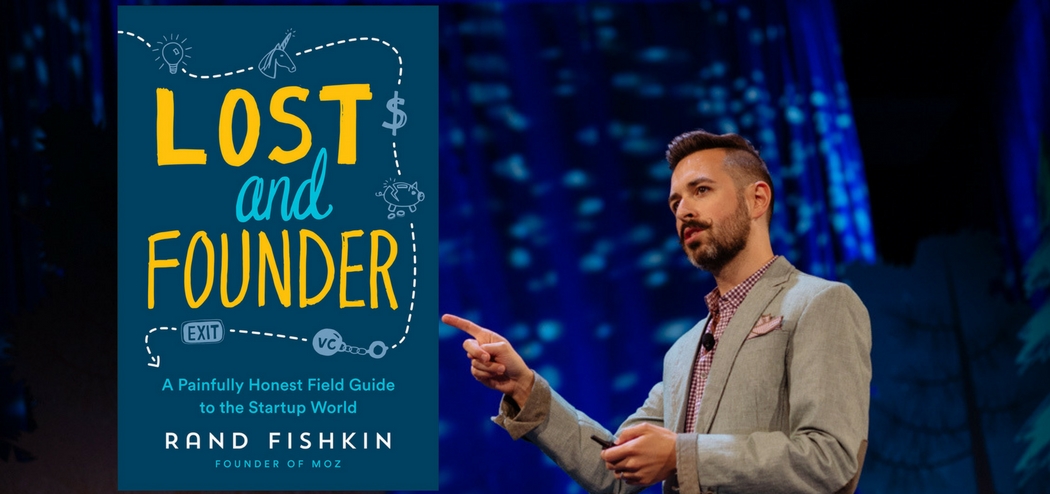

Any good marketer should try to keep up with Google’s ever-changing metrics, and Rand Fishkin is one of the best resources for doing so. Rand is the founder of SparkToro, and was previously cofounder of Moz and Inbound.org. He’s dedicated his professional life to helping people do better marketing through the Whiteboard Friday video series and his blog. He also shares business advice—as well as his personal story—in his new book, Lost and Founder: A Painfully Honest Field Guide to the Startup World.

In this episode, Rand shares the stories behind his entrepreneurial adventures and misadventures, as well as the major lessons he learned along the way. Listen in to hear what Rand says every entrepreneur must keep in mind when looking into funding, timely SEO advice for businesses, and more.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- The common misconception about venture-backed entrepreneurs.

- What every entrepreneur should keep in mind when looking into funding.

- Unexpected inflection points that changed Moz’s direction.

- The surprising truth about the common markers for success in the entrepreneurial world.

- Which kind of growth hacks worked well for Moz.

- The powerful lesson Rand learned about transparency.

- Why it’s not always good to reduce friction for people to sign up for your list.

- Specific things that make “great content” effective.

- The top few things businesses should concentrate on to get more organic traffic.

Key Resources for Rand Fishkin:

-

- Connect with Rand Fishkin: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

- www.SparkToro.com/book

- Amazon: Lost and Founder

- Kindle: Lost and Founder

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. My first series introduction at digital market was in the SEO, that is search engine optimization space. Back in the late 1990s, a friend needed help getting traffic to a special eCommerce site and so I did some research, started changing things, in short order, quadrupled traffic. That was in the days of AltaVista and Excite and then the early part of the Google era.

This success led to adding additional SEO services to my company’s portfolio. I had the opportunity to work with firms, ranging from fortune 500 size down to really small entrepreneurial firms. Shifted away from SEO a long time ago, but like any good marketer, I try to keep up with the basics and understand how Google is changing its emphasis. One of my go-to resources for staying in touch with Google’s changes, has been my friend, Rand Fishkin.

Rand is the found of SparkToro, but you may know him better as the co-founder of Moz and inbound.org. He’s helped me and many other marketers with his Whiteboard Friday video series and his blog. Rand has a new book, Lost and Founder, a painfully honest field guide to the startup world. We’re going to talk about his entrepreneurial adventures and misadventures and before we wrap of the show, get some timely SEO advice. Rand, welcome to the show.

