Have you ever caught yourself daydreaming, and then mentally scolded yourself for wasting time? Well, next time, don’t be so hard on yourself. My guest today is here to explain why wasting time isn’t such a bad thing. In fact, he says it’s necessary for creativity, self-identity, and overall health.

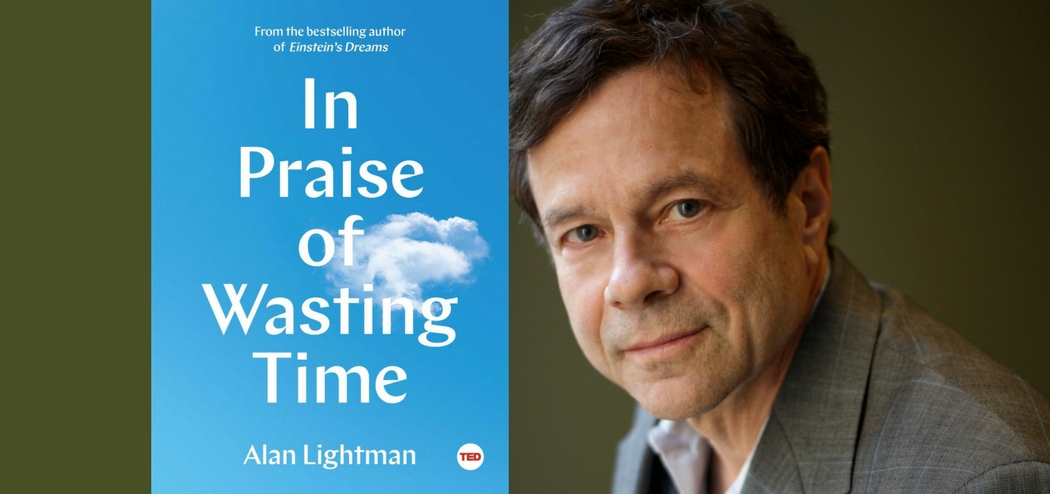

Alan Lightman is a physicist, novelist, and essayist with a Ph.D. in theoretical physics from Caltech. One of the first people to receive dual faculty appointments in science and in the humanities at MIT, Alan is the author of five novels, two collections of essays, a book-length narrative poem, and several books on science. His novel Einstein’s Dreams was an international bestseller and has been translated into thirty languages.

Learn why we should all be wasting time with physicist, novelist, and essayist Alan Lightman. #creativity #timemanagement Share on X

His new book is In Praise of Wasting Time, and he joins the show today to share the truth about the importance of downtime. Listen in to learn how to make sure you give yourself the mental breaks you need and why we should all be wasting time every day.

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- Why Alan says life in today’s society is unhealthy.

- What’s responsible for the decrease in creativity over the years.

- The problem with not letting our minds wander freely.

- Activities that can engage your background processing to promote creativity and help you problem-solve.

- The healthy habit Alan recommends everyone adopt to improve creativity and self-identity.

- What companies have done to improve productivity and efficiency among employees.

- The major problem with the “time is money” mindset.

- Advice for balancing downtime with consciously productive time.

- Tips for those who want to think more effectively.

Key Resources for Alan Lightman:

-

- Connect with Alan Lightman: Wikipedia | MIT Page

- Amazon: In Praise of Wasting Time

- Kindle: In Praise of Wasting Time

- Amazon: Einstein’s Dreams

- Amazon: Faster

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley, author, speaker and educator on neuromarketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week, we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to The Brainfluence Podcast. I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week has a fascinating and diverse set of accomplishments. Alan Lightman is a physicist, novelist, and essayist, has a PhD in theoretical physics from Cal Tech, and before coming to M.I.T., where he currently is on the faculty, he was on the faculty at Harvard University. At M.I.T. Alan was one of the first people to receive dual faculty appointments in science and in the humanities.

