Dr. Nick Morgan is one of the country’s top communication speakers, theorists, and coaches. He has written speeches for Fortune 50 CEOs and presidents, as well as coached people to give Congressional testimony, to appear in the media, and to deliver unforgettable TED talks. The author of Give Your Speech, Change the World, Power Cues, and Trust Me, Nick has also written hundreds of articles for local and national publications.

Dr. Nick Morgan is one of the country’s top communication speakers, theorists, and coaches. He has written speeches for Fortune 50 CEOs and presidents, as well as coached people to give Congressional testimony, to appear in the media, and to deliver unforgettable TED talks. The author of Give Your Speech, Change the World, Power Cues, and Trust Me, Nick has also written hundreds of articles for local and national publications.

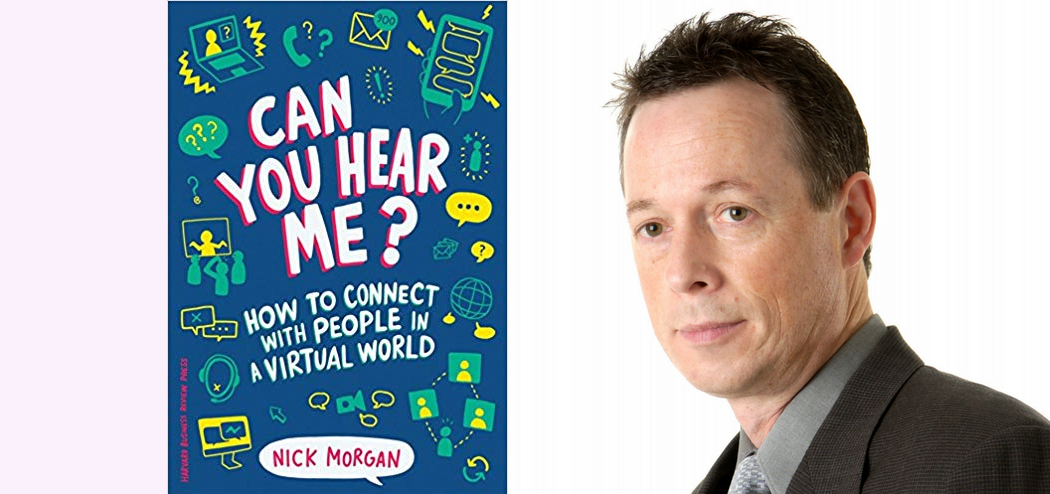

In this episode, he shares insights from his newest book, Can You Hear Me?: How to Connect with People in a Virtual World. Listen in to hear which important cues we lose when communicating virtually, why even typically kind people can easily become online trolls, and what we can do to remain sensitive to emotion in the world of online communication.

Learn how virtual communication changes our perception with @DrNickMorgan, author of CAN YOU HEAR ME?. #communication #virtual #undertones Share on X

If you enjoy the show, please drop by iTunes and leave a review while you are feeling the love! Reviews help others discover this podcast and I greatly appreciate them!

Listen in:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On Today’s Episode We’ll Learn:

- How virtual communication confuses and exhausts our brains.

- The problem with the way earbuds and speakers condense voices.

- What makes criticism seem harsher via virtual communication.

- Why Nick suggests using emojis.

- How virtual communication decreases empathy.

- What we can do to sensitize ourselves to emotion online.

- Why people tend to speak louder than necessary on video calls.

- What gives our voices a unique vocal fingerprint.

- How undertones convey leadership.

- What to do with your voice in order to sound more authoritative.

- Key questions leaders need to ask to gauge their teams’ emotional state.

Key Resources for Nick Morgan:

-

- Connect with Nick Morgan: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter | Facebook

- Amazon: Can You Hear Me?

- Kindle: Can You Hear Me?

