The concept of the starving artist is so widespread that sometimes it’s hard to imagine anyone—other than a few outliers—really succeeding in their craft. But Jeff Goins says we shouldn’t buy into that idea, and that it’s actually much more possible to succeed as an artist than people think.

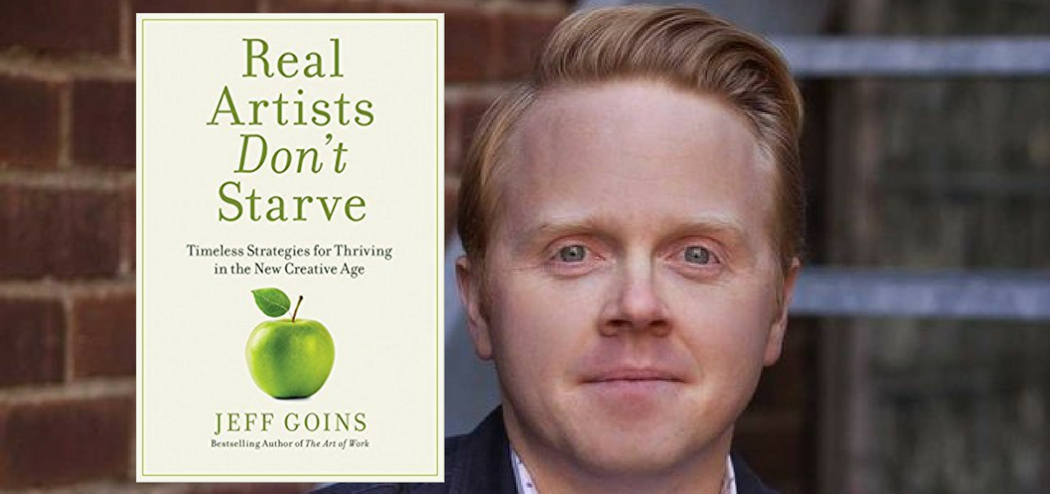

Jeff Goins is a writer, speaker, entrepreneur, and the best-selling author of five books, including The Art of Work and You Are a Writer (So Start Acting Like One). His award-winning blog Goinswriter.com is visited by millions of people every year, and through his online courses, events, and coaching programs, he helps thousands of writers succeed every year.

Hear key advice for any serious artist who wants to get their career off the ground with @JeffGoins, author of REAL ARTISTS DON'T STARVE. #creativity #art Share on X

In this episode, Jeff shares insights from his new book, Real Artists Don’t Starve, and explains why we shouldn’t buy into the concept of all artists struggling to make ends meet. Listen in to hear his advice for any serious artist who wants to get their career off the ground.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why the statistics of artist success rates don’t necessarily provide an accurate picture.

- One of the important first steps to becoming an artist or entrepreneur.

- The approach to entrepreneurship that provides the most success in the long run.

- Jeff’s evolution as an artist.

- Why he says there’s never been more opportunity for apprenticeship and mentorship than today.

- Why an apprenticeship no longer means you have to have direct physical contact with someone.

- How to go about beginning a mentor relationship.

- The most important decision you’ll make for your work.

- How where you live affects the work you do.

- Jeff’s take on self-publishing vs. working with a publisher.

- Key things to consider before selling the rights to your work.

Key Resources for Jeff Goins:

-

- Connect with Jeff Goins: Blog | LinkedIn | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

- Amazon: Real Artists Don’t Starve

- Kindle: Real Artists Don’t Starve

- Audible: Real Artists Don’t Starve

- Amazon: The 10% Entrepreneur: Live Your Startup Dream Without Quitting Your Day Job

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. I think if we did a word association test right now and I threw out the word artist, the most common answer might be starving. Our guest this week is a creator of art himself, in this case, books. Jeff Goins is a speaker, teacher and entrepreneur too. Through his online courses, events and coaching, he helps thousands of writers succeed every year. He’s written five books, including the Art of Work, and his newest book aims to put the starving artist myth to rest. It’s appropriately titled Real Artists Don’t Starve: Timeless Strategies for Thriving in the New Creative Age. Jeff, welcome back to the show.

Jeff Goins: Hey, Roger. Thanks for having me. Good to be here.

Roger Dooley: To get this rolling, Jeff, what does your own evolution as an artist look like?