Rand Fishkin: Thank you for having me, Roger, really looking forward to it.

Roger Dooley: Rand, we’re recording this just as you are going through a major business transition. I know a little bit about it, but why don’t you explain what’s going on in your life these days.

Rand Fishkin: Oh, sure, sure. I’m what? Two weeks, two and a half weeks into setting up a new company, SparkToro, after my departure from Moz Company that I founded and was working at for 17 years, so essentially, my whole adult life. I dropped out of college to co-found Moz with my mom back in 2001. So, this is all new territory for me, setting up all the legal, and accounting, and taxes, and well, you know.

Roger Dooley: Yeah.

Rand Fishkin: All the things that a new business needs in the United States. Yeah, that’s been an interesting adventure. I think created a lot of empathy for small business owners. You know, trying to do a lot of other things, trying to get some product going, get a little bit of marketing going, get some people to know what SparkToro is and what we’re trying to achieve, but of course, we’re probably a good six to nine months away from having a product. Yeah, so it’s been…

Roger Dooley: It’s got to be an emotional thing to leave a company that’s been such a huge part of your life.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, no. Absolutely. It is. I think it’s tough to have perspective so soon after that, but I suspect in the years ahead, I’ll be able to reflect on it with a lot more candor and perspective.

Roger Dooley: I haven’t been through the exact same situation, Rand, but I’ve been in some kind of similar situations and there really is an immediate effect, but over time, your perspective changes. That change can vary, but at least you can distance yourself a little bit. We’ll look forward, maybe too, now reading more on your blog.

Rand Fishkin: Sure.

Roger Dooley: As your feelings about that situation evolve and you want to share your perspective. Rand, I read Lost and Founder and I like the fact that it was part business advice book, but also a very personal story. Now, you had to grow and change a lot, personally, as you said. This was sort of your first gig after leaving your education. You went from basically being a website designer for a tiny services firm to ending up running, what became a $45-million company in the software business too, not a service business.

One of the early takeaways is that success as an entrepreneur rarely follows a predictable linear path. What were a few of the unexpected inflection points that changed Moz’s direction?

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. I mean, there a big number. I covered a few in the book. Obviously, the transition from services to product, to software, was a big one. I think that really changed the way we did everything. As a services business, you are essentially, serving a very small number of people every week or every month. For us, it was less than a dozen, at any given time. As a product business, I mean, Moz, you know, when I left was serving 36,000 paying customers, right? So, incredibly different type of work that you’re doing, type of support you build in.

I think another big inflection point for us was taking investment dollars, right? We did that at the end of 2007. At that point, something big shifts. I think there’s not a terrific understanding of this, but let’s say Roger, you and I build a consulting firm or let’s build a software company, right? We build a software company, it’s doing $45-million a year in revenue and spitting off maybe $5 to $10-million dollars in profit and growing 10% year over year. So, next year, we’ll do $50. We’d feel pretty good about that, I think.

Roger Dooley: Oh, absolutely.

Rand Fishkin: Maybe? Yeah. Not too shabby. Now, let’s make one more assumption, that we’ve raised venture capital. Even a $1-million, just one time from an institutional investor. That company is now considered on the failing lines, right? Not a complete failure but nothing close to achieving what is the desired outcome or the intended outcome. That is because the model of venture is to raise money from limited partners, right? These large institutional funds. A lot of them are pension funds or university endowments, or these kinds of things. They are looking to beat the market’s returns.

They’re trying to find a small handful of companies that are going to ten to 50 X their month and to do that, growth is the only thing that matters. So, losing, you know, if our business was not profitable and was losing $10 or $20-million a year, that’s no problem. I mean, Uber’s losing what? $300-million a year? Maybe more than that.