- Amazon: Power Cues

Share the Love:

If you like The Brainfluence Podcast…

- Never miss an episode by subscribing via iTunes, Stitcher or by RSS

- Help improve the show by leaving a Rating & Review in iTunes (Here’s How)

- Join the discussion for this episode in the comments section below

Full Episode Transcript:

Welcome to Brainfluence Podcast with Roger Dooley. Author, speaker, and educator on neural marketing and the psychology of persuasion. Every week we talk with thought leaders that will help you improve your influence with factual evidence and concrete research. Introducing your host, Roger Dooley.

Roger Dooley: Welcome to the Brainfluence Podcast, I’m Roger Dooley. Our guest this week was one of our very first guests four years ago, and I’m super excited to welcome back Nick Morgan. Nick is one of America’s top communication speakers, theorists, and coaches. He’s written speeches for Fortune 50 CEOs and Presidents. He’s coached people to give congressional testimony, he’s taught others how to deliver really amazing TED talks. He’s the author of Give Your Speech, Change The World, Power Cues and Trust Me, and his new book is Can You Hear Me? How to Connect with People in a Virtual World. Welcome back, Nick.

Nick Morgan: Thanks, Roger. It’s just really great to be back again after four years.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, you know Nick, you’ve done so much with how to communicate in person. Was it a big leap to delve into how to communicate virtually?

Nick Morgan: Well, it was a real shock. I think what happens to most of us in the business world, and my experience is very typical, is that we can’t run a modern business these days without using virtual technology to communicate. We communicate over the phone, we write each other emails, we use video conferencing, we’re on audio conferences all the time. We’re just very used to that background of virtual technology. And what I’ve found as I delved into the research was that it’s much worse than we thought.

I mean I was aware of the sort of ordinary irritation of a dropped call, or technology that doesn’t quite work the way it’s supposed to. But what I found was much more alarming than that. It turns out in some very important emotional ways, virtual technology doesn’t work as well as we think it does. And so that’s really opened my eyes doing the research for the book, with what we’re dealing with here in the modern era.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well you know I think obviously digital communications are a great time saver, you know you can reach anybody on the planet. Almost for free or even for free. You can be a synchronist so if need to communicate with somebody in Australia, you don’t have to try and find sort of a mutually inconvenient time to talk, but definitely you lose so much in the process. And one of the things you highlight early on, Nick, are conference calls which in my experience are the worst. Where you know there is somebody who has organized the quarterly update conference call, and there’s a bunch of virtual participants scattered around the country and so on. Everybody’s on mute doing other stuff, sort of barely paying attention except for maybe one guy who forgot to turn mute on and you can hear him typing away and answering emails or something. Well, what’s wrong with the conference calls?

Nick Morgan: well the first thing is, and this is a great way to jump into it, is the lack of feedback. And by that I mean, we humans are used to getting many kinds of feedback all the time to our unconscious minds. So, we see, we smell, we taste, we hear, we touch. The five senses that we’re used to. Everything around us all the time, and we’re constantly getting information and then there’s a sixth sense and at least several more of, the neuro scientists love to talk about, that also feed us information. And one of my favorite ones is that sixth sense, that proprioception, which is how humans track where we are in space, and where other people are in space.

And so for example, if you’re at a cocktail party, believe it or not you’re unconscious mind is working overtime to keep track of where you are in space, and where all the other people milling around in that cocktail party are in space. Now, when you get on an audio conference, your brain still craves that information but it gets none of it. And as a result, and here’s where it gets interesting, it makes up information to fill those empty channels of feedback that it’s used to getting. And because the brain’s job is to keep us alive, it tends to fill those empty channels with negative information that it makes up. In other words, it perceives danger where there may not be any real danger, because it’s better to err on the side of caution in order to keep us alive.

So as a result, we get paranoid when we’re talking on an audio conference. We imagine that the other people aren’t listening because they don’t like us, or they don’t like the point we’re making, and it’s that lack of feedback-

Roger Dooley: In many cases you’d be right.

Nick Morgan: And all too often, we’re right, exactly. And so, that’s where audio conferences begin. They begin in this desperate state of this lack of information that’s coming into us, and that causes us to go a little bit crazy on audio conferences.