Jeff Goins: Well, when I was a kid, I used to draw cartoons of Garfield the cat. Then when I was a teenager, I used to write music, mostly sad songs based on girls who had dumped me or just refused to go out with me in the first place.

Roger Dooley: Plenty of material.

Jeff Goins: Yeah. Then in college, I was a member of a few music groups, bands, and actually when I graduated college, I toured most of North America and had a little stint in Taiwan for about a year. Every step of the day, especially when I was a professional musician, people would say really nice well meaning things to me like, “Hey, this is really good that you’re doing this now, because everybody knows you can’t make a living doing that.”

I just had this idea, and I wasn’t bitter about it, I just thought it was true. I just had this idea that if you were going to do creative work for a living, you’re going to starve, that was not going to work. You’re going to have to find some other commercially viable career option other than making art, making music or even writing.

When I was working for a nonprofit as a marketing director, and I had this itch to write, I didn’t think I could make it. I thought this would just be a hobby. About 18 months later, I had quintupled my salary as a nonprofit marketer, which isn’t that hard to do in New York in the nonprofit world, but I had effectively more than replaced my income, I’d replaced my wife’s income, and really changed the course of not only my career, but the course of my family and all of our lives. That’s been a course that we’ve been on ever since for the past six or seven years. It was all because of writing, because of this thing that relatives and professors and teachers mostly told me, “You can’t make any money doing that.”

Roger Dooley: Right. I guess maybe the numbers on average might somewhat bear that out. Jeff, I’ve always assumed whether we’re talking some kind of visual art or music or writing is a little bit like professional sports or acting in Hollywood, lots of people aspire to support themselves that way. A small number manage to barely support themselves by maybe combining a variety of gigs and doing things. Then there are a few that actually succeed financially that way, but it’s really a vanishingly small percentage. I think you would at least somewhat disagree with that, right?

Jeff Goins: I would disagree with that for a couple of reasons, like, there’s layers to it. One, anytime you read a poll or any sort of statistics about this kind of thing, how many artists, how many of the writers are making a full time living, writers is a big one, and it’s like, you know, .1% or whatever. The first problem with that data is these are not, like, anybody who considers themselves a writer is somebody who maybe has self-published a book at one point, and millions of people a year are doing this now. Not all of them are trying to do this full-time. Many of them, this is just a hobby, this is something they wanted to do on the side.

That’s sort of stipulation number one. To be a plumber or a doctor, whatever, there’s other things that you have to go through to be certified to do that kind of work, and so that like, how many plumbers make more than $40,000 a year, those numbers are going to be different, because to be a writer, all I really have to do is say that I’m a writer and write, and maybe make some part-time side income doing that.

That’s one way in which this sort of gets skewed, is you’ve got a lot of people doing this activity going, “Well, I’m not making any money doing it.” Well, this isn’t your job. If it were your job, you would obviously take it a lot more seriously.

The second reason why I don’t love that analogy to say professional sports, is it is really hard if you play football or soccer or baseball to go outside and start doing your craft in front of people and get paid for it. It’s next to impossible, right? You could teach it, you could join a team if somebody thinks you’re good enough. Of course, you’re limited by the number of people that can be on a team or be in a league. There’s some serious limitations to making money in professional sports just because it’s based on entertainment, entertaining people that pay money to go to stadiums and watch these sports on television.

Roger Dooley: I guess you’d say both the ability to perform or conduct your past time as well as access to audiences is a lot better for writers or visual artists than it is for would-be sports players.

Jeff Goins: Absolutely. Grab a guitar, go outside, get a guitar and start playing. If you’re good, you will attract fans. If your guitar case is open, you might even generate an income. The last thing I want to say on this is, there is an interesting study, I think it’s conducted by Indiana University I think, it’s called the SNAAP study, S-N-A-A-P. It’s basically a survey all over the United States that they do every year, and they survey graduates of arts programs. This is not artists or creative people, but it’s a decent representation of people who have studied a creative field and then have used that education to go into the workplace.

The statistics are fascinating. Most art students, you know, graduates of arts programs are not doing any worse than those who have gone into the more science, math-based field, and a lot of them are doing a lot better. The interesting thing is, the vast majority of them, 80 to 90% say they’re very, very happy in whatever their chosen field is, and 80 to 90% say they’re using their creativity in the work that they’re doing today.