Roger Dooley: At least, probably. Yeah.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. That is not the concern. The concern is the growth rate and they would look at 11% growth or 12% growth year over year and they would say, “You are letting us down.” This model’s not working.

Roger Dooley: Well, yeah. In effect, you’re throwing off a few million in profit, even if you can return a portion of that as dividends, wouldn’t really move the needle on their overall investment, whereas, individual owners, if you could take that kind of compensation, that wouldn’t be too shabby.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, you and I sharing $2.5-million a year? We’d feel all right about that.

Roger Dooley: Yeah.

Rand Fishkin: This is another crazy thing, right? I think that a lot of us look at a venture-backed entrepreneur and we see someone who’s raised a bunch of money and whose company is doing north of $30-million a year and we think, that person must be financially well off. When in fact, the reality is, and you know, I wrote about this is the book, right? You read exactly what my salary is. You know what my savings are, right?

Roger Dooley: Very transparent.

Rand Fishkin: Oh, yeah. Thanks. Well, but that was a very important point for me, right? I talked to my wife, Geraldine about this. She’s like, “Do we have to put how much money we have and how much you made in there and all that kind of stuff?” And I feel that so often because money is an uncomfortable topic, because it’s something that we feel awkward about, right? I had a nice salary at the end of Moz, right? You know, top maybe 25% of American earners, right?

I think that because we don’t talk about that because it’s awkward, that conversation can’t happen and thus, a lot of people get confused about what is the reality, right? This is my point, that a business that makes a million dollars a year, might make its owners more financially successful in terms of, you know, dollars returned to them than one that’s doing $50 or $100, right?

Roger Dooley: Right. For sure. You know what?

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, I compare to … oh, sorry.

Roger Dooley: No, go ahead.

Rand Fishkin: I was going to say, I know entrepreneurs, even some folks here in Seattle, right? Who’ve started companies that are now public companies, doing hundreds of millions in revenue, worth a billion dollar plus, and they personally made maybe few hundred thousand dollars from that from starting those companies.

Roger Dooley: Right.

Rand Fishkin: Which is great, that’s a nice amount of money.

Roger Dooley: But, compared to the value generated overall, not very good.

Rand Fishkin: Right. I think the question that we have to ask ourselves is, wait, who is making that money? Who are the people that get the money? And the answer is, the people who already owned capital. Right? Money makes money. Work, hard work doesn’t necessarily make money, especially if you put institutional capital into a business.

Roger Dooley: You know, I think there’s probably even a broader point there for entrepreneurs and that is if you’re bringing anybody else into the business, presumably, perhaps because it brings some capital in, but to be sure that your assumptions about the business are the same as there’s. No business that I’ve been involved in ever had to take venture capital or ever actually, you know? Although, I have been a part of Sand Hill Road Pitches, which is kind of fun. One of those bucket list items that you check off.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. Yeah. Did the chapter resonate for you?

Roger Dooley: Oh, yeah.

Rand Fishkin: We already talk about it, you know, you drive into those parking lots and yeah.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, it was wonderful. Yeah, I really like the idea, I’ll have to talk to the partners about this and we’ll get back to you. In even accepting Angel Funding or whatever, sometimes, I know that I did quite a bit of looking for Angel Funding or just an investor funding for a while. People came in with such radically different ideas. We had one guy who was all about taxes. Like, spent an hour talking about how we were doing taxes and had these six different plans for doing business in a way that would create massive tax deductions and it was like, okay, this persons on a totally different wavelength, if not a different planet than we are.

Ultimately, we did bring in a partner, who was an investor. We had almost the opposite of the conversation you’re talking about because even though at the beginning, of course, everybody has this shared vision of, “Yeah, yeah, you’re doing a great job. We’re just going to come in and be part of that.” The new partner’s idea was that a smaller more profitable business would make sense where the business model that we were pursuing, my original partner and I were pursuing, really required scale to work. We could see the competitive layout and we’d scale it to an eight-figure business, but to be competitive we knew that we had to scale it probably at least another 10 X.