Roger Dooley: Is the spatial information or lack thereof why we yell at each other when we’re talking to somebody far away.

Nick Morgan: That’s right, and what’s funny about this for me is it happens on video conferences, too, and again that’s because that sense of spatial information isn’t entirely visual, it is to a certain extent to do with the atmosphere around us. So if you’ve ever had that feeling of that sort of creepy crawly sense on the back of your neck and you turn around and somebody’s looking to you, that’s a little bit of that sense going on. Where it’s actually some physical data as well as the visual data. We feel a little bit of air moving perhaps. That’s very subtle but as a result, when we’re on a video conference and certainly when we’re on an audio conference, we think people are further away than they actually are because we’re not getting that sensory data. And so we, as you know, we end up shouting at each other.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I think probably there’s one element too, that is the volume of the person you’re talking to. You know I think that our brains think, that if we have difficulty hearing the other person, then they clearly are having difficulty hearing us. So that, like in the real world, if you were at both ends of a long room, if you had difficulty hearing the other person, you’d just know that, “Well, they’re far away, so I have to talk louder.” But, these days we all have volume controls, so you know the volume might be down, and then the person would seem low in volume and you tend to yell back at them, even though they can hear you just fine, even if you talk in a normal tone of voice.

Nick Morgan: Well one of the interesting things about that, about phone conversations is that the sound is condensed. We don’t get the high frequencies that we do get in person. So, we have this extraordinary range, most of us. I mean obviously there’s some deafness that sets in as you begin to get older, but when we’re young we can hear something like 20 hertz or cycles per second sound to 20,000 hertz. Twenty thousand hertz is a very high sound. It’s the sort of buzzing as of insects, it’s that kind of sound. And so it’s not really necessary per se to hear those sounds in order to understand speech, but it does fill in a little bit and make it easier to pick the sounds out, of say a crowded room.

And so one of the things that happens on a phone call is, most of those upper frequencies and a lot of the lower ones are taken away, and as a result, it is harder to hear even if the volume is loud. It’s a little bit like that deafness that tends to set in when somebody gets over 65, where they start to lose the upper end of the frequencies so they have a hard time hearing what somebody is saying in a room where there’s a lot of background noise. So, it’s sort of an early experience of deafness for us to speak on an audio conference.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, I’m curious. I understand that the original telephone system, back when it was an analog system worked in limited frequencies. Now that we’re in this digital space, how true is that still? In other words, we’re chatting via Skype. Are we also losing some of those high frequencies?

Nick Morgan: We are. There was never a good time to suddenly expand the bandwidth of sound. Engineers created this compressed signal and they’ve always been trying to add lots of other things into our technology, in terms of bandwidth. So, we wanted video, we want to be able to stream music and movies and things like that. So there was never a good time to add a lot of sound back in. Now that said, there are some technologies that are creating better sound, so been working with a couple of video conferencing companies that are trying to put HD sound back in. And so that will slowly happen as our bandwidth gets greater and greater. But on the average phone call, the average computer headset, the sound is very condensed and therefore very poor.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, interesting. And also might give on a partially, like in this conversation, I’m recording with a more or less studio quality mic, so presumably I’m getting pretty wide frequency range, but your signal’s being transmitted via Skype. So, probably there are technical solutions for that, by recording on both ends with good equipment and then combining the two. That might be something that we have to explore in the future, because this is how we usually do it, but we might be missing something. I’m curious, Nick in your earlier book, Power Cues, you talked about undertones and overtones. Can you explain a little bit about that, because I thought that was a really fascinating topic? And of course, that’s what you’re just referring to here, is some of this information that we’re losing in digital communications or digitized communications.

