. But this is not an indication what the person is like in general, it’s an indication of their temporary state at this particular moment of time.

Roger: But it might still be accurate. What about hair? Most of your tests involve sort of oval shaped faces that don’t have hair or like clothing, shirt and tie or something else associated with them that would bias the viewer, but in the real world of course, that’s how we experience other people.

Alexander Todorov: Absolutely, and all of this extremely important actually. I mean, the hair can change very much your impression, and we have some illustrations in the book where you can get an ambiguously racial face that, kind of can look Hispanic or African American, and depending on the hairstyle people can see it as a Hispanic face or as an African American face. You can also make the … depending on the hair, the face to look more competent or less competent and so on. And the hairstyle is something that we can manipulate easy.

Clothing, extremely important. We actually have a series of new studies, and we’re working on this new manuscript that, just like with information from faces, you can have the same face but you have different kinds of clothing, more wealthier looking clothing, and less wealthier looking clothing, and just like in impressions from facial appearance, people make very rapid judgements after very brief presentation of these images. And they perceive the same person when they’re dressed up in a kind of wealthier looking clothing as more competent. So these are the cues that we very rapidly integrate. We have also some interesting studies … gestures, body language is also extremely important. I write in the last chapter about a series of studies we conducted a few years ago where you take extreme emotional expressions, so people who are experiencing pain or pleasure, or you know … we used the faces of tennis players after winning or losing a point. Turns out, if you just show the faces to people, they’re completely at chance, they don’t know whether the experience is negative or positive. Everything looks pretty negative when it’s extreme.

But just show them the bodies, people are fairly good at telling, well the person just won a point or lost a point. And at the same time what’s happening here is interesting because people think that they get the information from the face when they look at the intact image. But we know experimentally that there’s nothing in the face that gives them the right information, but our brain disambiguates very rapidly what’s going on. Our natural focus of attention is the face, and we think the face provides a large amount of information, but in real world, all of this information come from the face but many other cues, and these cues, clothing, expectations, what just happened a minute ago, help us disambiguate what we see in the face. So it always feels like we get lots of information from the face, but there are multiple sources of information.

Roger: Yeah, I feel … You’re probably familiar with the photo-feeler app that lets you rate photos or have people rate your photos for competence and likability I think are the primary metrics there. And, they include when you’re rating somebody else’s photo, a job title, which in one way makes sense because, it gives context for the rating. But at the same time, I really find that my rating process is probably influenced by that. So, if it’s a young guy in a t-shirt, and it says intern, I’m liable to rate that person as less competent than if it says founder and entrepreneur; Even though they might actually be the same age, same look and everything, but that … the context there, even just in the title is making … giving me information that I use when I make my rating.

Alexander Todorov: Absolutely, I totally agree. Because, you immediately … The context creates a set of expectations. I mean, if you are CEO or you are creating new businesses, and you’re in a t-shirt, well you can do it because you’re so wealthy and you can do anything you want. But it looks differently on intern, absolutely.

Roger: Right. Yeah exactly, the intern needs to dress like the CEO, but the CEO can get away with dressing like the intern.

Alexander Todorov: Yeah.

Roger: Yeah. So, most of our listeners are involved in business of some type, and all of us have to put photos out there for social media or for other similar purposes where other people are going to be making those less than a 10th of a second first impression judgements of us. What are some of the … What characteristics do you think that they should be optimizing for? In other words, credibility or dominance, or trustworthiness or likability. What are some of your top tips for improving that look?

Alexander Todorov: It very much depends on again, the specific context. What is it that you’re trying to communicate … Whatever you’re trying to communicate should fit your objective. Again, whatever the specific occupation is. For example, dominance seems to be very important for the military, and in fact there’s some work suggesting that people in the military have more dominant faces. They have better career outcomes, but that wouldn’t necessarily be the best … that might not be a characteristic that matter in other professions. Perhaps in sales professions, in sales maybe you’re looking for extroversion. So you need to have a sense of, what are the desired qualities? What are the desired attributes in this particular situation or context, and then ideally your picture should present you in the most favorable light in terms of these qualities. But ultimately, the best thing is to have qualifications that in fact correspond to what you’re trying to achieve. And if you can post these qualifications, this is much better than any image, but you’re right that the fact of the matter is people will make too much out of the images so we need to be careful about the images that we are posting of ourselves.

Roger: It’s … One of the … I don’t think it was your lab that did this but, there have been quite a few research projects involving alcohol and there was one that showed that if your photo showed you with even a glass of wine in the picture, that you were perceived as being less intelligent, perhaps some sort of subtle reference to cognitive impairment you know? That well, this person’s been drinking wine, they’re probably not as sharp as a person who hasn’t. And then another one that I found fascinating, was that people who has one drink before their photo was taken were actually viewed as more attractive, but then two or more drinks reduced that because then you probably were seeing almost that sort of same thing that the sleep deprived people you talked about. Where, they actually were cognitively impaired at the time the photo was taken.

Alexander Todorov: Yeah, this is very interesting. I’m not familiar with the studies, but it makes sense.