The question is not am I going to starve as an artist. I think the question that we face today is am I going to do my creative work, whatever that is, because I think the opportunity to do that kind of work is better than ever. I think the opportunity to attract an audience is easier than ever. I think whether or not you starve today is really a decision that’s left up to you.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I suppose one key step is really sort of self-identifying as an artist. I know I didn’t really consider myself an author, I didn’t call myself an author. I guess if somebody said, “Are you an author,” I’d say yes because I have a book from a major publisher. I didn’t really, I consider myself more of an entrepreneur who wrote a book, something more along those lines. Probably one key step for any would-be thriving artist is to self-identify as whatever they want to be, right?

Jeff Goins: I think so. I think that we tend to become what we think about. If you think, I’m an amateur, if you think, I’m not a writer, then you’re going to act like somebody who’s not a writer. If you think, I’m not an entrepreneur like those people are entrepreneurs, this is a thing we always say because we go, like, you Rodrigo, I wrote a book but I’m not a writer like Stephen King is a writer. Well, if that’s the baseline, then we’re all out of jobs.

The same thing is true for being an entrepreneur. I’m not an entrepreneur in the way that Richard Branson is an entrepreneur. That’s okay. You’re you, right? The question is, are you going to do this or not? Do you want to do this or not? If so, it really begins with a question of identity. We become who we think we really are.

In the book, I tell the story of Michelangelo who was the richest artist in the Renaissance, something that not a lot of people knew about until recently. What he did in the Renaissance was he made it possible for an artist, which was like a working class Joe, to become an aristocrat. He broke that glass ceiling in his lifetime, and there were many, many successful and wealthy artists in the Renaissance and beyond after him. This whole notion of a starving artist is really a much more modern creation.

Anyway, in the life of Michelangelo, he grew up not having a lot of money, but his family told him a story, they told themselves a story that they believed was true, which was that their surname, Buonarroti, comes from nobility. They were from a noble family. Michelangelo grows up thinking, he was the bread winner of the family, his older brother went off to become a priest, and so he became the next in line to provide for the family. When he decides to become an artist, there’s this pressure on him to provide for the entire family. He has to think about his chosen vocation differently than everybody else is thinking about it, because at the time, as I said, artists are like merchants, they’re just these working class guys.

He decides, well, we’re from nobility, so I have to do the things that it takes to be a noble artist, to be an aristocrat, and he does. He works with popes and princes, he says in a letter, “I never kept a shop like many artists do.” Everything he does, even the way he addressed, he was trying to set himself apart as someone different from everybody else, and it ends up becoming true. He becomes the richest artist of his time.

Here’s the really interesting part, Roger. He wasn’t from nobility. Years later, most historians agree the Buonarroti family, Michelangelo’s family was not from noble blood. They don’t know where they got that surname. In that time, if you had a last name, you were somebody important. They don’t know exactly where that came from, but it wasn’t connected to nobility. Because he believed it, because Michelangelo believed a story that he grew up telling himself, it became true.

If you want to be a writer, you want to be an entrepreneur, you want to be an artist, I think one of the first steps is to begin to call yourself that thing, and then very quickly start acting as if that’s true.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Just to hit in the other direction before everybody goes out and quits their day job to do art, one of the points you make early in the book is that it isn’t necessary to do that, to suddenly go all in on whatever your preferred art form is, and that it’s okay to do it gradually and test the waters.

A while back, we’ve been talking about the similarity between artists and entrepreneurs. We had Patrick McGinnis on who wrote a book called The 10% Entrepreneur, and he talked about the success of entrepreneurs who did not go all in, but they had a chance while they still had a day job, and actually, that’s his recommended approach. Now, obviously in certain cases, if you, like, millions in venture funding or something, different story, but that for many kinds of startups, doing it gradually, doing your research, doing that sort of initial testing, will somebody pay money for this is much better than quitting your job, going out, just flaming out in six months because you’re out of resources. I guess you would advocate something similar for art, right?

Jeff Goins: I wholeheartedly agree with that. Whether you’re an artist, musician, entrepreneur, it’s all the same thing. You’re working for yourself, right? An artist is an entrepreneur. A writer is an entrepreneur. If you’re going out and going to do this thing as your own entity, you are a self-employed person who’s running some kind of organization, even if it’s just an organization of one. I’m a big advocate of not taking a leap, but building a bridge, and building on that story that you’re sharing.