Nick Morgan: Right, and as you pointed out, you can speak on or perhaps record into a very high quality studio mic, but of course think about your audience. Are they listening on earbuds? Earbuds are the single worst abomination foisted on human beings who care about sound in the 21st century, because they use a trick of sound to try to create a sense of the lower frequencies and that is they get your ear to substitute for the sound that isn’t there. Your ear is putting back in, imagining what those sounds are like. Even the lower sounds that don’t actually show up on an earbud. So, earbuds are terrible and that’s a big part of the problem as to why sound is so bad these days.

But back to your question about overtones and undertones, so the way to think about this is the extraordinary ability that humans have to detect other people’s voices with no conscious effort. So we all know several hundred voices when you think about it. We know the voices of our loved ones, of our friends, of our colleagues, of a bunch of famous people and politicians. And we can identify those voices in an instant, without having to think about it. And the way we do that is absolutely extraordinary. So, I’m speaking now at a pitch, and if I were to elongate one of the vowels, we could match that pitch on the piano. So if I started saying piano, and I’d Oh, I held that note, we could go find that on the piano, it would be a certain pitch. Let’s say, G below middle C.

But that isn’t the only note that’s being represented as I speak. The reason my voice has a unique sound, just as your voice has a unique sound, just as everybody’s voice is unique, is that with each of those basic pitches come a whole series of overtones and undertones that make up my unique vocal fingerprint if you will. Just as you have a unique vocal fingerprint and so does President Obama. All right, so the issue with condensing then the sounds is that when you condense the signal so that you cut out a number of the overtones and undertones, then of course voices lose their distinctiveness. So, at the first level, they get a little less interesting and a little harder to sort of tell apart, one from another. So they get more bland sounding.

But there’s a further piece that’s even more important which is that the emotions in a human voice are conveyed in the undertones. So when you condense those undertones and remove them, or mute them, or kind of limit them, then less emotion is carried in the voice. Which means, I have to work much, much harder on a phone in order to convey the excitement I feel talking about this information, Roger. I have to yell or I have to work really hard to convey the same amount of emotion that perhaps might be conveyed in a normal conversation with all the other body language and so on, and vocal tones that are easily being conveyed.

And there’s a further implication for this, which is even more fascinating, which is that not only emotions are conveyed in those undertones, but also leadership. And so it turns out that when we’re sitting in a room for example, let’s say a business work team that’s been meeting for several weeks to get a job done. It turns out that whoever’s leading that group, that is the real leader, not necessarily the leader with the title. But, the real leader, the intellectual leader or the emotional leader of the team. When he or she speaks, those undertones are picked up by the other people in the room and matched, and so we literally get on the same wavelength with people as a way of showing that we understand or we acknowledge their leadership. And so, when you take that out of the equation, that’s why audio conferences, that’s another reason why audio conferences get so uninspiring and so boring, and actually hard to make good decisions on, because you’re taking out most of the ways in which humans care about one another, and care to make decisions.

Roger Dooley: I don’t want to go too far down that rabbit hole, but can we control those undertones if we want to project leadership?

Nick Morgan: Yes you can. The way to think about it is, is to think about what happens to your voice when you are frightened or scared, and so I always use the example and this just happened again in New York City. I was there the other day and somebody walking in front of me was walking with the head down in the cell phone, and nearly walked into an oncoming car. And fortunately, before I could shout, somebody behind me said, “Watch out.” And so when you’re panicked, when the human voice is panicked, the voice goes up. Goes to the higher end of the range, and so that conveys excitement, passion, panic, fear, but it doesn’t convey authority.

Authority is conveyed at the lower end of our register, so if I want to sound like I’m in charge of this conversation, Roger, then I need to project my voice lower down on my particular scale. And so everybody’s voice is a little different from one another. We have different pitches, a pitch range, the lowest note we can comfortably sing or match, the highest note we can comfortably sing or match. And so we wanna be down at the quarter end of our range, to sound the most authoritative.