This duality of strategy created a distraction internally because we were sort of simultaneously, pursuing a couple different markets and it ended up not making life in that business pretty difficult. I think that lesson can go in … it can take many forms, Rand.

Rand Fishkin: Sure. Sure.

Roger Dooley: It’s a great, and I think what you describe in the book, of course, is what most entrepreneurs think of as nirvana. You know? Getting big VC investment.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Where man, you’ve got all the money in the world and people love you and your in Techcrunch and all that kind of stuff.

Rand Fishkin: It’s such a celebration.

Roger Dooley: Yeah.

Rand Fishkin: I’m actually … I worry about that a lot. I think that the, what do I want to say here? I want to say that the flags, the markers that we set up for success in the entrepreneurial world, include a subset of things that are negatively correlated with the best possible outcome for the customers, the employees, and the entrepreneurs. Some of those, for sure, come from the mythology around the, you know, Silicon Valley startup culture world, including, “You raised a lot of money.” So, you and I raise a lot of money for our business and what happens? A lot of people reach out and they say, “Roger Rand, so proud of you. Congratulations. We feel awesome about it.” We get a lot of press about it, right? We feel that’s a positive milestone.

When in fact, I think our friends should probably be reaching out and going, “Oh my God, you just took on a huge obligation that took your business from one with a 50% survival rate over the next five years to a 10% survival rate over the next five years. I hope you know what you’re doing.”

Roger Dooley: Right. It’s a great lesson. I think the book is very cautionary, in that respect and not that many people even have the opportunity to take $10-million in VC funding or more, but it’s still very cautionary.

Rand Fishkin: Well, when you feel … yeah, yeah. My intent is partially to be cautionary, right? Partially, to say, “Hey, you better understand this model before you raise.” But also, to say to people who are like me when I was in my mid-twenties and worshiped this idea of being a venture-backed entrepreneur. Right, which seems to me to be the pinnacle and I think for many many entrepreneurs, tons of people that I talk to, right?

You know, my wife and I are small investors in Tech Stars, for example, right? And I talk to a lot of companies there and through a bunch of our other networks, and I hear this, “Well, you know, if we can raise from these people, if we can get this amount.” The focus is off of, if we can serve customers, right? If we can build this amazing thing that will help people, too, if we can get this money.

I think that is probably misplaced goal setting. I want to try and have that conversation with other entrepreneurs to say, “Hey, it may be the case that venture capital is right for your business, in which case, yes, congratulations if you get it and I think that’s wonderful that you’re going down this path.” So few people understand the mechanics of it, even those of us who’ve taken it. I think until we go through the full experience, it’s hard to truly understand the mechanics.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. You know, I mentioned transparency, Rand. That I think has been a core value of yours for a while. I know, you certainly talked about it in the book and previously in your online writings, you’ve talked about transparency. I’d like to get your thoughts on what that’s so important. I’ll preface that with a little comment. Not that long ago we had a guy named, Bob Bethel, on the show. He’s turnaround expert. He’s the guy that the banks go to when their loan is in deep trouble and they’re afraid they’re not going to get paid back.

Basically, he ends up taking over the business to try and fix it to get the bank paid off. Interestingly enough, you would the that the strategy number one would be to say, “Okay, let’s lay off half the people.” But in fact, he says that he has never had to make big cuts like that. Instead, he simply increased transparency. He would begin immediately, after assessing the situation, have an all-hands meeting and explain to everybody exactly the dilemma that the company was in and what had to happen from a cost and profit standpoint to allow the business to survive and their jobs to survive.

And then, mostly left it up to them, not that he wasn’t involved. Supposedly, this has worked more than 70 times for him and has not had one fail yet, where he would typically, buy the business for a dollar. He’d basically take the business over, but assume all the liabilities, would be the bank loan, or what not. It’s worked every time.

Rand Fishkin: Amazing.

Roger Dooley: It sounds so strange to people who are custom to not sharing everything.

Rand Fishkin: Yes.