There was a study that was conducted at the University of Wisconsin, where they followed something like 5,000 American entrepreneurs for over a decade, and they followed their careers. They followed the success of their businesses. They had two groups of people, they split it into group A and group B.

Group A quit their jobs and then started a business. Group B kept their jobs and then started a business on the side. They’re obviously spending less time focused on the business and they gradually grew the business, and then once it reached a point of success, then they eventually went full-time with it.

Here’s the interesting thing about it. You’ve got group A, much bigger risk takers, and this is what we’re told, especially in America, this is what it takes, or you know, in any westernized country. This is what it takes to succeed, is you’ve got to go all in, especially in entrepreneurship.

Then you’ve got group B who kind of did it gradually, maybe the way your mom would prefer that you did it. Group B was twice as successful as group A. Their failure rate was half as much as group A. The numbers speak for themselves. Whether it sounds thrilling or not, the smarter move for most of us is to build something gradually one step at a time.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). I would imagine too, any form of art, whether it’s writing or visual art is to some degree like business. You don’t really know what’s going to work for you, you don’t know what’s going to work for people who might be your customers or your patrons. If you go all in all at once, you’re under tremendous pressure to make it work right away. You don’t have time to experiment in small ways. I think that makes a huge amount of sense, Jeff.

Now, something else you talked about as a way of learning a craft is to apprentice with a master. Now, in Michelangelo’s time, that was a pretty well accepted way of doing things, and even probably on into the beginnings of this century. These days, the whole concept of apprenticeship seems to be a little bit lost. I’d like to apprentice under Malcolm Gladwell, but I don’t think he’ll let me hang out with him and maybe judge my writing every now and then. I’m curious whether you had any mentors or you had any sort of apprenticeship, or in general, how would you advise people go about finding somebody who can help them?

Jeff Goins: You’re right, Roger, in that it’s less accepted now, formal apprenticeships than it was 500 years ago, say in the days of Michelangelo where it was common practice that if you were a young man wanting to learn a trade, you would typically go ask to be apprentice or be approached by someone and be asked to study under a master, usually for seven to eight years, often for free in exchange for sometimes room and board, but mostly just for an education. Then you’d go off and you’d travel on your own in your journeyman phase, which would be another two to three years.

Then you’d come back home or you’d settle down somewhere and you’d create what was called a masterpiece, and you’d submit to the local guild and they would say, “Oh, yeah. He’s got what it takes. He can join the guild and I’ll be a master and take on new apprentices.” That’s how it worked. It’s a lot less formal these days.

On one hand, it’s a lot less accepted. On the other hand, there’s never been more opportunity for apprenticeship than today. What I mean by that, this podcast is a collection of ideas that most of your listeners would not otherwise have access to. It is an opportunity to apprentice. How many shows, how many blogs, how many opportunities just through the internet are there to learn from truly, true masters of the craft? You may not be able to sit in a café with Malcolm Gladwell and watch him write, but you could pay $100 and watch his master class online and hear him talk about his own writing process.

This opportunity to get an education from the very people who are at the very top of their profession, it has never existed before. Yet, we have these people going, well, you know, I just can’t get lucky. I can’t succeed. It’s easy for you, it must be nice for you.

I think what we have today, Roger, is we’ve got, a lot of people want to be a master, but nobody wants to be an apprentice, and mastery always begins, I mean, 70 to 80% of the process during the time of Michelangelo was humbling yourself, being a student of somebody else’s work. We have an embarrassment of riches of content and educational opportunities, ways to learn from those who are truly great at their crafts, and yet a lot of us are content to do our own Facebook lives and blogs. I’m not against that, right, but there’s a time to humble yourself and learn, and then there’s a time to share what you have learned. Many people are not taking the first step to simply humble yourself and learn.

The second answer to that question is absolutely. Absolutely I’ve enjoyed many relationships with people that I would consider masters of writing, of business. Some of these people have become friends of mine. Some of them I’ve met up close and personal, many of them I’ve met, I’ve started with a relationship online, reading their blog, listening to their podcast, studying what they’ve done and why they did it. I think if you do this and you do this well, these masters, the people in your life that have influenced you that you want to notice you, they will start to pay attention to you if you simply go, “Hey, I’m listening. I’m paying attention.”