Roger Dooley: Interesting. Well, we’ll remember that for in person conversations. But there may-

Nick Morgan: You can do a little bit of it on an audio conference. I don’t mean to suggest it’s completely eliminated. It is for the people listening on earbuds. But for the rest of us who are listening on reasonable quality microphones, we’re still picking up a little bit of that, just not as much as we need for it to really be a proper conversation.

Roger Dooley: So, Nick, in Can You Hear Me, you identify five big problems. Why don’t I just quickly enumerate those. I’m sure I won’t have time to go through them all, but what are the five big problems of virtual communication?

Nick Morgan: Sure, the first one as I said is a lack of feedback. You’re just not getting the kinds of information that the human being is wired, hard wired to get and appreciate. The sights, the smells, and the sounds. They’re all limited in various ways. Obviously with the video conference you get a little bit more, but you’re still not getting some of those kinds of sensory information I talked about in person. So, that’s the first one. The second one then is, because we get very little information like this, we lack empathy. It’s those kinds of subtle bits of information that come across to us and are picked up by our unconscious mind, the sensory information, that lets us know how the other person is feeling.

And so, we’ve all had the experience, or many of us had the experience of being trolled online. Somebody really criticizes us harshly. Often you find when you meet somebody who turns out to be really nasty online, is they’re much more understanding and human in person. And so there’s something nasty that happens to us in the case of trolling when we get online, and that’s because of that lack of that empathy. You take away the human emotional information that’s being shared naturally through the sensory information, and people get less empathetic and so they become trolls.

Roger Dooley: I can definitely verify that, Nick, because I managed online communities for years, and it was really amazing how very reasonable, smart, sensitive, intelligent people could get so messed up online where they’re at each other’s throats, arguing about pointless stuff. Where, I’m sure if you met anyone of them in person, they would be wonderful people, and even their behavior elsewhere in other conversations was very helpful to other people. So they weren’t horrible people themselves, but somehow they could get set off by something somebody else said and before you knew it, there was a huge fight going on.

Nick Morgan: Yeah, you put them online and something goes crazy, and it’s that lack of normal emotional information. It’s like cutting them loose and some people just go crazy with that problem. The third one then, derives from that to an extent is the lack of control you have over the digital information about you. Your persona, the digital footprint you leave behind. And many people have found embarrassing photos from wild college parties that show up when they’re trying to get a job.

Roger Dooley: Thank goodness there was no internet in my college days.

Nick Morgan: Exactly, right. It’s such good news for those of us who came along before the internet came. So, more than that, there’s just an enormous amount of information about everybody and not all of its accurate, of course. Especially if you have a name like mine, Nick Morgan. There are millions of Nick Morgans out there and as a result, information can get scrambled and it can get posted about you that doesn’t have anything to do with you at all. In the real world, when we hear things about people, we know it’s gossip perhaps, or we meet the person and they deny it strenuously, and so we can move on. But in the digital world, it’s there forever, essentially.

The fourth problem then is the difficulty in making good decisions online and the reason for that goes back to the earlier two, that is once you take out the information about emotion, then we have a hard time judging how important things are. Because the emotional subtext is what tells us, this is a really big decision, or this is just a little one. This matters or this doesn’t matter. And this gets you back to the trolling a little bit, because we’re a bit unmoored without that emotional information and we tend to go a bit nuts. But, as a result, we have a hard time making good decisions, and so the lack of emotion leads to poor decision making.

And then the final problem is the lack of just fundamental human connection and therefore commitment. And one of the things that you find with your online connections, is they’re much more brittle, they’re much more fragile. And in a sense, we take that as just the natural part of online commerce, let’s say. If the website doesn’t deliver on the product that we’ve ordered. We never go back to that website and try it again. And that’s why something like Amazon works so very hard to have brilliant customer service, and to be so reliable, is because they know, living in the online world, how fragile it is. In the real world, we’re much more forgiving, because we get to know the person in a deeper sense and so, if they fail to deliver one time, we’ll accept their apology. But in the online world, that connection is much more fragile, and that’s the final, final problem.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, so given this lack of ability to detect other people’s emotions via those conventional means that we use, the nonconscious cues and maybe all of the tonal range of our voice and so on, are there some things that we can do to sort of sensitize ourselves to those emotions, to pick up whatever information we can, going from whatever they’re doing or saying?