Roger Dooley: Say, “Oh, my God, if employees knew every word, they leave in droves. We wouldn’t have any people left.”

Rand Fishkin: Right.

Roger Dooley: With that preface, Rand, what is your experience been with transparency?

Rand Fishkin: I wrote about this is two chapters. One at the very start of the book and one at the very end. At the very start, I wrote about transparency as a core value that came personally for me as a reaction to my upbringing, and my early professional experiences, and family experiences around not being transparent, and all the pain that that caused. In the last chapter, I talked about it around the layoffs that Moz did back in 2016 and how incredible I found it that, you know, how frustrated, and angry, and I think reactive, negatively reactive, people were when we did the layoffs, particularly, because we weren’t transparent that they were a possibility, right? That that was something could hit, and we hadn’t been as open about the financials.

And then, the reaction months later, when everybody was on the same page and understood, these are the mechanics of the business. This is what has to change. This is how we have to bring down costs. This is how we’d have to bring up revenue. It was remarkable to see better performance from basically, every single part of the company when we were transparent and when we focused. That’s going to be a powerful lesson for me going forward.

This is something that I’ve always lived by, but being transparent internally and externally, has these awesome powers of getting people on your side. Right? I think that when you put the negative things out there, and you give people a shared mission, and you let them understand the fullness of the situation that they’re in, they make much better decisions than when you said, “Look, just do this because I’m telling you to do this, and I’m your boss and let me worry about the reasons why.”

Roger Dooley: Right. Not only that, they probably make better decisions than you, in many cases, because they’re doing it every day.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: I mean, I think that’s something that probably I’ll have a sort of, long time managers and entrepreneurs is a feeling that, we’re pretty smart and there’s almost nothing that we can’t do if we put our minds to it. That doesn’t necessarily mean that we need to be making every decision and that we’re going to make those decisions better than the people who are in that slot. If you simply empower them to make those decisions and give them the information that they need, overall, the company’s going to work a whole lot better than if you’re trying to do it the way you want to.

Rand Fishkin: Well, and I would say that the other side of that is that if things aren’t working well, you know that you have wrong people in those positions. That is also something that, as a business owner, or CEO, is incredibly powerful, or a manager, right? If you give someone the tools and knowledge to do their work, and the independence to get it done, and they commit to things, and then they don’t get them done, or don’t get them done well, you get to hold them accountable. Whereas, if you’re the one dictating everything and keeping them in the dark, it’s very hard to reverse engineer the causality of why things don’t go well.

Speaker 4: Yep. Shifting gears, Rand. You talk about growth hacking and that’s kind of an abused buzz word these days, but how is growth hacking a part of or not a part of the growth of Moz?

Rand Fishkin: Sure, I mean, just like a lot of companies, a lot of startups, especially, we sought out these short term, you know, I think I like to call them, this one weird trick to save your startup, which I think is the growth hack’s motto. What we found that was that growth hacks that were in service of reducing friction in our existing marketing flywheel, worked really well, right? So, by those, I mean, we have a flywheel, something that’s scaling with decreasing friction. So, each revolution of the flywheel is easier and easier to turn. Each marketing effort that we undergo, is easier than the last one because it’s building on the work of the previous one. For us, we had a big content in SEO engine and that was driving the fast majority of our traffic and our free trails. Many businesses different kinds of flywheels.

But, when we found growth hacks that sort of eased that friction, made that flywheel spin faster, those worked well. When we found ones that were outside of that, these one-time unique, one weird trick to boost your email sign up rate, one weird trick to boost your conversion rate, short-term, right? Or, have these crazy promotional offers, those kinds of things. What we tended to find is that in the very short term, they did have a positive impact. In the long term, they tended to be a net negative on business because a lot of growth hacks don’t do the crucial things that a business should want to do. Which is, they don’t help you serve customers better. They don’t make your product better. They don’t make your marketing engine better. They don’t make your employees happier, right?