Certainly not everybody. I don’t know if Malcolm Gladwell is ever going to email you Roger and say, “Job well done,” but there are masters out there who are simply waiting for somebody to do the work, to become a case study. I’ve seen this work over and over and over again with people who are heroes of mine, and I email them, I said, “I read your book, and I started the blog, and I did this thing, I did this, this, this, this, this. I’d love to buy you a coffee sometime,” and they go, “Okay, cool.” That started a friendship.

I think the way that we get this wrong a lot these days when we want to be a person of influence is we go, “Hey, can I pick your brain,” and that’s not the way this works, and it’s not the way it worked for Michelangelo or his predecessors. You had to demonstrate that you were worth investing in, and then, you do the work, and then you reach out and say, “Hey, I’m already doing the stuff that you talk about. What else do you have for me?” That’s how you begin an apprenticeship relationship. You do this with lots of people, and some of those people will want to engage with you in that process.

Roger Dooley: I think there’s two key takeaways there, Jeff. I think one is that first of all, in the 21st century, apprenticeship doesn’t have to mean a direct physical relationship with somebody. You could be learning from them from their online content, from their books, from other sources. That’s stage one.

Then also, we do have the tools today to reach out to people. You could probably reach out to just about anybody, since we’re both writers, we could reach out to any author that we can name. We can find a way to do it, we could probably track down their email address or their social media account. The key thing is I think that if you’re going to do it, really, you have to show that you’re prepared, that you’ve done your homework, that you understand them and their work, and then maybe reach out, not just, “Wow, hey, love your stuff. Can we talk sometime?”

Jeff Goins: Yeah. Absolutely.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure you get a ton of that. I get a little bit of that. I would guess somebody like Gladwell or Stephen King, it’s like 100x or 1,000x of what we get. I think cutting through the noise by really showing you’ve done your homework is generally the best approach.

Jeff Goins: Yeah. Here’s an example. A friend of mine, a guy named Ray Edwards, copywriter, online marketer, has worked with people like Tony Robbins, Michael Hyatt, and done a lot of solid work and has a fairly large audience, and sent an email out to his email list which had to be over 100,000 people and said, “Hey, I want to tell your story.” He basically made, he said, “Hey, I want to feature you as a case study on my blog, one of my readers who’s done the work, and he teaches people how to start online businesses.” He’s like, “Here’s the 20 things that you have to do,” right? Do the YouTube video, and basically itg was like, you have to promote Ray.

This guy, or another friend of mine named Mike Kim does it, he does all the stuff, he emails Ray and he goes, and it was a contest, like, do all this stuff and then one of you will win, whoever does it the best. Mike does all 20 steps, and he emails Ray and he goes, “Hey, I did it. Here’s all the things that I did. Did I win?” Ray goes, “What? You did all those things?” He goes, “Yeah, yeah. Did I win? How many people did it? How close is it?” He goes, “You’re the one. You’re the only one who did it.”

I think it’s easy to talk about this stuff, it’s harder to do it. If you are the one that actually does all the work, you’re going to rise to the top a lot faster than you think. Because yes, there are a million people asking that influencer for some time, there’s a small, small fraction of those people who are actually doing the work, doing what they say. Pretty quickly, the cream will rise to the top.

Roger Dooley: I think one thing that carries over from the ancient apprenticeship days too is that the apprentices have to deliver some value to the master. In those days, maybe it was keeping the studio clean or fixing the meals or painting backgrounds that weren’t too important. Today, it might mean something else, but it can just be a one-way street.

Jeff Goins: Yeah. I agree. Having a podcast is a great way to connect with people that you might otherwise not be able to talk to. I have a podcast, and about 90% of the reason I do it is because it affords me opportunities to talk to people that, I’d think twice if I just emailed them and said, “Hey, let’s talk.” But if I say, “Let me interview you on my podcast, try to bring some exposure to the work that you’re doing,” that’s an easy yes for them, it’s easy to justify that time. But we end up talking about a bunch of different things, and I benefit from that experience. You’re absolutely right. You’ve got to bring value. Again, I think with tools like podcasting, blogging, social media, the opportunity to do this is better and easier than it’s ever been.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Jeff, jumping over to the concept of place, historically that’s been pretty important for artists by bringing them in contact with other people who are doing the same thing that they are perhaps differently or perhaps better, van Gogh moved to Paris, actually I think van Gogh was just one of several folks that moved to Paris that you describe in your book, and you give a shout out to my hometown of Austin which has been a great creative city.