Nick Morgan: Yes, there are, and it’s at the moment, it’s not as good, let’s just be honest about it, as the face to face connections. Especially and I’m talking mostly in the book, is mostly aimed at business teams that, say meet regularly and have a leader, and say they’re positioned in various places around the world. They have a team in Singapore, and a team in California, and a team in France, let’s say. And so they have regular online meetings and misunderstandings arise and they try to sort them out. That kind of arrangement. There are ways you can make that better, but it’s simply not as good as a face to face meeting.

So with that caveat, one of the things I recommend for example, is starting to add more emotional language back into your conversation. And so with a team like that, you need to start to train the team, as to begin tell each other how they feel, and how they feel about what has just been said. And so one of the key questions that a team leader, for example, needs to start to learn to ask is, “How does what I just said make you feel?” Because you don’t know in the online world, and if you’re trying to have a team work together and avoid misunderstandings and that kind of thing, if you don’t ask that question, it will normally get answered by silence, and you’re gonna assume therefore that it’s okay. But that’s how those kind of misunderstandings arise.

And so I give another example of a very simple thing you can do at the beginning of an audio conference team meeting, and at the end again, which is to say, go around and get everybody to give a temperature check. You can do it as simple as the colors of a stoplight. So, red means, “I’m having a terrible day, don’t bother me.” Yellow means, “I’m hanging in there, it’s not great but it’s okay,” and green means, “Everything’s good.” And so if you ask people that, it’s a fairly safe way for them to just check in and say how they are, and then if you ask them again at the end of the meeting, then you get a sense of what’s happened during the meeting and whether things have gotten worse or better for them. It also gives you an opportunity to follow up if somebody says, “Today I’m flashing red,” then you might wanna say, “Well, let’s follow up offline, and find out what’s going on. Maybe we can make it better.”

So we need to, we need to consciously put the language of emotion and human connection back in, because it’s been stripped out essentially of these virtual connections. And that’s really what the book’s about. I have many examples of ways to do that, but those are sort of the basic ideas. It’s starting to get conscious about the emotional connection and tending to it, paying attention to it, and asking people, “How are you? How did that conversation make you feel?” And it you don’t ask directly, as I say, all too often online people will just tune out, and they won’t bother. And that’s again, because that connection is not as strong. You don’t feel like you have to tend to the emotional connection in the room, because it’s not the same as a face to face meeting, where you catch the roll of the eye, or the frown, or the shake of the head. And because you don’t get that information, you have to consciously add it back in.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, something that I’ve heard works for companies that have a lot of distributed teams, or even have 100% remote workers is to selectively do in person things. Sometimes they might do any onboarding process, or anytime they bring in a new person, that’s done for say, two weeks in person in one of their locations. And the other would be to bring people together, say annually for a week or two, even though it’s expensive in terms of travel. Establishing those emotional connections in person then lubricates the wheels a little bit for those digital interactions where you don’t have that opportunity to convey all of the emotion.

Nick Morgan: Yeah, that’s exactly right. That’s something I mention in the book and say, basically as a rule, if the subject of the meeting or what’s on the table is sufficiently important, then you just have to bite the bullet and meet face to face. And I say, for example, you should never hire or fire somebody remotely. It’s just unconscionable, especially the firing part. People will probably forgive you if you hire them remotely, but to your point if you, to onboard people as they say, it’s really important that, that be done face to face so that the team has the chance to gel and learn to trust each other. Because as I say, what you can’t do well online is establish that strong human connection.