Alan is the author of five novels, two collections of essays, a book-length narrative poem, and several books on science. His novel Einstein’s Dreams was an international bestseller and has been translated into 30 languages. Alan’s new book is In Praise of Wasting Time.

Welcome to the show, Alan.

Alan Lightman: Nice to be here, Roger.

Roger Dooley: With your writing output and academic work, Alan, from the outside it looks like you haven’t been wasting much time yourself, but that’s not entirely true, right?

Alan Lightman: Well, my wife always has been joking with me for the last year when I’ve been working on this book about wasting time, because she says that I don’t waste any time. But, actually, I do waste a fair amount of time. My wife and I every summer retreat to an island on the coast of Maine, and there’s no ferry service, no telephone lines, no boats, no bridges. My wife is a painter, and we spend three months there, I guess you could say, wasting time, not doing any scheduled activities.

Roger Dooley: Right. I love that you live close to Walden Pond and get to walk the same paths that Thoreau did. I think that kind of encapsulates the essential problem you define in the book. Today Thoreau couldn’t just be sitting out in a cabin thinking and writing. He’d have to be interacting on Twitter with his followers. He’d be posting duck photos on Instagram, scheduling podcasts, managing a Facebook group, guest-posting on other people’s blogs, and pretty much everything else that a published expects an author to do today. It’s not just authors. It seems like we’re all pulled way too many directions, don’t you think?

Alan Lightman: Yeah. I think that the world is moving too fast for its own good, and I think that the pace of life has always been driven by the speed of communication. The speed of business is controlled by the speed of communication. In 1985, near the beginning of the public internet, the speed of communication was about a thousand bits per second, and now it’s about one billion bits per second, a million times faster.

Everybody who’s alive in the world today, especially in the developed world, knows that things are moving faster and faster. We’re dividing up our day into smaller and smaller units of efficiency, and we’re plugged into the grid all the time. We take our smartphones with us on walks through the woods. We check our email when we’re at restaurants. We’re just rushing all the time to keep up. I think it’s unhealthy for us.

Roger Dooley: It’s funny. Years ago I read James Gleick’s book titled, oddly enough, Faster, and he wrote about how everything was speeding up and how crazy it was getting. But that came out in the year 2000. That was before the mobile revolution, before social media had a major impact, and a lot of the other stuff that we’re talking about; but, from that perspective it was, like, “Wow, things are really moving quickly now.” It’s just really gotten so much more intense.

Many of our listeners have an interest in neuroscience, and one of the topics you discuss in the book is that brain scans show our minds are using as much energy when we’re at rest as when we’re actively problem-solving. Did I get that right? What’s going on here?

Alan Lightman: Yeah. Well, it used to be before around 1940 or ’50 that we thought that the sleeping mind, or the sleeping brain, or the resting brain was very quiet, but studies done from the 1950s on have shown that there’s almost as much activity that takes place in the resting brain as in the active brain, which just says that even when we’re resting, or we think that we’re resting, that the unconscious brain is doing a lot of work. This is probably associated with creativity, which researchers, although not brain scientists, have known for a long time that creative people often do their best work and their best thinking when they are not consciously focused on a problem, but letting their unconscious mind spin along on a problem.

The composer Gustav Mahler used to take three or four-hour walks after lunch and jot down musical ideas. Einstein said that his best thinking was when he let his mind just run free and roam. So, this is one of the problems of our plugged-in, wired existence today, that we’re not letting our minds just wander freely. We are focused on our to-do lists, and our tasks, and our schedules 24/7, and there’s very, very little time to unplug and to just let our minds spin along.

Roger Dooley: I guess it’s pretty hard to do that if you’ve got your phone in your pocket, and it’s constantly buzzing with little notifications that you’ve got new mail, or you’ve got some kind of social ping coming at you. At the same time, most people treat that as a desirable thing. They may give some lip service to, “Wow, it’s kind of distracting,” but that doesn’t mean they turn their phone off. So, it makes that sort of quiet time, or even just an interrupted walk or something, a lot less likely to happen.