One thing we’ve seen lately is that what’s happened in say Greenwich Village in New York or San Francisco, and now it’s happening in Austin too is that artists congregate in a place, they make it cool, and then people with money start moving in and it becomes impossible for artists, even if they’re not actually starving, they aren’t investment bankers and they can’t afford to live in that place anymore. You’ve been studying this for a while. Is that kind of evolution an inevitable?

Jeff Goins: I think so. I mean, if you look at every city that was Bohemian hub at some point, you’ve got Paris, Paris had kind of a couple of different golden ages. There’s the 1850s where all the impressionists are there, and van Gogh comes there at the tail end of that. You’ve got Monet and Manet and Renoir and these guys, Cezanne.

Then you’ve got the modernists who like, 50, 70 years later, you’ve got people like Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, you’ve got a bunch of writers and you also have Picasso and Hemingway. They all moved there, and it becomes this hub for them to learn from each other and help each other succeed.

Well, in the 1920s, Paris, there’s people walking through the streets with goats. Hemingway talks about getting up in the morning and seeing the goat herd walking through the Left Bank. You go to Paris today-

Roger Dooley: I was there last year and I didn’t see any goats in the streets.

Jeff Goins: Yeah. I mean, it’s inevitable. New York City, Paris, San Francisco, I do think there’s some inevitability about it. Nonetheless, if you want to do any kind of work, the environment around that work can help or hinder the work, and there’s lots of great research on this. … in his classic scholarly work on creativity called Creativity, said it’s easier to move, to change your environment, if you want to be more creative, move. It’s easier to do that than it is to will yourself to be more creative. I call this a scene. It’s a place where creative work is happening, the kind of work you want to do. In the same way, you’ve got San Francisco, Silicon Valley, you move to certain places to do a certain kind of work.

However, as you mentioned, these places tend to get oversaturated and it’s hard and probably not the best choice for an artist or even an actor these days to move to New York City. I spoke to a musician who moved to Nashville, and it was like the worst business decision for her ever, because when she lived in Minneapolis, you could get paid to do live local shows. When you move to Nashville, everybody’s willing to do the work for free because there’s so many musicians here.

The rule I think is this. You need a scene. Hands down. You need some sort of environment, it’s preferable that it’s physical. You can sort of stimulate it online, but it’s ideal if you’re in a place where you’re bumping into the kind of people who are doing the kind of work that you want to do on a fairly regular basis. You either have to join a scene or create one. Both are legitimate ways to do it.

If you go, I can’t move across the country, or, the kind of work I want to do, all these areas are oversaturated, then create a scene. Find a group of people in your local network and bring those people together around some sort of cause. I think this happened in Nashville about 10 years ago, not necessarily intentionally other than just people who are interested in doing online business, online marketing, of which I was a part, all started congregating and hanging out together and stuff started to happen.

In the book, I tell a story about an artist named Tracy who moves away from New York City and moves down to Arizona and creates this little cluster of creatives, and they all make each other’s work better.

Where we live and do our work affects the work that we do. How can it not? I spoke to Richard Florida about this, he did a lot more research on this than I have. He said the most important decision you’ll make in your work and in your life is where you choose to live. It’s not so much about going to that one place where this kind of work can happen as it is being aware of your environment and asking yourself, is this environment helping or hindering the work that I’m trying to do, and then, what can I do about that. Do I move? Do I need to create a scene here, because genius is not an isolated solitary experience, it is a group effort.

Roger Dooley: Something else that you talked about Jeff is the concept of owning your work, and in general, it’s good for artists to own their work, but sometimes there’s a right time to sell it. I’m curious, one thing that we both deal with is when you write a book, the publisher tends to control many if not most or all of the rights. Where do you fall in the publishing, well, working with a publisher versus self-publishing debate?