The trust is just fragile and the least little problem is gonna make it go away. But if you can as you suggest, spend a week or two together at the beginning of the relationship, then you can establish that trust easily and naturally in the way that it’s most often done with people which is unconsciously, because of face to face human interaction. Then that will stand you in good stead throughout the term of the engagement, whether it’s a team that’s just meeting and working together for a year or for longer. And so yeah, so every now and then, until we come up with some better technology, you still gotta do the face to face meetings, even though as you say costs a lot of money in terms of travel, but it’s gotta be done.

Roger Dooley: Right, well pretty soon, maybe we’ll all have holodecks or something where we can see people’s holograms in front of us, that are lifelike and convey the body language and everything else, but not quite there yet.

Nick Morgan: Not quite there yet, yes. The assisted reality or that kind of augmented reality, where you have a headset on say, and that will put you into a space and the computer can give you kinds of information that you wouldn’t normally have at your fingertips. That kind of virtual technology I think holds real promise, because it’s sort of enhancing our current reality instead of trying to substitute for it. But, we’ll see. Right now as you suggest, we just don’t have the technology to do it, any better than a face to face meeting.

Roger Dooley: Yeah, well I’m sure we’ll get there eventually. You know, criticism is probably something most of us hate to delivery and hate to receive, almost in equal measure. I know for me, it’s hard to do, hard to have somebody do it to you. Is that even tougher in virtual communication?

Nick Morgan: Much. It’s nearly impossible for the reasons, the fragility of the connection as I suggested, and it’s why criticism always or so often turns to trolling. The only way you can begin to do it is with the praise, criticism, praise sandwich, where you wrap the criticism within liberal slices of praise. But even so, I wouldn’t recommend trying to do anything like that on an ongoing basis, where the relationship in the team is important to you. Because it’s just gonna make the other person feel too attacked. Because one of the things that people are not often aware of, but when they deliver criticism to a teammate say, but they’re trying to keep the relationship going, usually what their body language does is, the body language sends out friendly messages of the continuation of the relationship, and the ongoing desire to keep the connection strong and that kind of thing.

So the words may sting a little, but you can say it in a way where the tone is softer or there’s a kindly look in your eye, or a head tilt or something like that. All of that of course vanishes in the virtual world, and it doesn’t even show up very well on video, because of the weakness of that technology still. So as a result, it’s just very hard to do effectively and even harder for people to accept, to your point. We really don’t like getting criticized virtually.

Roger Dooley: Yep, you know that brings me to the next point I was gonna ask you about, Nick, and that is video. We can agree that various types of conference calls and what not, where there’s no video, or only the main speaker is on video, are really very lacking in communication bandwidth, but if you do have to have a conversation with an individual, how good or how bad is a one on one video. Say, we wanna have a conversation now, and we both flipped on video so we could see each other’s faces or maybe torsos. You know, how effective is that or do you still run into a lot of problems that way?

Nick Morgan: It’s interesting. Two things happen to most people on video that you wouldn’t think would happen, and that tells you something about the kind of connection. And so the first thing is, people end up shouting at each other, usually by the end of the call. And that goes back to the inability to measure accurately the distance between them, as we talked a little bit about earlier. So the brain goes into hyperdrive, trying to figure out how far away is that person, and as a result that information is lacking and so, you make it up by thinking, “Oh, he must be further away than I realized,” and so you end up shouting.

Roger Dooley: Well especially I suppose if there’s artifacts in the video, because video isn’t always perfect. With today’s internet speeds, you know you get little glitches in there where somebody freezes for half a second, or gets pixelated for a couple of seconds, and I’m sure your brain is interpreting that as, “Okay, this person is not very close to me.”

Nick Morgan: Exactly, and the other thing to remember too, is that video, at least so far is two dimensional. And so what you’re doing there, you’re making your brain turn two dimensions into three, and to try to make guesses about how far away that person is, or where they’re situated in space. And so it’s more work for the brain, which leads to the second problem, which is, it simply is fatiguing and that’s the other thing that’s sort of surprising. You wouldn’t think having a video conference would be all that tiring, but the difference between, trust me I’ve tried this many times and talked about it with a number of clients, a four hour video conference and a four hour meeting is astounding. At the end of the four hour video conference, you’re ready to become a hermit and disengage from humanity for a week’s rest. Four hour personal meeting can be quite invigorating and fun if the topic is entertaining and you like the other person.