They are merely these external, usually, one time, hard to chase, hard to replicate, events that in my experience, follow Andrew Chen’s law of shitty click-through rates. Which is the first time a tactic is exposed to people, it works fairly well and then the future times when you’re exposed to that sort of exploitative tactic, works less and less well. The pop up is a perfect example, right? Worked well in the early days of the internet, now everybody hates it, doesn’t work well.

Roger Dooley: Right. You know, I’m certainly all about reducing friction. That’s one of my mantras for sure. But sometimes, if what you’re doing say, is getting people to sign up for your list or sign up for a trial, if it’s so easy that no thought goes into on their part and they’re unlikely to use or benefit from it, or much less convert later on, then you’re really just doing yourself a disservice because you’re creating all these people who aren’t having a great experience end up opting out anyway.

Rand Fishkin: And then burning your future customer set by exposing them to something they don’t need now or giving them a negative experience.

Roger Dooley: Right and then I had to cancel that.

Rand Fishkin: Awful.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Even in lead generation, I’ve seen that sometimes, I mean, clearly the easier to you make it for somebody to sign to inquire for information, whether it just gives me your email address, verses, fill out these ten form fields. You know, obviously, you’re going to get more inquiries, but if you have a sales department that has to then sort through those and figure out who to follow up on. It ends up being a hopeless task. There’s a whole lot of wasted cost and spinning the wheels there, so that’s a good point.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. No, that’s a great example. We have done some things like that where we reduced friction to sign up for something and then yeah, to your point, the dumb way to do it is to simply send the same message to everyone. The smart way to do is to put those emails into something like a full contact, right? That can give you a tone of information about who that person is. You can go research them online and all their social accounts and that kind of stuff and figure out. Ah-ha. This is a right target, or this is a right target for this product and so you’re essentially saving the person the friction of entering all their information because you can get it all, once they give you their email and then customize the messages to them. And determine if they’re a right target, verses, simply blast everyone with the same promotional offer or whatever it is.

Roger Dooley: Right. Yep. Rand, you mentioned marketing flywheel and maybe you can elaborate just a little bit, I gather that a key element of that is creating great content and, in your case, that people would find either via Google or through Share, or Social Sharing, or whatever. Explain this, sort of, how that flywheel worked in your mind.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. Well, first off, I kind of hate and want us to retire the phrase, great content because I think it’s become so universal, as to be near meaningless. I think that the greatness of the content is not what correlated with it working well, right? There are a bunch of other more specific things like, the empathy that the content showed for the audience. Like, oh this is a thing that you actually really need right now that truly solves a problem for you. Or, the comprehensive accuracy and trustworthiness of the data or information. Or, the uniqueness of the presentation of it, which could fit under the moniker “great”, but I just feel like great is too generic a term.

In terms of flywheels, more broadly, so I want to be totally clear. Moz had one type of flywheel. A content in SEO flywheel. We create content, and we’d amplify that content, and we’d boost our search engine rankings, and our audience reach. That would help us reach more people next time, and boost our domain authority through earning links, and that would help us rack for more and more keywords the next time. This engine kept turning. There are tons of types of engines.

Roger Dooley: Considering your target, were people who were trying to do well in Google.

Rand Fishkin: Sure.

Roger Dooley: Using Google as a traffic source, probably a pretty good strategy.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, yeah. Not bad at all, right? There are lots of different kinds of flywheels, right? I talk in the book a little bit about, you know, there’s a press and PR flywheel. A good example of that would be like Dollar Shave Club, out of Los Angeles. There are flywheels that are based on purely advertising models. There are flywheels that are based on recidivism and referrals. There are flywheels that are based on affiliate models. There are flywheels that are based on almost entirely on email marketing models.

Many many different kinds of ways to build an engine to build a flywheel, but all of those or having a flywheel that scales with decreasing friction, that is the correlation I’ve found with companies that successful long-term at marketing, verses, those that aren’t.

Roger Dooley: I want to get on to the SEO stuff but let me ask you about one last thing that I found fascinating in the book.