Alan Lightman: Yes. Researchers have looked at, done longitudinal studies of creativity using something called the Torrance Test of Creativity that was developed in 1965 and have found that over the last two or three decades, since the emergence of the public internet and especially the smartphone, that creativity has gone down, and especially among young people. The conclusion from this by the researchers is that it has been the internet and the 24/7 wired nature of our existence, looking at our smartphones every two or three minutes to see what messages have come in, that the lack of quiet time for reflection and slow turning of the wheels, that that is the culprit for the decrease in creativity that’s been seen.

I think that there are other problems caused by our frantic wired existence and not just diminishment of our creativity. I think that the mind needs to replenish itself, that we need quiet time, private time to replenish ourselves, to think about who we are and where we’re going. If we’re rushing around all the time, just picking up our latest email, sending out another text message, we’re not able to think about what our values are, what’s important to us, both as individuals and as a society. I think the entire country … This is true of a lot of Western countries, not just the United States … has lost sight of where it’s going. We’re just rushing, rushing, rushing. We’re on a train that’s moving very fast, and we’re not looking to see where we’re going. What’s important to us? What do we want out of life?

Roger Dooley: I think even at maybe not quite that grand of a level, I think that we’ve all probably had that experience where we’ve got something important to work on that’s really kind of important to our life goals, or perhaps it’s meeting a book deadline, as you’ve had to do multiple times. You start the day with great plans to make progress, and by the end of the day you realize that you’ve been basically responding to-

Alan Lightman: Emails.

Roger Dooley: … events that happened all day or were thrust at you, and your progress on that important goal is zero. At the same time, you were very busy the entire day.

Alan Lightman: Yeah. I mean, we’ve developed a mindset where we need that external stimulation all the time, or we’re afraid we’re not going to keep up. Psychiatrists have looked at this, and there’s been an increasing rate of depression among teenagers, which has been documented. The cover of the November 9, 2016 Time Magazine was all about this, had a picture of a wretched-looking teenage girl on the cover.

Depression among young people has been increasing, and the psychiatrists attribute that to fear of not keeping up, or fear of missing out. They have, actually, an acronym, FOMO, F-O-M-O, fear of missing out. What they’re afraid of missing out on is the frantic activity of the internet, the checking emails and text messages every two or three minutes. That certainly does not leave any time for reflection, for, as you say, getting the one major project that you wanted to do that day done. If you’re just responding to external stimulation, in fact, needing that external stimulation like a drug, like a drug addict, then you’re a prisoner. You’ve given up your freedom. You are a prisoner. I think that many of us in the developed world that are part of the wired world, we are prisoners.

Roger Dooley: Now, we talk about quiet time, but I thought it was pretty interesting that in your book you spent some time talking about things that aren’t exactly quiet time, but they’re to some degree mental downtime, and they, too, allow for increased creativity. In one study that you cite, people who were asked to play rather simple computer games like Minesweeper or Solitaire ten minutes before a problem-solving task next did better on that task than people who just went straight to work.

Alan Lightman: Yes.

Roger Dooley: I’m wondering, is that because those games are … once you’re familiar with them … relatively mindless? I can’t imagine that, say, playing Call of Duty or Grand Theft Auto for 10 minutes-

Alan Lightman: No.

Roger Dooley: … would give you much ability to even process subconsciously.

Alan Lightman: No. What happened in that experiment … It was done by a business person. There were two groups of people, a test group and a control group, and they were both given a business problem to solve. The control group, immediately after being given the problem, set about trying to solve the problem or find solutions to the problem. The test group, after having been given the problem, for the next 10 or 15 minutes they did an activity in which their minds were not thinking about the problem consciously, some relaxing activity. In this case it happened to be a video game, but I think it could have been anything that involved play or relaxation.