Roger: Yeah, it’s great stuff. I’ll slide you a link later, but it’s you know, it’s fascinating research. So, what you’re really seeing is that we individually need to determine what impression we want to make and that is somewhat position dependent. A CEO or a person who perhaps has a whole lot of people surrounding him that’s going to be selectively meeting with people and doesn’t have to be outgoing and dominance might be a good characteristic there. But, on the other hand somebody who’s in sales might want to appear likable, might want to appear extroverted because they’re constantly going to be interfacing with new people. And, if you don’t look like somebody who’s likable, they’re not going to return your phone call.

Alexander: That’s right, yeah.

Roger: Right, and I should add too that there are lots of photos in the book that show what some of these characteristics are, and your facial expression … just because you have a specific set of features that you were born with or you grew into, you can alter those by your expression. What about smiling? What does smiling say about people Alex?

Alexander: Smiling is very important and it’s one of the main inputs to impressions of trustworthiness. And trustworthiness is one of the most important impressions. So when we build these models … and it’s kind of interesting because it’s a data driven model so we don’t know what will come out at the end. It’s not like we say … it’s a very different approach than let’s manipulate whether people are smiling or not and see how they would be evaluated. In fact, we just randomly generate faces and then people make judgements. And then based on their judgements, we can extract the cues that shaped the judgements. And in fact, when you look at these models of trustworthiness in particular, as the face becomes more trustworthy looking, it becomes to look happy. And at some point if we keep increasing the magnitude in the model of this signal, the faces no longer look emotionally neutral, they look happy.

And on the other hand, as the face becomes more untrustworthy looking it kind of looks disgruntled and angry. So emotional expressions and subtle emotional expressions, they don’t need to be fairly explicit, are very important when we form impressions.

Roger: So do you have any advice for people? Assuming they’re in a … somewhat pf a contact type of business position, whether that’s sales or just perhaps interacting with people in other companies, a small smile, a bigger smile, show teeth, open mouth?

Alexander Todorov: Again, it’s hard to tell. You know, it’s very much will depend on the specifics. I mean, in this particular case, in our models we’re just modeling what comes out in this … out of these impressions, and …I mean, if you keep exaggerating at some point the face becomes like caricatures, right? And a happy face might not look very competent or stable. So there’s always limits to how much you can exaggerate your own expressions.

Roger: Well yeah you know, I think you’re right Alex; because I know I’ve seen some social media photos where people look like they were just told the funniest joke they’d ever heard in their life where their mouth is totally wide open and they’re laughing … appear to be laughing like crazy and, obviously I’m sure a photo like that would score pretty high for extroversion, but not … at the same time it might not necessarily inspire a feeling of competence.

Alexander Todorov: That’s right, yeah. So it’s really, in that sense, the applications like photo filler, seem to be useful because it’s important … You need to have some kind of a criteria on what are the perceptions of the image, and for this you need other people who are unfamiliar with you. And often we might not be the best judges of which is the best image if I was sales?

Roger: For sure, it’s pretty hard to judge your own image.

So Alex, you focus a lot on politics in your own research, and in the book. I have to ask you about the last US presidential election. Did you call that one correctly before it happened, or what were your thoughts on that in the lead up to the election?

Alexander Todorov: Well we actually never try to predict specific races because there’s just incredible amount of uncertainty involved. And, most who don’t look into presidential elections because everybody is familiar with the candidates. Unless you go to some country in the world where people have never seen the candidates, and that would have been very difficult for the last election in particular. So what we usually will do is, like, we’ll look at say 100 senate races and see what is the percentage of the races that we can predict? So actually I didn’t try to predict the last election.

Roger: Yeah, just looking at say, Trump photos; I get a lot of dominance out of those photos. He just sort of has that scowl on his face all the time that seems to suggest dominance.

Alexander Todorov: Yeah, yeah. I mean, again it was a very interesting collection because it was highly …people have so much knowledge and the opinions was so polarized …

Roger: Right, but knowledge of all kinds, accurate knowledge, inaccurate knowledge, but you’re right …

Alexander Todorov: That’s a whole other story, yeah.

Roger: Presumably that’s … There’s just so much information out there that the first impression effect is reduced somewhat. And I think too, in this case, with two candidates who are very dissimilar in appearance, that might also make that kind of evaluation more difficult. So, let me ask you one last question Alex; You probably had a publicity headshot for your book launch, did you optimize for any attributes on that?

Alexander Todorov: This is actually kind of funny because, given my research I should have taken this really seriously, and in fact I left it until the last weekend and my wife took a few dozen shots of me, and then eventually we narrowed it down to two. But, I should have worked more seriously on this.

Roger: It’s always the Cobbler’s kids who go without shoes right?

So, great. Well let me remind our listeners that we’re speaking with Alexander Todorov, one of the world’s top researchers in the science of first impressions, and author of the new book, “Face Value: The irresistible influence of first impressions.”

Alex, how can people find you and your content online?

Alexander Todorov: My lab webpage – it’s “tlab”, from Todorov, tlab at Princeton dot edu. And we post all of our publications there, there’s information about the book, there’s information about media coverage, so everything is there. Or you can just Google Todorov Princeton University, you’ll get to the lab webpage. But it’s tlab.princeton.edu.

Roger: Great, well as always we will link to those places and any of the resources we mentioned in our conversation on the show notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast. And I’ll link to a few of the previous articles that we published and most fairly recent podcast about optimizing profile photos and we’ll have a text version of our conversation there too.

Alex, thank for being on the show.

Alexander Todorov: Thank you for having me Roger.

Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.