But I’ve never heard anybody say, after a four hour video conference, “That was great. Let’s do four more.” And the reason is because your brain is working so hard, the unconscious mind is working so hard to fill in the information that’s not coming to it naturally. That it just gets exhausted after a while. It’s like your brain is saying, “How far away, how far away?” Constantly and not getting an answer, and it finally just gives up, and so that’s very fatiguing for the brain. And trying to turn, as I say, two dimensions into three, so it’s not quite there yet, as you say, at some point maybe we’ll all be holograms or on holodecks, and then it will all seem easier. It’ll make sense to us, because the early signs with that kind of augmented reality are very promising. It has a real feel to us that feels very lifelike. So stay tuned, it’ll get better. But right now-

Roger Dooley: Right, we could all put on our Oculus Rift headsets and sit around a virtual conference table looking at each other. We’ll get there. One last question, Nick. What about emojis?

Nick Morgan: Now emojis are interesting. So, when I first started doing the research for the book, I came across research that suggested that you shouldn’t use emojis because they don’t seem professional. So it will damage you in your professional career. Let’s say you’re a rising high potential leader, and if you’re the kind that puts a lot of emojis into your communications, your text messages, let’s say, and your colleagues see this, then they’re gonna think that you’re just a high schooler or something. The research was suggesting don’t do it. I think that’s gonna change, and I recommend very highly to people to use emojis. I think we need to use more emojis because what emojis can do is they can tell us that comment, which in the past in an email would have led to a misunderstanding which take another six emails to try to straighten out. Where you made what you thought was a brilliant joke in the email, and somehow the other person didn’t get that brilliant joke and thought you were insulting them.

And everybody I’ve talked to about this has had that kind of experience where they’ve been misunderstood in an email, and the other person just inexplicably took the email to mean something insulting or rude, or careless.

Roger Dooley: Absolutely. I have a kind of sarcastic sense of humor, Nick, and that can really go wrong in digital communications.

Nick Morgan: Yes, and so the emoji is a very crude and sort of simple minded way of putting back in the wink, the smile, the nod, to say, “I didn’t really mean that.” Now, unfortunately one of the forms that takes is back to trolling. People can say mean things, and then they’ll put a smiley emoticon to say, “I really didn’t mean that,” when in fact they did. So people lie with emoticons, but then they lie face to face too, so that’s a risk in human communications generally. But on the whole, I would recommend to people, get used to emoticons. We’re gonna be seeing more and more of them. In another five or six years, they will be all around us all the time in an effort to try to put the emotions back in that are missing.

Roger Dooley: Great well, and now we all have permission to use more emojis. So let me remind our listeners, we’re speaking with Nick Morgan, all around communications expert and author of the new book, Can You Hear Me? How to Connect with People in a Virtual World. How can people find you, Nick?

Nick Morgan: Go to our website, publicwords.com. There’s contact forms, lots of ways to get in touch with us, and lots of information about the book, and many other things to do with public speaking and communications. And I’m also on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn as Dr. Nick Morgan, so @DrNickMorgan, you’ll find me in virtually all those forums.

Roger Dooley: Great, well we will link to all of those places, to Nick’s new book, and to any other resources we talked about on the show notes page at rogerDooley.com/podcast. And even though it won’t have the undertones or overtones, we’ll have a text version of our conversation there, too. Nick, thanks for being on the show. Great to have you back.

Nick Morgan: Roger, it was great to be back with you after a number of years. I should write more books and I get to be on your show more often. Thank you.

Roger Dooley: We won’t wait for the next book, Nick. We’ll do it before then.

Nick Morgan: Excellent.

Roger Dooley: Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Brainfluence Podcast. To continue the discussion and to find your own path to brainy success, please visit us at rogerDooley.com.