That group did better on solving the problem after the 10 or 15 minutes was over. The hypothesis by the researcher is that during that 10 or 15 minutes their unconscious mind was working on the problem. So, even though it may not have been a completely quiet room where they were, they had given their mind license to play, to wander around in the rooms of their mind and just play. It’s hypothesized that that is the reason why they were more effective and more creative in finding business solutions, that they had a period of time where they were unplugged from the grid and their unconscious minds were working.

Roger Dooley: In case anybody thinks that it’s some magical power of these simple computer or video games, it was not that. There was a variation where people played the game for the same amount of time before starting the problem, but they were not told the problem until after they played.

Alan Lightman: Right.

Roger Dooley: Those people did no better than the ones who didn’t play at all.

Alan Lightman: Yes.

Roger Dooley: So, it was definitely the sort of background processing that goes on.

Alan, you talk about some creative people who had particular routines. Like, one person might straighten out their office for a while or just sort of putter around before engaging in whatever their main activity was, whether it’s writing, or painting, or some sort of business problem-solving. What are some other examples of that? I’m also curious. Do you have anything that you do that sort of falls into that category of being active, but allowing your background processing to work?

Alan Lightman: Well, I can give you one other example, and then I can talk to you about what I do. Gertrude Stein, she would be working on some writing project, and she would take a ride in the country and write a little bit and then just sit on a rock and look at some cows and then write a little bit and so on. So, she definitely needed that downtime or that time that was unplugged, in her case outside, to give her creative inspiration.

What I do is, as I mentioned, my wife and I go to an island in Maine in the summer. We take walks. I intentionally turn off my smartphone for most of the day. In fact, I’ve owned a smartphone only for a year. I resisted owning one for many, many years. When did smartphones first come out? In the early ’90s? I can’t remember exactly when. 199-

Roger Dooley: You resisted for a long time.

Alan Lightman: I resisted it for a long time, and I’m still suspicious of it. I know that it has great utility, but most of the day I keep it turned off and in a drawer. I know that everybody can’t do that, that some people need to be plugged in more than others, but I think that we can all find a half an hour or an hour during the day where we can unplug and just be alone with our thoughts. I think that’s a very healthy thing to do. I think it’s not only healthy for creativity. I think it’s healthy for consolidating our self-identity, to think about who we are and what’s important to us, and some of those thoughts are at the unconscious level. I think it’s critically important.

I think that children in grade school should begin developing this habit of mind, of silence and contemplation. I think there should be a four or five-minute period in the day of every school where people are just quiet. I think there should be quiet rooms in businesses and office buildings, a quiet room where every employee is allowed to go for 30 minutes a day, and this would not be part of the lunch break. It would be a separate thing, where no smartphones or computers are allowed in the quiet room, and employees can go and spend a half an hour there just in contemplation or quiet, alone with their thoughts.

I know that a number of businesses and companies have created meditation spaces, and that has improved the efficiency and the productivity of those employees in those companies. A person could meditate in the quiet room, but there are many other ways of being quiet and being unplugged other than meditating.

Roger Dooley: I think that even for those folks who would find, say, sitting in a quiet room difficult, that engaging in some kind of a routine activity without additional media input can be … so, for example, if it’s washing the dishes, cutting the grass … I know my first thought is, “Okay, I’m going to be doing some kind of mindless activity, so I’m going to put headphones on so I can listen to a podcast.” Not that listening to podcasts is a bad thing. We’re happy for people to do that. But it’s like I can make those minutes count; where, I’m sure that from a creativity and problem-solving standpoint, I’d be better off for at least some of that time to not turn on the TV or not turn on a podcast.

Alan Lightman: Yeah. Right. Well, I love washing the dishes. Every night my wife cooks the dinner, and I wash the dishes afterwards. I love washing the dishes, because it’s a time where I can just be quiet and let my mind roam. I’m not trying to do anything except wash the dishes. It’s a mechanical, robot-like task. I don’t watch the news while I’m washing the dishes. I don’t send emails. I just wash the dishes. It’s a wonderful time of the day, and my wife is always amazed the I look forward to washing the dishes. But that’s the reason.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure she’s delighted. Yeah, I think it’s the fact that you’re engaged in the activity, but at the same time you don’t have to concentrate that much on it.