Jeff Goins: Well, I think most published authors who, I worked with a publisher on four out of five of the books I’ve written. Like most authors, I have my frustrations with every and any publisher I’ve worked with. Like I say in the book, it’s not so much that you never sell out, it’s that you shouldn’t sell out too soon. When we’re talking about a book, you sell a book to a publisher, you’re literally selling them the publishing rights, right, so that they should be making most of the calls, they own the work. You should do that for what you think is a lot of money, right?

I sell a book to a publisher for more money than I think I can make off the book in the next two or three years, not like forever, but the next few years because I can take that money, I can invest it in my business, I could pay off my house, I could do whatever I want with that, and then still have the freedom to keep writing and still keep creating other things that I can sell.

I find a lot of creatives, especially writers, sell off their work too quickly to a publisher, they sell their businesses, and they’re not thinking long-term. The bottom line is, once you sell that work, that book, that business, the songs that you’ve written, you do not own them obviously, and therefore you do not control them.

There are fascinating stories of people like George Lucas and even John Lasseter who started Pixar who waited and waited and waited and turned down great deal after great deal after great deal. Not for the money, they could’ve sold out a lot sooner, but so that they could maintain creative control of their work until it made sense to sell it to somebody who was going to make the work better and last longer and therefore reach more people.

I think Pixar is a great example of that. John Lasseter leaves Disney because they’re not being very creative, helps start Pixar with Steve Jobs and company, and then Disney offers to hire him back for triple his former salary, and he says, “No, I’m having fun,” and continues to grow and nurture Pixar, and then eventually they take Pixar public, and eventually Disney buys it back, but they do it with these very, at this point, Pixar’s ruling the animation scene, and they do it with these stipulations that they’ve got to keep all the animators at Pixar maintain this creative control of all their work and they’re able to protect the work.

I’m not somebody who says you should always own your IP forever. If you could partner with somebody and you could do it for the right amount of money and they’re going to help make the work better and spread farther, that’s why you should work with a publisher. That’s why you should sell your business. That’s why you should partner with somebody or some entity so that it serves the work. In most cases, lots of people do this way, way, way too soon.

Roger Dooley: Right. I’ve got a story that didn’t make it into your book, Jeff. On an earlier episode, I spoke to Tom Peters, one of the best selling business book authors of all time. The story behind his In Search of Excellence book was he and his co-author were partners at McKenzie at the time and they were working for McKenzie, this was an outgrowth of one of their projects, and the conclusions of the book really didn’t fit the McKenzie strategy at that point and apparently relations were a bit strained, and Tom ended up leaving before the book even came out. He managed to secure his half of the royalties, which at that point, and he actually had to pay $50,000 as part of his exit package to get the right to those royalties.

At that point, they were planning a print run of 5,000 copies, which for a business book was pretty typical, and nobody knew if we’d even sell that out. It turns out that was probably the best investment he’d ever made, because within a year, it had sold a million copies, and within three years, within three or four years, it sold a couple million more. That was apparently a case of having confidence in your work and doing what it would take to keep the ownership of it.

Now, they’re not all going to turn out like that one, but that was really an amazing story.

Jeff Goins: Yeah, that’s incredible. I mean, I think the lesson is to keep betting on yourself. Obviously not all bets pay off, but some of them do, and some of them pay off big time. Even when they don’t pay off, what you’re fighting for is not, you’re not gambling, you’re not hoping that you’re going to win the lottery, you’re fighting for creative control because nobody is going to care about this project as much as you do, because it’s yours.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Definitely. We’re just about out of time, Jeff. Let me remind our listeners that we are speaking with Jeff Goins, best selling author of the new book, Real Artists Don’t Starve: Timeless Strategies for Thriving in the New Creative Age. Jeff, how can people find you and your work online?

Jeff Goins: Well, thanks, Roger, I really enjoyed it. You can find me at my blog, GoinsWriter.com. You can learn more about me and my books there, also sign up for my email list and get some free stuff. I talk about writing ideas and making a difference, so if you want to see your creative work spread, you can go to GoinsWriter.com, that’s G-O-I-N-Swriter.com.

Roger Dooley: Great. We will link there and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at RogerDooley.com/podcast. We’ll have a text version of our conversation there too.

Jeff, thank you. It’s been great to have you back on the show.

Jeff Goins: It’s my pleasure, Roger. Thank you.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at RogerDooley.com.