Rand Fishkin: Sure.

Roger Dooley: You did a trading places experiment, Rand … entrepreneur or owner. Explain how that worked out. I got to tell you, I haven’t really heard of people doing, but I thought it was brilliant.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it’s one of those late night, in a bar ideas, that you wake up the next morning, you’re like, “Yeah, let’s actually do this thing.” This is Will Reynolds, who’s the founder and at the time, was CEO of Sierra Interactive. I believe he’s now promoted someone else to the CEO role and is in an owner position. He and I basically took a full week and traded professional lives, so he lived at our apartment on Capitol Hill and walked to our office in Seattle and ran Moz for the week. I got permission from my investors to have him make actually decisions and be CEO, not just in title, but for real.

Same thing, I ran Sierra Interactive for a week in Philadelphia. I think we both reflected on the fact that the experience was very powerful, and mind-expanding, and made us both smarter about our own businesses. I guess seeing something from that perspective is just a really … you gain a ton of empathy. We also agreed that the hardest part, by far, is running someone else’s email. Right? Both of us get a lot of email from people internally and externally and replying to emails as Rand in Will’s shoes and Will doing the same, was just hard.

Roger Dooley: Well and even in figuring out what you could just delete or ignore too. I’m sure, like I know though, okay, I can ignore this one, but somebody who is sitting in my seat, may not really know that and would feel obligated to respond in some manner. You know, Rand, one thing for folks who can do an entire week exchange, which is pretty aggressive, but very cool. Something that I learned in my entrepreneurial days, for a while I had a direct marketing business, and we had a fairly advanced direct marketing software, at least for the time.

As a result, we had a chance to interact with other direct marketing and mail order companies, where they would come to our facility to visit to see how the software’s working, or we would visit their facility, or even exchange visits. Like, “Hey, you can come look at us if we can come look at you.” And just in a visit and sometimes of a few hours, you would always learn something different. Even when you think, oh, this company is smaller than we are. They’re not as sophisticated or smart as we are, they were always doing one or two things better than you or say, “Wow, why didn’t we ever think of that?”

It was always very eye-opening. Even if you can’t do a complete swap, even just being sure to interact and visit other places that might be in your space. Even a somewhat different space, but where you might have something in common, I guarantee you’re always going to learn something.

Rand Fishkin: I think you’re absolutely correct. Yeah, in the book I wrote about a bunch of other tactics that we’ve tried, that I’ve tried to live the lives of your customers and I think that’s a … you know, whatever you can do on that front, will have a positive impact.

Roger Dooley: You know, teased about some SEO, at the beginning.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah.

Roger Dooley: What do you think in today’s day and age, where obviously Google’s got way more sophisticated than they used to be. What are today, the top few things to concentrate on for any business how wants to get more organic traffic?

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, I mean, I think that the strategy has shifted slightly because of how Google’s doing things today. One of the big things that’s shifted for sure, is keyword research. At the fundamental level, what you’re trying to do is understand your audience. What are they looking for where if your website company came up and they clicked on you, it would leave to positive things for your business. I think being able to determine that in the past, was really around the relevance or infinities that your audience had with content and with your company’s purpose.

Today, I think you have to add in an additional element, which is, what is Google actually displaying in the search results? I had considered that from two perspectives. One, are they displaying things that suggest that they searchers intent, what someone who is querying that keyword phrase, actually wants that’s different from what you’re hoping to accomplish. A good example of this is if you say, “Hey, I want to rank, you know, we started a new kitchen appliance and we have a new, I don’t know, competitor to the Cuisinart, right? It’s a food processor. We want to rank number one for best food processor.”

Well, guess what? When you search for best good processor in Google lists for media companies and bloggers come up. There’s no individual product that can rank there because Google knows searchers do not want one product. They want a list. They want criteria. They want someone independent and editorial who’s ranking these. You might argue, “Well, some people are truly editorial.” Okay, fine. Google’s trying to figure that out, but maybe they’re not perfect at it. And so, that might not be a space that you can compete in, at least not in the way that you would like to where you just have your own thing.