Alan Lightman: Right. It allows my unconscious mind to go where it wants to.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Alan, you find the way that law is practiced, or at least that career is structured, to be particularly insidious. Why is that?

Alan Lightman: The law profession has this infamous category called a billable hour, or the billable minute. A lot of law firms can bill their clients in units of 1/10 of an hour. If my math is right, that’s six minutes. The reason for this, I understand, is so that every hour of a lawyer’s time is profitable. It’s for productivity. I mean, if you call up a lawyer to get advice, they’re going to bill you for a phone call. Whether it’s 10 minutes or 10 hours, they’re going to bill you for the time.

That way of thinking, that every minute is attached to a dollar sign, leads to a way of thinking in which, of course, time is money. We know that old adage. But it seeps into the rest of life, where every time you’re doing anything … even at home, when you’re away from the office … you mentally translate that period of time into how much money you would be making if you were charging your office, that every minute of the day becomes equivalent to a billable minute, and life becomes just making money.

Studies have been done to show that people who are more conscious of the billable hour … Now I’m using that phrase generally, going beyond the legal profession … that they don’t extract as much pleasure in doing simple things like listening to a piece of music. They don’t extract as much pleasure, because they’re thinking all of the time, “Couldn’t I be earning money during that hour?” I mean, they may not be thinking consciously, but unconsciously. Everything, all of life, has been translated into the billable hour or the billable minute.

Roger Dooley: Right. That time spent listening to music seems unproductive somehow, like there’s-

Alan Lightman: It’s unproductive, yes.

Roger Dooley: … an opportunity cost for listening to music.

Alan Lightman: Yeah, an opportunity cost. We want to be productive all the time. We take our smartphones with us everywhere so that we might be productive. If we have to wait around for 10 minutes at a doctor’s office it kills us, because we’re not being productive.

That’s the kind of mentality and culture that we have created in our country, and we really can’t blame technology. Technology doesn’t have a mind. It doesn’t have values. Technology is something that we created. It’s how the values come in and how individual human beings use the technology. Every time we use a piece of technology we should remember that we have a choice of when to use it and how to use it, and we are making a decision about our entire lives with that choice.

Roger Dooley: Alan, do you have any productivity techniques that sort of function in conjunction, if you’ll excuse the rhyme, with an effort to have sufficient downtime? The one that comes to mind is the Pomodoro method, where you work intensely for 25 minutes, then take a five-minute break, which isn’t necessarily the kind of downtime you were talking about. I’m wondering if, with your view on the importance of this downtime, whether you’ve found any particular approach that works for you.

Alan Lightman: Well, I don’t build in a 25-minute-on, 25-minute-off schedule while I’m working on projects. I don’t think that that’s the best way to go about it. When I’m working on a project … This is a goal-directed project, like writing an article, or preparing to teach a class, or figuring out how to manage my investments … I take as long as it needs. If it’s something I can do in 15 minutes, I do it in 15 minutes. If it’s something that needs three hours straight, I’ll do that. I don’t interrupt it just because I think it’s time for downtime.

But I do build in downtime every day. I do make sure that there are periods of the day where my smartphone is turned off and in a drawer. I take walks. I go out to dinner. When I do those things, I don’t take my smartphone with me. So, I think that balancing downtime with consciously productive time … I’m using the word “consciously,” because I think that in downtime we can be productive, too, but it’s at an unconscious level.

I think that we have to consciously unplug from the grid at certain times of the day. It requires a conscious effort, because if you just leave your smartphone on all the time, and you leave it near you … I’m using the smartphone as sort of the small piece of the bigger wired world, representing the whole plugged-in world.

Roger Dooley: That’s right. There are other devices that can deliver interruptions as well.

Alan Lightman: There are other devices that can interrupt us just like the smartphone can, so I’m just using that as … What is it called? Synecdoche? Whatever it is. The piece that represents the whole. The easiest path, the path of least resistance, is just to leave it turned on all the time and leave it near you.