Roger Dooley: It would be awesome if you could rank for best food processor.

Rand Fishkin: Sure.

Roger Dooley: But the odds of that happening, are slim to none.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah and getting slimmer because Google knows the searchers intent.

Roger Dooley: Ranking is difficult these days because you have competitors, but here, even your competitors aren’t ranking for them. It’s editorial content.

Rand Fishkin: Right. Right, right, exactly. Yes. Precisely. This is not a space where you and your direct competitors can compete, at least not with the type of content that you traditionally think of. Now, if you’re willing to hire someone externally and have them editorially rate on a bunch of criteria and you host that on your site, or host that on a microdomain, microsite, or something like that, maybe. You know, maybe you would have a shot at it that way.

That’s on the search intense side, the other side, I think that’s crucial in the keyword research side, is looking at what features appear in the search results. If there’s four ads above the fold, instead of one, or two, or zero, your click-through rate is going to be considerably lower on the organic results. If there’s map’s results, right, because Google has determined, we think this is a local query. Well, now you’re not going to rank, except in maybe one geography where your business actually is, unless you have many locations, right?

You should consider biasing your efforts somewhere else. If there’s a bunch of news results, well, maybe we should consider creating a blog or a news section that could be in Google News. If there are image results, well, maybe we should consider visual content, right? All these kinds of different search results that Google’s showing in different positions, need to bias your keyword efforts. You need to bias your SEO efforts and your content efforts. If they don’t, you can spin a lot of wheels with not a lot return.

Roger Dooley: That’s great advice. Would you think things are going to change much in the next year or two, Rand?

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, yeah, I think so. What we’re seeing with Google right now is, I think last week, we saw the first example of Google showing a zero organic results search query.

Roger Dooley: Wow.

Rand Fishkin: For things like time.

Roger Dooley: That’s scary for many folks.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah, right. And this is for … it’s a toe in the water, right? They did it for something like, time in London, or time in Los Angeles, or time and date LA, or those kinds of queries, which yeah, most people are just looking for the instant answer. The click-through rates probably very small, but I bet it wasn’t zero. You know, there were still people, who were ranking there, who were getting thousands of visits a month and now no one’s getting anything except Google.

I think Google’s training users that they’re becoming more the answer and the content, rather than how you find the answer and the content. That is a shift. We also saw, starting in the summer, it was summer of last year, for the first time ever, we saw the number of total clicks that Google sent out organically, declined. That’s never happened before, as far as we know, right? This is from Clickstream data providers. Meaning, there’s a slightly smaller share of opportunity.

Now, granted, it’s still … you know, if you and I were having this conversation in 2015, we’re still talking about four or five times the amount of total opportunity in 2018, so it’s gone down a very small amount, but still way up from …

Roger Dooley: It could be a harbinger of things to come.

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, yeah. That’s I think the scary part, right? Is that opportunity to gain search traffic is shrinking for the first time ever. It’s still massive, but it’s not growing the way that it used to. And that’s not because number of searches is not growing, that continues to grow. It’s because of how Google’s displaying results.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Hey, we could go on and on here and I’d love to do that, Rand.

Rand Fishkin: Sure, absolutely.

Roger Dooley: But, let me remind everyone that today, we’re speaking with Rand Fishkin, founder of SparkToro, co-founder and ex CEO of Moz and author of the new book, Lost and Founder, a painfully honest field guide to the startup world. Rand, how can people find you and your stuff online?

Rand Fishkin: Yeah, you can find me on sparktoro.com, run a blog there and you can … my most active network is Twitter where I’m @randfish.

Roger Dooley: Great. Well, we will link to those places and to the book and other resources we mentioned on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. There will be a text version of our conversation there too. Rand, thanks for being on the show and good luck with both the book and your new venture.

Rand Fishkin: Thank you so much, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.