Sociologist Jean Tenge, who just wrote the book iGen about the generation younger than the millennials, said that most young people sleep with their smartphones either on their chests or on their bedside tables. They don’t want to be more than five feet away from their smartphones. The easiest path of resistance is just to keep your smartphone turned on all the time and keep it near you. So, it takes a conscious decision to turn it off.

Roger Dooley: I’m sure you’ve seen that research, too, showing that the mere presence of a smartphone is a distraction and can affect either stress levels or problem-solving ability. Even if it’s turned off, that’s true. The best thing would be to turn off and have it in another room entirely. That seems to be the optimal condition.

Alan Lightman: I agree.

Roger Dooley: Most people don’t do that.

Alan Lightman: I turn mine off, and put it in a drawer, and close the drawer.

Roger Dooley: Do you have any other tips? We’ve talked about the need for a quiet time, for disconnecting from devices that interrupt you. Any other tips for people who want to think more effectively?

Alan Lightman: This may be an individual matter; but, for me, being out in nature rejuvenates me. Of course, it depends a little bit on where in the country you live and what time of year.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. Minnesota in February may not be the best place to appreciate nature.

Alan Lightman: No, you may not even want to be near a cold place.

Roger Dooley: Although, actually, sitting inside and looking out at the snow can be quite nice.

Alan Lightman: That can be nice. I think, for me, being with nature is very rejuvenating. If it’s possible to arrange your day so that every day that you get to spend some time outside, where you’re not trying to accomplish anything. You’ve left your to-do list in the house. You’ve left your smartphone in the house. You could be taking a walk, or you could just be sitting on a rock quietly. I think this is very healthy. I think that people who are able to build this into their week will be amazed by how much it calms them and how much it actually enhances their productivity and their creativity.

Roger Dooley: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, there’s really a ton of research, too, showing the effects of being out in nature. I guess I had one tip of my own, if you want a little bit of extra motivation to do that: A dog is a great incentive, because if you’re in the midst of working on something or answering a bunch of email, you may just say, “Well, I was going to go for a walk, but I don’t think I will.” But if your little friend is there, saying, “Hey, it’s time for our walk,” I’m going to be more likely to accomplish that. Plus, as our previous guest Paul Zak has pointed out, when you snuggle with your dog, both of you see a burst of oxytocin, too, which is always a good thing.

Alan Lightman: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah.

Roger Dooley: Let me remind our audience that we are speaking with Alan Lightman, author of Einstein’s Dreams and the new book, In Praise of Wasting Time. Alan, where can people find you online?

Alan Lightman: Well, if you google me, there’s a Wikipedia site. I have a Wikipedia site. I also have a site at M.I.T., which would come up near the first two or three entries with the Google. I do not have a Twitter account. I do not have an Instagram account.

Roger Dooley: Well, those would be kind of inconsistent with your philosophy.

Alan Lightman: I’m definitely afraid of those vehicles. I do have an author’s Facebook account. It’s different from a normal Facebook account. It’s something that my publicist at Random House asked me to get about 10 years ago.

Roger Dooley: Great.

Alan Lightman: It’s sort of a passive Facebook account that way.

Roger Dooley: Okay. Well, we will link to all of those places, to Alan’s books, and to any other resources we mentioned on the Show Notes page at rogerdooley.com/podcast, and there will be a text version of our conversation there, too, in PDF format.

Alan, thanks for being on the show.

Alan Lightman: Well, thank you, Roger. It’s delightful to be on your show. From all of the comments that you made, it sounds like you’ve had a lot of similar thoughts.

Roger Dooley: Yeah. I’m engaged in the battle that you describe, and I am probably not waging war as successfully as you have so far. But I keep trying. Anyway, thanks for being on the show, Alan. Take care.

Alan Lightman: Thank you, Roger.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of The Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at rogerdooley.com.